Signalment:

14-year-old, thoroughbred, gelding,

horse, (

Equus caballus).The patient was admitted for evaluation of chronic colic, and had

a distended abdomen on arrival. The horse was diagnosed with uroperitoneum and

was euthanized after a tear in the ventral portion of the urinary bladder was

confirmed on abdominal ultrasound and cystoscopy. Clinical signs of disease

involving other organ systems (

e.g. respiratory tract) were not

reported.

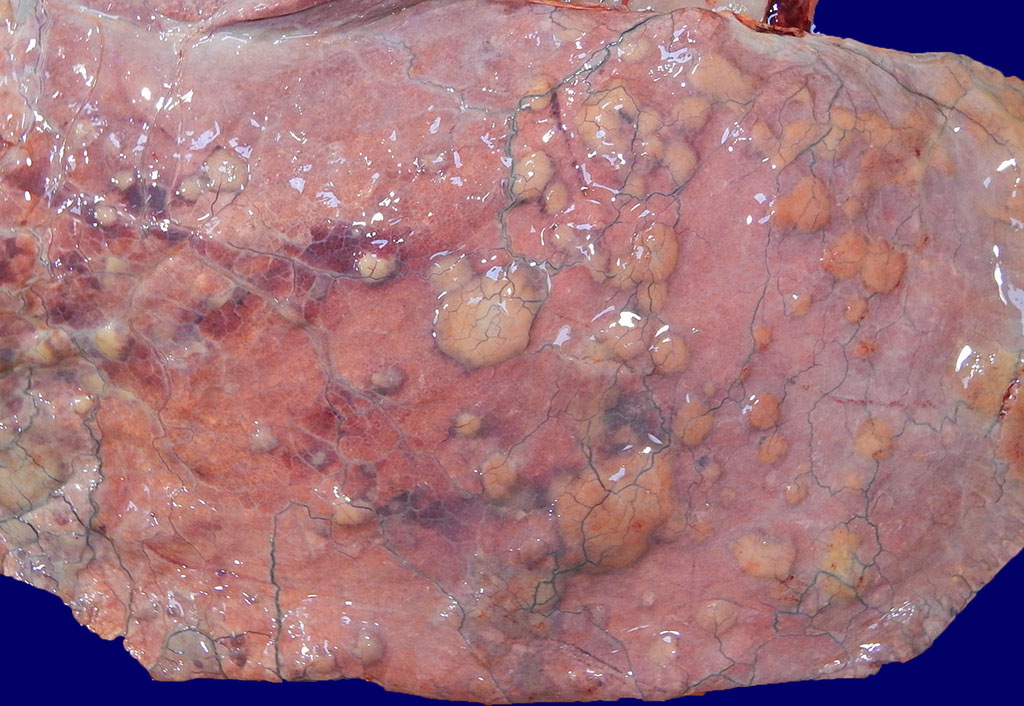

Gross Description:

The patient was in satisfactory nutritional and good postmortem

condition. The peritoneum contained abundant turbid, light-yellow fluid with a

distinct ammonia odor

(i.e. urine), and was hyperemic with adherent

plaques of fibrin. The urinary bladder was distended and a 7 x 5 cm thin,

gray-green and friable (necrotic) focus within the ventral wall was confirmed.

However, examination of the lungs revealed multifocal to coalescing 0.5- 5 cm

diameter firm tan nodules that extended into all fields, replacing the

pulmonary parenchyma and elevating the visceral pleura (figure 1). Intervening

pulmonary parenchyma was pale pink to dark red and mildly firm cranioventrally.

The brain, spinal cord, and remainder of the thoracic and abdominal viscera

were grossly unremarkable.

