CASE II: 19-31-3 (JPC 4166464)

Signalment:

Adult Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus)

History:

An adult Syrian hamster was evaluated by veterinary staff at the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill for signs of malaise, including a hunched posture, dehydration, weight loss, and facial swelling with patchy alopecia. Eight weeks earlier, the hamster had arrived from an academic institution with 19 other male and female hamsters. The hamsters were STAT2 knockouts that were purchased for a respiratory syncytial virus study and were clinically healthy upon arrival. The hamsters had not yet been infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Upon physical examination, the hamster had multiple cutaneous masses along the face and limbs. Many of the other hamsters had similar cutaneous masses and/or a firm palpable abdominal mass. The entire cohort was culled.

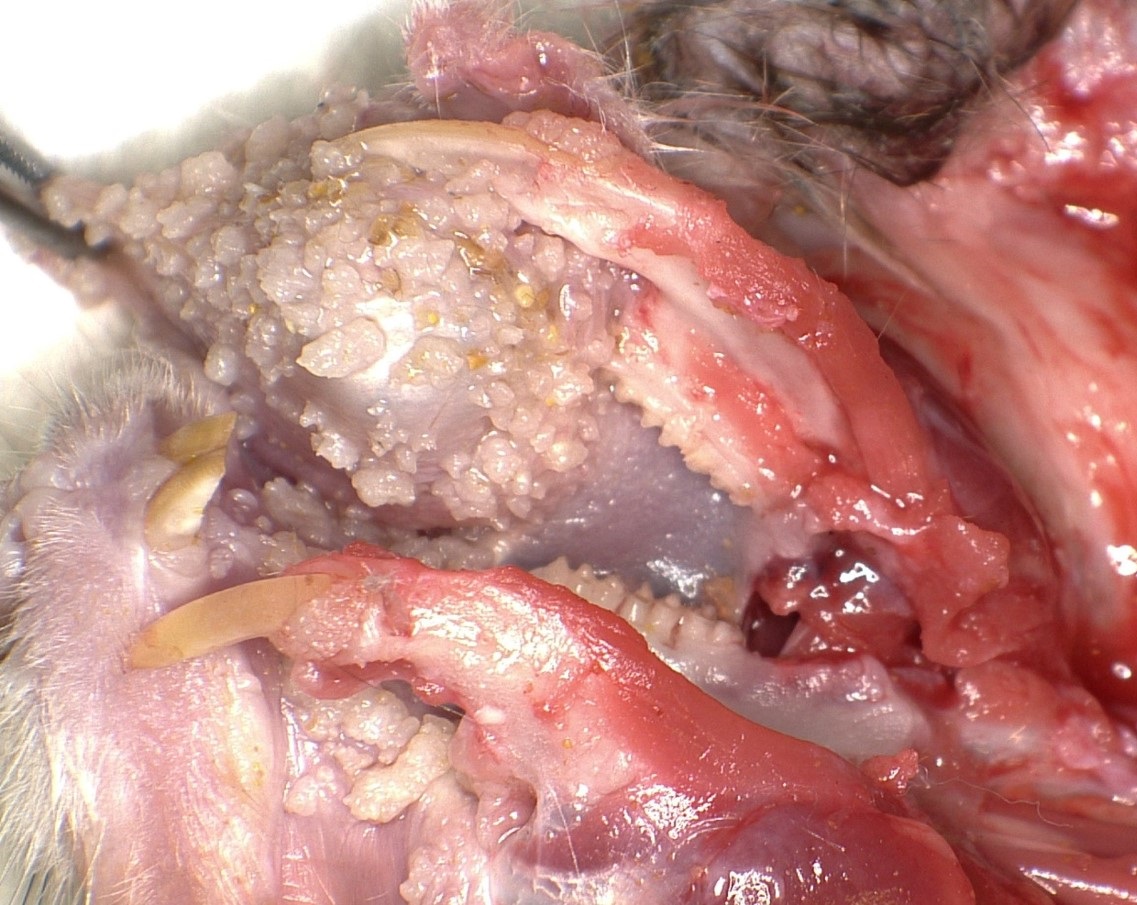

Gross Pathology:

Bilaterally along the haired skin overlying the cheek pouches, ventral mandible, and limbs, there were innumerable, multifocal to coalescing, 2-20 mm in diameter, raised, semi-firm, pale pink to grey, cutaneous masses with varying degrees of alopecia. A draining tract associated with the masses along the left cheek pouch was present. Bilaterally along the mucosa of the cheek pouches, there were innumerable, multifocal, pinpoint to 3 mm in diameter, exophytic, pale tan, firm, papillomatous masses.

