WSC 2023-2035 Conference 2, Case 4

Signalment:

13-year-old, male castrated Ragdoll cat, feline (Felis catus)

History:

The animal presented with acute (2-3 week) onset of progressive non-painful bilateral hindlimb paraparesis that showed no improvement on corticosteroids. The lesion was localized to the L4 segment by neurology consult, but advanced imaging was declined due to cost. The animal had known chronic kidney disease that was otherwise well-managed and stable. The patient was euthanized due to poor prognosis.

Laboratory Results:

FIV/FELV testing was negative.

PARR on FFPE spinal cord tissue revealed a clonally rearranged T cell receptor gene.

Gross Pathology:

No significant gross lesions are observed in the central nervous tissues or lymphoid organs. Other findings include: (1) marked cardiomegaly (32.68 g) and left ventricular wall thickening; (2) gross bilateral enlargement of the parathyroid glands; and (3) bilateral irregular kidney contours.

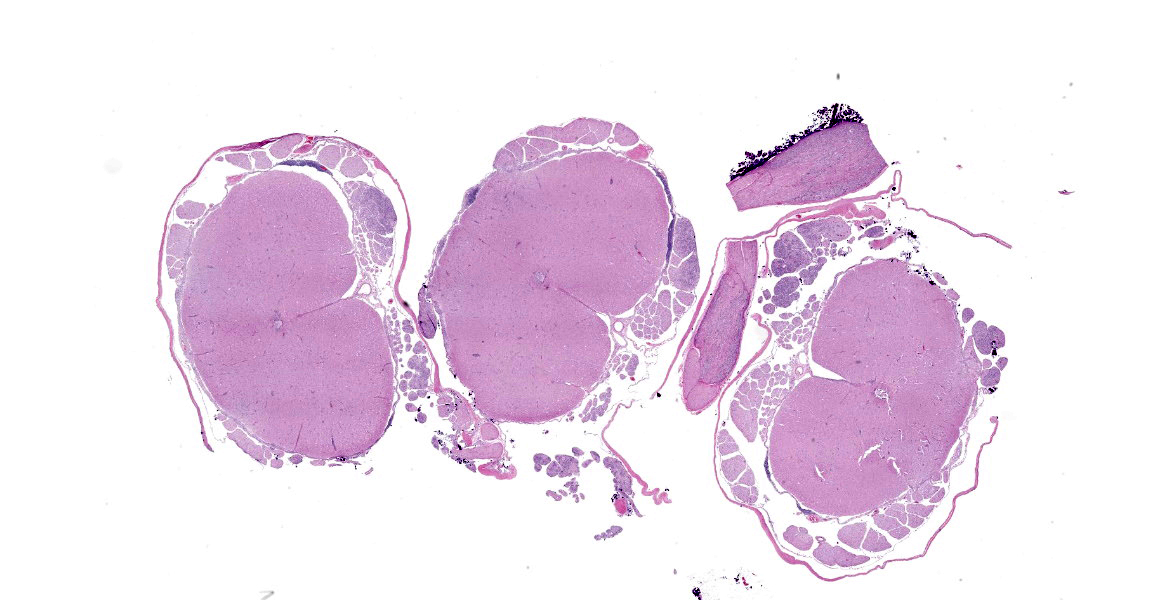

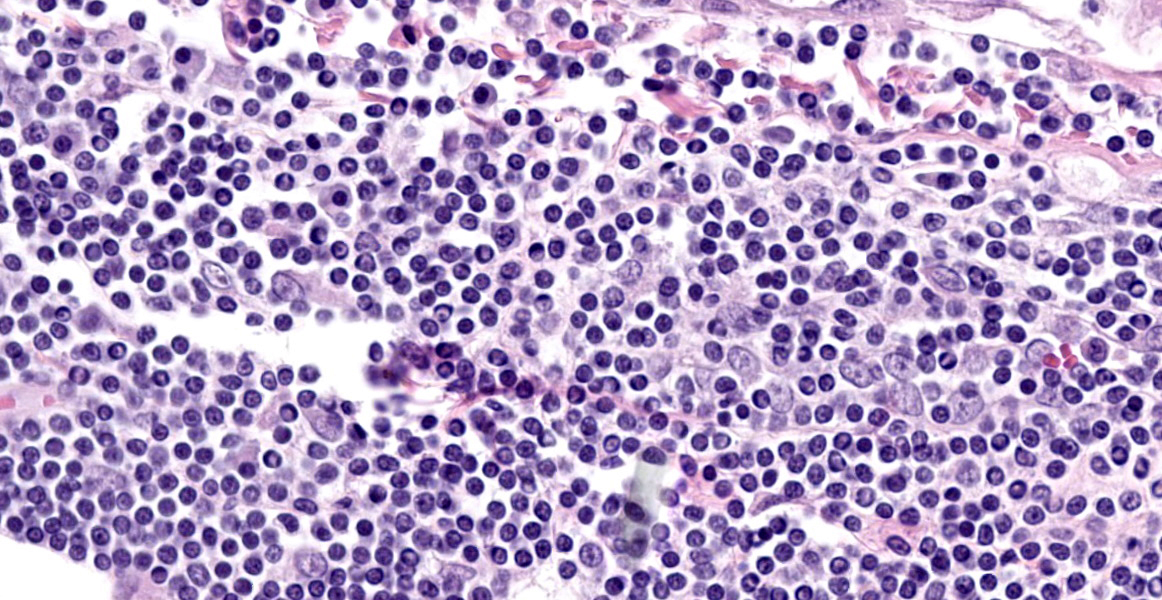

Microscopic Description:

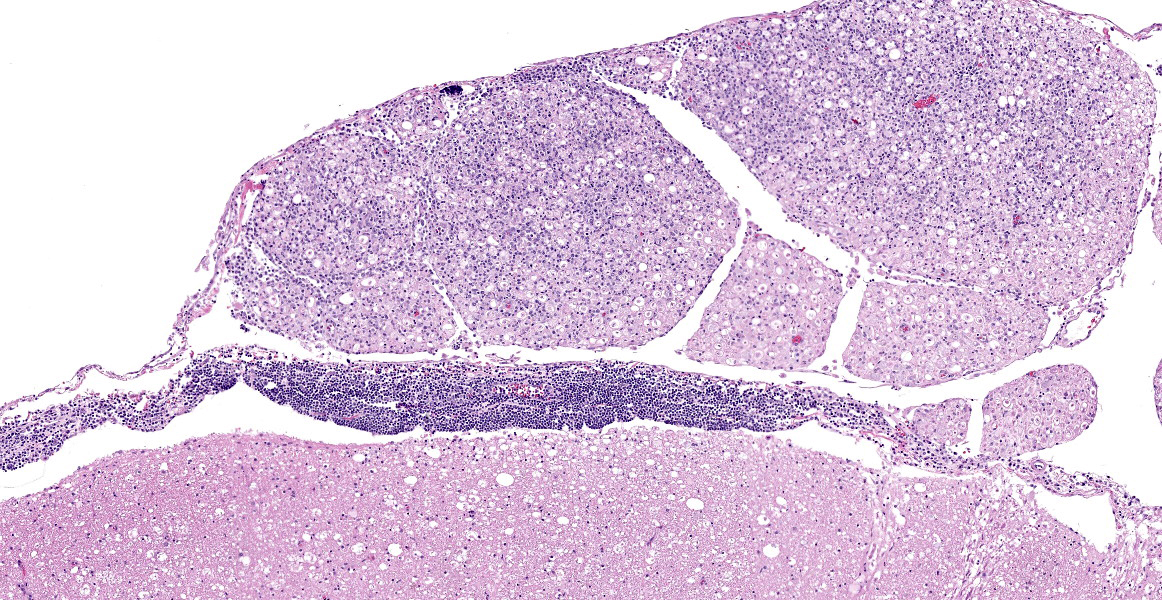

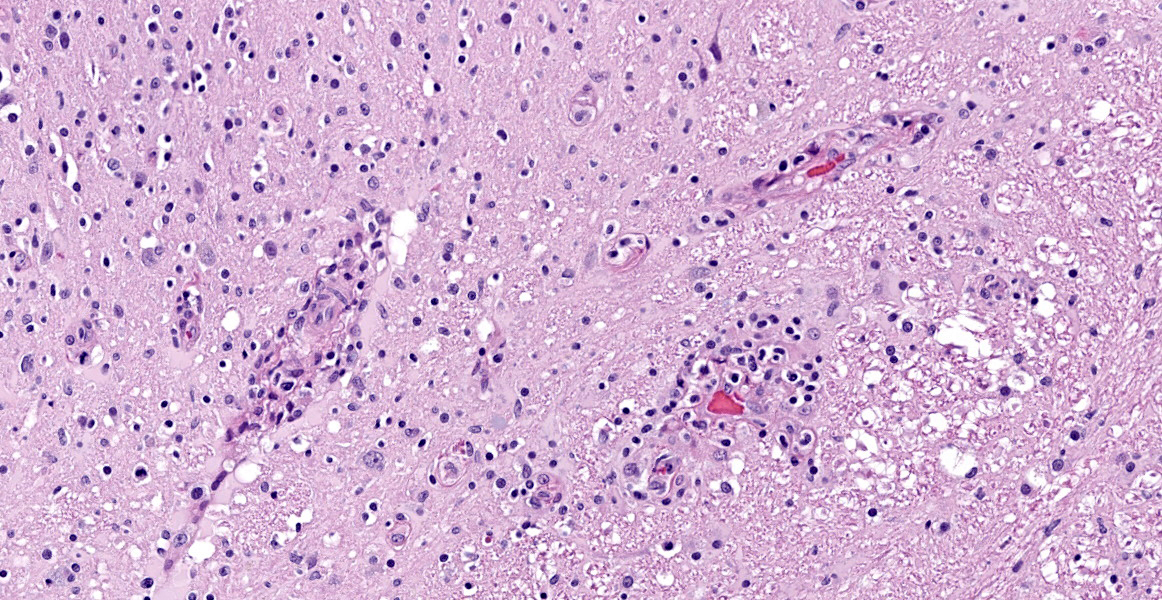

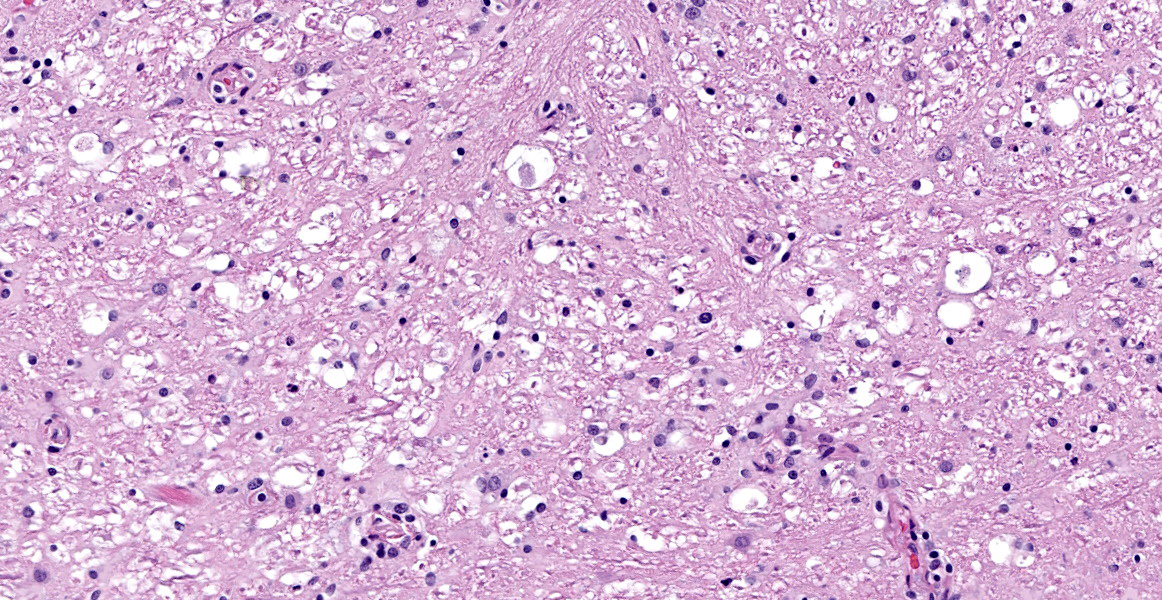

Spinal cord (L1-L5): Neoplastic intermediate to large (nuclei = 1.5 to 2 x RBC) round cells arranged in sheets expand the leptomeninges, infiltrate into the spinal nerve roots, and surround vessels (up to 6 cell layers thick) within the neuropil. Neoplastic cells have distinct cell borders and a small amount of amphophilic, granular cytoplasm. Nuclei are irregularly round with peripheralized chromatin and 1 variably distinct, basophilic nucleolus. There is moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. There are 6 mitotic figures in 0.237 mm2 (equivalent to 1 high power field). Separating neoplastic cells are a moderate number of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, rare plasma cells, and neutrophils. Throughout the neuropil there is increased cellularity due to neoplastic round cells and reactive glial cells. White matter myelin sheathes are occasionally dilated and contain a swollen axon (spheroid) or foamy macrophages (digestion chambers). Within the neuropil are frequent homogenous, basophilic staining, round, cytoplasmic inclusions (Lafora bodies). Occasionally neurons have peripheralized Nissl substance and yellow brown cytoplasmic pigment , interpreted as lipofuscin.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Spinal cord, L1-L5: Lymphoma (neurolymphomatosis), T-cell, with mild/moderate white and grey matter degeneration with multifocal Lafora bodies (incidental).