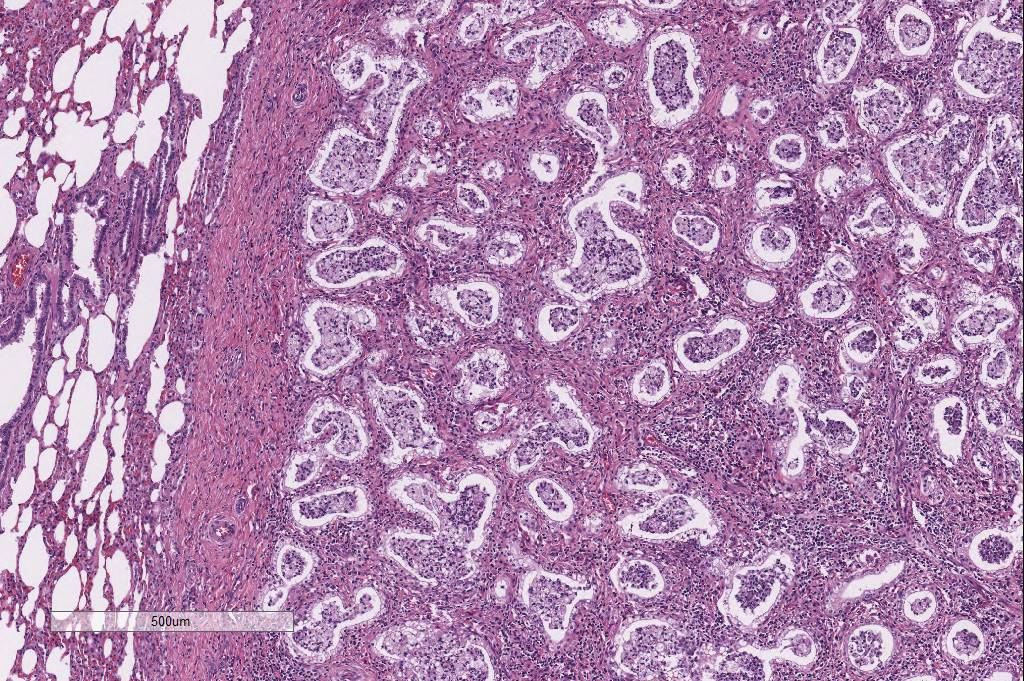

Histopathologic Description:

Approximately 80% of the pulmonary parenchyma was effaced by

multifocal to coalescing nodules composed of proliferating spindle cells

(fibroblasts) embedded within a fibrillar eosinophilic (collagenous) stroma,

and infiltrated by large numbers of lymphocytes and histiocytes, with fewer

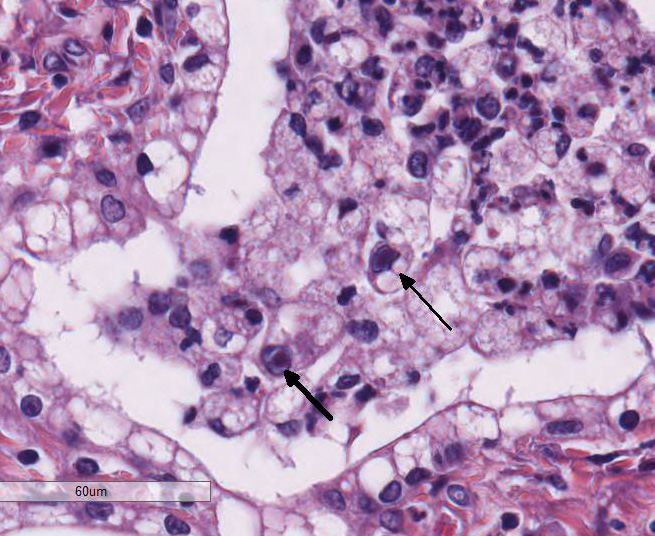

neutrophils. Occasionally, alveolar macrophages contained 3-4μm diameter

eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies that peripheralized the chromatin

(Cowdry Type A inclusions; figure 2 (arrow)). Within affected regions, the

majority of alveoli were lined by plump cuboidal epithelial cells

(bronchiolization). Affected alveoli, and occasional bronchi and bronchioles,

were filled with numerous foamy macrophages, neutrophils, and cell debris.