Laboratory Results:

Prior to arrival, this hamster tested serologically positive for hamster polyomavirus and negative for Encephalitozoon cuniculi, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, pneumonia virus of mice, reovirus 3, Sendai virus, simian virus 5, Clostridium piliforme, and were PCR negative for pinworms and fur mites. PCR for papillomavirus on samples of the cheek pouch tumors was negative. Electron microscopy on the skin tumors did not reveal any viral particles.

Microscopic Description:

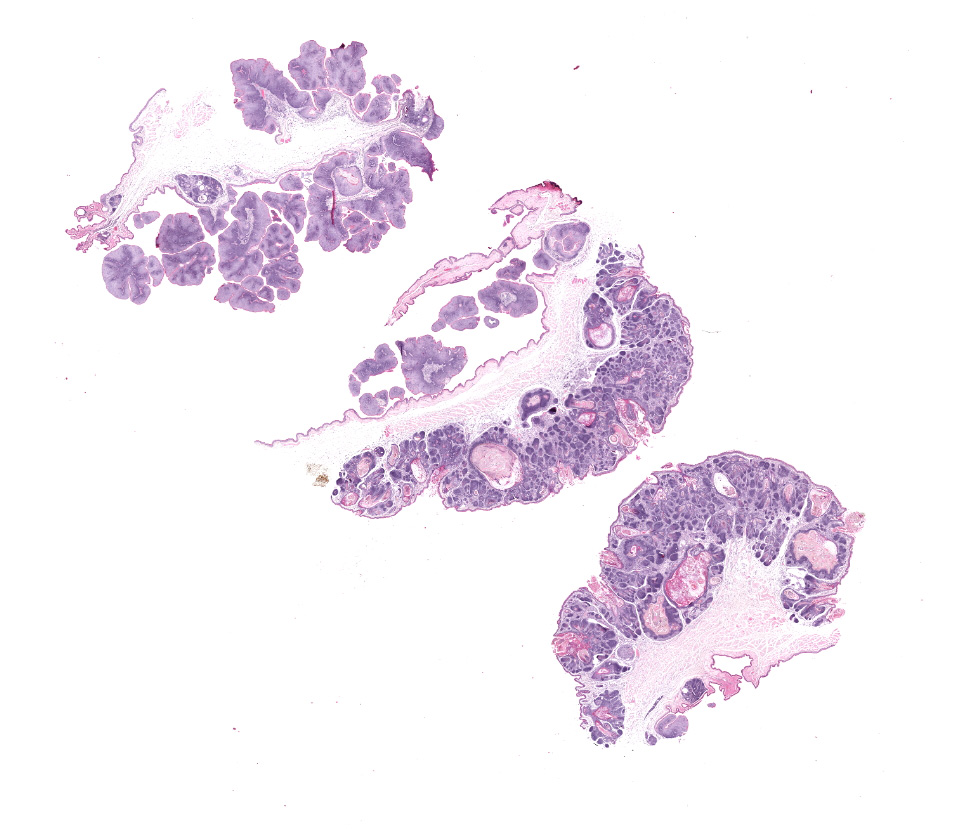

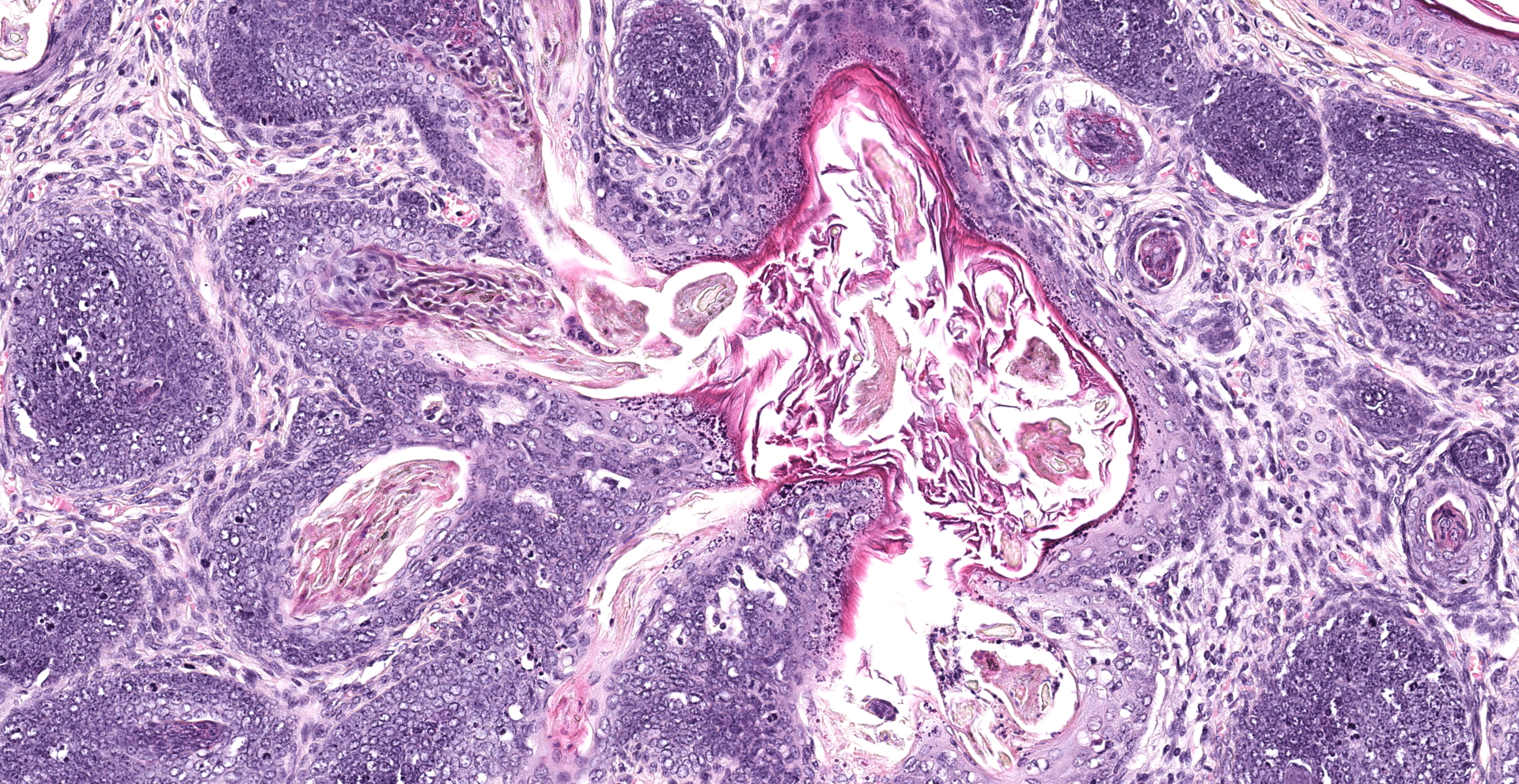

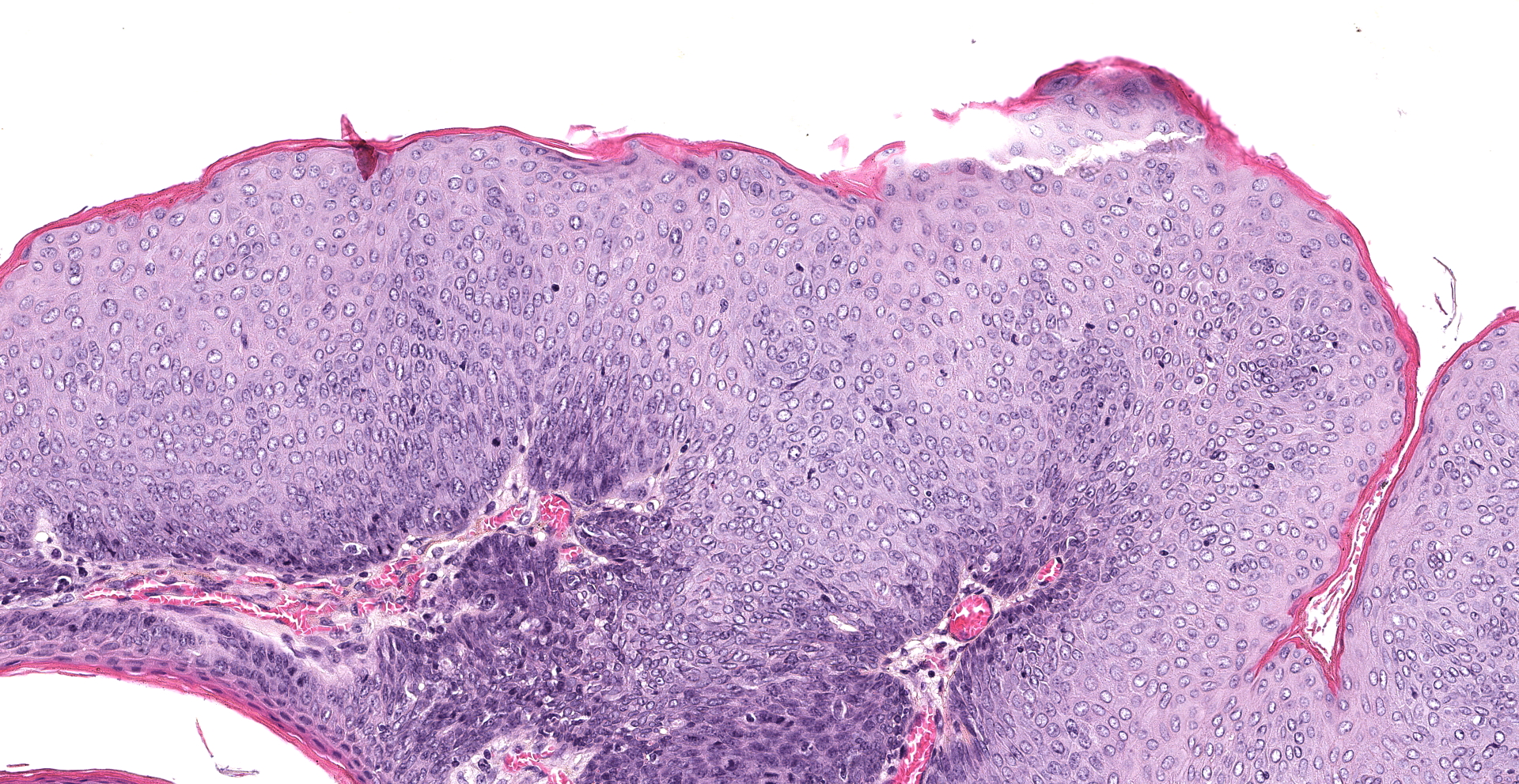

Haired skin, oral mucosa (cheek pouch): Three sections of cheek pouch containing haired skin and oral mucosa are examined. Markedly expanding the dermis are multifocal to coalescing, unencapsulated, well