Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 20

April 6th, 2018

CASE II: 20327-15 A or C (JPC 4099033).

Signalment: 2-year-old male neutered Cocker spaniel (Canis familiaris), canine.

History: In the 6-months prior to death, the dog had periodic bouts of inappetence, dark stools, and jaundice. The submitting veterinarian performed a necropsy and submitted formalin-fixed liver to ALPC for examination.

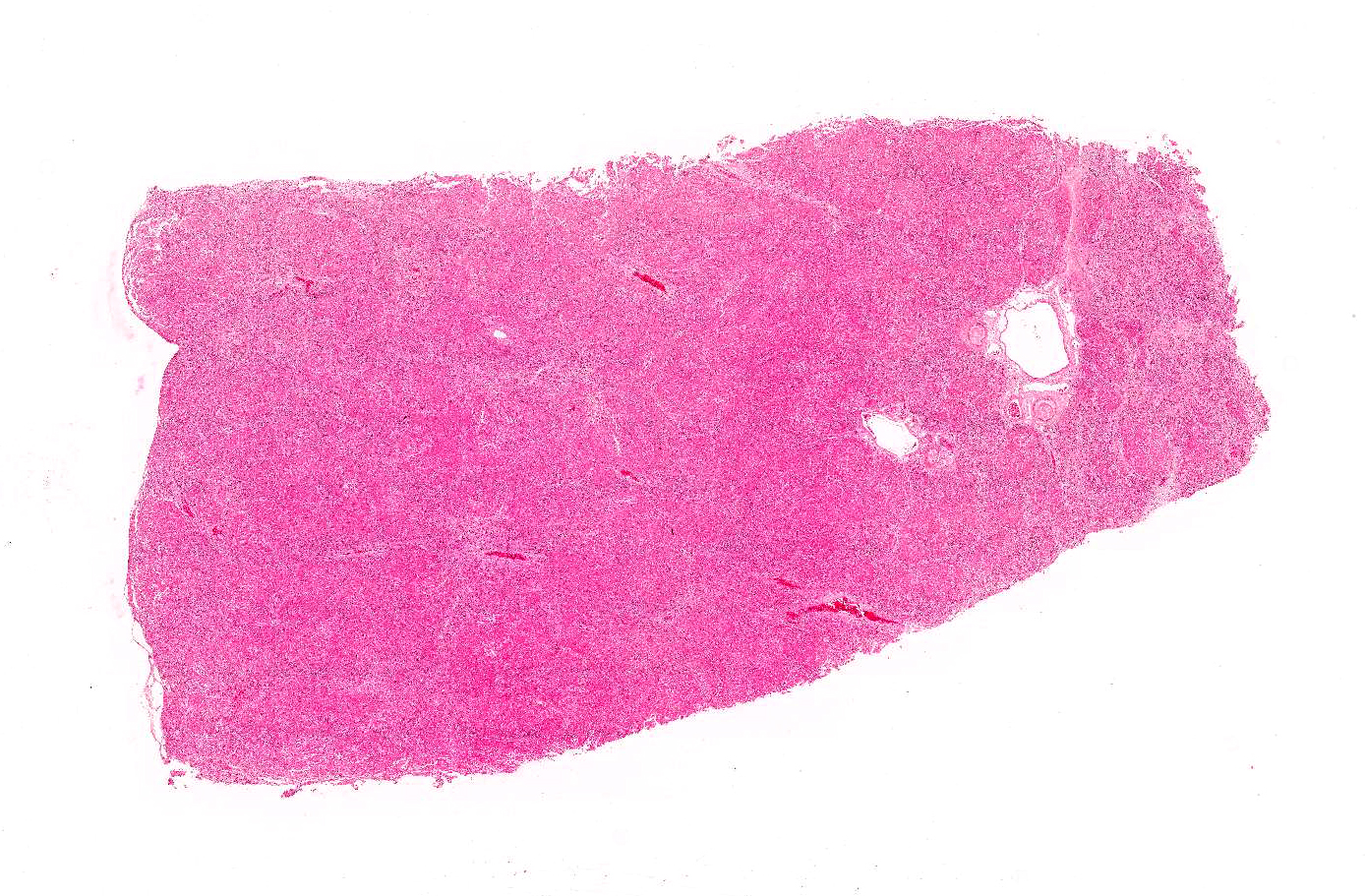

Gross Pathology: Liver: Small and firm with numerous 1-2 mm, nodules throughout the surface.

Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.):

ALT 168 (12-118 U/L)

ALP 172 (5-131 U/L)

Total Bilirubin 2.4 (0.1-0.3 mg/dL)

Albumin 1.6 (2.7-4.4 g/dL)

BUN 4 (6-31 mg/dL)

Urine bilirubin 3+

Bile acids pre-meal: 18.8 (<10.0 umol/L)

Bile aids post-meal: 21.8 (<20.0 umol/L)

Leptospirosis titers: Negative

Copper: 1460.0 ppm (dry weight)

Measurement was performed on formalin-fixed tissue.

COPPER DIAGNOSTIC LEVEL: Canine: Liver (DW) – normal 120-400 ppm; deficient < 80 ppm; toxic > 1,500 ppm.

**Several profiles were run throughout the 6-month duration of the illness. The most significant of these results are listed above.

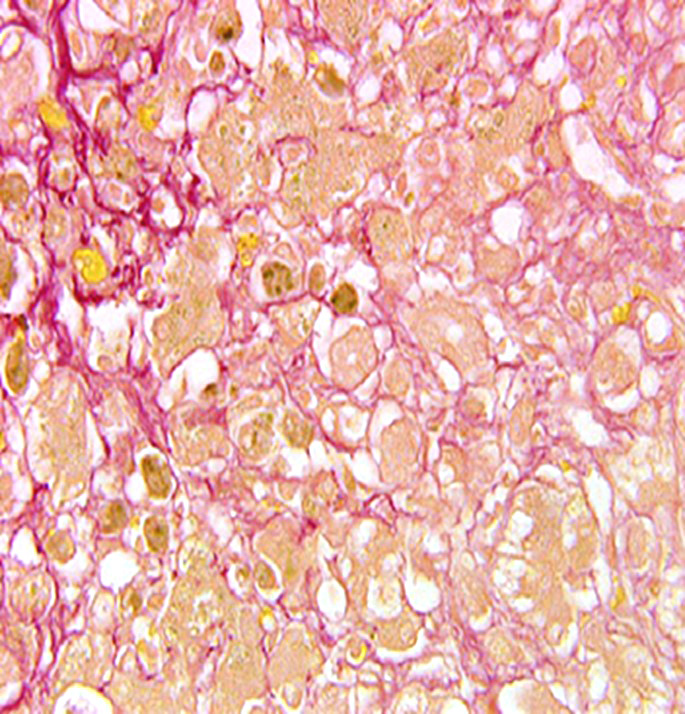

Microscopic Description:

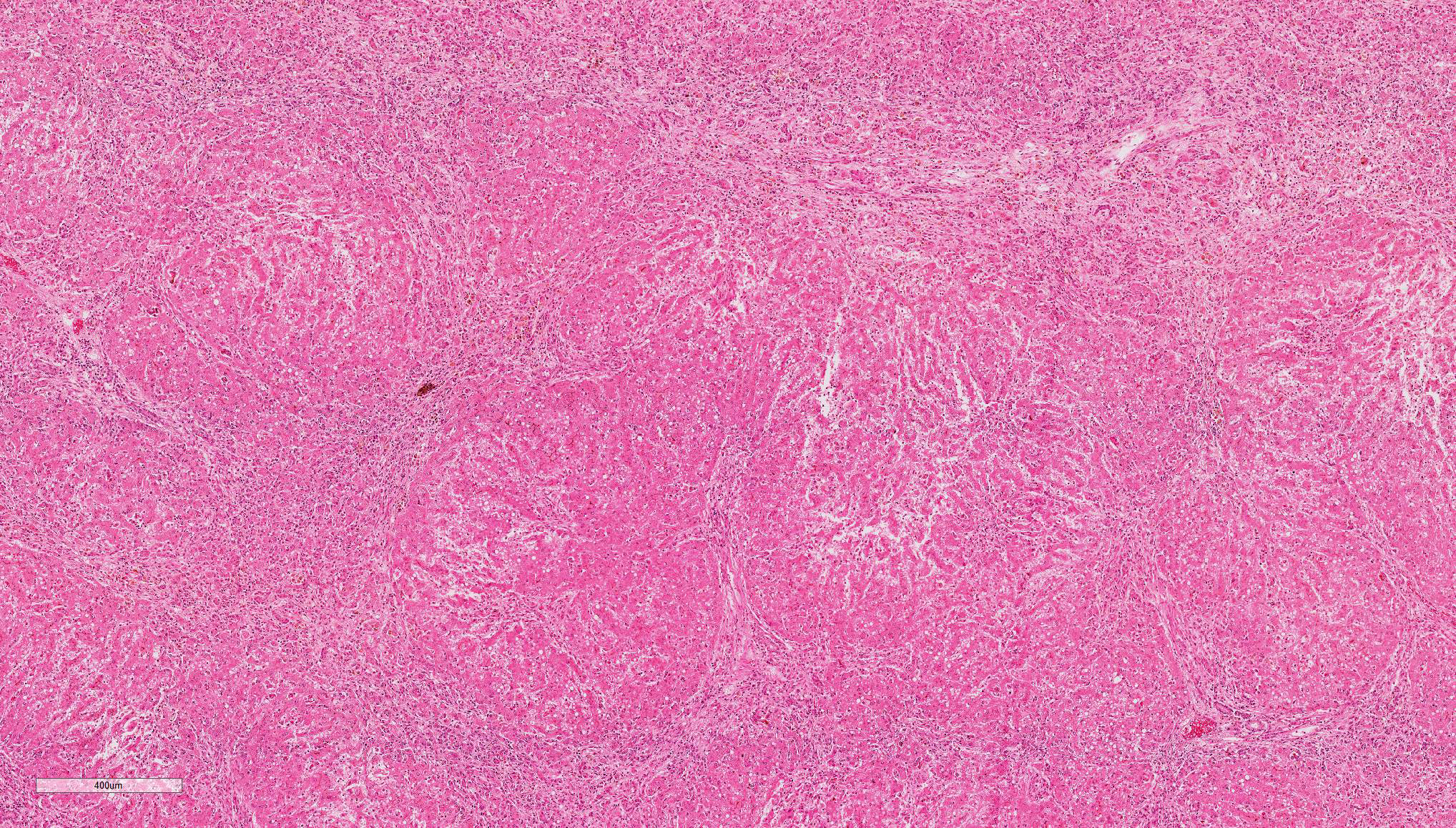

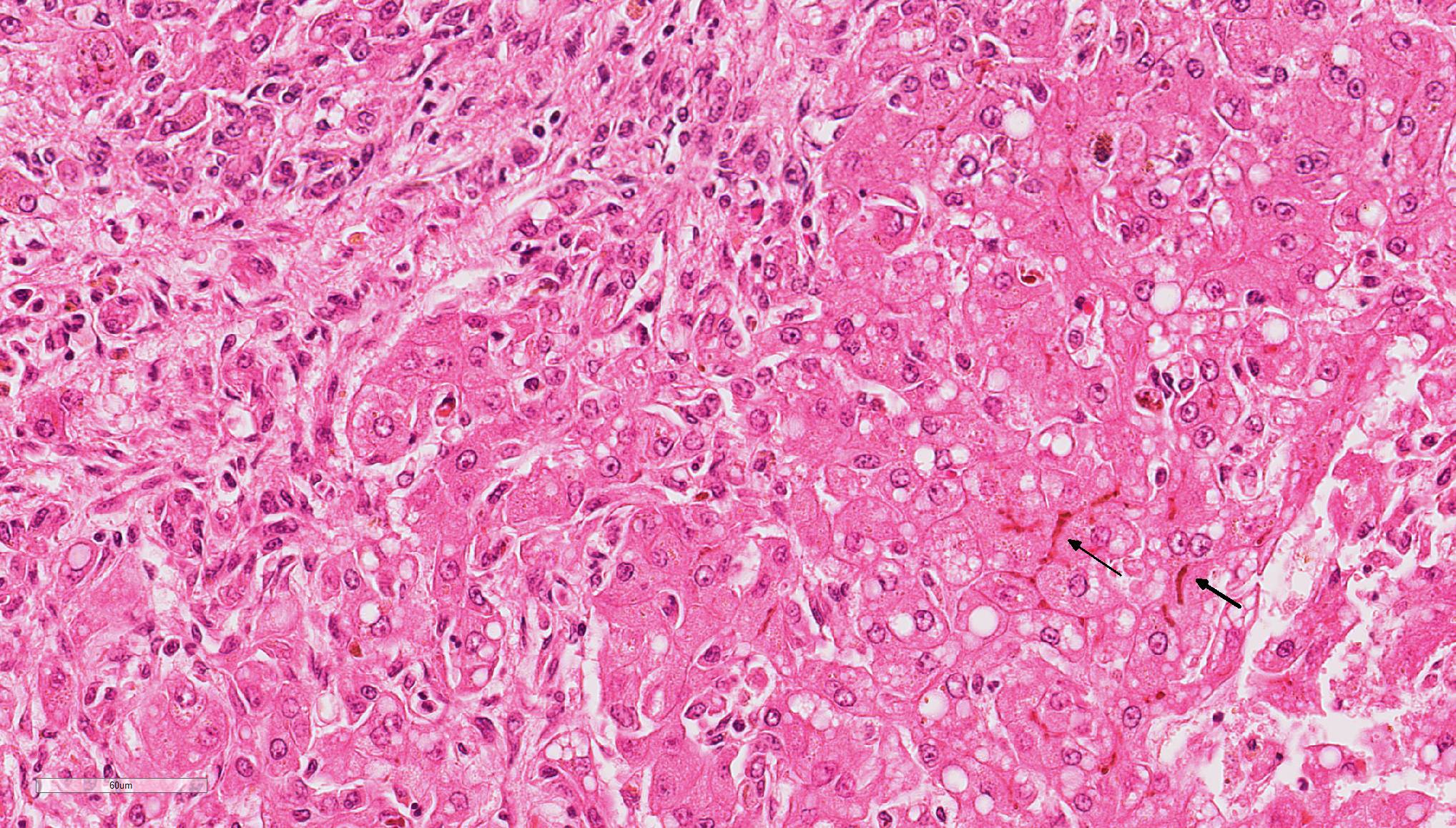

Liver: Diffusely, the normal hepatic architecture is replaced by numerous regenerative nodules that are up to 3.5 mm in diameter. Regenerative nodules are separated and surrounded by bridging tracts of fibrous connective tissue. Fibrous tracts contain a moderate proliferation of bile ducts and/or oval cells that are frequently mixed with individual or small clusters of hepatocytes. Small numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells, few macrophages, and rare neutrophils are also multifocally scattered throughout fibrous tracts. Diffusely, there is marked loss of portal triads with few recognizable portal triads remaining within fibrous tracts. Bile canaliculi throughout the regenerative nodules are frequently expanded with bile. Multifocally, hepatocytes and Kupffer cells within nodules and fibrous tracts contain small to moderate amounts of yellow-gold to gold-brown pigment. Small to moderate numbers of hepatocytes within regenerative nodules and fibrous tracts exhibit macrovesicular vacuolation, characterized by single or small numbers of discrete, clear, intracytoplasmic vacuoles. Occasionally, portal veins and lymphatics are markedly dilated, and occasionally, sinusoids exhibit mild congestion.

HALLS BILE: Bile canaliculi, hepatocytes, and Kupffer cells within regenerative nodules and to a lesser extent fibrous tracts are often distended with bile pigment.

