CASE 3: S1601220 (4101207-00)

Signalment:

14-year-old, neutered male Quarter horse, Equus caballus

History:

The horse had a three-day history of progressive neurologic signs, fever ranging from 102 to 105°F, and icterus, and had been treated unsuccessfully with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prior to death.

Gross Pathology:

Full necropsy was performed approximately 6 hours after death. The carcass was in good nutritional condition with adequate internal fat reserves. Ocular sclera, fat [subcutaneous, pericardial, and abdominal], and articular surfaces [hip and shoulder] were icteric. Ecchymotic to suffusive hemorrhages were present in the ribcage (pleural, subpleural and intramuscular), along the ventral aspect of the vertebral column, multifocally in musculature, epicardium, endocardium, on serosal surfaces of most viscera, and in cerebral cortex. Heart contained deep red-black blood. Abdominal cavity contained approximately 5 liters of serosanguineous fluid with abundant fibrin that coated serosal surfaces of viscera and the peritoneal lining of the diaphragm. The liver was markedly enlarged, and the right and quadrate lobes were orange brown and friable. The left liver lobe was firm and deep red-black with numerous subcapsular and parenchymal emphysematous bullae. Cut surface had large, irregular pale foci surrounded by a hemorrhagic to black rim.

Meninges overlying brain and spinal cord were congested, and there were focal hemorrhages throughout the cerebral cortex. No lesions were seen in the rest of the carcass.

Laboratory results:

Liver impression smears processed by FAT were positive for Clostridium novyi, and negative for C. chauvoei, C. septicum and C. sordelli. Cultures were negative for C. perfringens, C. difficile and C. sordellii. Liver samples were positive for C. novyi type B fliC and TcnA genes, and negative for the fliC genes of the other clostridia tested.

