Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

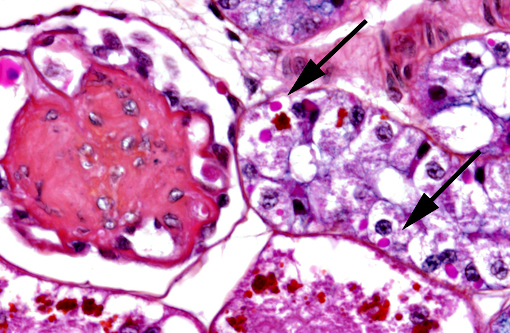

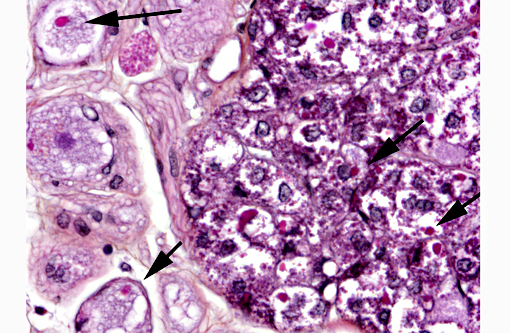

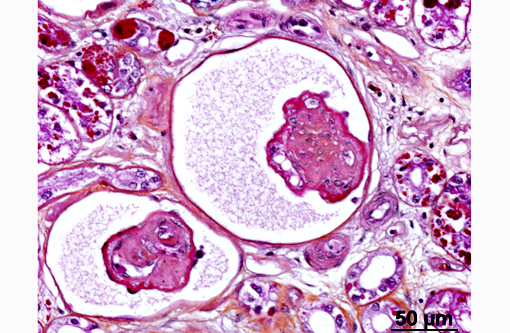

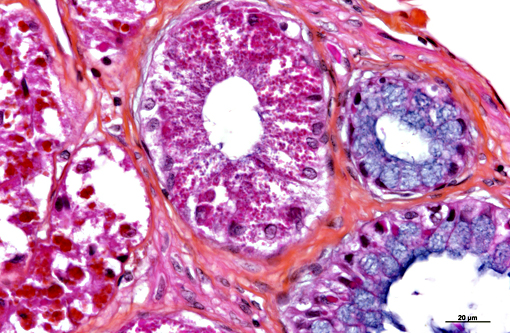

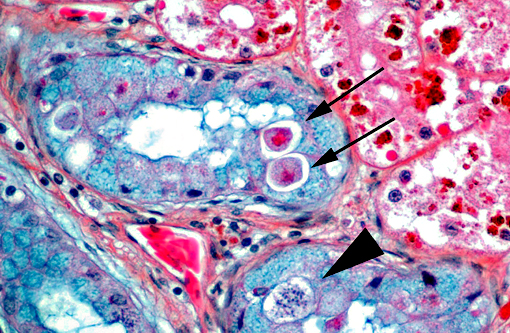

In the kidney, almost all glomeruli show abundant collagen deposition within the mesangium (glomerulosclerosis). Some glomeruli show cystic atrophy. Rare lymphocytes and heterophils infiltrate the interstitium. Numerous intensely eosinophilic and tightly packed 2-μm granules are present in nephrocytes of the distal convoluted tubules (sexual segment) whereas epithelium of the proximal convoluted tubules contain coarsely granular brownish pigments (see discussion).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Kidney:

1) Numerous intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions within renal tubular epithelium, consistent with inclusions of Inclusion Body Disease.

2) Glomerulosclerosis, diffuse, severe with rare glomerular cystic atrophy.

3) Numerous brownish cytoplasmic pigments of unknown significance within epithelium of the proximal convoluted tubules.

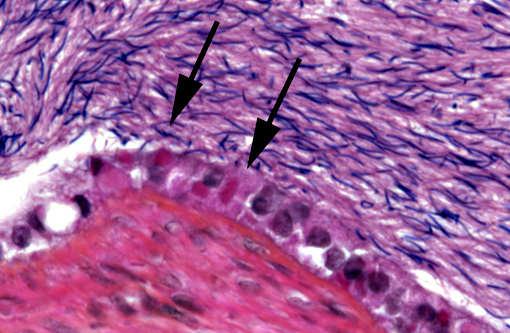

4) Epididymis: Numerous intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions within epididymal epithelium, consistent with inclusions of Inclusion Body Disease.

5) Nervous ganglia: Numerous intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions with neurons and chromaffin cells, consistent with inclusions of Inclusion Body Disease.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Arenaviruses are negative single-stranded RNA viruses. Their genome contains two elements: small (S) and large (L). The S segment encodes the viral nucleocapsid protein and the glycoprotein while the L segment encodes the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and a small ring-domain-containing protein.(3) The genus arena virus is the only genus of the Arenaviridae family and comprises 25 species according to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV, 2014). Two major lineages of arenaviruses are described based on genetic differences and geographical distribution: Old World arenaviruses and New World arena viruses.(3,5)

In humans, arenaviruses cause hemorrhagic fevers (Lassa, Junin, Machupo, Guanarito, Sabia and Chapare viruses) and lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCM) due to LCM virus. Asymptomatic infections also occur.(6)

