Signalment:

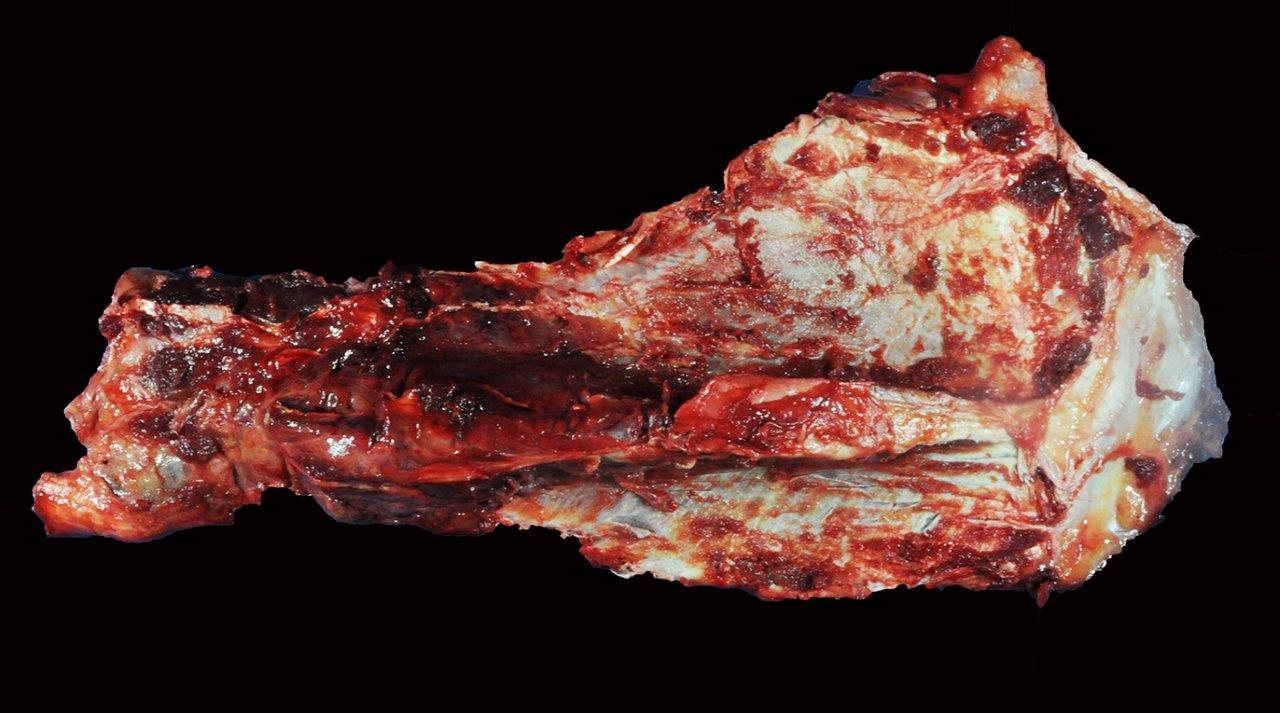