Within unaffected regions of lung, alveoli were often ectatic (hyperinflated),

and there was mild multifocal alveolar hemorrhage.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: severe chronic

multifocalcoalescing sclerosing lymphohistiocytic and neutro-philic

bronchointerstitial pneumonia with intrahistiocytic intranuclear inclusion

bodies (consistent with equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis).

Lab Results:

None.

Condition:

Equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis, EHV-5

Contributor Comment:

Equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis (EMPF), one of the

relatively few differentials for interstitial lung disease in the horse,

results in a unique gross and histologic appearance dominated by a nodular

pattern of marked interstitial fibrosis.

10 Clinical signs of

affected horses may include tachypnea, dyspnea, nasal discharge, coughing,

lethargy, inappetence, and poor body condition. Affected horses may have

increased bronchovesicular sounds, fever, and/or hypoxemia on clinical exam.

14

Hematology typically reveals a neutrophilia (in some cases with increased

bands), lymphopenia or lymphocytosis, and monocytosis.

7,14 A nodular

interstitial pattern is often identified on thoracic radiographs and

ultrasound, resulting in differential diagnoses of EMPF, fungal pneumonia and

pulmonary neoplasia. Concurrent with the interstitial pulmonary disease,

thoracic ultrasonography may also reveal pulmonary artery dilation, consistent

with pulmonary hypertension. Transtracheal wash fluid is predominantly

neutrophilic (degenerate or non-degenerate), with fewer macrophages.

14

No breed or sex predilection has been established, and although affected horses

are typically middle-aged or geriatric, cases have been reported in horses as

young as four years-old.

12

Two gross patterns of EMPF have been described, both of which are

characterized by multifocal moderately firm, tan, bulging nodules throughout

the pulmonary parenchyma. In the more common of the two gross forms (the form

exhibited by this horse), these nodules are numerous but small (up to 5 cm in

diameter), and coalesce, often resulting in scant intervening parenchyma. In

the second gross pattern, the nodules are less frequent, larger (up to 10 cm in

diameter), and discrete, with the intervening pulmonary parenchyma largely

unaffected.