demarcated, neoplastic masses with a cystically dilated central cavity and a superficial pore that communicates with the surface. Cystic centers resemble dilated infundibula and have a wall of stratified squamous epithelium with keratohyalin granules and orthokeratotic stratum corneum which accumulates centrally. Connected to and radiating from the cystic cavities are multiple linear primitive hair follicle structures with distinct follicular differentiation (structure and cytodifferentiation): matrical cell differentiation (forming hair bulbs), internal root sheaths with red trichohyalin granules, vacuolated external root sheaths (agranular), and occasional abortive hair shafts with ghost cell cornification. Connected to the linear

follicle structures are multifocal, small lobules of epithelial cells resembling well-differentiated sebocytes. There are 82 mitotic figures per 10 high power fields (area 2.37 mm2) with occasional bizarre mitoses; the mitotic rate is most prominent within matrical cell differentiated populations. There is mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. There is frequent necrosis of individual neoplastic cells throughout all components. Areas of central cornification within cystic infundibular structures occasionally contain small colonies of coccoid bacteria with few viable and degenerative heterophils. The masses are separated by a fibrovascular stroma composed of moderately increased numbers of plump fibroblasts within a loose collagenous matrix containing numerous small caliber blood vessels. Scattered throughout the supporting stroma are moderately increased numbers of perivascular to interstitial mast cells and few heterophils.

