Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

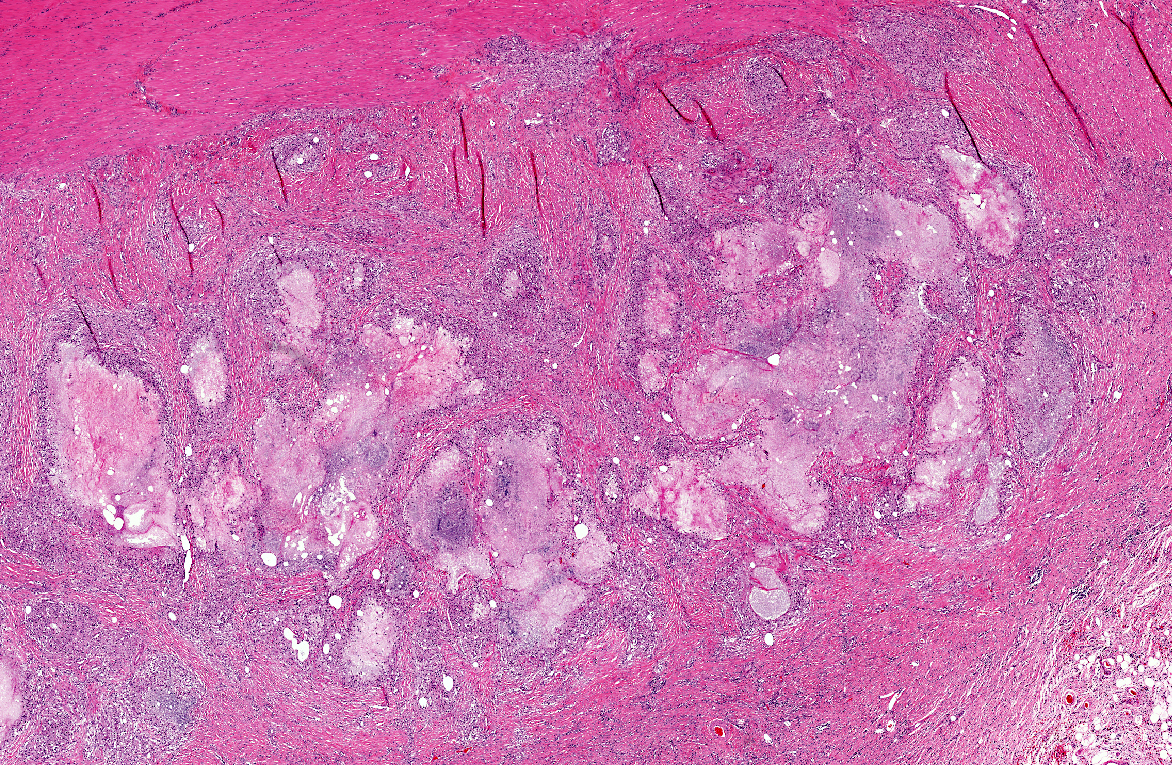

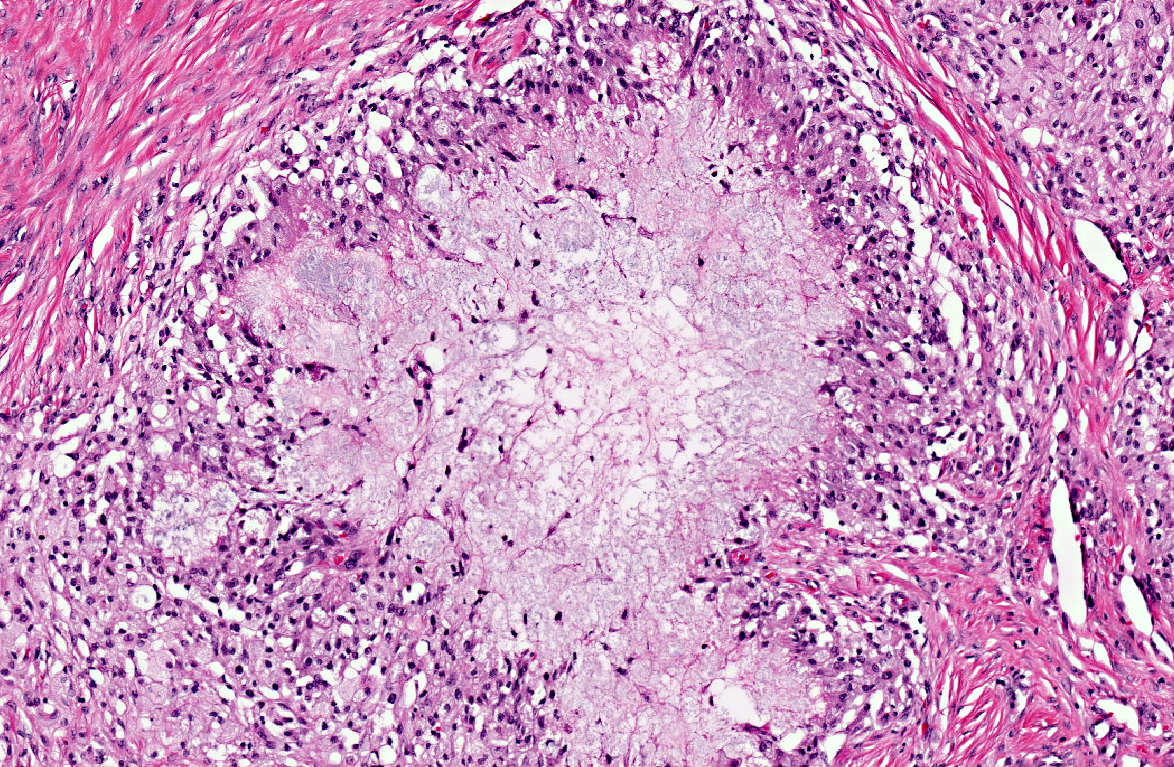

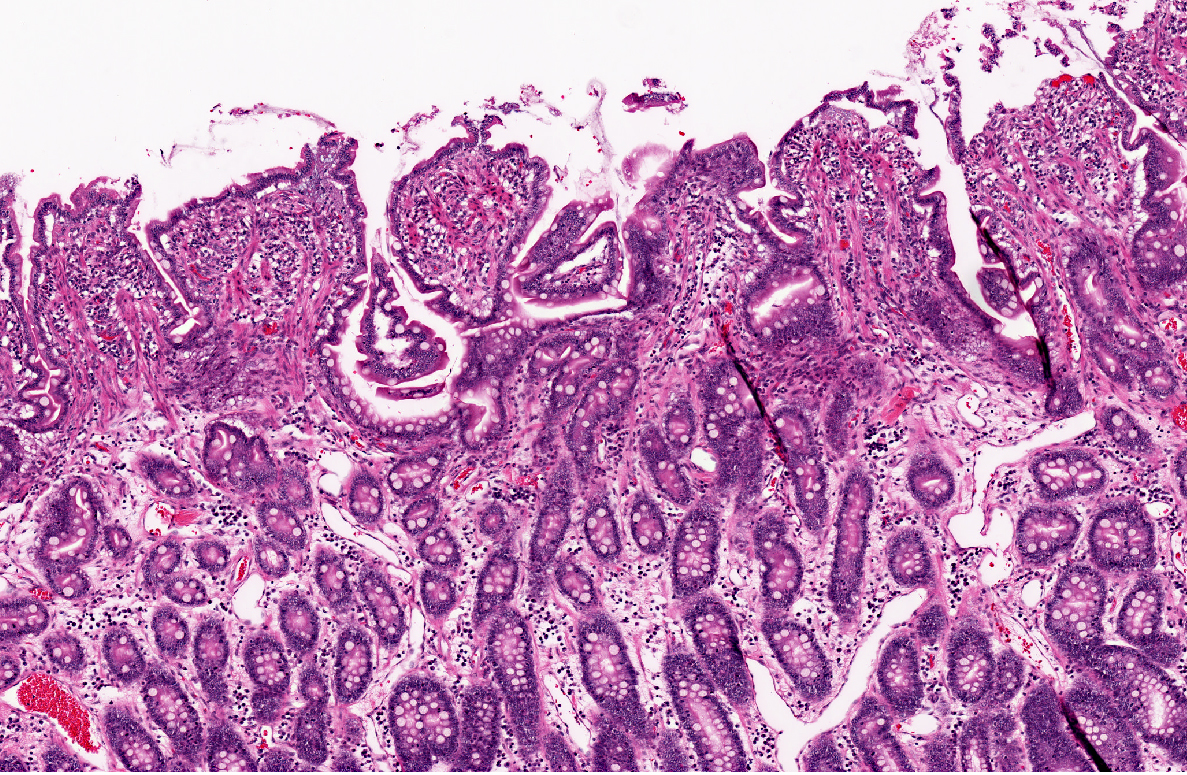

The entire wall of the small intestine is thickened by up to 3 times due to severely congested lymphatics and multifocal necrotic areas with a width of up to 0.5 cm and proliferation of granulation tissue in the lamina and tunica muscularis and the mesentery. The necrotic areas consist of a foamy, slightly granular, protein rich fluid in the center, surrounded by numerous lipid-laden macrophages (lipophages) with a foamy appearance in their cytoplasm. The periphery is marked by infiltration of moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells, few neutrophils and marked proliferations of fibroblasts with broad collagen bundles. The collagen bundles lay perpendicular to the many newly formed capillaries (granulation tissue).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Lymphangitis, lipogranulomatous, severe, multifocal with moderate granulation tissue formation.