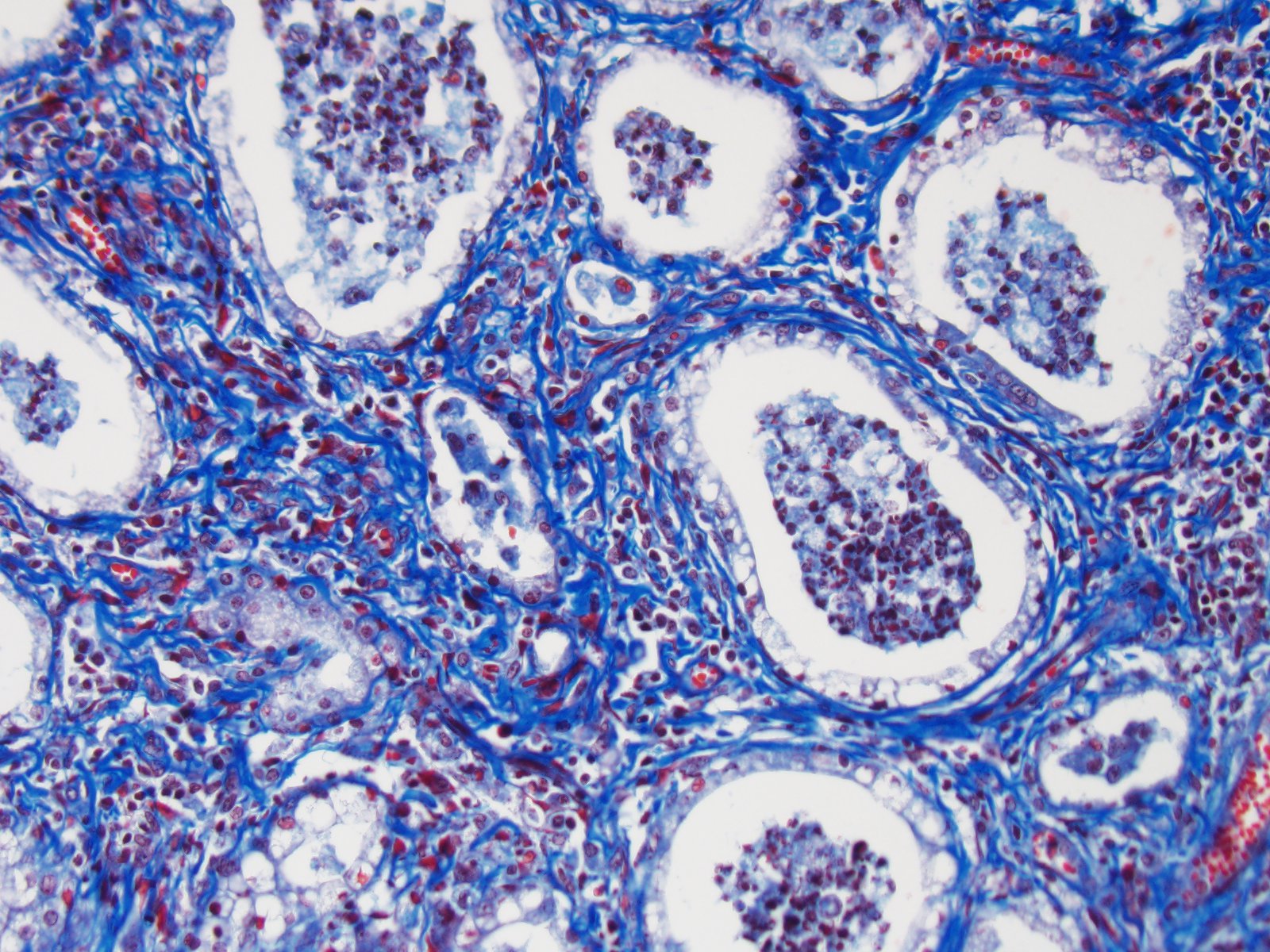

12 Histologically, both gross forms are characterized by

extensive interstitial deposition of mature collagen, accompanied by moderate

mixed inflammatory infiltrates, consisting pre-dominantly of lymphocytes,

macrophages and neutrophils. Alveoli in affected regions are typically lined by

plump, cuboidal epithelium, and airways contain abundant neutrophils and

macrophages. Alveolar macrophages occasionally contain ampho-philic to

eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies. Less frequently, the nodules

consist of dense sheets of disorganized collagen that completely efface the

normal alveolar pattern.

12

Equine

herpesvirus-5 (EHV-5) is a gamma herpesvirus strongly associated with EMPF, and

can be identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunohistochemistry

(IHC), in situ hybridization, virus isolation, and transmission electron

microscopy (TEM).

2,7,12-14 Although causality has not been proven by

meeting all of Kochs postulates, the main histologic and immunohistochemical

features have been recapitulated in horses inoculated with EHV-5 isolated from

EMPF-affected horses.

13 However, because inoculated horses lacked

clinical signs associated with EMPF, were PCR-negative for the inoculated EHV-5

viruses (within the lungs), and the virus was unable to be re-isolated, the

authors suggest that the immuno-histochemical

detection of virus in the inoculated horses having deposition of fibrous

connective tissue likely represented a pre-clinical, yet latent, phase of viral

infection.

13 Further supporting EHV-5 as an important etiologic

factor in the development of EMPF, quantitative real-time PCR performed in an

affected horse revealed higher viral load within the lungs than in other

tissues, with the highest load within the most severely affected/fibrotic

regions of lung.