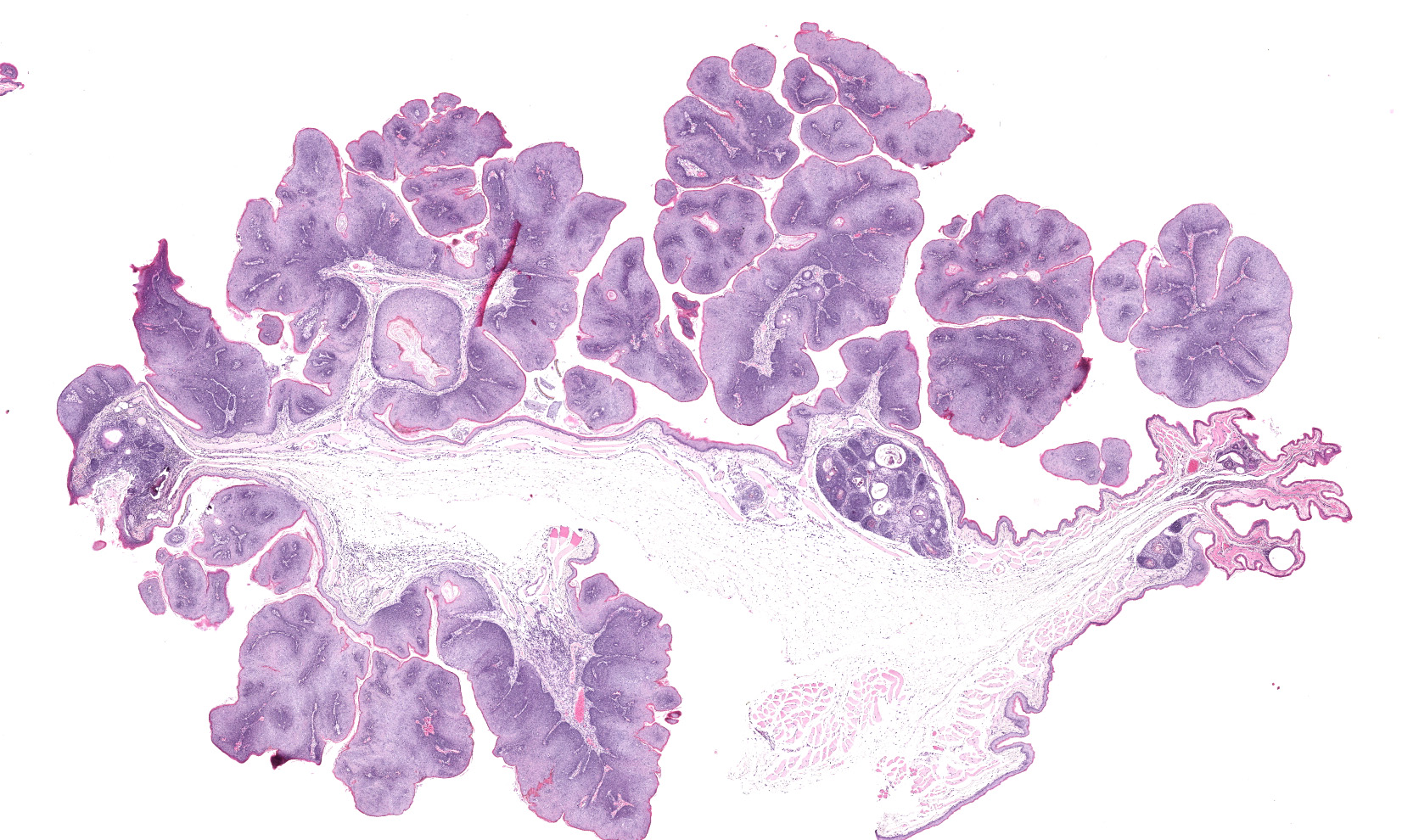

The mucosal epithelium is multifocally, markedly expanded by unencapsulated, well-demarcated, exophytic papillary masses composed of well-differentiated squamous epithelium that is supported by a thin fibrovascular stalk. The neoplastic epithelial cells are polygonal and have distinct cell borders, a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a central round nucleus with 0-1 prominent nucleoli, and finely stippled chromatin. There is moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis.

There are 66 mitotic figures per 10 high power fields (area 2.37 mm2). There is frequent necrosis of individual neoplastic cells. Occasionally, the masses along the oral mucosa contain central sebocyte differentiation and basilar trichoblastic differentiation as described within the masses in the haired skin (above). The supporting stroma is multifocally infiltrated by moderate numbers of mast cells, fewer heterophils, and rare lymphocytes and plasma cells. Along the overlying stratum corneum, there are occasional, small colonies of coccoid bacteria.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Cheek pouch:

1. Haired skin: Multifocal to coalescing trichoepitheliomas with bacterial colonization and mild heterophilic dermatitis.