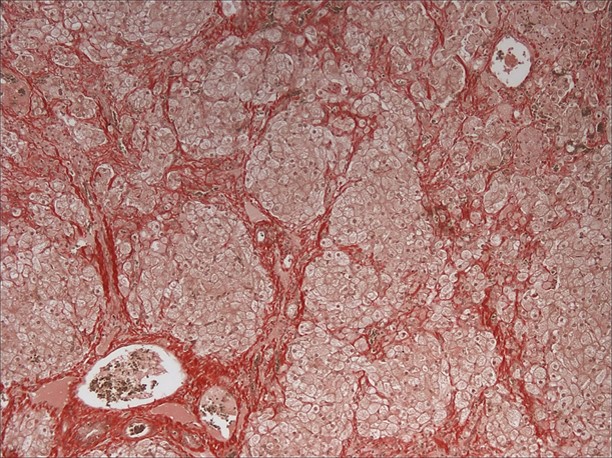

RHODANINE: Frequently, hepatocytes and Kupffer cells within regenerative nodules and fibrous tracts contain small to moderate amounts of copper.

MASSON'S TRICHROME: Diffusely, delicate strands of collagen separate and surround individualized hepatocytes and hepatocyte clusters within fibrous tracts.

PRUSSIAN BLUE: Small numbers of Kupffer cells scattered throughout regenerative nodules and the fibrous tracts contain small to moderate amounts of iron pigment.

GOMORI'S RETICULIN: Diffusely, the normal lobular architecture is lost within both the regenerative nodules and the fibrous tracts. Reticulin fibers within the fibrous tracts are more numerous than the reticulin fibers within regenerative nodules and are also haphazardly arranged. Reticulin fibers within the fibrous tracts often separate and surround collagen bundles and dissect between or completely surround individual and small groups of hepatocytes and/or inflammatory cells.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Multifocal, widespread lobular dissecting hepatitis with marked fibrosis; mild, mixed inflammation; diffuse micronodular regeneration; moderate cholestasis; and occasional lymphatic ectasia

Contributor’s Comment: The arrangement of the reticulin fibers within fibrous tracts indicates lobular dissection of the parenchyma. The lobular dissection and the proliferation of bile ducts within fibrous tracts is compatible with a diagnosis of lobular dissecting hepatitis, a form of cirrhosis most often seen in young adult dogs.2,3,5,6 This form of chronic hepatitis has recently been reported in the American Cocker Spaniel.3 Cocker Spaniels are at increased risk for early onset chronic hepatitis that quickly becomes cirrhotic. Males are preferentially affected, and most of these dogs are diagnosed as young adults.6 Disease is typically advanced at presentation, and most of these dogs lack signs of liver disease prior to the development of portal hypertension and ascites, the most common presenting sign.3,6 Since disease is typically advanced at presentation, most dogs die within a few months of diagnosis.6 In addition to cirrhosis, the condition is characterized by marked bile duct proliferation, a mild necroinflammatory response, and inconsistent copper retention.2,3,5,6 Hepatic copper retention may occur as a primary injury or secondary to cholestasis. Since copper retention is inconsistent in this condition, most cases are attributed to cholestasis (which was prominent in this case).2,6 The cause of chronic hepatitis in the Cocker Spaniel remains unknown. Because of the breed association, a genetic component has been postulated, and an α1-antitrypsin deficiency has been suggested, but remains unproven.2,3,6

JPC Diagnosis: Liver: Bridging fibrosis, diffuse, severe with marked micronodular hepatocellular regeneration, biliary hyperplasia, cholestasis, and diffuse hepatocellular lipidosis, Cocker spaniel (Canis familiaris), canine.