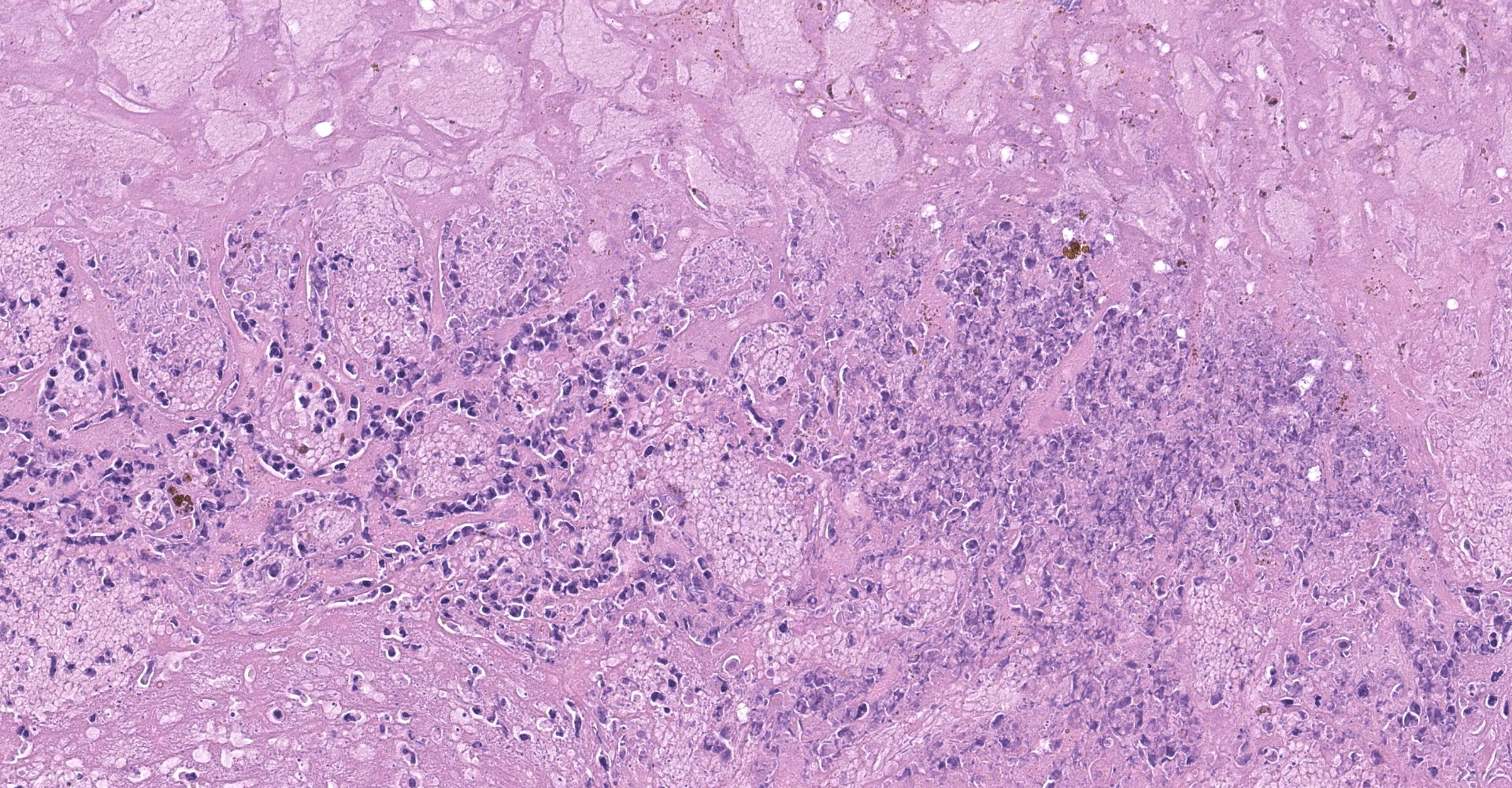

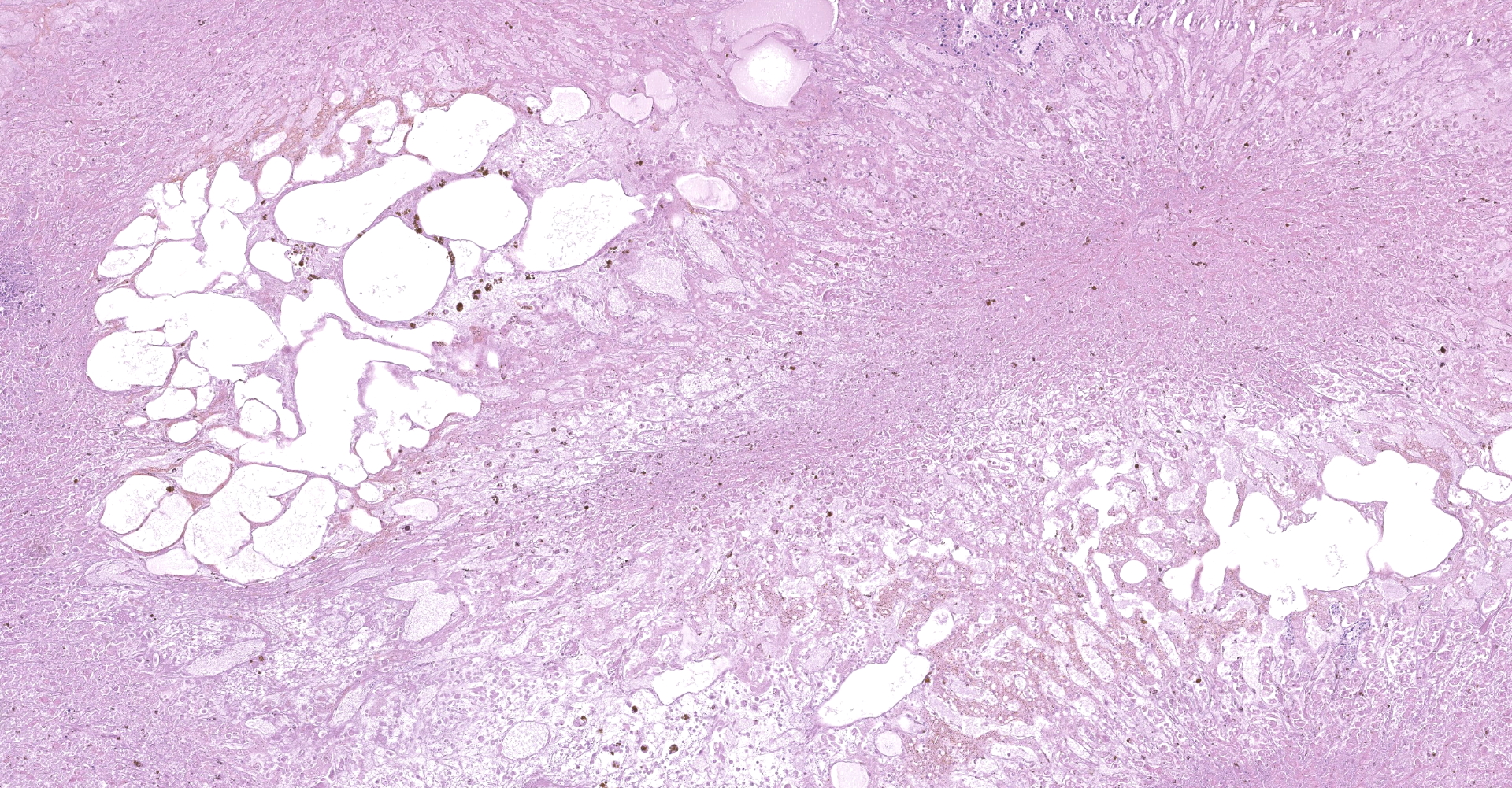

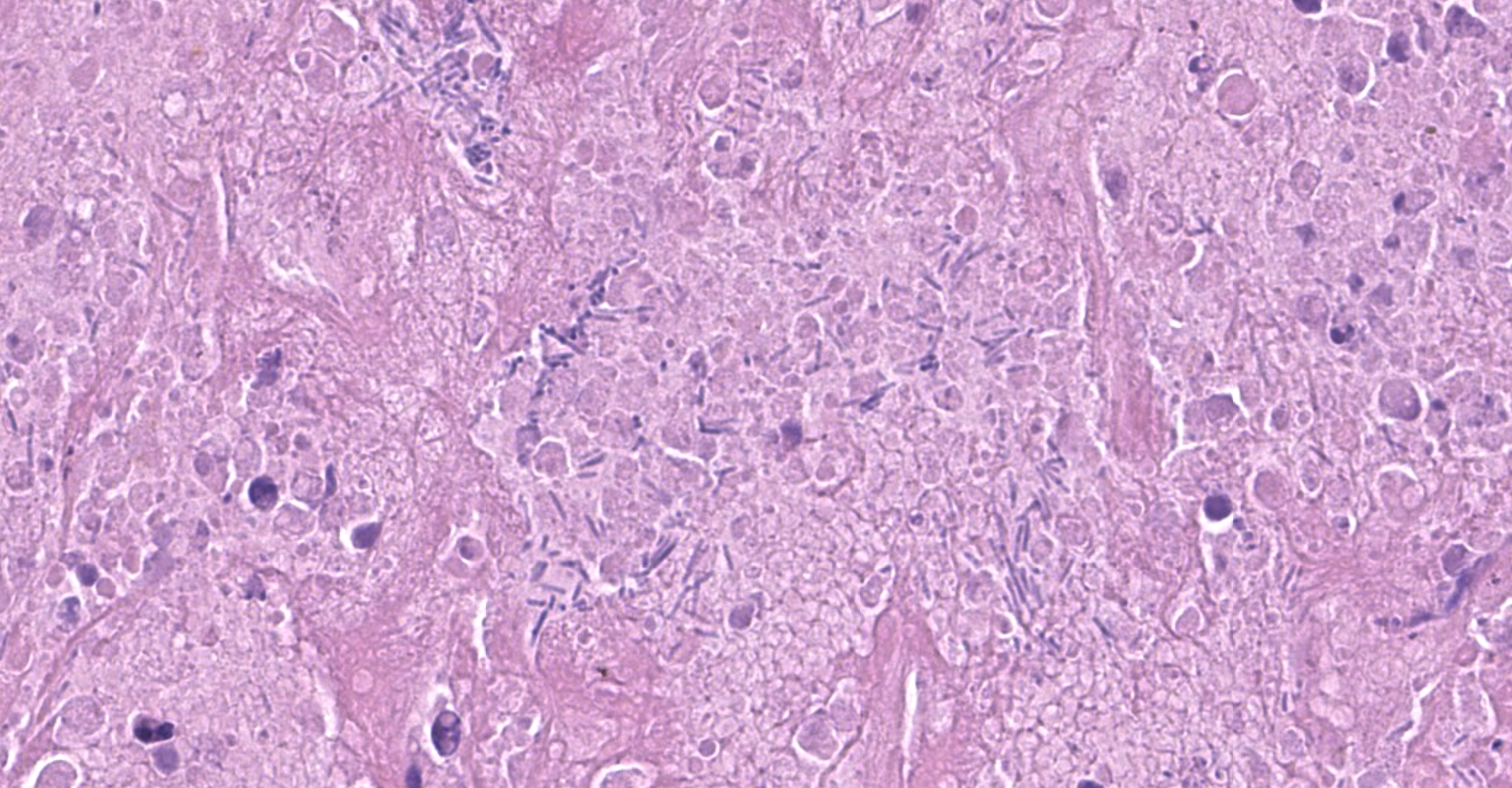

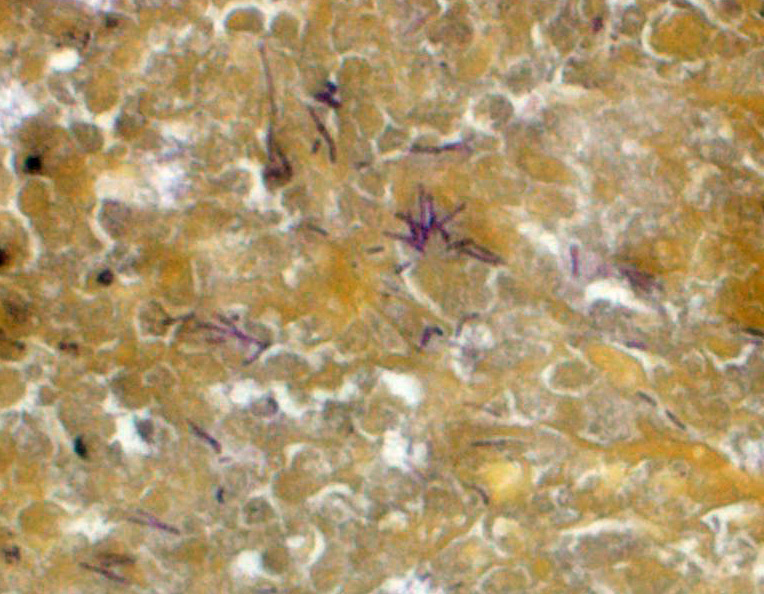

Microscopic description:

Liver: The hepatic capsule is multifocally lined by fibrin and cellular debris, and there are multiple, variably sized subcapsular and parenchymal emphysematous bullae. There is multifocal to focally extensive coagulative necrosis particularly of centrilobular to midzonal hepatocytes with frequent extension to involve entire lobules, accompanied by intralesional hemorrhage, fibrin, cellular debris, and large aggregates of gram-positive bacterial rods. Some of the bacteria had subterminal spores. Large numbers of viable and degenerate neutrophils border necrotic foci and are present in surrounding sinusoids. There is bile stasis, focal hemorrhages, vascular fibrinoid necrosis and thrombosis.

