Signalment:

20-year-old

female Indian rhesus macaque (

Macaca mulatta).This

animal had 2 months of lethargy, large clitoris, pain/discomfort vaginal

bleeding. The body weight lost 3 kg in 2 months. A large firm mass was palpable

in the lower abdomen, mainly on left side. The mass was round, measuring 7 x7

cm. Ultrasound revealed large mass with multiple round cavities inside. The

animal developed a moderate regenerative anemia. Although extensive care and

treatment were given, euthanasia was elected due to the grave prognosis.

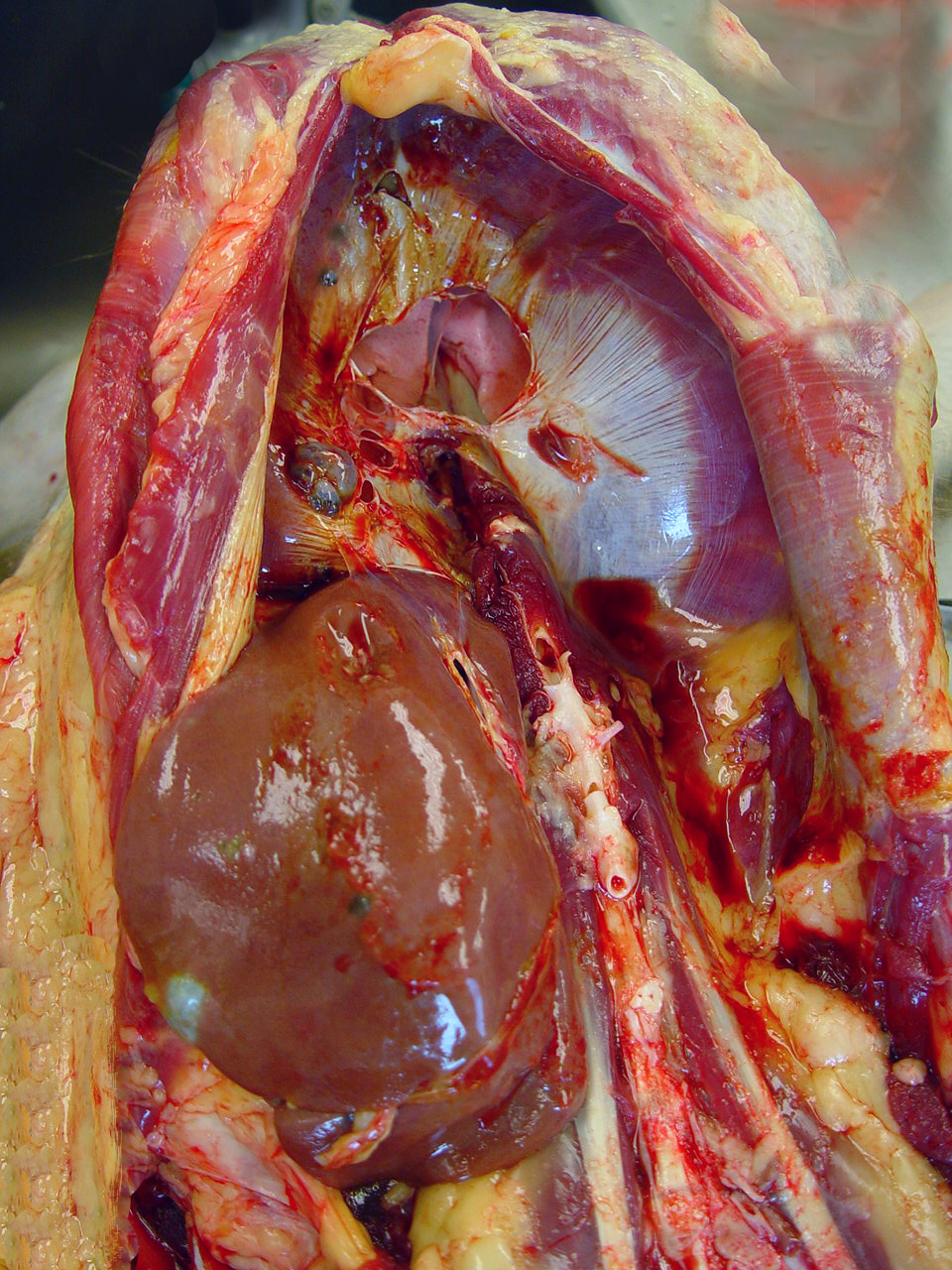

Gross Description:

Presented was a

thin, dehydrated aging animal. A large, firm mass was palpated at the lower

abdomen. The subcutaneous tissue over the abdominal mass was dark-red and

edematous. Extending from the uterus to the abdominal wall and incorporating

with ovaries, ovary ducts, and serosa of the colon was a 15 -20 cm in diameter,

dark-red cystic masses, which contained a large amount of dark-red fluid on the

cut section. Multifocal variable-sized, dark-red cystic masses are also noted

on the diaphragm, liver, and mesentery. The central tendon of the diaphragm was

fragile and easily pierced by force. Other findings included severe thymic

atrophy and mild, bilateral hydronephrosis.