4 In addition, gamma herpesviruses have been

associated with fibrotic lung diseases in other species, including a variably

fibrotic broncho-interstitial pneumonia with syncytial cell formation in

donkeys associated with asinine herpesvirus-4 and 5 (AHV-4 and 5),

3

and human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis associated with human herpesvirus-8

(HHV-8) and Epstein-Barr virus.

10,11 Moreover, mice that are

knockouts for the IFNγ cytokine receptor (an important mediator of the Th1

antiviral response), develop progressive pulmonary interstitial fibrosis after

chronic infection with murine gamma herpesvirus-68.

5,11 Although the

precise mechanisms of gamma herpesvirus-induced fibrosis and immune system

evasion in most species are unknown, they are likely related to the specific

viral-induced cytokine, chemokine, and/or receptor profile within the host, which either directs the immune system toward a Th2

response (thereby inhibiting a Th1 response and facilitating fibrosis), or at

least prevents an effective Th1 antiviral response.

6,11 Such

mechanisms have already been established in the study of human gamma

herpesviruses, including viral CCL-1 (vCCL-1), vCCL-2, and vCCL-3 encoded by

HHV-8 that activate Th2 cell chemokine receptors (CCR8, CCR3 and CCR8, and

CCR4, respectively), and a viral IL-10 homologue produced by human Epstein-Barr

virus that results in inhibition of the Th1 antiviral response.

6,11

In spite of supporting evidence of EHV-5 infection inciting EMPF, EHV-5 may not

be the sole cause. As with many infectious diseases, concurrent viral

infections (such as EHV-2 and AHV-4 or 5), and the hosts immune status, may

also be important contributors to the pathogenesis of EMPF.

1,5,11,12

Although

successful treatment with corticosteroid and antiviral (acyclovir) therapy is

reported, overall, response to treatment is variable and the prognosis of this disease is generally considered poor.

14 This case

was unusual in that there were no reported clinical signs that were clearly

attributable to respiratory disease. However, a preclinical, latent phase of

infection is considered unlikely given the presence of numerous inclusion

bodies. Although the uroperitoneum accounted for the most recent episode of

colic, it is possible that the pneumonia caused chronic lethargy and

inappetence, vague signs that were interpreted as chronic colic. Regional trans-mural

necrosis of the urinary bladder was confirmed histologically, and was

attributed to pressure-induced ischemia secondary to distension. As there was

no evidence of urethral obstruction, a neurogenic cause was suspected. However,

no histologic lesions were identified within the spinal cord.

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Fibrosis, interstitial, nodular, multifocal to coalescing,

severe with lymphohistiocytic interstitial inflammation, alveolar neutrophilic

and histiocytic exudate, type II pneumocyte hyperplasia and histiocytic intranuclear

viral inclusion bodies, thoroughbred,

Equus caballus.

Conference Comment:

We

thank the contributor for both an excellent example and thorough summary of

equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis (EMPF) in horses. This entity has also

been extensively reviewed in previous Wednesday Slide Conferences (

2011 Conference

1 Case 2

2012 Conference

24 Case 3

2013 Conference

18 Case 1

, but it was chosen again because of its highly distinctive and

unique histomorphology. Participants identified multifocal discrete lung

nodules with abundant interstitial fibrosis, marked type II pneumocyte

hyperplasia, and irregular alveolus-like spaces filled with an inflammatory

exudate composed of neutro-phils, fibrin, and alveolar macro-phages which

occasionally contain a 2-4 um magenta intranuclear inclusion body. Conference participants also noted especially prominent pleural

arteries in areas adjacent to the nodules of fibrosis with hypertrophic smooth

muscle in the tunica media indicative of pulmonary hypertension associated with

pulmonary fibrosis.

As mentioned by the

contributor, gamma herpesviruses have been associated with progressive

pulmonary fibrotic disorders in humans, donkeys, horses, and rodents. In dogs,

canine idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a progressive pulmonary fibrotic

disorder predominantly in aged West Highland white terriers (WHWT).

