Signalment:

Gross Description:

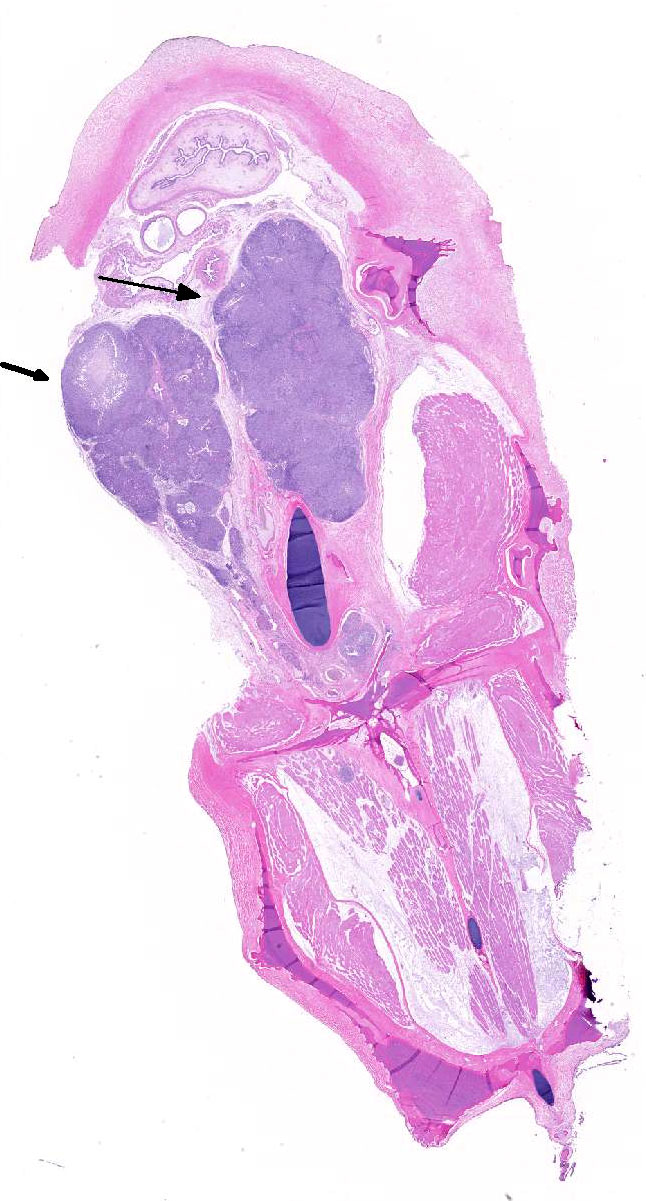

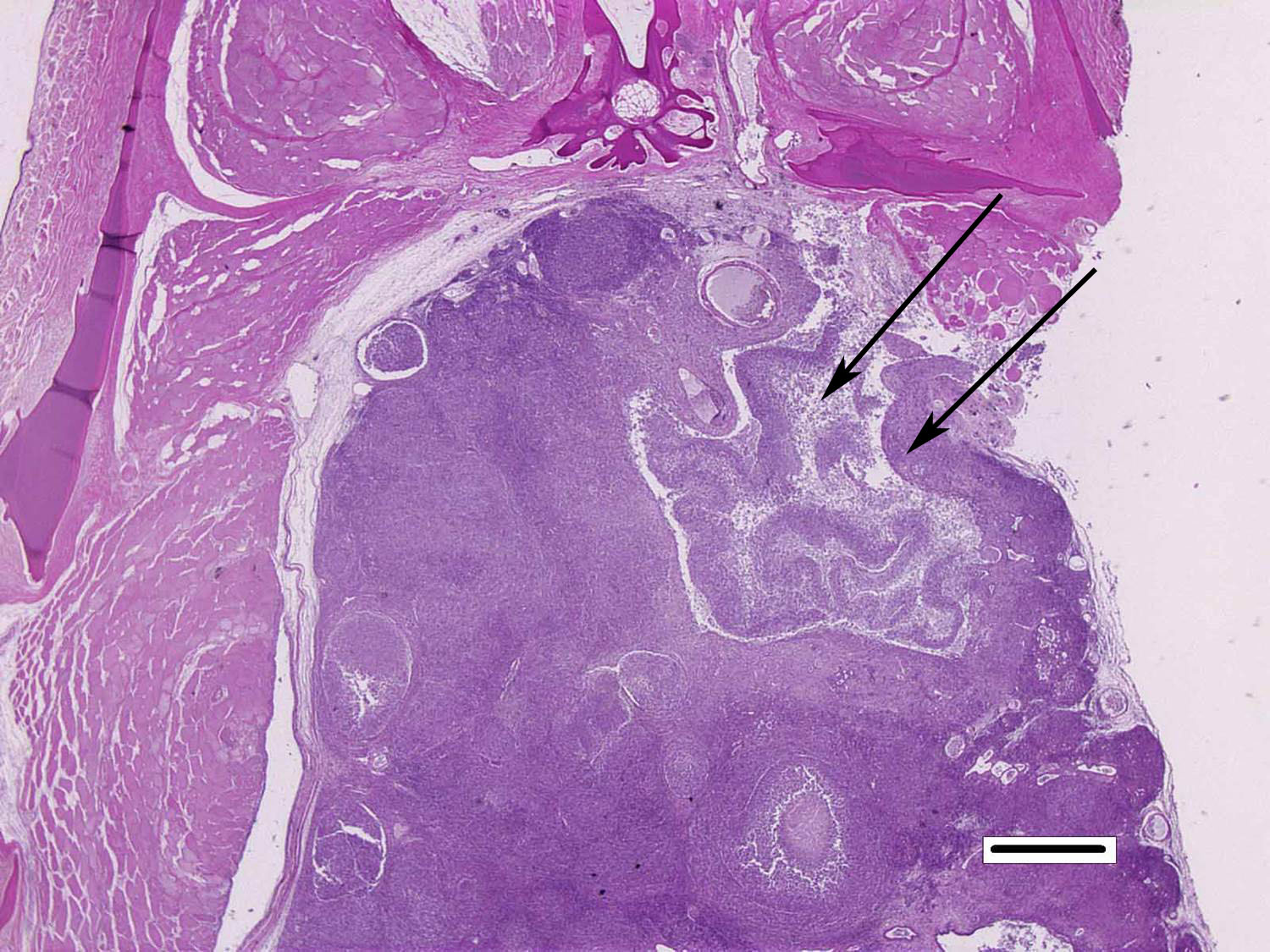

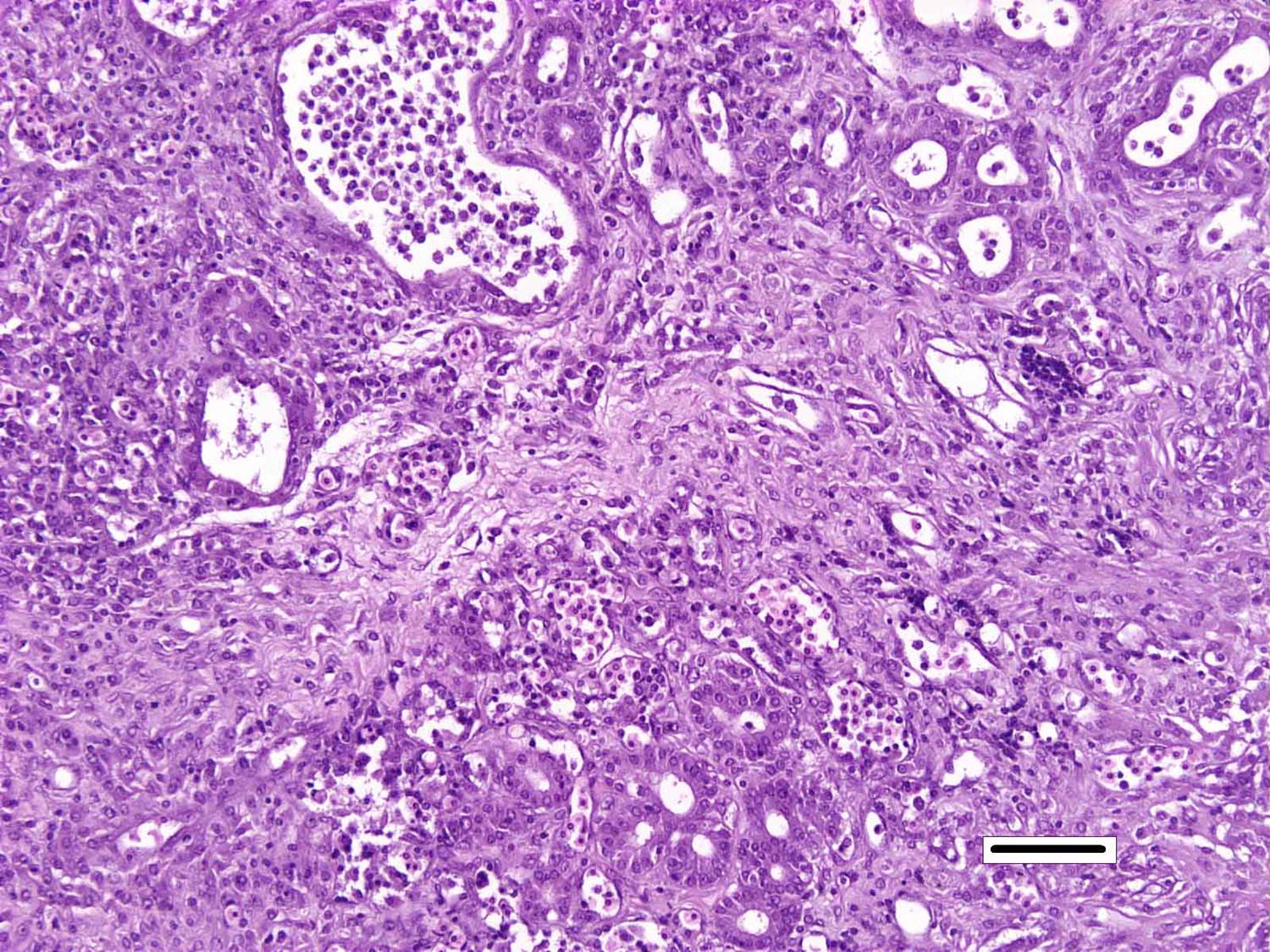

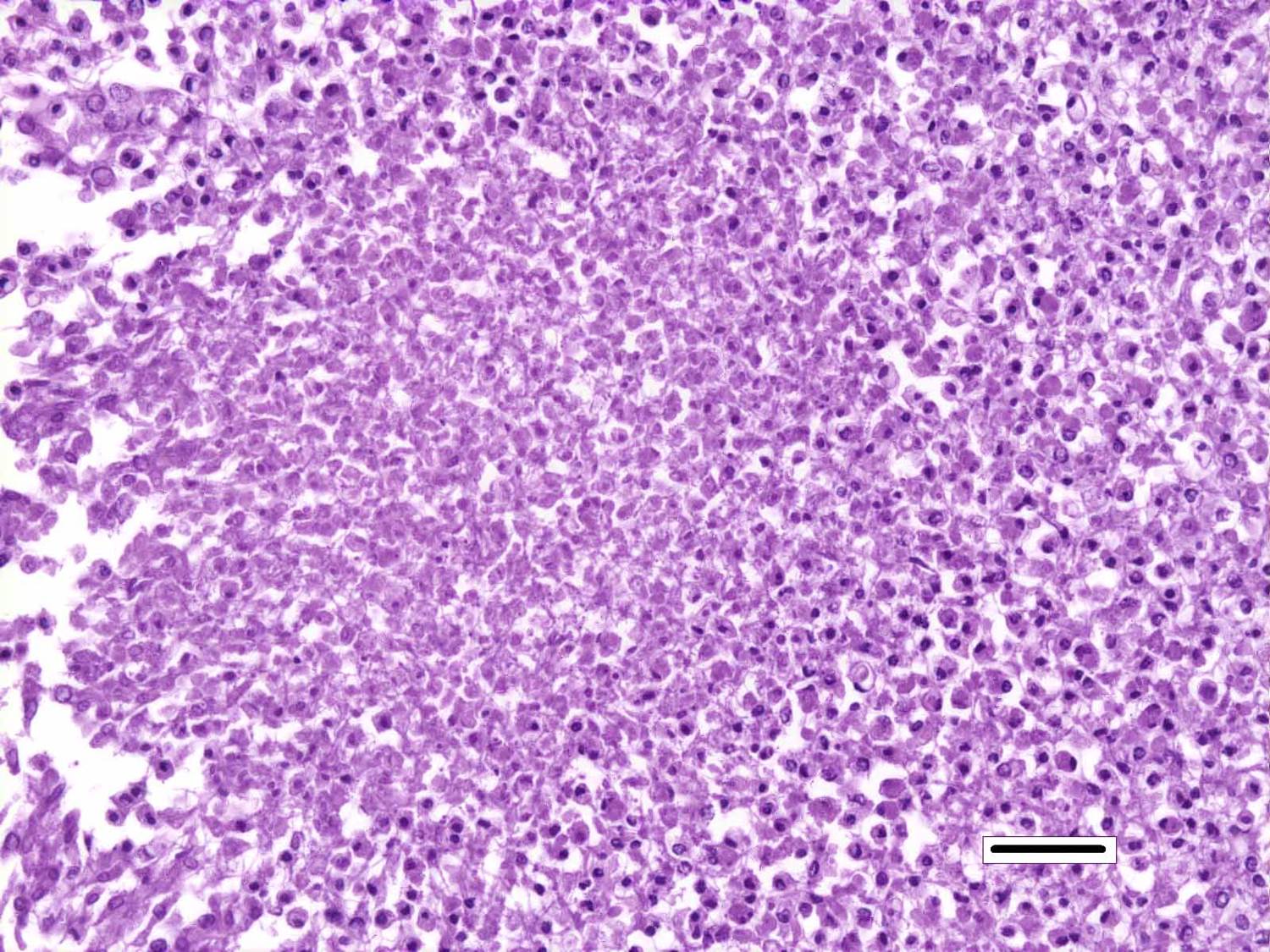

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

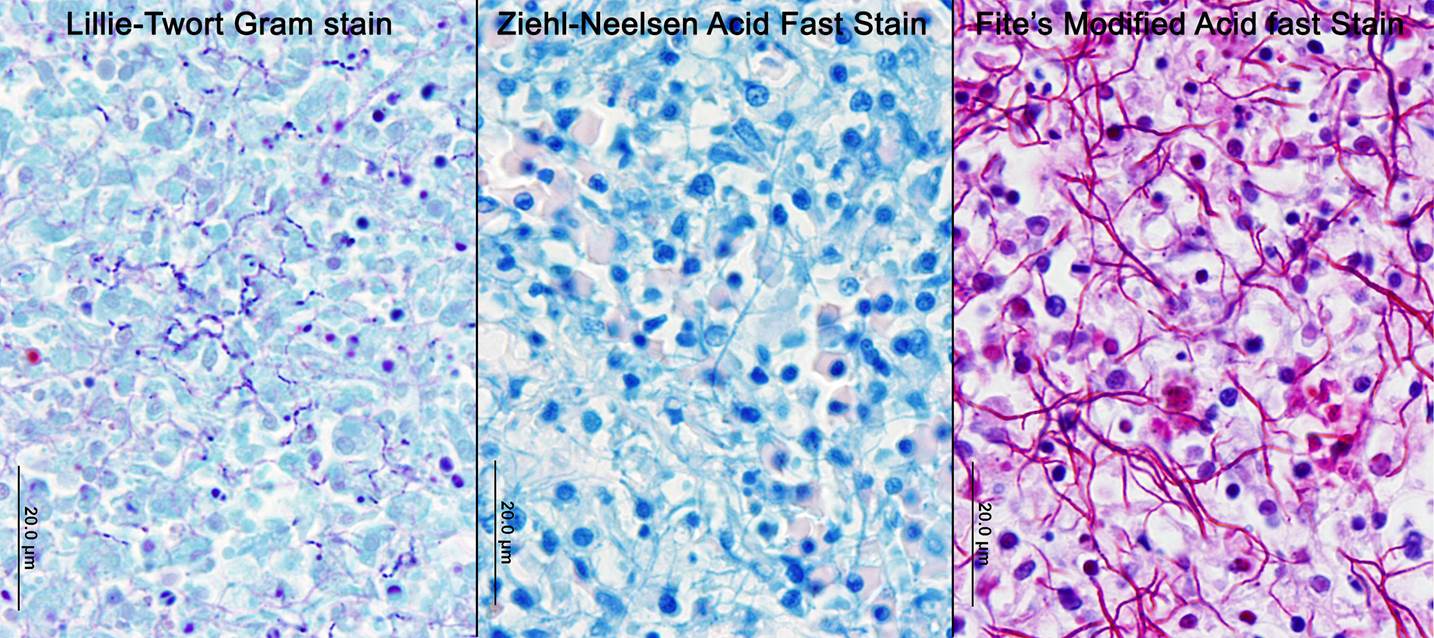

Nocardiosis in fish has been summarized in multiple sources.3,7 Nocardia asteroides was first reported from neon tetra in 1962 and has caused epizootics primarily in freshwater fish. N. seriolae is a major pathogen of marine fish worldwide, particularly in Asian mariculture.2,9 Nocardia salmonicida has received little attention since its first isolation from sockeye salmon.1 The systemic granulomatous disease is characterized by progressive lethargy and emaciation. Infections can be confused both clinically and grossly with those of mycobacteriosis, which is extremely common in captive seahorses. Gross lesions can include skin ulcers, muscle necrosis, and organomegaly, with small nodules in parenchymal organs and the gills. Microscopically, nodules are variously described as granulomas and abscesses, frequently with necrotic centers, peripheral macrophages, lymphocytes, possibly giant cells, and variable fibrous encapsulation.7 The filamentous branching bacteria, stain weakly and irregularly gram-positive, poorly or not at all with the Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain, and are best visualized with modified acid-fast stains, such as Fite�s.

