Signalment:

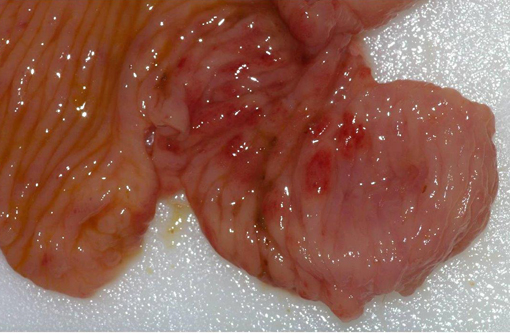

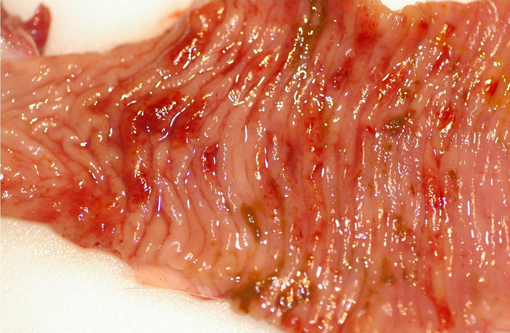

Gross Description:

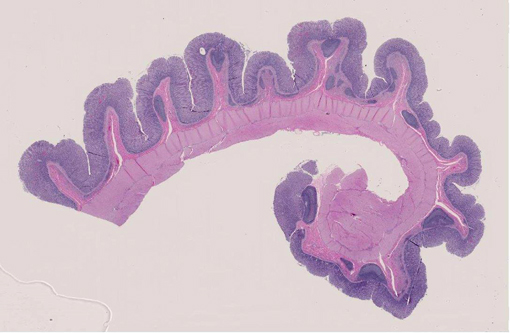

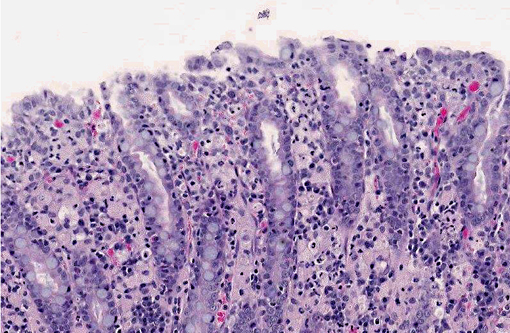

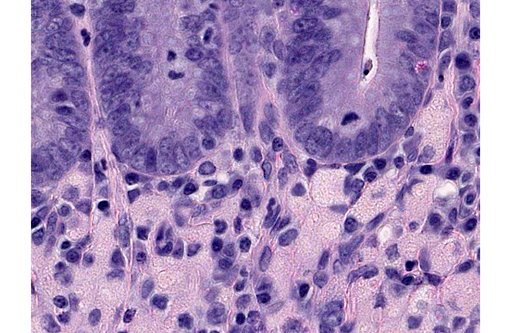

Histopathologic Description:

In the cecum (not submitted), findings are similar as described above.