Contributor’s Comment:

The acute neurologic presentation in this case was associated with lymphoma of the spinal cord, spinal nerve roots, and leptomeninges. Infiltrates of neoplastic lymphocytes with a mixed inflammatory response extended into the leptomeninges of the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem (tissues not provided). Because some areas had more mixed inflammatory infiltrates, immunohistochemistry for FIP antigen was performed to rule out Feline Infectious Peritonitis and no immunoreactivity was noted. Immunohistochemistry for CD3 demonstrates strong immunoreactivity in the neoplastic cells infiltrating or expanding neural tissue, consistent with a T cell lymphoma. Small aggregates of CD20 expressing cells (B-cells) are attributed to secondary inflammation which does not infiltrate into neural tissue. Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue was submitted for PARR, which identified a clonally rearranged T cell receptor gene, further supporting the diagnosis of T cell lymphoma in this case. A complete postmortem examination was performed with histologic review of select samples of all major organ systems, and no involvement of any other organ systems was noted in this case (tissues not provided). While lymphomas in cats are common and nervous system involvement may be part of a multicentric process, primary lymphomas of the nervous system are considered rare.6 Primary lymphomas of the nervous system include both neuroinvasive and intravascular lymphomas. Our case is an example of the neuroinvasive subtype. Intravascular lymphoma is a rare subtype in which there is preferential accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes within small blood vessels in the central nervous system (CNS) and extraneurally in some organs. This usually occurs without leukemia or systemic mass lesions. Complete vessel occlusion by neoplastic cells can lead to infarction in these cases.6

When there is diffuse infiltration of malignant lymphoid cells into peripheral nerves, the term neurolymphomatosis is used.5,8 This is most common in humans due to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and may encompass cases with or without CNS involvement. In humans, it is almost exclusively B cell origin, though rare reports of T cell associated lymphomas have been reported.4 Though a distinct mechanism for neurotropism has not been identified in either human or veterinary literature, CD56 (NCAM, neural cell adhesion molecule) has been implicated.7,9