Although contaminated feed has been suggested as a source of infection, the pathogenesis of natural disease is poorly understood. Transmission has been demonstrated experimentally by injection, dermal abrasion, immersion, feeding and cohabitation.6 Losses of 15-17% from N. seriolae have been reported in cultured sea bass and yellow croaker, respectively.2,9 While microscopic lesions are frequently described, many reports only include bacterial identification to the genus level.5 Identification of Nocardia nova in this case suggests greater species diversity of Nocardia could be involved in fish disease.1

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Although generally thought to cause low mortality in fish, Nocardia spp. can induce severe chronic granulomatous systemic disease.1,7 In this case, the normal renal architecture is almost completely effaced by multifocal to coalescing necrotizing and granulomatous inflammation. Although there is some slide variability, in several examined tissue sections, inflammation extends into the adjacent coelomic cavity and skeletal muscle. As mentioned by the contributor, the primary differential diagnosis for piscine nocardiosis includes infection with the much more common Mycobacteria sp., which produces nearly identical gross and histological lesions in fish.7 Gross lesions include cachexia, ascites, dermal ulceration, multifocal skeletal muscle necrosis, and small white well-circumscribed granulomas in the kidney, spleen, heart, and liver.7 As a result, nocardiosis can be easily misdiagnosed as mycobacteriosis. Positive differentiation requires isolation and identification of the infectious organism and examination of histologic sections of infected organs. Histologically, Mycobacteria sp. are non-filamentous, non-branching, gram-positive, strongly acid-fast bacteria and are easily differentiated from Nocardia with the special histochemical stains previously mentioned.1,7,8� Additionally, virulent Mycobacteria spp. are obligate intracellular pathogens that replicate within host macrophages. In contrast, pathogenic Nocardia spp. are facultative intracellular bacteria that have complex cell wall lipids that allow for resistance to phagocytosis by host macrophages.7,8 In this case, the vast majority of bacteria are extracellular.

In a small number of tissue sections, conference participants noted a focal granuloma within the intestinal wall centered on a degenerate larval cestode characterized by a 2 um eosinophilic tegument, a lacy, fibrillar eosinophilic parenchymatous body cavity, scattered 5 um diameter, basophilic, calcareous corpuscles, and birefringent hooks in some sections.4 The pathologic significance of the parasitic granuloma in the intestinal wall, in this case, is unclear; however, it may indicate that this seahorse was immunocompromised, allowing for the proliferation of various concurrent opportunistic pathogens.

References:

1.     Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, Wallace RJ. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006; 19:259-282.

2.     Chen SC, Lee JL, Lai JC, Gu YW, Wang CT, Chang HY, Tsai KH. Nocardiosis in sea bass, Lateolabrax japonicus, in Taiwan. J Fish Dis. 2000; 23:299-307.

3.     Cornwell ER, Cinelli MJ, McIntosh DM, Blank GS, Wooster GA, Groocock GH, Getchell RG, Bowser PR. Epizootic Nocardia infection in cultured weakfish, Cynoscion regalis (Bloch and Schneider). J Fish Dis. 2011; 34:567�571.

4.     Gardiner, CH, Poynton, SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Washington, D.C: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology, 1999:35�38.

5.     Elkesh A, Kantham KPL, Shinn AP, Crumlish M, Richards RH. Systemic nocardiosis in a Mediterranean population of cultured meagre, Argyrosomas regius Asso (Perciformes; Sciaenidae). J Fish Dis. 2013; 36:141-149.

6.     Itano T, Kawakami H, Kono T, Sakai M. Experimental induction of nocardiosis in yellowtail, Seriola quinqueradiata Temminck & Schlegel by artificial challenge. J Fish Dis. 2006; 29:529�534.

7.     Lewis S, Chinabut S. Mycobacteriosis and Nocardiosis. In: Woo PTK, Bruno DW eds, Fish Diseases and Disorders, Volume 3: Viral, Bacterial and Fungal Infections 2nd ed. CABI Publishing, Oxfordshire; 2011:397-423.

8.     Mauldin E, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer�s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier; 2016:637-638.

9.     Wang G-L, Yuan S-P, Jin S. Nocardiosis in large yellow croaker, Larimichthys crocea (Richardson). J Fish Dis. 2008; 28:339-345.