2. Buccal mucosa: Multifocal squamous papillomas with minimal adnexal differentiation and mild heterophilic stomatitis.

Contributor's Comment:

The gross and histopathologic haired skin lesions in this case are consistent with trichoepitheliomas secondary to hamster polyomavirus (HaPyV) infection in a signal transducer and activator of transcription protein 2 (STAT2) knockout hamster.

HaPyV is an non-enveloped, double stranded DNA virus that is reported to cause trichoepitheliomas and epizootic transmissible lymphoma in hamsters.2-7 Other tumors types associated with HaPyV have not been described.1 Prevalence of HaPyV is uncommon in laboratory hamster populations.1 In this case, immunosuppression likely predisposed this hamster to infection and tumorigenesis by HaPyV. Animals without STAT2 are unable to transcriptionally respond to interferons resulting in increased susceptibility to viral infections.5,9 Lymphoma typically occurs within epizootically infected populations, whereas enzootically infected populations are more prone to developing trichoepitheliomas.2,3 Trichoepitheliomas develop in hamsters 3-12 months of age. Lymphoma in HaPyV infected hamsters typically develops in young hamsters.2-6

Transmission of HaPyV is thought to occur by ingestion of infected feces or urine (hamsters are naturally coprophagic).2,6 HaPyV persists within renal tubular epithelium and is shed into the urine and can also be present in infected keratinocytes and enterocytes within feces.2 HaPyV has a tropism for undifferentiated keratinocytes and lymphocytes, resulting in trichoepitheliomas and lymphoma, respectively. Trichoepitheliomas typically arise on the face and feet, although they can be found anywhere on the body. Lymphoma most often develops within the mesentery, intestines, liver, kidney, and thymus.2,3,6 HaPyV may replicate within cells resulting in lysis or transform cells without replication. Similar to papillomaviruses, HaPyV exhibits viral replication within trichoepitheliomas. While HaPyV is oncogenic, tumor development is not critical to viral survival and replication. Therefore, hamsters can be subclinically infected.2

Diagnosis of HaPyV associated disease is typically made on histologic diagnosis of trichoepitheliomas and lymphoma. Trichoepitheliomas unassociated with HaPyV have not been described, and lymphoid tumors unassociated with HaPyV are uncommon in young hamsters. Further diagnostics may include virus isolation, PCR, serology, and electron microscopy. Prior to arrival at UNC - Chapel Hill, the hamster tested serologically positive for HaPyV. The negative electron microscopy results in this case do not rule out HaPyV as finding virions on electron microscopy is often challenging.2

To our knowledge, oral papillomas or other oral tumors have not been reported with HaPyV infected hamsters. Given the mild adnexal differentiation associated with the papillomas along the oral mucosa in this case, these tumors are thought to have arisen from HaPyV infection. A lack of further trichoepithelial differentiation within this population of tumors may be due to the absence of follicular epithelium along the oral mucosa. Samples of the check pouch tumors tested negative for papillomavirus on PCR.

In conclusion, this report describes a case of trichoepitheliomas and oral squamous papillomas, thought to be caused by HaPyV.

Contributing Institution:

1. University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill

a. https://research.unc.edu/comparative-medicine/

2. North Carolina State University

a. https://cvm.ncsu.edu/research/departments/dphp/

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Haired skin: Trichofolliculomas,

multiple.

2. Oral mucosa: Squamous papillomas, multiple.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a concise review of the epizoology, associated lesions, and diagnosis of hamster polyoma virus (HaPyV), one of the first rodent polyomaviruses identified. HaPyV was discovered in the late 1960s in a colony of Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) affected by skin tumors. Ensuing research in Germany found viral particles extracted from the skin tumors caused lymphoma and leukemia when injected into neonatal hamsters.3 Research published by Barthold et al. in 1987 further evaluated its transmission, reporting the development of lymphoma in previously unexposed weanling hamsters that were subsequently maintained in both direct and indirect contact with hamsters previously exposed to HaPyV, which was known as hamster papovavirus at the time.1

A key feature of HaPyV is its ability to infect both undifferentiated keratinocytes as well as lymphocytes, resulting in the formation of hair follicle and lymphoid tumors. In addition, experimental HaPyV infection in Syrian hamsters has been reported to rarely induce sarcomas and mesothelioma. Mesothelioma is of particular interest in research given the risk of its development in humans following exposure to materials such as asbestos. Interestingly, HaPyV seems to only induce primary mesothelioma in female Syrian hamsters. In addition, transplanted mesotheliomas demonstrate accelerated tumor growth in females. The underlying cause of this sexual predilection is unknown.4