Jejunitis, neutrophilic and eosinophilic, mild diffuse.

Lab Results:

The animal had a slightly distended abdomen with a small amount of free, accumulated fluid. The fluid was characterized by a specific gravity of 1.015, protein content of 10 g/L and nucleated cell count of 7475 Lc/μl. The leukocytes consisted mainly of viable neutrophils (95%), few lymphocytes (2%) and monocytes/macrophages (3%). No bacteria could be found within the fluid.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In our case, the lacteals within the villar tips are not the prominent feature, although the villi are shortened and the crypts elongated. The main feature of the lesion is the occurrence of numerous lipogranulomas in the mucosa and mesentery. These lipogranulomas occur adjacent to dilated mesenteric lymphatics, but are not usually a consistent feature of lymphangiectasia(2,3,4,6). They are often considered as secondary lesions due to lymphatic hypertension and fat leakage and to subsequent granulomatous reponse(3,4). Similar granulomas occurred in experimental chronic lymphatic obstruction in rats lacking in lymphatic recanalization.(4) Experimental ligation of lymph vessels in the dog did not cause an inflammatory reaction or granuloma formation.

The cause of lymphangiectasia is not always clear. Some cases appear to be acquired by a chronic inflammatory bowel disease, malignant lymphoma or granulomatous infiltrates but in others, neither a congenital or acquired obstruction of the lymphatic system nor an increase in the inflammatory population of cells in the bowel wall can be seen. This suggests the etiology of the clinical syndrome might be more complex than simple obstruction of the lymphactics(4).

In Basenjis and Soft Coated Wheaten Terriers (SCWT), a familial predisposition for both protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) and protein-losing nephropathy (PLN) is suspected. However Basenjis differ from SCWT in their clinical presentation. In Basenjis, PLN was not seen separately without intestinal lesions, whereas PLN occurred alone in the SCWT(2).

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Clinical pathology abnormalities often associated with lymphangiectasia include panhypoproteinemia, which is seen in severe disease with failure of compensatory plasma protein production; lymphopenia, due to loss in lymphatic fluid or stress; hypocholesterolemia; and hypocalcemia. Hypocalcemia is attributed to hypoalbuminemia, and the majority of dogs have serum calcium levels in the normal reference range after correction for albumin(5); however, some dogs develop ionized hypocalcemia, which may be the result of vitamin D malabsorption, seen commonly with lymphangiectasia(1).

As mentioned by the contributor, the lesions in this case largely spare the mucosa and lack the dilation of lacteals classically described in lymphangiectasia-derived protein-losing enteropathy. As such, this case illustrates a major limitation of surgical mucosal biopsy, which would have failed to sample the diagnostic lesions in the submucosa and outer tunics. The conference moderator emphasized the distinction between lipogranulomatous lymphangitis and lipogranulomas. In two-dimensional cross section, an inflamed lymphatic vessel may appear as a characteristic discrete granuloma with the four typical layers (i.e. central necrosis surrounded by histiocytes, fibrosis, and lymphocytes); however, since the inflammation is actually tracking lymphatics, the term lipogranulomatous lymphangitis may be preferable to lipogranuloma.

References:

2. Littman M.P.; Dambach D.M.; Vaden S.L.; Giger U.: Familial Protein-losing Enteropathy and Protein-losing Nephropathy in Soft Coated Wheaten Terriers: 222 Cases (1983-1997). J. Vet Intern Med; 14:68-80 (2000).

3. Maxie M.G. In Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals: Malassimilation and Protein-losing syndromes. 5th Ed, Vol.2:102-104 (2007)

4. Suter M.M.; Palmer D.G.; Schenk H.: Primary Intestinal Lymphangiectasia in Three Dogs: A Morphological and Immunopahtologial Investigation. Vet. Pathol.22: 123-130 (1985).

5. Tarpley HL, Bounous DI. Digestive System. In: Latimer KS ed. Duncan & Prasses Veterinary Laboratory Medicine Clinical Pathology. 5th ed. Ames, IA:Wiley-Blackwell; 2011:242-5.

6. Van Kruiningen H.J.; Lees G.E.; Hayden D.W.; Meuten D.J.; Rogers W.A.: Lipogranulomatous Lymphangitis in Canine Intestinal Lymphangiectasia. Vet. Pathol. 21:377-383 (1984).