IHC: There was positive staining for C. novyi antigen.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, focally extensive to diffuse, severe, with cholestasis, emphysematous bullae, vascular fibrinoid necrosis and thrombosis, and intralesional gram-positive bacilli, etiology consistent with Clostridium novyi

Contributor's comment:

The presumptive diagnosis of infectious necrotic hepatitis [Clostridium novyi hepatitis] was made based on the typical gross and histologic findings, positive FA on liver impression smears, and positive staining for C. novyi antigen by IHC. Diagnosis was confirmed by PCR detection of the fliC and TcnA genes of C. novyi type B.8

Infectious necrotic hepatitis [black disease] is an acute lethal disease of ruminants and is rarely seen in horses and dogs.1,3,5,9 C. novyi is a gram-positive, spore-forming, anaerobic bacillus, which is commonly found in soil and feces of animals.9 It is classified into types A, B, and C based on the range of toxins produced.8 C. novyi type A produces mainly the lethal, edema-inducing alpha toxin (TcnA), and the non-lethal phospholipase, gamma toxin; this bacterium is associated with gas gangrene. C. novyi type B produces TcnA in addition to the necrotizing and hemolytic beta toxin. C. novyi type C is considered to be non-toxigenic and non-pathogenic. C. novyi type D is commonly known as C. haemolyticum and mainly produces beta toxin, the main virulence factor for bacillary hemoglobinuria in cattle.