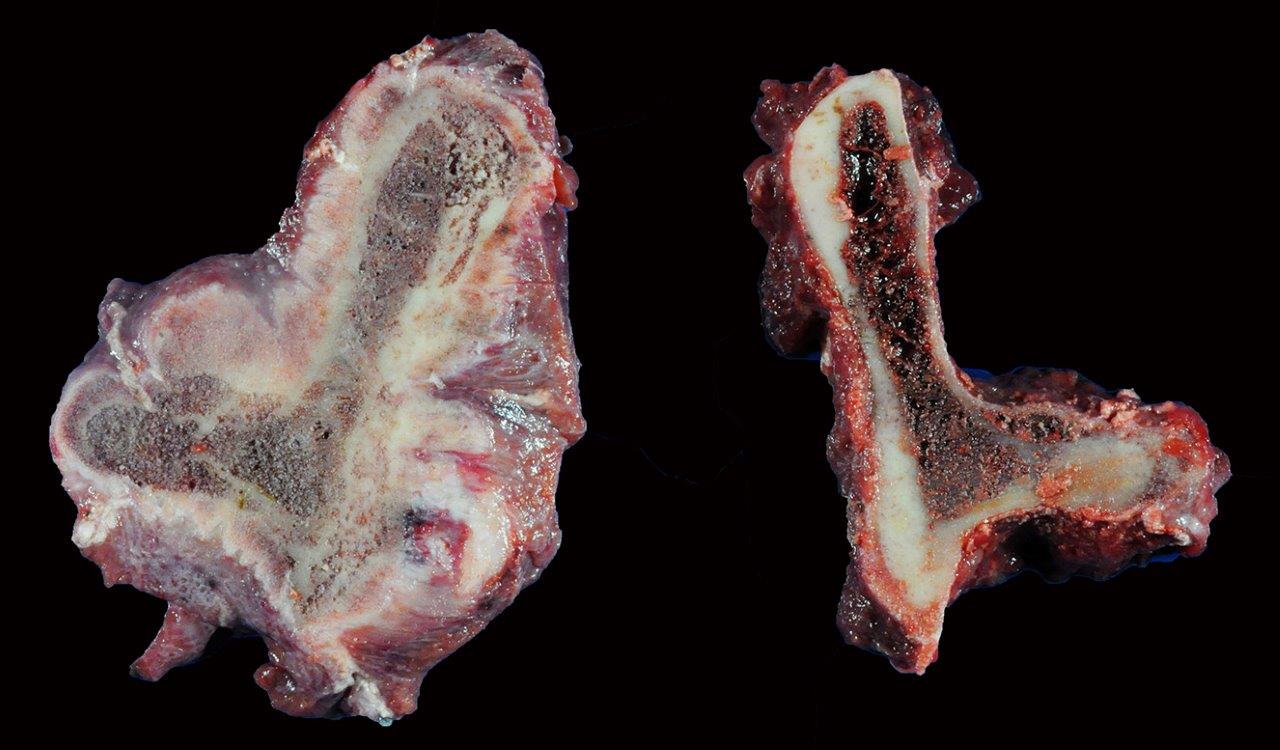

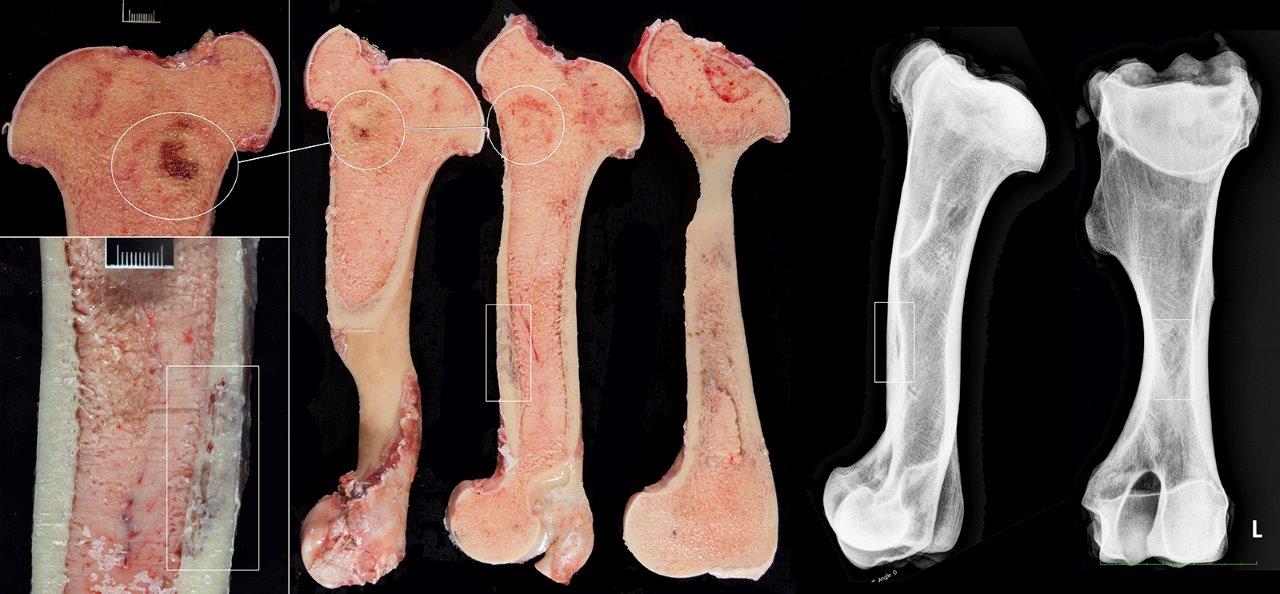