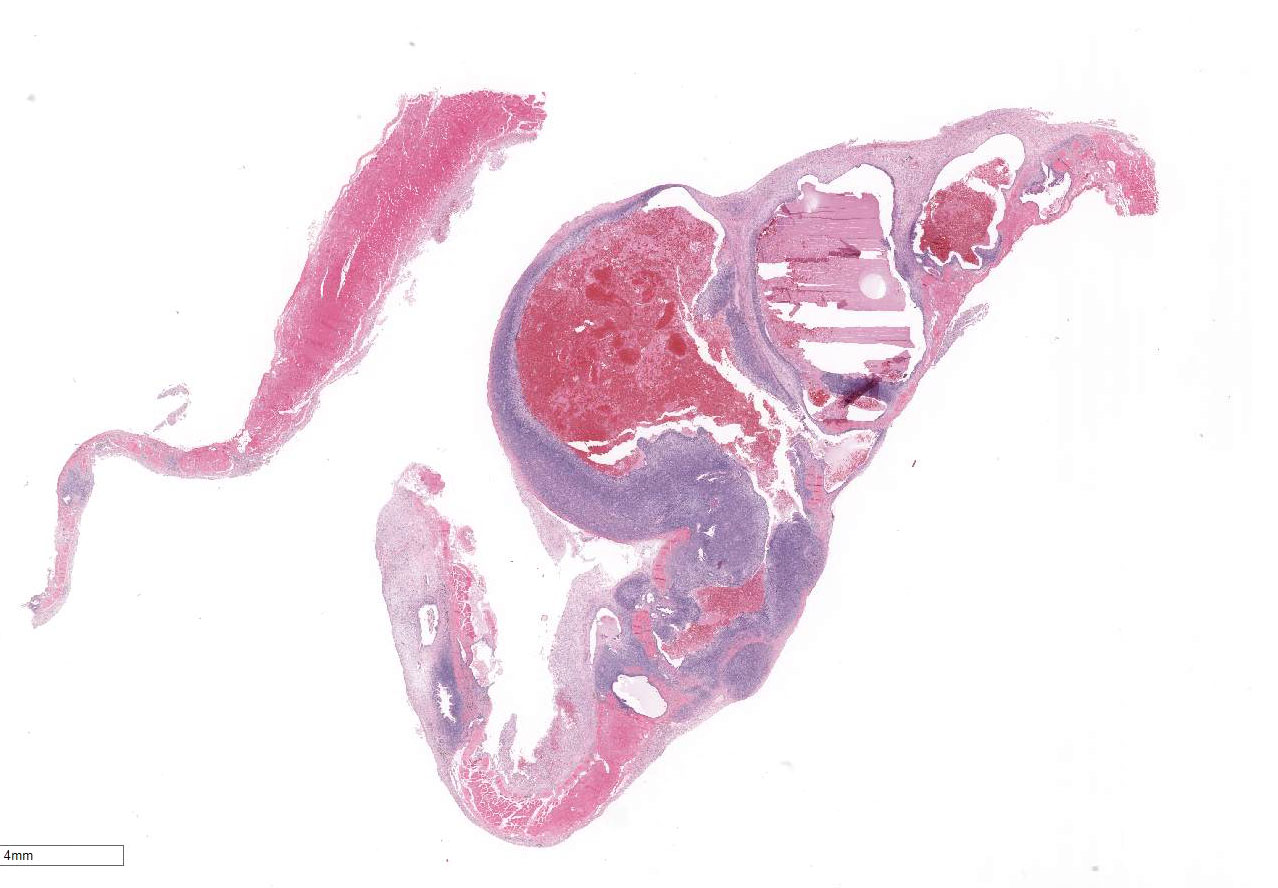

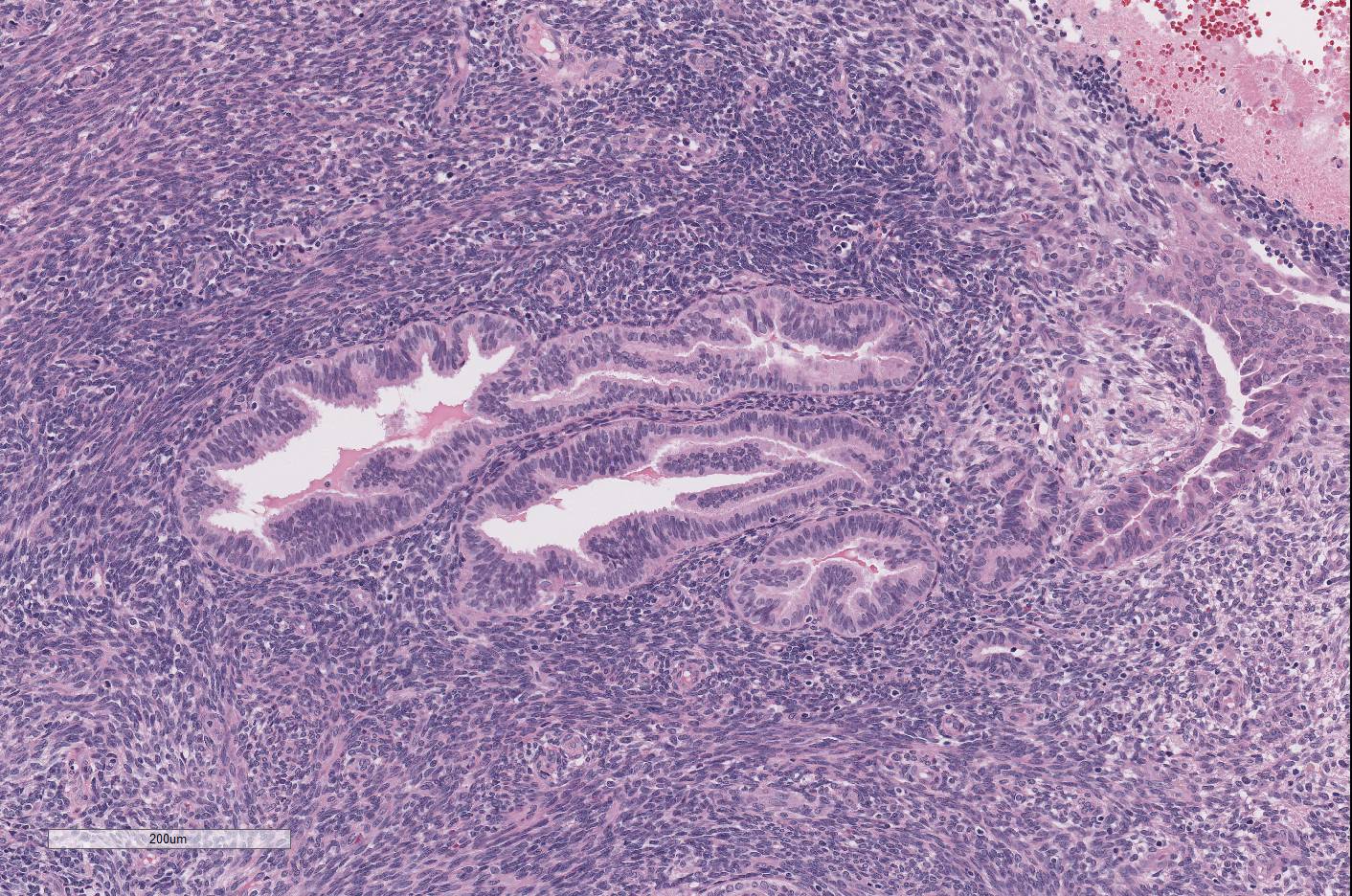

Histopathologic Description:

Expanding

and disrupting the diaphragm are multiple, unencapsulated masses composed of

variable tortuous endometrial glands surrounded by abundant, densely cellular

endometrial stroma. The endometrial glands are generally lined by simple

columnar, ciliated epithelial cells. Some parts of glands are lined by

flattened to pseudostratified cells. Occasionally the epithelial cells form

islands or papillary projections in the lumen. The epithelial cells have

indistinct cell borders, a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, and

prominent basilar nuclei. Nuclei are round to oval with finely stippled

chromatin and 1-2 prominent nucleoli. There are large amounts of amorphous,

eosinophilic material and admixed with numerous erythrocytes. The endometrial

stroma is composed of spindle cells with indistinct cell borders, scant

eosinophilic, fibrillar cytoplasm and an oval to elongate nucleus with finely

stippled chromatin. The mitotic figures

are 1-2/HPF in both glandular epithelium and stroma. Diffusely the

serosa is markedly expanded by reactive fibroblasts, edema, hemorrhage, and

many lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. Some macrophages contain

abundant cytoplasmic brown pigment (hemosiderosis). Multifocally the muscle

adjacent to the masses showed variable degeneration and necrosis.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Diaphragm, Endometriosis.