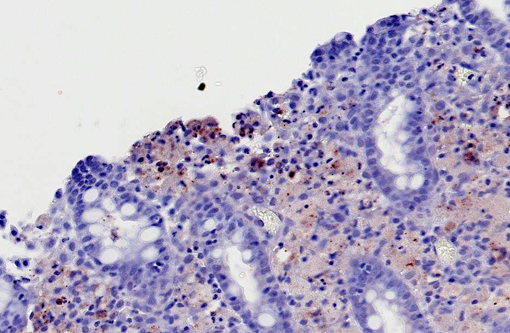

Macrophages infiltrating the colonic mucosa and submucosa are PAS-positive (data not shown). Immunohistochemical stains using polyclonal anti-Escherichia coli antibody highlighted numerous bacillary bacteria present free in the upper lamina propria and in the cytoplasm of macrophages.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Grossly, the colon of affected dogs is thickened, folded and perhaps dilated, with focal areas of scarring. On the mucosa, the lesion varies from red, frequently raised areas to patchy or coalescing ulcers. Histologically, it is characterized by a dense inflammatory infiltrate in the mucosa and submucosa, composed mainly by large numbers of foamy, PAS-positive macrophages which contain phagocytized necrotic cellular debris and bacteria. Additionally, there is distortion of the normal glandular architecture and decreased numbers of goblet cells. Ulceration, which does not progress beyond the submucosa, arises from the superficial epithelial erosion and destruction of the basement membrane.(1) Resultant clinical signs consist of large bowel diarrhea, tenesmus, hematochezia and marked weight loss.(4)

The inflammatory infiltrate of the colonic mucosa and submucosa was further characterized in an immunohistochemical study. German et al (2000) found increased IgG plasma cells, plus PAS, CD3, L1 and MHC class II positive cells in the lamina propria, in conjunction with increased enterocyte MHC II class expression, and decreased goblet cell numbers in the epithelium. These findings are similar to those of human ulcerative colitis and might suggest a similar pathogenesis at a cellular level.(3)

The exact cause of this condition remains unknown, and a multi-factorial etiology is highly suspected. In an ultrastructural study, it was concluded that CHUC was probably caused by a lipid-rich, ribosome-rich, coccoid to coccobacillary organism that possesses a cell membrane and range from 100 to 500 nm in size. This agent was suspected to be a Chlamydia-like organism.(10) In more recent reports, the infectious agent hypothesis was again brought to attention, since dogs completely recover after treatment with enrofloxacin.(2,4) In one study, there was demonstration of E. coli in 100% of the examined colonic samples with a polyclonal antibody, strongly associating this organism to the disease. In the same study, there was a comparison of this entity with granulomatous leptomeningitis of Beagle dogs, and malakoplakia and xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis in man, in which E. coli has also been incriminated, together with abnormal lysosomal function.(11) In 2009, Mansfield et al. observed remission of CHUC in Boxer dogs in correlation with the eradication of invasive intramucosal E. coli, further supporting the causal involvement of E.coli in the development of the disease in susceptible Boxer dogs.(5)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Davies DR, OHara AJ, Irwin PJ, Guilford WG. Successful management of histiocytic ulcerative colitis with enrofloxacin in two Boxer dogs. Aust Vet J. 2004;82:58-61.

3. German AJ, Hall EJ, Kelly DF, Watson ADJ, Day MJ. An immunohistochemical study of hisitiocytic ulcerative colitis of Boxer dogs. J Comp Path. 2000;122:163-175.

4. Hostutler RA, Luria BJ, Johnson SE, Weisbrode SE, Sherding RG, Jaeger JQ, et al. Antibiotic-responsive histiocytic ulcerative colitis in 9 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:499-504.

5. Mansfield CS, James FE, Craven M, Davies DR, OHara AJ, Nicholls PK, et al. Remission of Histioytic ulcerative colitis in boxer dogs correlates with eradication of invasive intramucosal Escherichia coli. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;23:964-969.

6. Sander CH, Langham RF. Canine histiocytic ulcerative colitis. A condition resembling Whipples disease, colonic histiocytosis and malakoplakia in man. Arch Pathol. 1968;85:94-100.

7. Stokes JE, Kruger JM, Mullaney T, Holan K, Schall W. Histiocytic ulcerative colitis in three non-boxer dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2001;37:461-465.

8. Turner JR. The Gastrointestinal tract. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:807-813.

9. Van Kruiningen HJ, Montali RJ, Strandberg JD, Kirk RW. A granulomatous colitis of dogs with histologic resemblance to Whipples disease. Path Vet. 1965;2:521-544.

10. Van Kruiningen HJ. The ultrastructure of macrophages in granulomatous colitis of Boxer dogs. Vet Pathol. 1975;12:446-459.

11. Van Kruiningen HJ, Civco IC, Cartun RW. The comparative importance of E. coli antigen in granulomatous colitis of Boxer dogs. APMIS. 2005;113:420-425.