In addition to exposure of naïve hamsters to contaminated feces and/or urine, horizontal transmission of HaPyV may also occur due to fighting and/or grooming behavior. As noted by the contributor, subclinical animals, which are often older, may persistently shed the virus into the environment due to harboring it in the renal tubular epithelium. In regard to trichoepitheliomas, the viral infection induces the proliferation of follicular keratinocytes, particularly at the hair root epithelium. Viral particles are most concentrated in the stratum corneum and are absent in the proliferating cells of the stratum basale. In regard to lymphoma, large and immature neoplastic cells of B- or T-cell origin frequently invade local tissues and metastasis is common. Studies in transgenic mice have found HaPyV demonstrates a tropism for the spleen and thymus, evidenced by the preferential expression of HaPyV extrachromosomal DNA in these locations.4

Introduction of HaPyV to a colony can be detrimental, with mortality rates amongst young hamsters due to lymphoma reaching up to 80% within 4-30 weeks of exposure. There are no treatment options for HaPyV infection and culling affected animals is recommended.2,4 As noted by the contributor, once the virus becomes endemic the incidence of lymphoma decreases while trichoepithelioma increases, which is likely the result maternal antibody protection. Once enzootic, the virus cannot be controlled without the entire population being culled and the entire premises undergoing thorough decontamination. However, recurrent outbreaks have been reported following these extreme measures, likely due to the resistance of this virus to environmental decontamination.2

Detection of HaPyV virus particles via electron microscopy is a challenge. In addition, evaluation of HaPyV induced lymphoma with the intent of demonstrating viral particles is an ill advised endeavor since lymphoma induction occurs without viral replication. However, viral replication does occur within keratinizing epithelial cells of follicular tumors, often forming characteristic paracrystallin arrays within the nucleus.2 In addition to polyomaviruses, other viruses that form characteristic hexagonal paracrystallin arrays include adenovirus, papillomavurs, picornavirus, iridovirus, and circovirus.

Participants identified regions of sebaceous differentiation within the follicular neoplasms and therefore preferred the diagnosis of the trichofolliculoma rather than trichoepithelioma. Trichofolliculoma and trichoepithelioma are both characterized by differentiation to all three segments of the hair follicle, with the former exhibiting pilosebaceous subunits and/or more advanced trichogenesis whereas the latter may exhibit incomplete or abortive trichogenesis and a lack of sebaceous differentiation.

References:

1. Barthold SW, Bhatt PN, Johnson EA. Further evidence for papovavirus as the probable etiology of transmissible lymphoma of Syrian hamsters. Lab Anim Sci. 1987;37(3):283-288.

2. Barthold SW, Griffey SM, Percy DH. Pathology of laboratory rodents and rabbits. Fourth edition ed. Ames, Iowa, USA: Wiley Blackwell; 2016.

3. Fox JG, Anderson LC, Otto GM, Pritchett-Corning KR, Whary M, T. Laboratory animal medicine. Third edition ed. Amsterdam ; Boston ; Heidelberg ; London: Elsevier, Academic Press; 2015.

4. Jandrig B, Krause H, Zimmermann W, Vasiliunaite E, Gedvilaite A, Ulrich RG. Hamster Polyomavirus Research: Past, Present, and Future. Viruses. 2021;13(5):907.

5. Park C, Li S, Cha E, Schindler C. Immune response in Stat2 knockout mice. Immunity (Cambridge, Mass.). 2000;13(6):795-804.

6. Quesenberry K, Carpenter J. Ferrets, rabbits, and rodents. 3rd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012.

7. Scherneck S, Ulrich R, Feunteun J. The hamster polyomavirus?a brief review of recent knowledge. Virus Genes. 2001;22(1):93-101.

8. Simmons JH, Riley LK, Franklin CL, Besch-Williford CL. Hamster polyomavirus infection in a pet syrian hamster (mesocricetus auratus). Veterinary pathology. 2001;38(4):441-446.

9. Toth K, Lee SR, Ying B, et al. STAT2 knockout syrian hamsters support enhanced replication and pathogenicity of human adenovirus, revealing an important role of type I interferon response in viral control. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11(8).