9

Recently, investigators have tried to elucidate a relation between this

disorder in WHWTs and gamma-herpesvirus infection; however, no evidence a

connection was found. Given this conditions predilection for WHWT, it is

thought that there is a genetic component to this disease in this breed of dog

rather than an infectious etiology.

9

In addition to pulmonary

fibrosis, conference participants discussed the association of a gamma

herpesvirus with retroperitoneal fibromatosis (RF), an aggressive proliferation

of highly vascular fibrous tissue subjacent to the peritoneum involving the

ileocecal junction and mesenteric lymph nodes in rhesus macaques.

10

RF is associated with co-infection of simian retrovirus 2 (SIV) causing simian

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (SAIDS) and RF-associated herpesvirus

(RFHV). This condition is closely related to Kaposis sarcoma in humans, caused

by co-infection of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) and human immuno-deficiency virus

(HIV), and is one of the first illnesses associated with the development of

AIDS.

10 Additionally, rhesus macaque rhadinovirus, another

gammaherpesvirus, is also closely related to HHV8 and both have been associated

with the development of B-cell lymphoma.

8

References:

1. Back H, Kendall A, Grandón R, et al. Equine multinodular pulmonary

fibrosis in association with asinine herpesvirus type 5 and equine herpesvirus

type 5: a case report.

Acta Vet Scand. 2012;54(57):1-5.

2. Caswell JL, Williams KJ: Equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis.

In: Maxie MG ed.

Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers pathology of domestic animals. Vol

2. 6

th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2016:568-569.

3. Kleiboeker SB, Schommer SK, Johnson PJ, et al. Association of two

newly recognized herpesviruses with interstitial pneumonia in donkeys (

Equus

asinus).

J Vet Diagn Invest. 2002;14:273-280.

4. Marenzoni ML, Passamonti F, Lepri E, et al. Quantification of

Equid

herpesvirus 5 DNA in clinical and necropsy specimens collected from a horse

with equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis.

J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011;23(4):802-806.

5. Mora AL, Woods CR, Garcia A, et al. Lung infection with

γ-herpesvirus induces progressive pulmonary fibrosis in Th2-biased mice.

Am

J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L711-L721.

6. Nicholas J. Human gamma-herpesvirus cytokines and chemokine

receptors.

J Interf Cytok Res. 2005;25:373-383.

7. Niedermaier G, Poth T, Gehlen H. Clinical aspects of multinodular

pulmonary fibrosis in two warmblood horses.

Vet Rec. 2010;166:426-430.

8. Orzechowska BU, Powers MF, et al. Rhesus macaque

rhadinovirus-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Animal model for KSHV associated

malignancies.

Blood. 2008; 112:4227-4234.

9. Roels E, Dourcy M, et al. No evidence of herpesvirus infection in

West Highland white terriers with canine idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Vet

Pathol. 2016; 53(6):1210-1212.

10. Rose

TM, Strand KB, et al. Identification of two homologs of the Kaposis

sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in retroperitoneal

fibromatosis in different macaque species.

J Virol. 1997; 71:4138-4144.

11. Tang

Y, Johnson JE, Browning PJ, et al. Herpesvirus DNA is consistently detected in

lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

J Clin Microbiol.

2003;41(6):2633-2640.

12. Williams

KJ. Gammaherpesviruses and pulmonary fibrosis: evidence from humans, horses and

rodents.

Vet Pathol. 2014;51(2):372-384.

13. Williams

KJ, Maes R, Del Piero F, et al. Equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis: a newly

recognized herpesvirus-associated fibrotic lung disease.

Vet Pathol. 2007;44:849-862.

14. Williams

KJ, Robinson NE, Lim A, et al. Experimental induction of pulmonary fibrosis in

horses with gammaherpesvirus Equine Herpesvirus 5.

PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77754,

doi. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077754.

15. Wong

DM, Belgrave RL, Williams KJ, et al. Multinodular pulmonary fibrosis in five

horses.

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;232(6):898-905.