Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 3

September 6th, 2017

CASE I: 10N0979 (JPC 4019127).

Signalment: 1 year-old, male, Domestic longhaired cat (Felis catus).

History: This tissue was from a stray cat hit by a car 3 weeks prior to presentation to the VMTH. On presentation the cat was non-ambulatory and obtunded, had a fractured right pelvic limb, absent voluntary movement of both pelvic limbs and the left thoracic limb, and no pain perception. Due to a grave prognosis, the cat was humanely euthanized.

Gross Pathology: This cat was thin and had a healing transverse fracture of the right distal tibia. The bladder was distended and had a severely compromised thickened wall with large irregular areas of full thickness necrosis (considered the result of trauma). The brain and spinal cord were grossly normal.

Laboratory results: None provided.

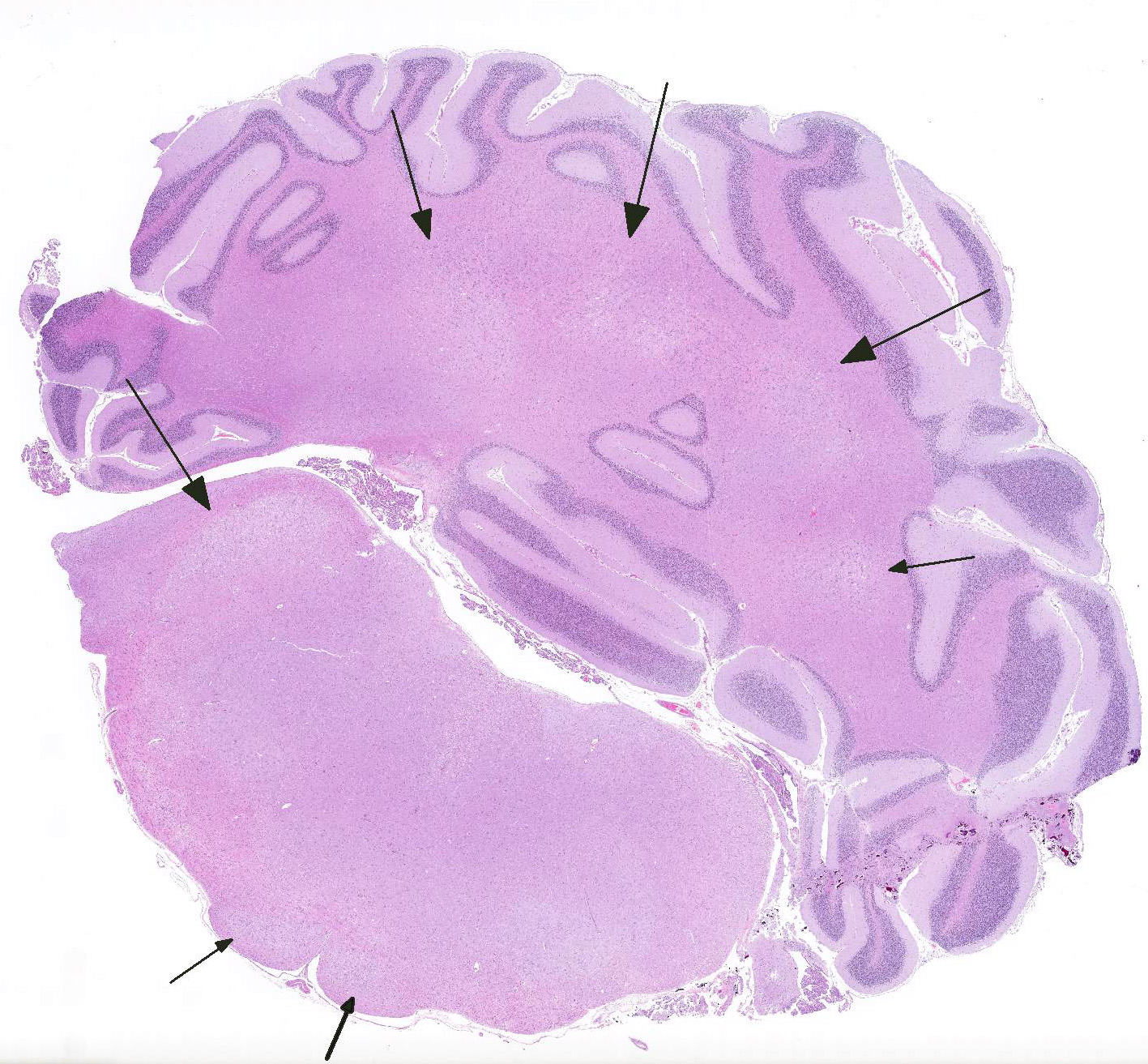

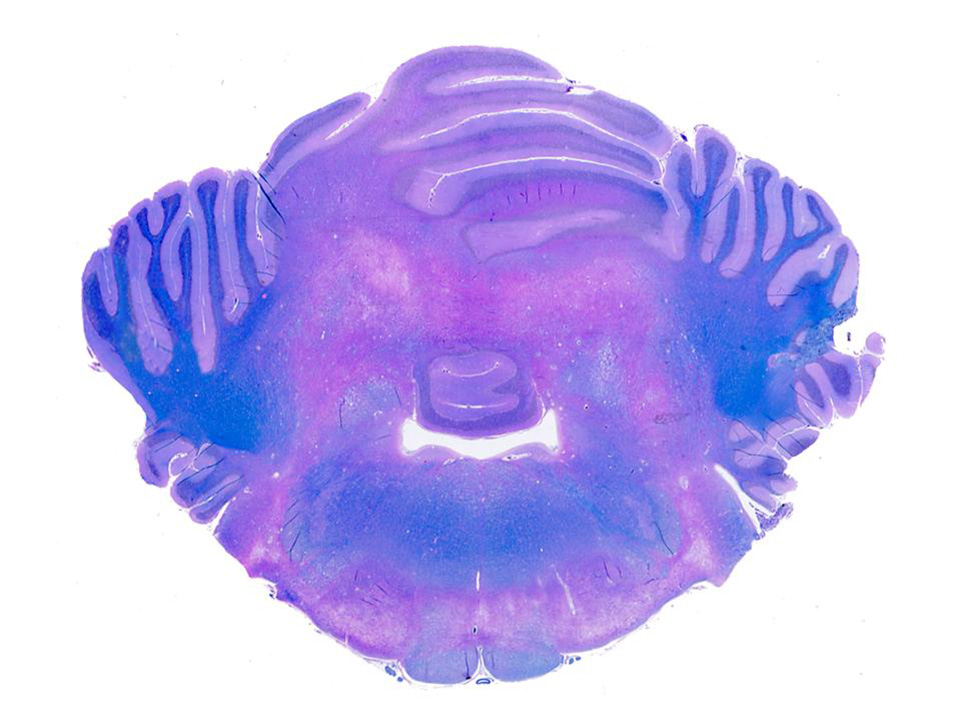

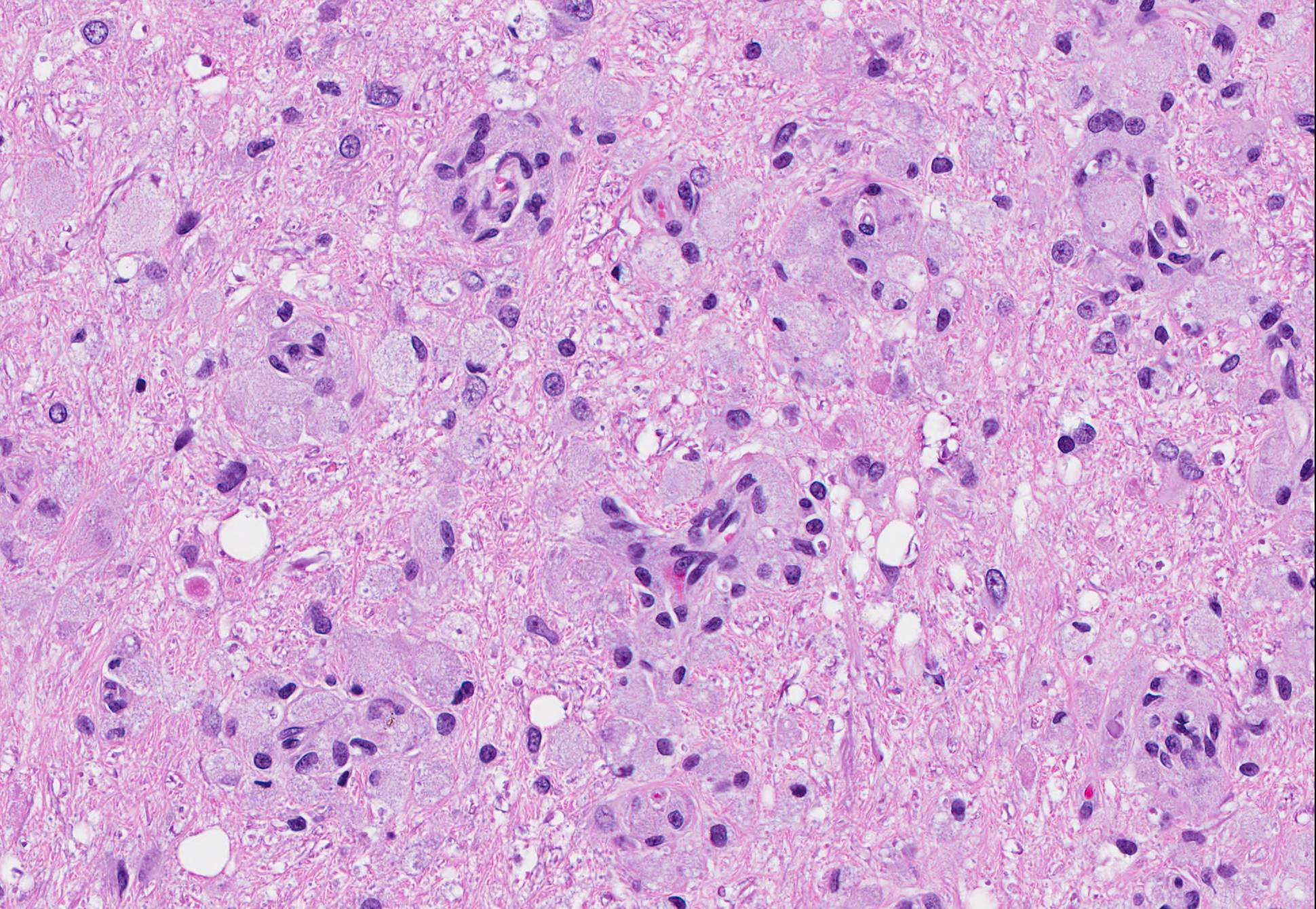

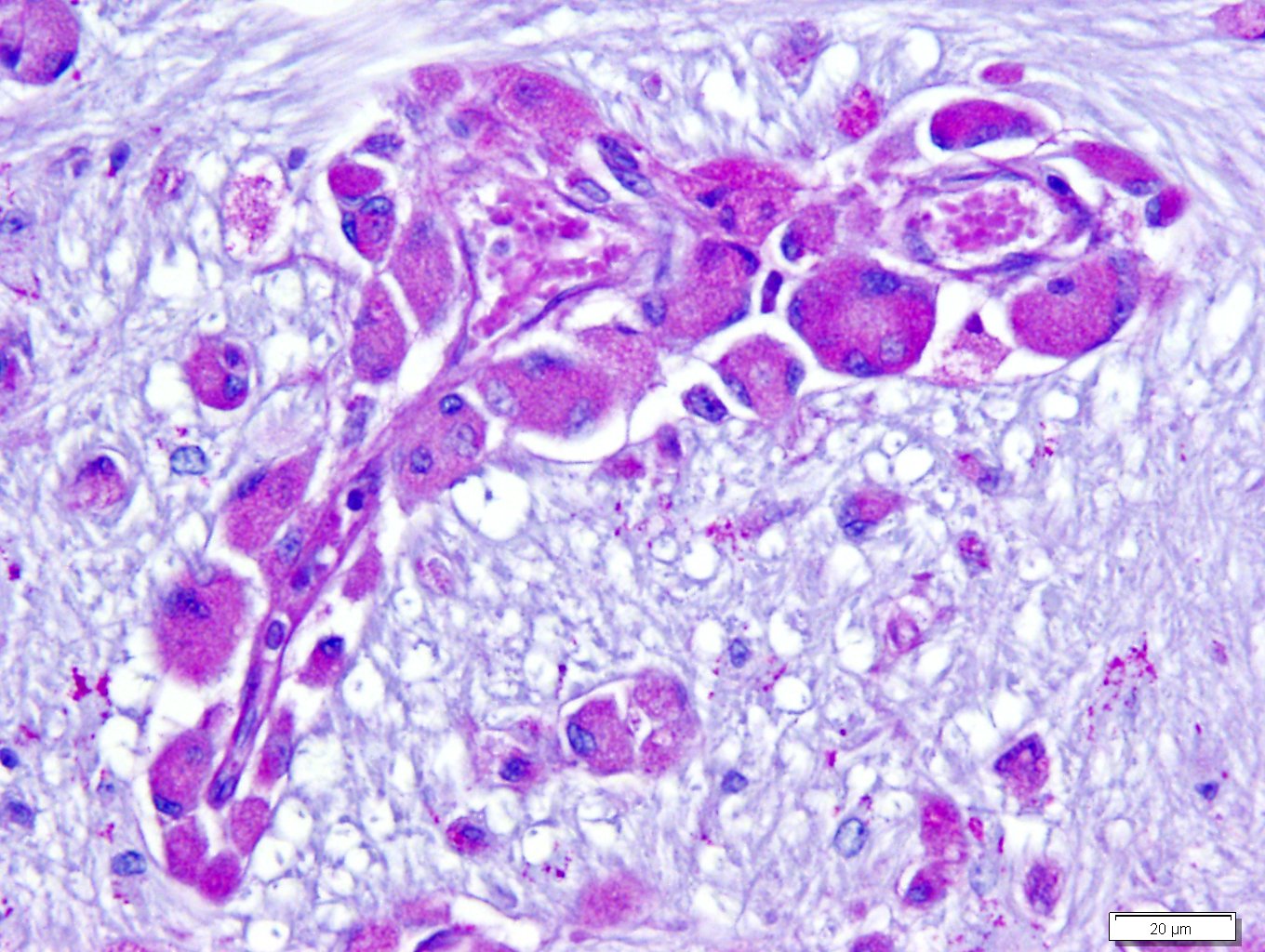

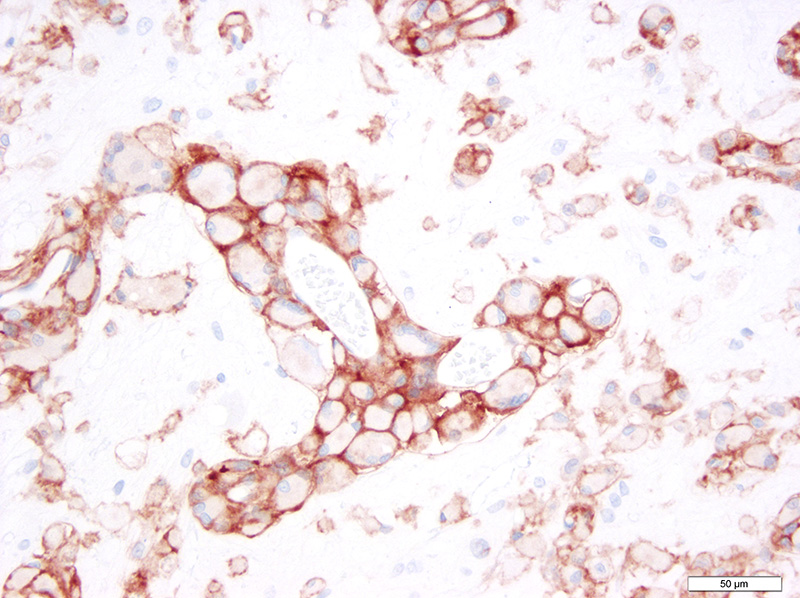