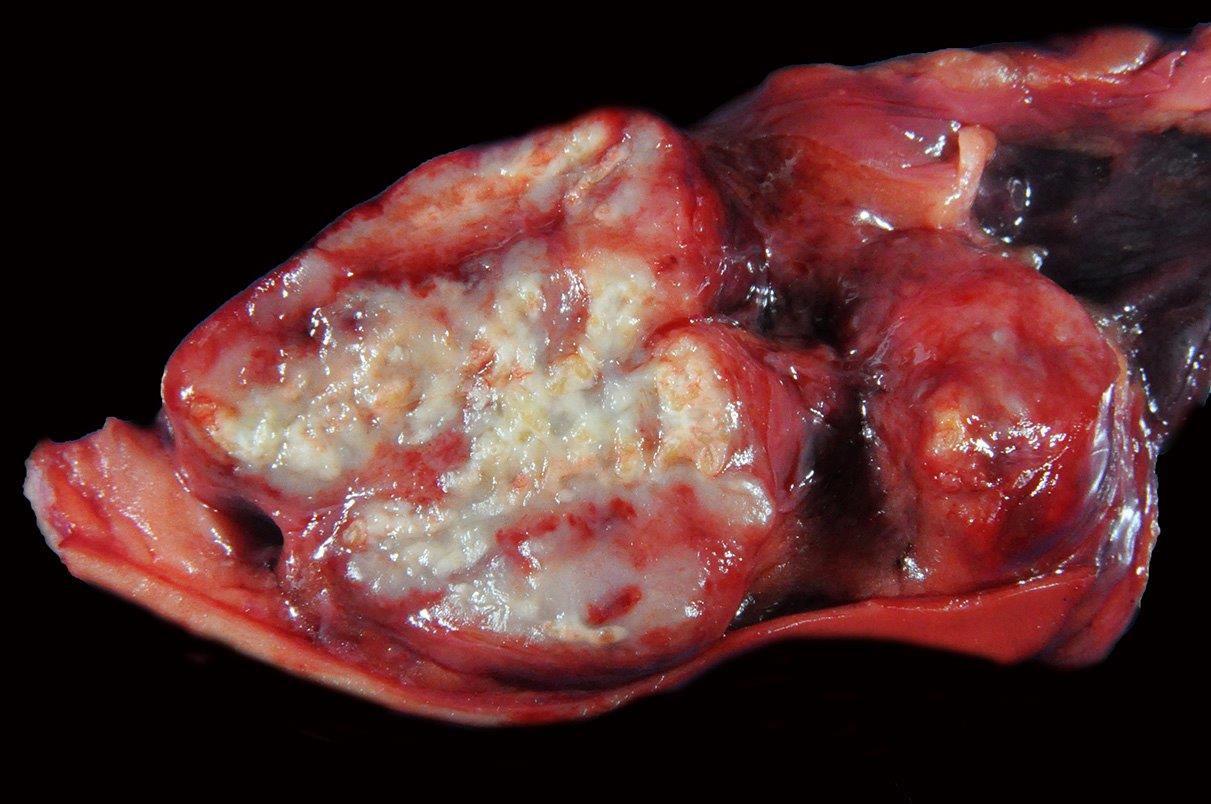

Gross Description:

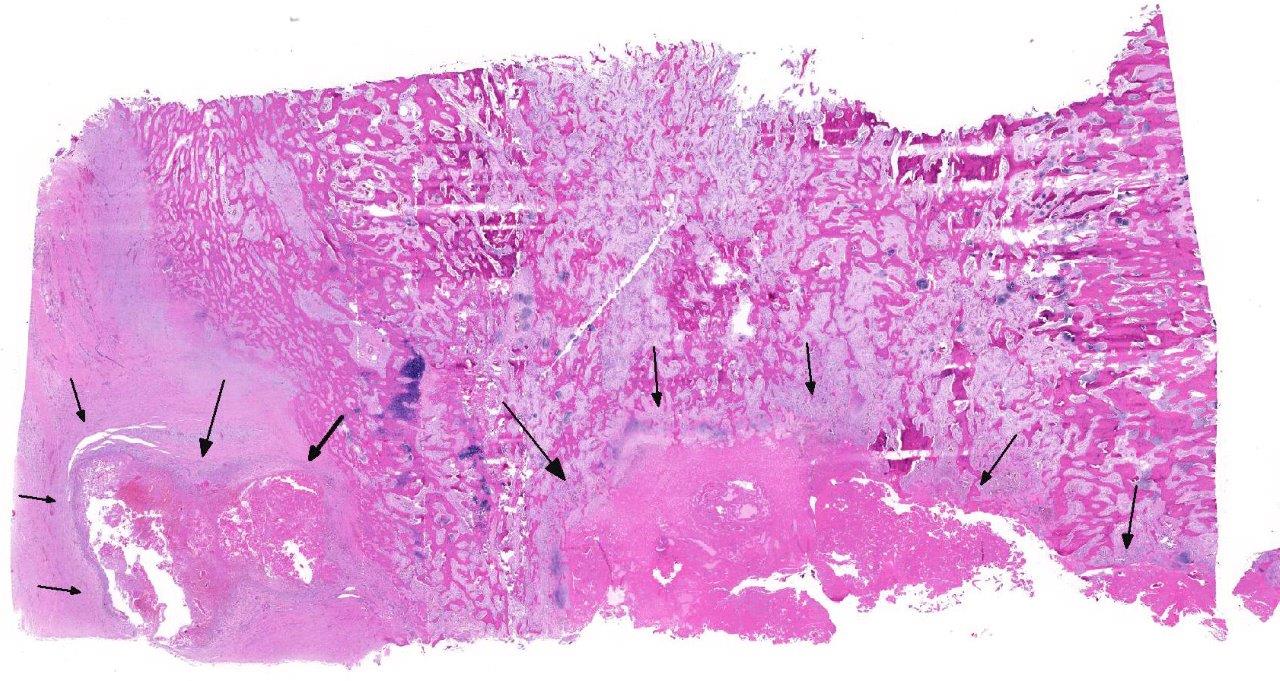

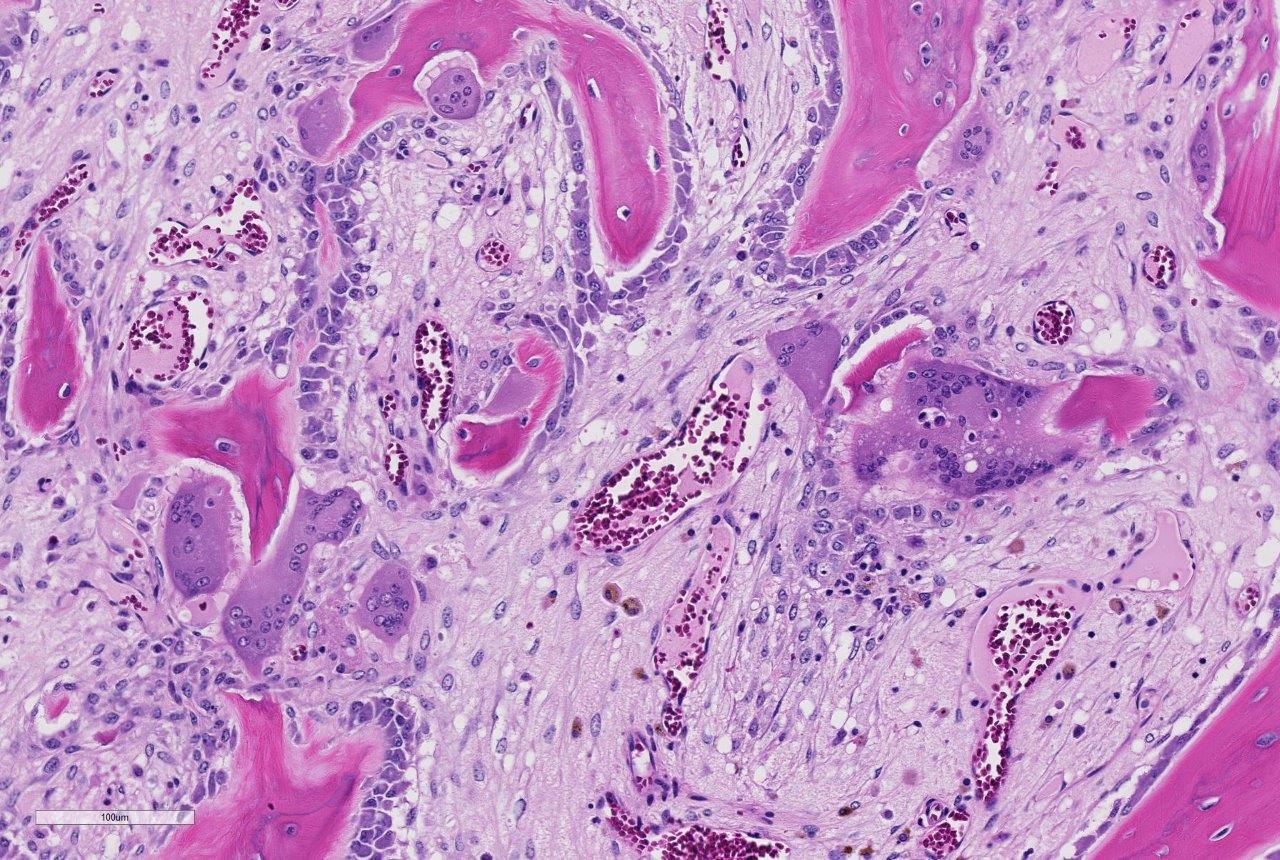

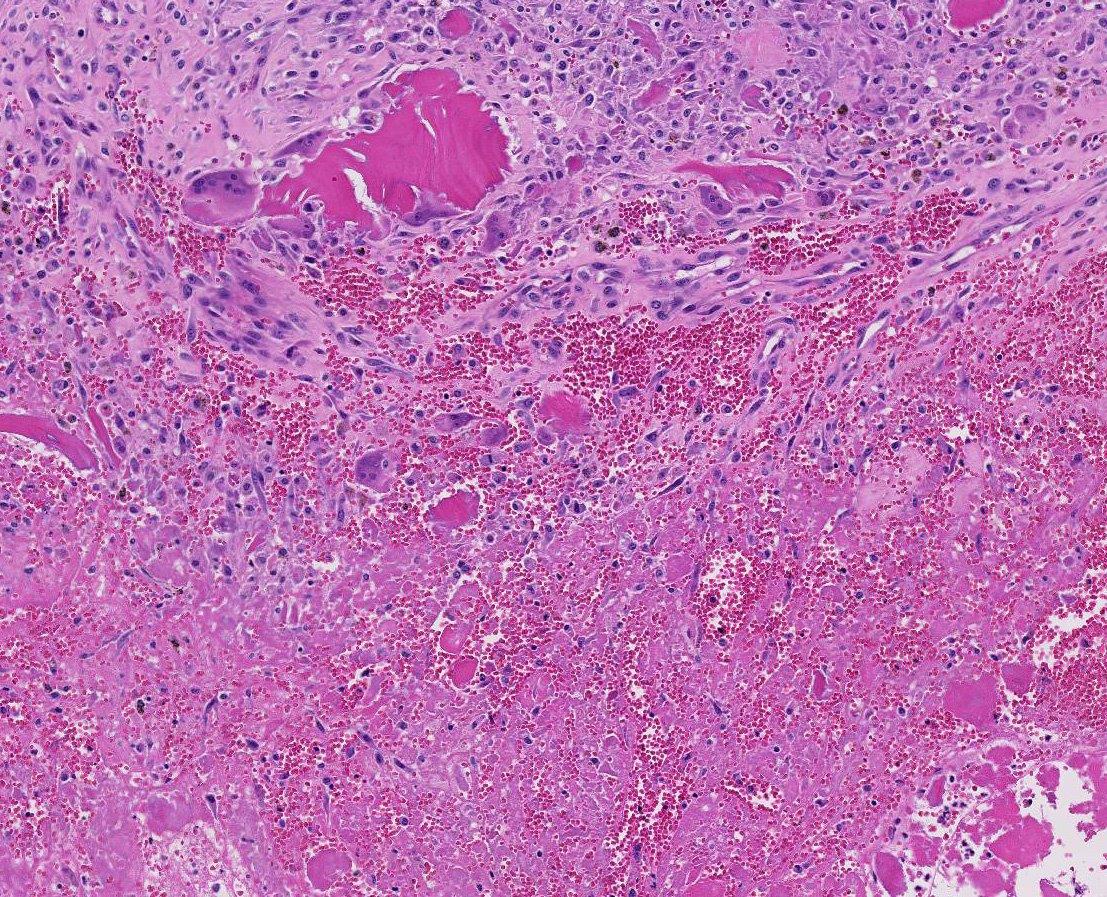

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Mild increase in creatinine kinase 348 IU/L (119-287)

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Pulmonary silicosis has been previously reported in both humans and horses, however, the associated osteoporotic syndrome appears unique to equids.1 The underlying pathogenesis for this condition has yet to be elucidated. Affected horses present with vague acute or chronic signs of lameness, often accompanied by weight loss, and variably by clinically evident pulmonary disease. Horses may appear to have bowing of one or both scapulae and accentuated lordosis. Acute lameness may be observed secondary to pathologic fractures often with