There have been scattered case reports of neurotropic lymphoma or neurolymphomatosis of cats in the veterinary literature.3,5,7,10-14,16,18,19 An older case series and more recent studies have also described primary central nervous system feline lymphoma with variable gross and clinical presentations and immunophenotypes.1,11,14,15,19 There is roughly equal distribution of both T and B cell lineages reported in both case reports and case series, which contrasts to the majority B cell immunophenotype reported in humans.4 The most common location for primary CNS lymphoma in cats is the spinal cord. Similarly, peripheral nervous system (PNS) involvement can occur exclusively in the PNS or simultaneously with CNS lymphoma.

The clinical (antemortem) diagnosis of primary nervous system lymphoma may be challenging. Advanced imaging combined with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis may offer the best chance at antemortem diagnosis, but often results can vary and be nonspecific.1 CSF analysis was not performed in this case. Gross findings may be minimal, as neoplastic infiltrates may not create grossly visible enlargement or a discrete mass effect. Histologic examination and immunohistochemistry remain the gold standard in both human and veterinary medicine.17 Important clinical differential diagnoses for hindlimb paresis/paralysis include thromboembolic disease (such as saddle thrombus or fibrocartilaginous embolism), demyelinating diseases (i.e. peripheral neuropathies), other neoplasms of the spinal cord or spinal canal, infectious meningomyelitis/neuritis (e.g., Feline Infectious Peritonitis, toxoplasmosis, rabies), trauma, degenerative disk disease, neurotoxins (i.e. bromethalin), or metabolic abnormalities (such as hypoglycemia or electrolyte disturbances).

Contributing Institution:

Colorado State University

Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratories

Fort Collins, CO

https://vetmedbiosci.colostate.edu/vdl/

JPC Diagnosis:

Spinal cord and spinal nerves: Lymphoma.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent review of neurolymphomatosis and correctly notes that this entity presents a particular diagnostic challenge.

In addition to cats, neurolymphomatosis has been reported in a smattering of dogs and horses, often with minimal perivascular cuffing of clonal lymphocytes throughout the CNS.6 Clinical signs in affected animals are variable, typically non-specific, and stem from Wallerian degeneration of axons due to heavy lymphocytic infiltration of the peripheral nerves. The most common presenting complaints are single or multi-limb lameness, muscle weakness, monoparesis or plegia, and cauda equine syndrome, depending on the particular nerves affected.2

Antemortem diagnosis in humans is typically made on the basis of enlargement or enhancement of nerves and nerve roots on MRI and PET/CT images and the examination of peripheral nerve biopsy speciments.2 Even so, in one case study series, 45% of cases were diagnosed as neurolymphomatosis only at autopsy.17 In veterinary medicine, MRI exam is typically cannot provide definitive diagnosis due to the lack of historically consistent MRI findings among histologically confirmed cases of neurolymphomatosis.6

Postmortem gross findings can include bilateral asymmetrical or symmetrical thickening of the spinal or cranial nerves, though it is more common to find no gross lesions, as illustrated in this case. Definitive diagnosis requires histologic evidence of infiltration of nerve fascicles of B- or T-cell lymphocytes in rows between peripheral nerve axons and within intraneural and epineural spaces.6

Conference participants discussed two histologic features of this case that do not strictly fit the case definition of neurolymphomatosis: the abundant mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of B lymphocytes and plasma cells within the leptomeninges and the presence of abundant neoplastic T lymphocytes within the spinal cord parenchyma. Prior to reviewing IHC results, conference participants assumed meningeal lymphocytes were an extension of the neoplastic process; however, IHC results convincingly indicate that the meningeal lymphocytes are B lymphocytes admixed with fewer plasma cells and few histiocytes, indicating that these aggregates most likely represent chronic inflammation. Conference participants felt the chronic inflammation could be plausibly explained by the presence of long-standing neoplastic infiltration of the spinal nerves, though this feature has not been consistently described in this entity. More confounding was the presence of neoplastic lymphocytes within the spinal cord. Neurolymphomatosis is, by definition, neoplastic infiltration of the peripheral nervous system without infiltration of other organs. The presence of lymphocytes within the spinal cord parenchyma, along with the inability to conclusively rule out other lymphomatous foci elsewhere in the animal, led to a conservative JPC diagnosis of lymphoma.

