CASE I:R46-18-5 (JPC 4134356)

Signalment:

Adult domestic shorthair cat (Felis catus)

History:

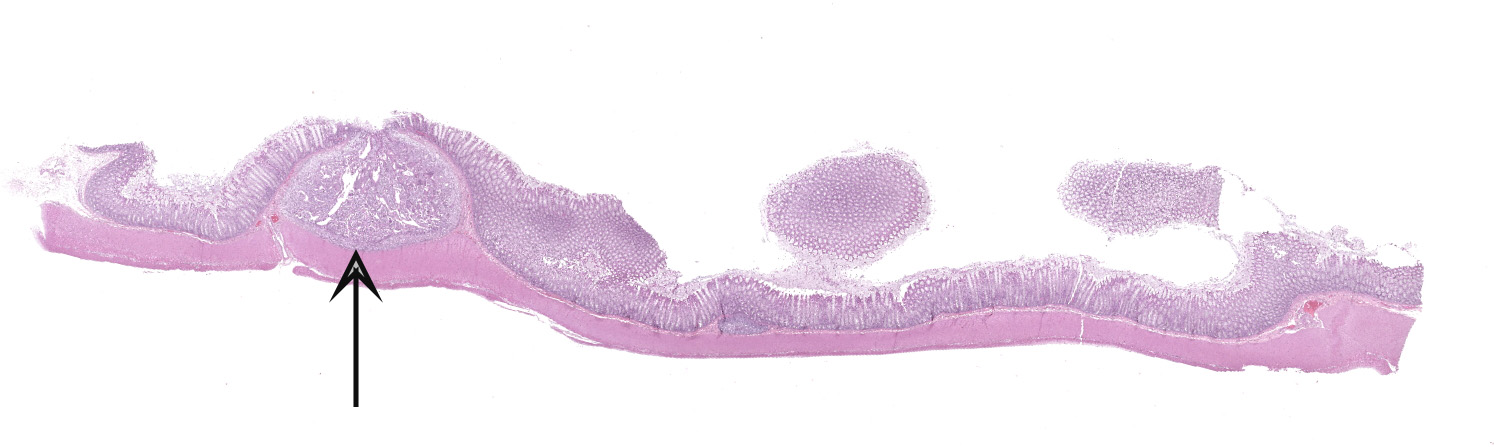

A feral cat, trapped for spay, neuter and release was euthanized due to FIV positive status. The cat was submitted to the parasitology department of Ross University School of Veterinary medicine for nematode collection. Colonic nodules, seen during nematode collection, were excised and submitted to the pathology department for histological evaluation.

Gross Pathology:

There were multiple large (4-8mm in diameter), slightly raised, pale tan nodules in the colonic wall. The nodules appeared to be located in the submucosa, and were visible from both the serosal and mucosal surface. Small pits or depressions were seen on the mucosal surface of the nodules.

Laboratory results:

No laboratory findings reported.

Microscopic Description:

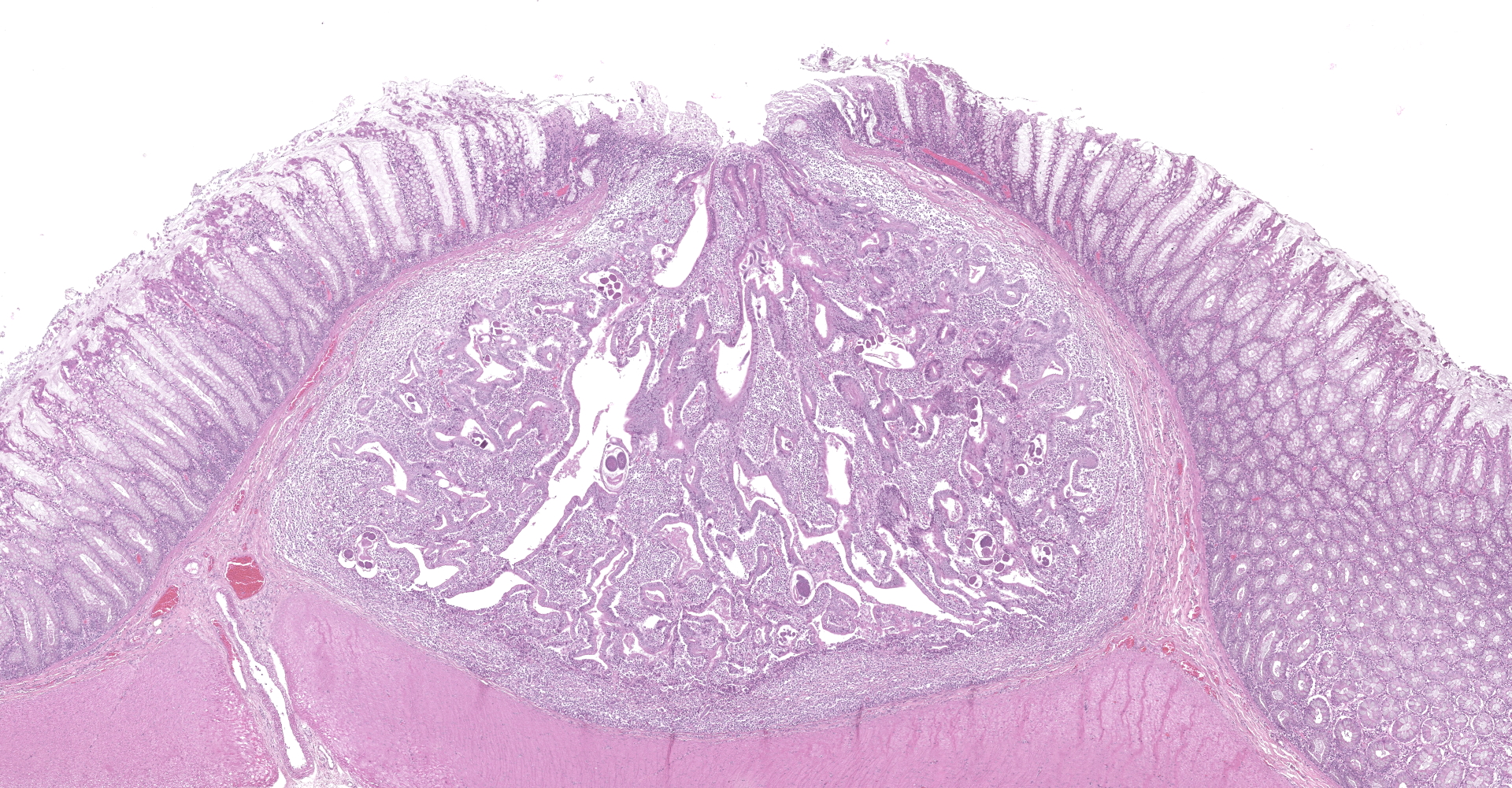

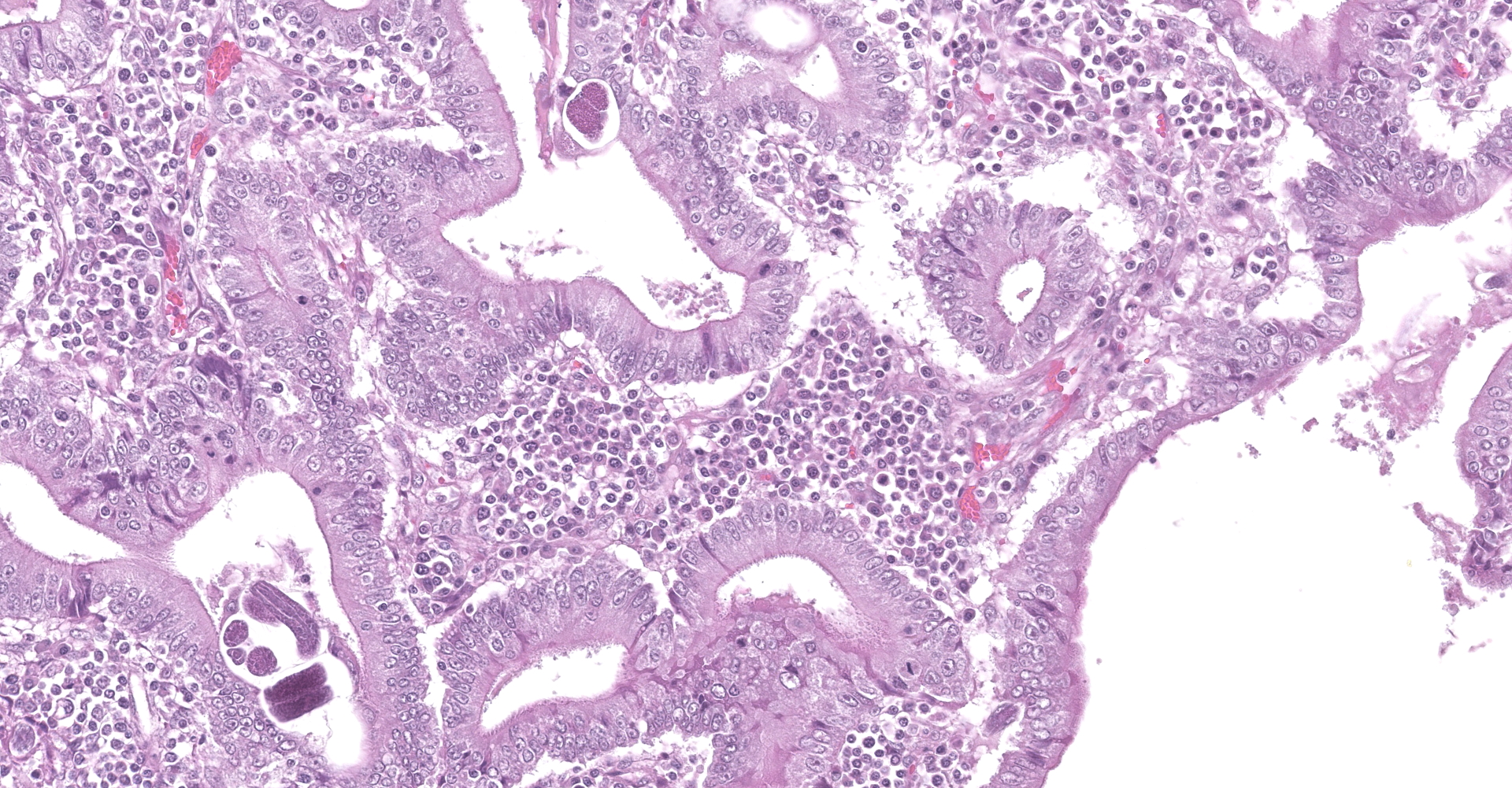

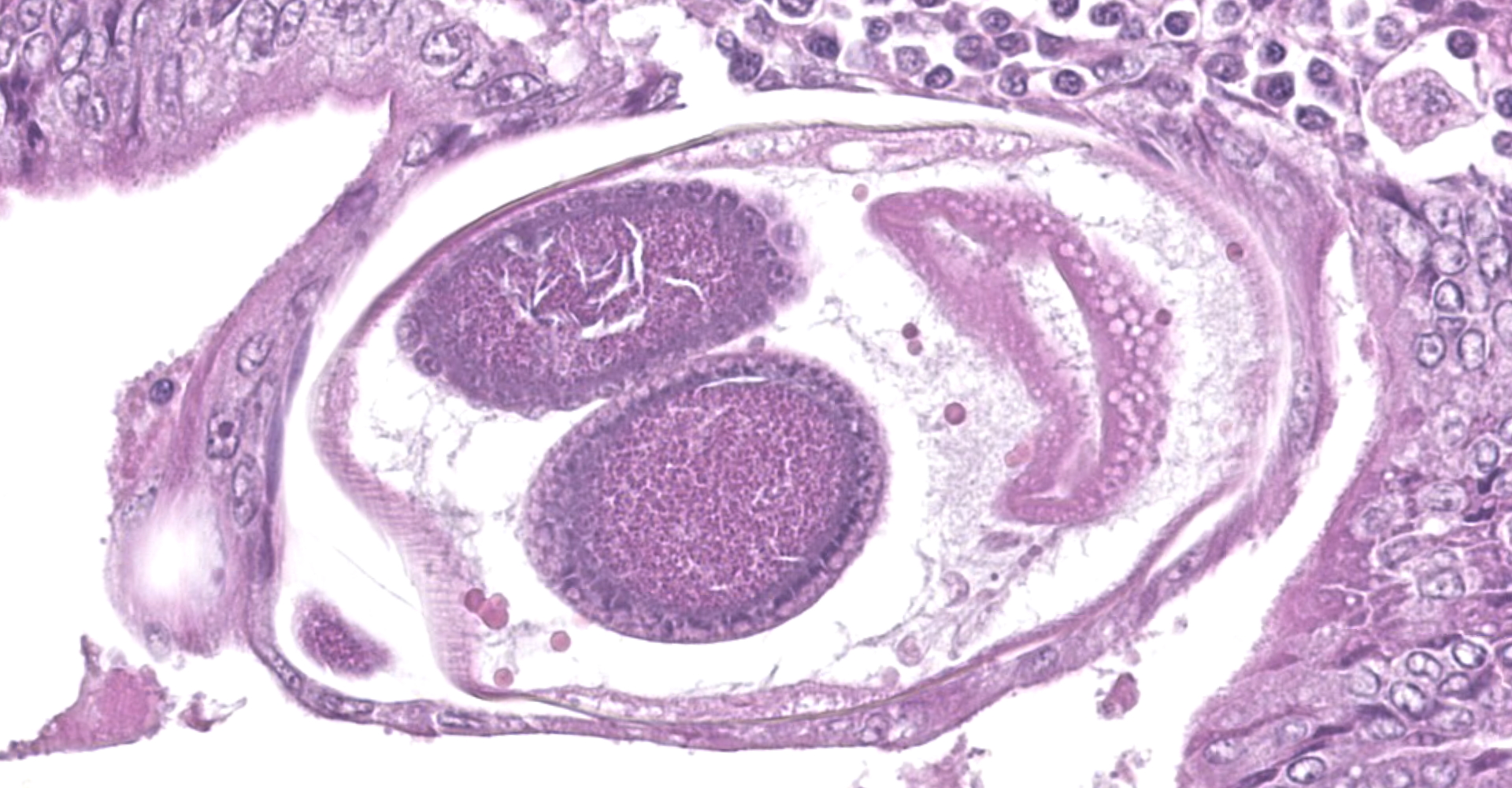

Colon. Expanding the submucosa, and elevating the mucosa, are several 4-8mm in diameter, discrete nodules composed of tubules of herniated hyperplastic mucosal epithelial cells. The latter form branching tubules, surrounded and separated by lymphocytes, plasma cells and occasional macrophages admixed with adult nematodes, eggs, and larvae. Occasionally tubules contain protein or necrotic cell debris. Adult nematodes and eggs are also within tubules. Occasionally larvae are within the tubules and interstitium of the overlying mucosa. Adult females are approximately 110µm in diameter and have platymyarian musculature, paired genital tracts, and intestine composed of uninucleate cells. Larvae are approximately 15-20µm in diameter. A rhabditiform esophagus is rarely identified within larvae. Eggs are ovoid, 30x50µm in diameter and contain morulae or larvae. The overlying mucosa is attenuated and mildly eroded.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Multifocal colonic epithelial nodular hyperplasia and lymphoplasmacytic colitis with intralesional Strongyloides sp. adults, eggs and larvae.

Contributor's Comment:

Strongyloides is a genus of nematode with a complex life cycle involving free living adult stages in the environment and intestinal parasitism of a wide variety of host species. The most important veterinary species are S. papillosus in ruminants, S. westerii in horses, S. ransoomi in swine and S. stercoralis in dogs, cats, humans and non-human primates, and S. felis, S. planiceps and S. tumefaciens in cats.5

Hosts become in-fected by percu-taneous pene-tration, or inge-stion, by third stage filariform larvae (L3), which migrate to the intestine, typ-ically through the lungs.5 L3 devel-op into adult, parthenogenetic females, typically localized within small intestinal mucosa, and reproduce asexually releasing eggs or first stage rhabditiform larvae (L1) in the feces. Environmental L1 can develop directly into infectious L3 larvae, or into free-living adult males or females which produce eggs and larvae by sexual reproduction. Likewise, their progeny may either develop into new generations of infectious L3 larvae or noninfectious free-living adults. Further-more, at least in S. stercoralis, L1 can develop to L3 within the intestine, and migrate through the intestinal wall, back to the small intestine to complete a new parasitic cycle within the same host (autoinfection).5 Most infections are prob-ably asymptomatic, but diarrhea and rarely death, can be associated with Strongyloides infection in young animals.5

Strongyloides sp. within colonic nodular epithelial hyperplasia was first described in two US cats, by Price and Dikmans 1927,4 and later in a few case reports from the United States1,2 and Brazil.3 The pathology in all cases, has been similar, with female adult Strongyloides only observed within nodules in the colonic submucosa, and nodules histologically consisting of epithelial cells forming tubules, extending into the submucosa, supported by stroma infiltrated by lymphoid cells, and with sections of parasitic female nematodes and larvae throughout the tubules and stroma.

The location within colonic nodules, and associated pathology (nodular epithelial hyperplasia) is atypical for Strongyloides spp. in general. For all other species described, nematode stages are confined to the proximal small intestinal mucosa, and associated pathology includes villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and eosinophilic to lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the lamina propria.6

The Strongyloides sp. observed within feline colonic nodules was designated as a separate species, Strongyloides tumefaciens, by the authors who first described it in 1927.4 The species designation was based primarily on the unusual location and lesion, rather than on nematode morphology. Thus, the validity of this species is questionable, and a molecular genetic approach to this parasite's identification would seem warranted.