ineffective attempts at repair as observed in this case. If clinically silent, chronic fibrosing granulomas within the lung-draining lymph nodes and variably within the lungs are usually identified postmortem. Thoracic radiographs may detect an interstitial pattern of consolidated pulmonary nodules, but will often miss mineralized, lung-associated lymph nodes. Histologic examination of the granulomas reveals the typical pattern of central necrosis, marked fibrosis and mineralization surrounded by epithelioid macrophages and occasional giant cells. Small, angular, birefringent, intra- and extra-cellular crystals may be revealed under polarized light. The exorbitant reaction associated with such crystals is unique to the toxicity of cristobalite as compared to relatively innocuous accumulations associated with common anthracosilicotic nodules. Electron diffraction crystallography has been used to confirm the physical characteristics of crystals as cristobalite, (technique available in geology laboratories that analyze soil or stones).

Clinical and postmortem radiographs of the axilla and proximal appendicular skeleton are non-specific but may reveal poorly demarcated areas of osteoporosis and confirm bone deformity. Finding cervical facet joint osteoarthrosis is common in advanced cases of SAO. The radiographic appearance of bone lesions is variable but can be mistaken for neoplasia driven osteolysis as observed in this case. Currently, the most sensitivity pre-mortem diagnostic test for this condition is bone nuclear scintigraphy.4 The search for sensitive and specific clinical markers to detect early onset of the disease is ongoing.