Lab Results:

N/A

Condition:

Diaphragmatic endometriosis

Contributor Comment:

Endometriosis

usually occurs in the pelvis and the most commonly involved organs are ovaries,

uterosacral and broad ligaments, and parietal pelvic peritoneum. Diaphragmatic

endo-metriosis is rare, often asymptomatic, and always associated with severe

pelvic involvement.

4,7 Ectopic endometriosis has also been reported

in umbilicus, skin, vagina, vulva, cervix, inguinal canal, upper abdominal

peritoneum, liver, spleen, gastrointestinal tract, urinary system, breasts,

pleural cavity, brain, eye, lymph nodes, lung and pericardium in human.

4

Pleural and lung endometriosis have been reported in an aged rhesus macaque1

and sooty mangabey 2009 conference

19, case 01 respectively. Diaphragmatic

endometriosis, like in this case, can involve entire thickness of the muscle.

It is common to extend into pleural space in human, but not presented in this

case.

4 The pathogenesis of endometriosis has

been well discussed in the previous conferences 2011 conference

11, case 01 and 2009 conference

19, case 01. The primary theory of Sampsons three-fold transplantation likely applies to

this case. The retrograde regurgitation of endo-metrial cells passes through

the oviducts into the peritoneal cavity and proliferates in ectopic sites.

8

JPC Diagnosis:

Diaphragm:

Endometriosis, rhesus macaque,

Macaca mulatta.

Conference Comment:

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of well-differentiated, viable,

and hormone responsive endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterus.

1,4,5,7

This is one of the most common gynecologic diseases encountered in female

humans as well as Old World primates.

1 There have been rare reports

of endometriosis in the elephant shrew, long-tongued bat, and one case report

of an endometrioma in a dog.

3,7 The

most widely studied animal model for endometriosis in humans is the baboon. The

prevalence of endometriosis in captive female baboons is as high as 20%. It is

thought that baboons in captivity develop endometriosis at a higher rate than

wild baboons because of regular menstrual cycles without intervening pregnancy

in this population of animals.

7 The vast majority of endometriosis

cases in Old World primates occurs within the abdominal cavity and is grossly

identifiable as blood-filled chocolate cysts which can progress to fibrotic

scars in chronic cases. Typically, endometriosis demonstrates positive

immunoreactivity for pancytokeratin, vimentin, estrogen receptor, and pro-gesterone

receptor.

1

In this case, several conference

participants noted that the endometrial glands are filled with abundant

hemorrhage, consistent with active menses in this animal. The endometrial

tissue in endometriosis is responsive to cycling estrogen and pro-gesterone,

and therefore will undergo cycles of proliferation and degradation in response

to the normal menstrual cycle.

1,7,8 Hemorrhage associated with

endometriosis can be severe enough to cause anemia and can rarely rupture

causing hemorrhagic ascites.

1,2,7,8 Conference participants

discussed various risk factors for the development of endometriosis in

non-human primates. These include chronic un-interrupted estrus cycles

throughout life, resulting in increased endometrial turnover compared to

multiparous primates. Females older than ten years with an affected

first-degree relative are also predisposed. Non-laparoscopic abdominal surgical

procedures, including hysterectomy and cesarean section, are also implicated,

in addition to estradiol implants.

1,5 The moderator also discussed

that aged non-human primates are much more likely to develop endometriosis

compared to older women due to lack of menopause in these species.

5

Unfortunately, the reproductive history of this animal was not provided.

