Signalment:

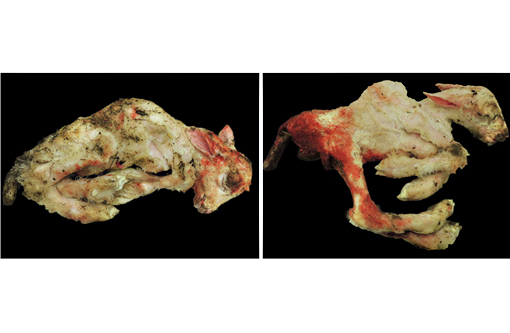

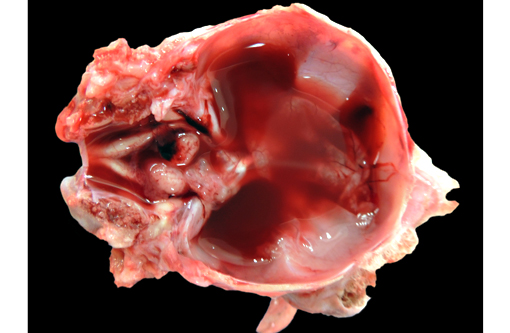

Gross Description:

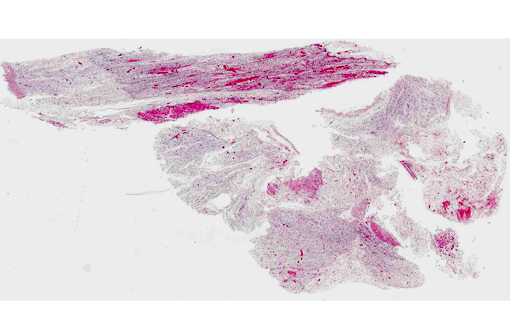

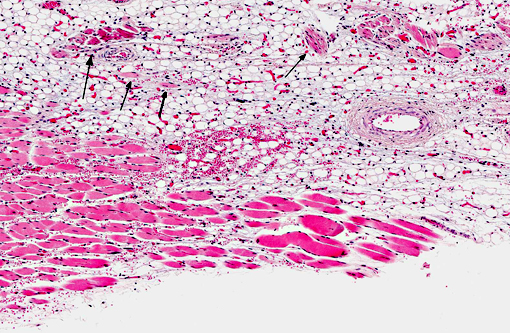

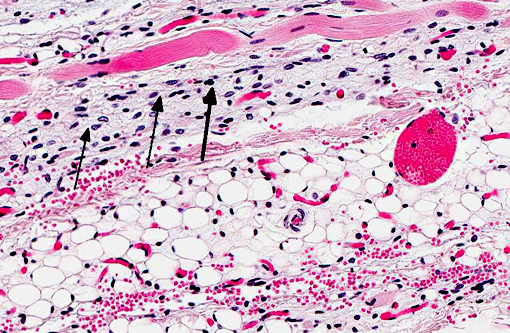

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The clinical signs of CVV infection in adults are generally subclinical causing only a transient febrile response. In sheep, CVV is a well-recognized cause of congenital malformations and early fetal loss. Infection of ewes between 27 to 50 days of gestation results in congenital abnormalities including arthrogryposis, torticollis, hydranencephaly, hydrocephalus, porencephaly, microencephaly, cerebral and cerebellar hypoplasia, micromelia, anasarca and oligohydroamnios; mummification, reabsorption and dead embryos without deformities are also seen.(4) Infection at 2836 days gives rise to central nervous system and musculoskeletal defects while infection at 3742 days gives rise to musculoskeletal deformities only. Histological changes in addition to the muscular changes presented in this case include areas of necrosis and loss of paraventricular neuropil in the brain together with a reduction in the number of motor neurons.

CVV can be diagnosed on the basis of suggestive fetal malformations, histopathological changes, the demonstration maternal and neonatal antibodies and the presence of virus in pools of resident mosquitoes and viremic adults. At birth, CVV generally cannot be isolated aborted fetuses. Experimentally in sheep, CVV could be isolated from the allantoic fluid at less than 70 days of gestation but was not recovered from the allantoic fluid of fetuses after 76 days gestation.(4) Virus neutralization and ELISA testing are available for serological testing while PCR and virus isolation are available for virus detection.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Plant toxins and teratogenic viruses, including those belonging to the genera Orthobunyavirus, Pestivirus and Orbivirus, are often associated with congenital fetal malformations of the musculoskeletal and central nervous systems in ruminants. The most common cause of arthrogryposis, whether due to teratogenic plants or viruses, is denervation.(7) Ingestion of wild lupins (Lupinus caudatus, sericeus, or formosus) by pregnant cows may result in crooked calf disease, which is characterized by fetal musculoskeletal malformations such as arthrogryposis, torticollis, scoliosis, kyphosis, brachygnathia superior or palatoschisis. Similarly, maternal ingestion of Veratrum californicum can cause arthrogryposis or cyclopia in neonatal ruminants, and Nicotiana spp. (tobacco), jimsonweed and wild black cherry have also been associated with arthrogryposis; however, these plant toxins are not generally linked with hydranencephaly or cerebellar hypoplasia.(7)

Cache Valley, Akbane, Schmallenberg and Aino viruses belong to the genus Orthobunyavirus and are known for causing outbreaks of arthrogryposis, hydranencephaly and occasionally cerebellar hypoplasia in calves and lambs (see WSC 2012-2013, conference 22, case 3, table 1). Cache Valley virus is more common in sheep, while Akbane and Aino viruses primarily affect cattle. Fetal infection of calves and lambs with bovine virus diarrhea virus or border disease virus (pestiviruses) often results in cerebellar hypoplasia, or, less commonly, hydranencephaly, porencephaly, hydrocephalus or ocular abnormalities. Likewise, classical swine fever virus (also a pestivirus) infection can cause mummification, arthrogryposis and cerebellar hypoplasia in piglets. Infection with bluetongue virus (orbivirus) causes hydranencephaly and porencephaly in lambs and occasionally calves; however, arthrogryposis is not a characteristic lesion. Wesselsbron virus (flavivirus) is associated with mummification, hydranencephaly, arthrogryposis, porencephaly and cerebellar hypoplasia in lambs and calves.(3,7)

Virus-induced teratogenic effects are far less common in small domestic animals and laboratory species than in livestock. One exception is feline parvovirus which causes cerebellar hypoplasia in kittens due to selective necrosis of the external granular cell layer. Less commonly, canine parvovirus and Kilham rat virus (also a parvovirus) can also result in cerebellar hypoplasia in neonatal dogs and rats, respectively.(3,5)

References:

2. Blackmore CGM, Grimstad PR. Cache Valley and Potosi viruses (Bunyaviridae) in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus): experimental infections and antibody prevalence in natural populations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59(5):704-709.

3. Maxie MG, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 1. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Limited; 2007:304-322.

4. OIE. 2008. Chapter 2.9.1 - Bunyaviral diseases of animals (excluding Rift Valley fever). Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals 2012. Accessed: 25/02/2013. URL: http://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/2.09.01_BUNYAVIRAL_DISEASES.pdf

5. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007;127-129.

6. Sahu, SP, Pedersen, DD, Ridpath, HD, Ostlund, EN, Schmitt, BJ, Alstad, DA. Serological survey of cattle in the northeastern and north central United States, Virginia, Alaska, and Hawaii for antibodies to Cache Valley and antigenically related viruses (Bunyamwera serogroup viruses). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67(1):119-122.

7. Thompson KG. Bones and joints. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Limited; 2007:60-62, 204-206.