Histologic examination of the affected bone reveals dysregulated resorption by morpho-logically atypical giant hyperactive osteoclasts.1 Typical of SAO, the osteoclasts indiscriminately resorb pre-existing cortical and trabecular bone as well as newly formed woven bone. A mosaic pattern of cement lines is commonly observed in SAO bones; this microscopic feature is shared by human Paget disease of bone.6 Multifocal areas of bony lysis, aberrantly increased regions of bone remodeling, pathologic fractures and aberrant giant osteoclasts are other similarities observed between these two disorders.1 However, polyostotic Paget disease is restricted to specific age groups (elderly humans) and exhibits cessation of osteoclast activity over time. In contrast, SAO is observed in horses of all ages and shows progression of disease with time.1,5 In addition, the skeletal distribution of SAO does not correspond with that observed in Paget disease.1 The lesions of SAO have also been compared to fibrous osteo-dystrophy, however, skull lesions are uncommon in horses with SAO and only a subset of affected horses exhibit elevations in parathyroid hormone.1

Unusual features of this case include the effacement of hematopoietic tissue within the medullary cavity and the identification of gross and radiographic lesions with the humeri.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The pathogenesis and cause of bone fragility syndrome in horses is unknown. The vast majority of affected horses present concurrently with pulmonary silicosis and there is likely a causal relationship between the two conditions. As mentioned by the contributor, pulmonary silicosis, defined as silicate pneumoconiosis with accompanying pulmonary fibrosis, occurs secondary to inhalation of cytotoxic silica dioxide (SiO2) crystal polymorphs, including quartz, cristobalite, and tridymite.1,2,3 Pulmonary silicosis with concurrent bone fragility syndrome has been reported with increased frequency in horses from areas with high levels of soil cristobalite, such as Monterey, Napa, and Sonoma regions of California; however, affected horses have also been seen in Oregon, Texas, Virginia, Illinois, and Kentucky.1,2,3 The cytotoxic crystals associated with pulmonary silicosis are found worldwide, perhaps suggesting that this disease may be more widespread.1,2

Readers are encouraged to review 2015 Wednesday Slide Conference #3 Case 4 for an excellent review of a suspected case of pulmonary silicosis in a horse from Monterey, California. It is thought that the inhaled silicate stimulates the massive release of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-alpha, which stimulate inflammation and osteoclastogenesis via increased production of the RANKL and decrease in expression of the decoy receptor, osteo-protegerin.1 Other proposed mechanisms of pathogenesis include hyperparathyroidism or an equine variant of Paget disease of bone in humans.1,2

Horses with bone fragility usually present with chronic lameness and skeletal deformities such as lateral bowing of the scapulae, lateral bowing of the rib cage, lordosis, and decreased range of motion in the cervical vertebrae.1,2 Bones of both the axial and proximal portions of the appendicular skeleton, such as the scapula, in this case, are typically affected. Radio-graphically, there is severe osteopenia with multiple bony lucencies and exostoses at the articular facets as well as thickening of the rib consistent with extensive bone remodeling.1,2 As a result of the severe osteoporosis associated with this disease entity, most animals die from a catastrophic pathologic fracture.1,2 Conference participants noted that the large focally extensive area of necrosis in this tissue section may be the site of a pathologic fracture of the scapula.

References:

- Arens AM, Barr B, Puchalski SM, et al. Osteoporosis associated with pulmonary silicosis in an equine bone fragility syndrome. Vet Pathol. 2011; 48(3):593-615.

- Arens AM, Puchalski SM, Whitcomb MB, et al. Comparison of the use of scapular ultrasonography, physical examination, and measurement of serum biomarkers of bone turnover versus scintigraphy for detection of bone fragility syndrome in horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013; 242(1):76-85.

- Berry CF, OBrien TR, Madigan J, Hager DA. Thoracic radiographic features of silicosis in 19 horses. J Vet Intern Med. 1991; 5:248-256

- Carlson CS, Weisbrode SE. Bones, joints, tendons, and ligaments. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2012.

- Symons JE, Entwistle RC, Arens AM, et al. Mechanical and morphological properties of trabecular bone samples obtained from third metacarpal bones of cadavers of horses with a bone fragility syndrome and horses unaffected by that syndrome. Aust Vet J. 2012; 73(11):1742-1751.

- Seitz S, Priemel M, Zustin J, et al. Pagets disease of bone: histologic analysis of 754 patients. J Bone Miner Res. 2009; 24:62-69.