Conference Comment: Chronic hepatitis has frequently been reported in English and American Cocker Spaniels and English Springer Spaniels. Recently, American Cocker Spaniels have been reported to have lobular dissecting hepatitis, a distinct pattern of chronic hepatitis which has been most frequently identified in young dogs with ascites and acquired portosystemic shunts resulting from portal hypertension. Grossly, these two conditions have distinct differences. Chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis appears grossly as small, firm livers with multiple regenerative nodules, whereas, in lobular dissecting hepatitis, the liver is also small and pale with fewer hyperplastic nodules.1

Microscopically, there is also variation in pattern between these two conditions. Chronic hepatitis is characterized by moderate to severe portal hepatitis with inflammatory infiltrates (lymphocytes, plasma cells and fewer neutrophils) and variable degrees of portal and bridging fibrosis. Lobular dissecting hepatitis, on the other hand, is characterized by dissection of hepatic parenchyma by reticulin and fine collagen fibers, subdividing individualized and small groups of hepatocytes. Fibroblasts, suspected of hepatic stellate origin, are prominent along sinusoids. Regenerative nodules may also be present, but not as consistently as with chronic hepatitis. In contrast with chronic hepatitis, portal inflammation and periportal fibrosis is not a prominent feature in lobular dissecting hepatitis.1

As mentioned by the contributor above, α1-antitrypsin deficiency has been suggested to play a role in English Cocker Spaniels. α1-antitrypsin, a plasma glycoprotein, is a member of the serine proteinase inhibitor superfamily, and an inhibitor of neutrophil elastase. In humans, α1-antitrypsin deficiency leads to misfolded forms of α1-antitrypsin which accumulate in the rough endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes and form PAS-positive globules. The damage of hepatocytes resulting from accumulation of this protein has been associated with neonatal hepatitis, juvenile cirrhosis, and adult hepatocellular carcinoma in humans.1

A recent study of this condition identified the spindle cells producing reticulin and collagen fibers as myofibroblasts, as a result of their immunopositivity for anti-α-smooth muscle actin and anti-vimentin antibodies. Additionally, the reticular fibers produced by these cells were strongly positive for anti-collagen type III and type IV antibodies with positivity to anti-fibronectin and anti-laminin antibodies continuously along the basement membrane of the sinusoids of remaining hepatic cords and in between hepatocytes. This study also suggests that expression of fibronectin and laminin occurs before the deposition of reticulin between hepatocytes indicating an active extracellular matrix which contributes to the architectural damage.4

During the conference, the moderator reviewed patterns of cholestasis, observing that extrahepatic obstruction leads to circumferential fibrosis around bile ducts and biliary hyperplasia. The cholestasis in this case is likely due to fibrosis (intrahepatic obstruction) within the liver.

Conference attendees reviewed a case report3 about American cocker spaniels with lobular dissecting hepatitis and noted that those dogs frequently have ascites that does not affect them as rapidly as other dogs with chronic hepatitis. Additionally, this report subdivides lobular dissecting hepatitis. According to this particular classification, the moderator believes that this particular casecase would fall in the subcategory of bridging fibrosis or micronodular cirrhosis. One unusual finding was the moderate amount of copper present in this case, whereas the dogs in the case study did not have any copper accumulation.

Contributing Institution:

http://www.aad.arkansas.gov/veterinary-diagnostic-lab

References:

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:302-305.

- Kahn CM, Line S, et al. The Merck Veterinary Manual. 10th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc.; 2010:423-428.

- Kanemoto H, Sakai M, Sakamoto Y, Spee B, Van den Ingh TSGAM, Schotanus BA, Ohno K, Rothuizen J. American cocker spaniel chronic hepatitis in Japan. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27:1041-1048.

- Mizooku H, Kagawa Y, Matsuda K, Okamoto M, Taniyama H. Histological and immunohistochemical evaluations of lobular dissecting hepatitis in American cocker spaniel dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 2013; 75(5):597-603.

- Van den Ingh TSGAM, Van Winkle TJ, Cullen JM, et al. Morphological classification of parenchymal disorders of the canine and feline liver. In: Rodenhuis J, ed. WSAVA Standards for Clinical and Histological Diagnosis of Canine and Feline Liver Diseases. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2006:94-98.

- Willard MD. Inflammatory canine hepatic disease. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2010:1637-1642.