Contributing Institution:

JPC Diagnosis: Colon: Crypt hyperplasia, focal, severe with crypt herniation

and numerous rhabditoid adults, larvae and eggs.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a good review of the complex and unique lifecycle of the genus Strongyloides as well as the various species infected. This genus is of significant histori-cal significance, particularly in livestock. However, it has been significantly suppressed in recent decades, likely due to extensive use of macrocyclic lactone anthelmintics and/or improved hygiene.5

Also known as threadworms, Strongyloides spp. are grouped within the Rhabditoidea superfamily and are small (3-8mm), slender nematodes discovered over 140 years ago in French troops returning from present day Vietnam.5,7 Its name is derived from the Greek words 'strongylos' meaning 'round', and 'eidos' meaning 'similar', with the intention to show Strongyloides was close to the genus Strongylus.

The Strongyloides genus of nematodes represent one of the soil-transmitted helminthiases (STH), a WHO-recognized neglected tropical disease in humans. Of the estimated 30-100 million human infections, most are asymptomatic. However, people with an altered immune status, particularly because of administration of corticosteroids or HTLV-1 infection, can develop more intense infections resulting in hyperinfection, which can be fatal if not recognized.7

The validity of S. tumefaciens as a species has re-cently been called into question by a 2019 report de-scribing six cats with colonic nodules contain-ing nematodes that based loca-tion and histo-logic character-istics were con-sistent with S. tumefaciens, such as in this case. However, the report's authors determined the nematodes to be S. stercoralis based on sequencing analysis of a portion of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene. This report generated dis-cussion amongst participants, with the moderator advising that genes are largely conserved within genera and unique histologic characteristics of S. tumefaciens, such as a larger egg size, supports S. tumefaciens's validity as a species.

S. stercoralis classically results in the formation of characteristic nodules in the proximal small intestine and is known to infect dogs, cats, non-human primates, and humans.8 S. felis, and S. planiceps have also been described in the proximal small intestine while S. tumefaciens has been described in the colon.

Each species within genus Strongyloides share similar morphologies, however, there variations as previously noted. For example, S. stercoralis, S. felis, and S. tumefaciens have straight ovaries while S. planiceps has spiraled ovaries. Both S. stercoralis and S. felis rhabditiform (L1) larvae are found in the feces while larvated eggs are found in the feces of animals infected with S. planiceps. Parasitic females of each species have a bluntly pointed tail.8

The topic of crypt herniation was also discussed amongst participants, particularly in regard to extension of hyperplastic crypts extending into underlying gut associated lymphoid tissue (i.e. Peyer's patches or GALT). The aforementioned report evaluated similar findings associated with lymphocytic populations within the lamina propria and submucosa. In this report, the authors determined via immunohisto-chemical staining that the majority of cells in all Strongyloides-associated nodules were immunopositive for CD3 (T-cells) and likely indicates these lymphoid nodules are part of an efferent T-cell dominated immune response against the nematodes rather than herniation into preexisting GALT. However, it is also possible that the presence of nematodes within GALT downregulates signals for B-cells, resulting in altered composition of the nodules. Although this phenomenon hasn't been described in Strongyloides spp., other parasites have been shown to produce proteins that interact with human B-lymphocytes and may play a rule in suppression of molecules resulting in activation of B-lymphocytes.8

References:

2. Malone JB, Butterfield AB, Williams JC, Stuart BS, Travasos H. Strongyloides tumefaciens in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1977 Aug 1;171:278?280.

3. Moura MAO, Jorge EM, Nascimento KKG do, et al. Colonic epithelial nodular hyperplasia associated with strongyloidiasis in cats in the Amazon region, Pará State, Brazil. Ciência Rural. 2017;47:1?4.

4. Price EW, Dikmans G, Others. Adenomatous tumors in the large intestine of cats caused by Strongyloides tumefaciens n. sp. Proc Helminthol Soc Wash. 1941;8.

5. Thamsborg SM, Ketzis J, Horii Y, Matthews JB. Strongyloides spp. infections of veterinary importance. Parasitology. 2017;144(3):274-284.

6. Uzal FA, Plattner BA, Hostetter JM. Chapter 1 Alimentary system. In: Maxie GM, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of domestic animals volume 2, sixth edition. 2015:1?257. (updated superscript in the contributor's comment)

7. Viney M. Strongyloides. Parasitology. 2017;144(3):259-262.

8. Wulcan JM, Dennis MM, Ketzis JK, Bevelock TJ, Verocai GG. Strongyloides spp. in cats: a review of the literature and the first report of zoonotic Strongyloides stercoralis in colonic epithelial nodular hyperplasia in cats. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12(1):349.