Microscopic Description: Brain: There is severe bilateral, regional and symmetrical demyelination of the white matter (WM) in the brain and spinal cord of varying severity. There are widespread angiocentric accumulations of large mononuclear cells. These cells are CD18 immunoreactive (macrophages) that have abundant, distended pale finely vacuolated eosinophilic cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, and are occasionally multinucleated. In areas of demyelination in the WM, there is scattered axonal necrosis with axonal spheroids and reactive astrogliosis. The large globoid mononuclear cells are PAS positive, but stain non-metachromatically. The gray matter appears unaffected.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis: Brain and spinal cord: Severe bilaterally symmetrical perivascular histiocytosis and demyelination (consistent with globoid cell-like leukodystrophy).

Contributors Comment: Globoid cell leukodystrophy is a rare lysosomal storage disease (sphingolipidosis) that involves the white matter of the central and peripheral nervous system. The disease has been described in humans (Krabbes disease), mutant twitcher mice, rhesus monkeys, polled Dorset sheep, and domestic cats. In all affected animals except the domestic cat there is a demonstrated autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. 1,2,4,5,7 One report documents globoid leukodystrophy in 2 female kittens that resulted from inbreeding of common ancestors, which suggests a hereditary basis in cats as well.1 Clinical signs appear at a young age (1-3 months of age) and initially consist of ataxia, hypermetria, tremors, and proprioceptive deficits which progress to blindness, anorexia, muscle atrophy, and paraplegia. Death occurs by 1-2 years of age.6

The disease occurs due to a deficiency in galactocerebrosidase enzyme activity resulting in an accumulation of galactosylsphingosine (psychosine) within Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes.1 It remains undetermined if accumulation of this intracellular material is a result of abnormal myelin synthesis or abnormal breakdown. Psychosine is cytotoxic