It is speculated but not proven that the spores of C. novyi type B are absorbed from the intestine and reach the liver via the portal circulation, after which there is systemic dissemination. Spores are phagocytized and remain latent in Kupffer cells of the liver, and in macrophages of the spleen and bone marrow.3,4 Both infectious necrotic hepatitis [INH] and bacillary hemoglobinuria [BH] are thought to occur after liver injury causing necrosis and the associated anaerobic conditions that are required for germination of latent spores and the production of toxins.5 Among causes of hepatic injury, migration of immature forms of Fasciola hepatica through the liver is considered the most important predisposing factor for both BH and INH in ruminants, and both diseases are more common in areas with high prevalence of fascioliasis.3 No predisposing factors were identified in the equine case presented here.

Contributing Institution:

California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory

University of California Davis, San Bernardino Branch

105 W. Central Ave., San Bernardino, CA 92408

www.cahfs.ucdavis.edu

JPC diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, diffuse, severe, with thrombosis, emphysema, and numerous spore-forming bacilli.

JPC comment:

The contributor provides a concise summary and subsequently published this case report in 2018.7 This is an uncommon disease in horses, and at the time of this writing, only seven cases of equine infectious necrotizing hepatitis have been reported. Sheep are most often affected by infectious necrotizing hepatitis, but as in this case, other species are affected as well. While the most important toxins were detailed by the contributor, the production of TcnA is related to phage infection of the bacterium.6 When Clostridium novyi type A or type D were cured of phages NA1tox+ and NB1tox+, respectively, they no longer produced alpha toxin. Re-infection resulted in the renewed ability to produce alpha toxin.2 While this was published in 1976 and there is not a current effort to improve medical treatment by targeting bacteriophages, as technology improves, it may enjoy renewed research.

When latent spores experience a low oxygen microenvironment, they begin to elaborate TcnA and beta toxin. TcnA enters host cells by means of receptor mediated endocytosis using a currently unidentified membrane receptor. Acidification within the endocytic vesicle allows cleavage of the N-terminal domain and the toxin's movement into the cytosol. Rho- and/or Ras-GTPases from UDP-N-acetylglucosamine are glucosylated by the active form of TcnA. This results in disruption of the actin cytoskeleton, and minor disruption to the vimentin and microtubule systems. While beta toxin is also capable of causing hepatic necrosis, such small quantities are produced that it is unlikely to play a significant role in pathogenesis.6

Other Clostridium spp also cause significant liver disease, in a wide variety of animals. As discussed, C. haemolyticum was previously known as C. novyi type D and is the cause of bacillary hemoglobinuria in ruminants (and rarely horses) through large quantities of beta toxin. C. piliforme is the only gram negative, obligate intracellular clostridia, and is the cause of Tyzzer's Disease in foals, laboratory rodents, and other lagomorphs.6 Unfortunately, the virulence factors for C. piliforme have yet to be identified.

References:

1. Cullen JM, Stalker ML. Necrotic hepatitis (black disease). In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2016:316.

2. Eklund, MW, Poysky FT, Peterson ME, Meyers JA. Relationship of bacteriophages to alpha toxin production in Clostridium novyi types A and B. Infection and Immunity. 1976;14(3):793-803.

3. Gay CC, Lording PM, McNeil P. Infectious necrotic hepatitis (black disease) in a horse. Equine Vet J 1980;12[1]:26?27.

4. Nakamura S, Kimura I, Yamakawa K. Taxonomic relationships among Clostridium novyi type A and B, Clostridium haemolyticum and Clostridium botulinum type C. J Gen Microbiol 1983;129[5]:1473-1479.

5. Navarro M, Uzal FA. Infectious necrotic hepatitis. In: Uzal FA, et al., eds. Clostridial Diseases of Animals. 1st ed. Ames, IA: Wiley Blackwell, 2016:275?279.

6. Navarro MA, Uzal FA. Pathobiology and diagnosis of clostridial hepatitis in animals. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2020;32(2):192-202.

7. Nyaoke AC, Navarro MA, Beingesser J, Uzal FA. Infectious necrotic hepatitis caused by Clostridium novyi type B in a horse: case report and review of the literature. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2018;30(2):294-299.

8. Sasaki Y, Kojima A, Aoki H. Phylogenetic analysis and PCR detection of Clostridium chauvoei, Clostridium haemolyticum, Clostridium novyi types A and B, and Clostridium septicum based on the flagellin gene. Vet Microbiol 2002;86[3]:257-267.

9. Sweeney HJ, Greig A. Infectious necrotic hepatitis in a horse. Equine Vet J 1986;18[2]:150?151.