References:

- Durand A, Keenihan E, Schweizer D, et al. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging features of lymphoma involving the nervous system in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2022;36(2):679-693.

- Fantaconi N, Walker JJA, Ives EJ. What is your neurologic diagnosis? 2020;257(10):1013-1016.

- Fondevila D, Vilafranca M, Pumarola M. Primary central nervous system T-cell lymphoma in a cat. Vet Pathol. 1998;35(6):550-553.

- Gan HK, Azad A, Cher L, Mitchell PL. Neurolymphomatosis: diagnosis, management, and outcomes in patients treated with rituximab. Neuro Oncol. 2010; 12(2):212-215.

- Higgins MA, Rossmeisl JH Jr, Saunders GK, Hayes S, Kiupel M. B-cell lymphoma in the peripheral nerves of a cat. Vet Pathol. 2008;45(1):54-57.

- Higgins RJ, Bollen AW, Dickinson PJ, Siso-Llonch S. Tumors of the Nervous System. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Species. 5th ed. Wiley Blackwell; 2020:872-877.

- Hsueh CS, Tsai CY, Lee JC, et al. CD56+ B-cell neurolymphomatosis in a cat. J Comp Pathol. 2019;169:25-29.

- Kelly JJ, Karcher DS. Lymphoma and peripheral neuropathy: a clinical review. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31(3):301-313.

- Kern WF, Spier CM, Hanneman EH, Miller TP, Matzner M, Grogan TM. Neural cell adhesion molecule-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma: a rare variant with a propensity for unusual sites of involvement. Blood. 1992;79(9):2432-2437.

- Linzmann H, Brunnberg L, Gruber AD, Klopfleisch R. A neurotropic lymphoma in the brachial plexus of a cat. J Feline Med Surg. 2009;11(6):522-524.

- Mandara MT, Domini A, Giglia G. Feline lymphoma of the nervous system: immunophenotype and anatomical patterns in 24 cases. Front Vet Sci. 2022; 9:959466.

- Mandrioli L, Morini M, Biserni R, Gentilini F, Turba ME. A case of feline neurolymphomatosis: pathological and molecular investigations. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24(6):1083-1086.

- Mellanby RJ, Jeffery ND, Baines EA, Woodger N, Herrtage ME. Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of lymphoma involving the brachial plexus in a cat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2003;44 (5):522-525.

- Mello LS, Leite-Filho RV, Panziera W, et al. Feline lymphoma in the nervous system: pathological, immunohistochemical, and etiological aspects in 16 cats. Pesq Vet Bras. 2019;39(06):393-401.

- Rissi DR, McHale BJ, Miller AD. Primary nervous system lymphoma in cats. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2022;34(4):712-717.

- Sakurai M, Azuma K, Nagai A, et al. Neurolymphomatosis in a cat. J Vet Med Sci. 2016;78(6):1063-1066.

- Shree R, Goyal MK, Modi M, et al. The diagnostic dilemma of neurolymphomatosis. J Clin Neurol. 2016;12(3):274-281.

- van Koulil Q, Santifort KM, Beukers M, Ioannidis M, Van Soens I. Neurolymphomatosis in a cat with diffuse neuromuscular signs including cranial nerve involvement. Vet Rec Case 2022; 10:e482.

- Zaki FA, Hurvitz AI. Spontaneous neoplasms of the central nervous system of the cat. J Small Anim Pract. 1976;17 (12):773-782.