thus resulting in degeneration and necrosis of oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells (hence the extensive demyelination) and extracellular release. Macrophage phagocytose and accumulate psychosine and are the hallmark globoid cells seen on histopathology and typically aggregate perivascularly in the white matter.3 Typical histological findings consist of bilaterally symmetrical white matter demyelination and striking perivascular hypercellularity characterized by numerous plump globoid macrophages.6 The centrum semiovale, corona radiate, corpus callosum, optic tract, and cerebellar medullare are most severely affected.6 Peripheral subpial areas are the most commonly affected portion of the spinal cord.6 The intracytoplasmic material within macrophages is typically PAS positive, non-metachromatic, and non-sudanophilic.1 Leukocyte immunohistochemical markers such as CD18 or MAC1 can be used to confirm globoid cells are of macrophage/microglial origin.

JPC Diagnosis: Cerebellum and brain stem: Histiocytosis, perivascular, multifocal, moderate with demyelination and gliosis, Domestic longhair, feline.

Conference Comment: This case nicely demonstrates lesions attributable to globoid-cell leukodystrophy (Krabbes disease) in a young cat. Participants discussed the bilaterally symmetrical areas of pallor within deep spinocerebellar and brain stem pyramidal tracts corresponding to white matter vacuolation and histiocytosis. Histiocytes are described as having an amphophilic granular cytoplasm. There is evidence of demyelination characterized by axonal swelling (spheroids) and dilated myelin sheaths with macrophages phagocytizing myelin (Gitter cells in digestion chambers). Participants reviewed the immunohistochemical stains submitted by the contributor including Luxol fast blue that further emphasizes the severity of the demyelination and CD18 which classifies perivascular engorged cells as histiocytic in origin. Participants were reminded that the affected histiocytes are clustered around vessels in an attempt to leave the tissue but are too large to pass between endothelial cells and enter circulation.