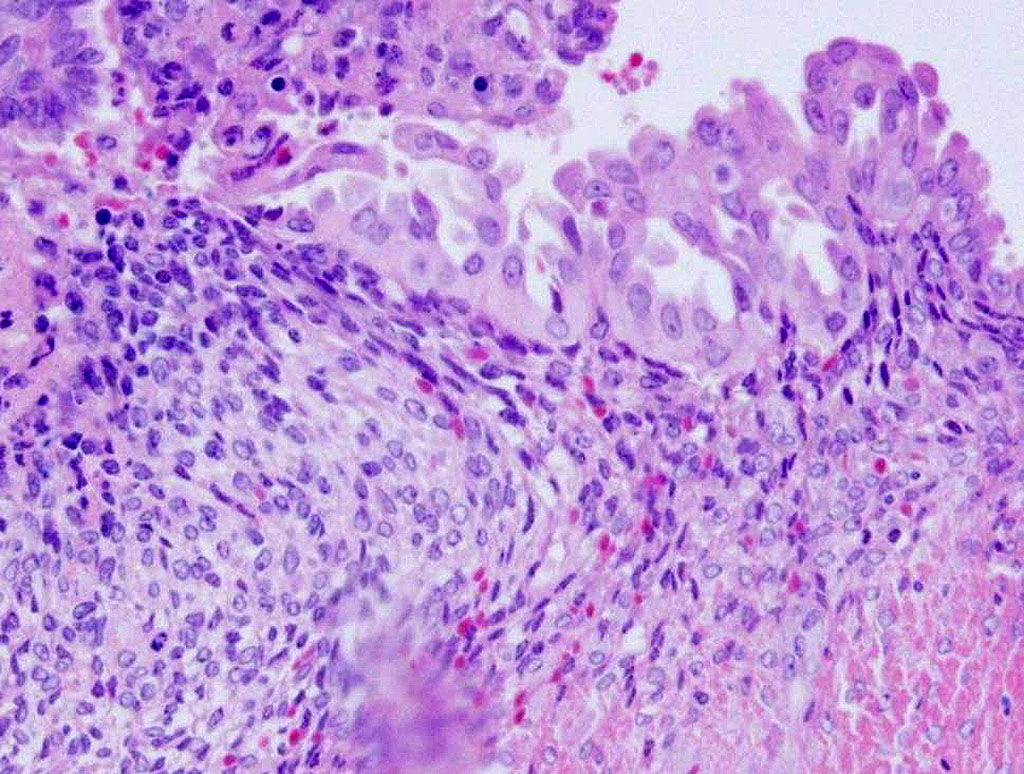

The conference

moderator also discussed the importance of distinguishing well-differentiated

endometrial tissue in endometriosis from endometrioid carcinoma. In

endometrioid carcinoma, glands will be irregular with little to no intervening

stroma and demonstrate significant nuclear atypia. Endometrioid carcinoma has

been rarely reported to develop from endometriosis.

1,4 In addition,

multifocally

within this section there are large areas where the endometrial epithelial cell

nuclei are rounded and vesicular with abundant pale vacuolated cytoplasm,

consistent with stromal decidualization and epithelial plaque reaction.

Decidualization of the endometrial glands occurs under the influence of

progesterone and is a response to blastocyst implantation or other trauma to

the endometrial stroma. This is required for maintenance of normal pregnancy in

humans and non-human primates.

2 In endometriosis, it is thought that

this reaction develops secondary to elevated pro-gesterone. Endometrial

decidualization is non-neoplastic, but grossly and histo-logically mimics

malignant neoplastic lesions such as mesothelioma and carcino-matosis. In a

recent article in

Veterinary Pathology, Atkins et al. demonstrates that

the decidualized stroma stained positive for vimentin, CD10, progesterone, and

estrogen consistent with reported deciduosis in humans.

2

References:

1. Assaf BT, Miller

AD. Pleural endometriosis in an aged rhesus macaque (

Macaca mulatta): A

histopathologic and immunohistochemical study.

Vet Pathol. 2012;

49(4):636-641.

2. Atkins HM,

Lombardini ED, Caudell DL, et al. Decidualization of endometriosis in

macaques.

Vet Pathol. 2016; 53:1252-1258.

3. Paiva BH, Silva

JF, Ocarino NM, et al. A rare case of endometrioma in a bitch.

Acta Vet

Scand. 2015; 57:31.

4. Ceccaroni M,

Roviglione G, Rosenberg P, Pesci A, Clarizia R, Bruni F, et al. Pericardial,

pleural and diaphragmatic endometriosis in association with pelvic peritoneal

and bowel endometriosis: A case report and review of the literature.

Wideochir

Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2012; 7(2):122-131.

5. Fazleabas

AT, Brudney A, Gurates B, Chai D, Bulun S. A modified baboon model for

endo-metriosis.

Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002; 955:308-17.

6. Hastings

JM, Fazleabas AT. A baboon model for endometriosis: Implications for fertility.

Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2006; 4:1-7.

7. Nezhat

C, King LP, Paka C, Odegaard J, Beygui R. Bilateral thoracic endometriosis

affecting the lung and diaphragm.

JSLS. 2012; 16(1):140-142.

8. Van der Linden

PJ. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis.

Hum Reprod. 1996;

11(3):53-65.