The contributor provides a complete summary of the pathogenesis of globoid cell leukodystrophy which was also discussed by participants. The conference moderator lead participants in reviewing the broad categories of storage diseases: induced and inherited. In general, storage diseases are characterized by accumulation of a substance that exceeds the capacity of that cell to digest or dispose of that substance. Inherited storage diseases are almost always proved to be due to lysosomal deficits, and commonly occur in young animals owing to the fact that they are caused by genetic defects. Inherited storage disease categories were mentioned: sphingolipidoses, glycoproteinoses, mucopolysaccharidoses, glycogenoses, mucolipidoses, ceroid-lipofuscinoses, and Lafora disease. Induced storage diseases have been produced by ingestion of plants containing swainsonine (an indolizidine alkaloid) and plants of the Trachyandra spp. and Phalaris spp. genera.1

Finally, of the inherited storage diseases, the moderator reviewed sphingolipidoses:

|

Sphingolipidosis category |

Common name |

Deficiency |

Accumulation |

Cellular vacuolation |

Animals affected |

|

GM1 Gangliosidosis |

|

?-galactosidase |

GM1 ganglioside, some oligosaccharides |

Neurons & macrophages |

Cats, dogs, cattle, sheep |

|

GM2 Gangliosidosis |

Tay Sachs; Sandoff disease |

?-Hexosaminidase |

GM2 ganglioside, +/- globoside |

Neurons & macrophages |

Cats, dogs, Yorkshire pigs |

|

Glucocerebrosidosis |

Gauchers disease |

Glucocerebrosidase |

Glucocerebroside |

Neurons & macrophages (not in cerebellar Purkinje cells or spinal cord) |

Sydney Silky Terrier |

|

Sphingomyelinosis |

Niemann-Pick type A |

Sphingomyelinase |

Sphingomyelin, cholesterol and ganglioside |

Neurons & macrophages |

Cats, miniature poodles |

|

Sphingomyelinosis |

Niemann-Pick type C |

NPC 1 or NPC 2 proteins |

NPC 1 or NPC 2 proteins |

Neurons & macrophages |

Cats, Boxer dogs |

|

Galactosialidosis |

|

?-galactosidase & ?-neuraminidase |

Gangliosides and oligosaccharides |

Neurons & macrophages |

Schipperke dogs |

|

Galactocerebrosidosis |

Globoid cell leukodystrophy; Krabbes disease |

Galactocerebrosidase (GALC) |

Galactocerebroside and galactosylsphingosine (psychosine) |

Macrophages only (globoid cells) |

Cats, mutant Twitcher mice4, polled Dorset sheep |

Chart adapted from: Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:284-293.

Several attendees expressed concern with the diagnosis in this case, noting the previous history severe trauma, the lack of any mention of lesions elsewhere in the central nervous system, as well as the lack of any specific identification of material contained within macrophages in the examined sections. Moveover, as is the case with strays, there is a lack of a familial history. There was general concern that the lesion may be a long-term sequel to the severe neurologic trauma noted weeks prior to this case.

Contributing Institution:

University of California, Davis

Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital

Anatomic Pathology Service

References:

- Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:284-293, 301-303.

- Johnson, K. Globoid Leukodystrophy in the Cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1970:157(12):2057-2064.

- Kobayashi T, Yamanaka T, Jacobs J, et al. The twitcher mouse: an enzymatically authentic model of human globoid cell leukodystrophy (Krabb disease). Brain Res. 1980;202:479-483.

- Krinke GJ. Neuropathologic analysis of the peripheral nervous system. In: Bolon B, Butt MT, ed. Fundamental Neuropathology for Pathologists and Toxicologists. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2011:378-379.

- Maxie MG, Youssef S: The nervous system. In: Maxie MG ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:381-382.

- Pritchard D, Napthine D, Sinclair A. Globoid cell leucodystrophy in Polled Dorset sheep. Vet Path. 1980;17:399-405.

- Sigurdson C, Basaraba R, Mazzaferro E, Gould D. Globoid Cell-like Leukodystrophy in a Domestic Longhaired Cat. Vet Pathol. 2002;39:494-496.

- Summers B, Cummings J, de Lahunta A. Veterinary Neuropathology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995:220-221.

- Wenger, D, Victoria T, Rafi M, Luzi P, Vanier M, Vite C, Patterson D, Haskins M. Globoid cell leukodystrophy in Cairn and West Highland White Terriers. J Hered. 1999; 90:138-142.

- Zachary JF: Nervous system. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:931-932.