The LCM virus can also produce congenital malformations and has been recently described as an important cause of fatal infection in organ transplantations recipients and immunocompetent patients.(6) LCM virus has a wide range of hosts: humans, hamsters, guinea pigs, cotton rats, chinchillas, canids and primates.(11) Mus musculus is considered the natural reservoir host. In New World primates of the Callitrichidae family (marmosets, tamarins), LCM virus causes callitrichid hepatitis.(11)

In boids, IBD does not manifest similarly between boas and pythons. Boas usually show intermittent regurgitation followed by anorexia. After a few weeks, neurologic signs appear and are characterized by head tremor, disorientation, ataxia, opisthotonos and behavioral changes.(14,16) Pneumonia and necrotizing stomatitis are common complications. After a few weeks or months of progression, death occurs.(13) Pythons do not display regurgitation but are often anorectic. Neurologic signs occur earlier in pythons than in boas, and are more severe. The progression is more rapid and death occurs after a few weeks.(4,14)

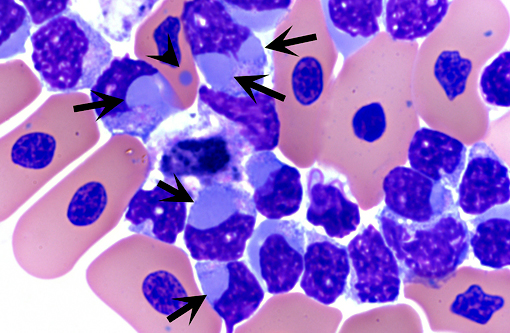

Historically, the diagnosis of IBD relied on the demonstration of characteristic eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions on histological sections. In pythons, these inclusions are mostly found in the neurons of the central nervous system.(4) In boa constrictors, inclusions are commonly seen, in addition to neurons and glial cells of the central nervous system, in esophageal tonsils (epithelium and lymphoid cells), gastrointestinal and respiratory epithelia, hepatocytes, pancreatic acinar cells and renal tubular epithelium.(4) Inclusions can also be demonstrated on blood smears and/or impression smears of organs (liver and kidney). Such smears can be stained with Wright-Giemsa stain but H&E stain can also be used and appears more sensitive.(4) On blood smears, inclusions can be demonstrated in erythrocytes, lymphocytes and heterophils.(4) Tissues for diagnosis can be obtained from necropsy samples but antemortem diagnosis is also possible through esophageal tonsil, liver or renal biopsies.(4) As the number and distribution of inclusions is variable, with boas having more inclusions than pythons, diagnosis relying on identification of inclusion bodies is not a very sensitive method. Furthermore, inclusions can be found in other diseases.(4) With the recent discovery of IBD virus, a definitive and more sensitive diagnosis is now possible through PCR testing.

In this case, inclusion bodies were found in a large number of tissues as well as in cells from coelomic effusion, allowing antemortem diagnosis. PCR testing confirmed infection by IBD virus. In the kidney, renal epithelial cells also contained variable-sized acidophilic granules and brownish pigments. The acidophilic granules are typical to adult males of some snake and lizard species. They are present in the distal convoluted tubules, referred to as the sexual segment. The content of the granules is extruded into the urinary wastes and is believed to represent pheromones that are useful for sexual courtship and mating.1 The brownish pigments are of unknown origin and significance. They were negative for Prussian blue stain, Schmorls stain and PAS stain.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Epithelial cells of renal tubules, ureter, and epididymis and neurons: Intracytoplasmic protein droplets, numerous.

2. Kidney: Glomerulosclerosis, diffuse, moderate.

3. Kidney, tubular epithelium: Brown pigment of unspecified origin.

4. Kidney, tubular epithelium: Intracytoplasmic apicomplexans, few

Conference Comment:

The contributor highlights the recent identification of an arenavirus as the cause of IBD. The characteristic cytoplasmic inclusions associated with IBD are dramatic and found in many tissues usually in the absence of inflammation.(4) Typically, viral inclusions are the result of viral nucleic acid templates liberated in the cytoplasm which are utilized by the host cell to produce aberrant production of viral proteins. These proteins are often produced in excess and subsequently accumulate as inclusion bodies. While most viral inclusions are composed of excess viral proteins and membranes with viral particles, some consist of mature viral particles (virions) arranged in lattice formations.(7) IBD inclusions are nonviral, composed exclusively of 68-KDa protein deposited by ribosomes(10) which may have hindered prompt identification of the virus.

The observation of viral protein inclusions and brown pigment within the tubular epithelium was further complicated by the prominent acidophilic granules common in male reptiles as discussed by the contributor. It is worth mentioning this snake was in its reproductive season at the time of necropsy as the granules are prominent and sperm production is abundant.

The presence of glomerulosclerosis is a common finding in older reptiles; and we chose to separate its diagnosis as most did not feel it was related to the viral infection. Glomerulosclerosis is characterized by shrunken and hyalinized mesangium, with an increase in fibrous connective tissue and a loss of capillaries. Tubular degeneration often occurs secondarily, as they receive their blood supply from the glomerular efferent arteriole which becomes compromised in these instances. Glomerulosclerosis is accelerated by inflammation, excessive dietary protein and increased glomerular capillary pressure.(12) Its widespread occurrence in reptiles is most often attributed to high protein diets.(8)

Rarely observed in a few sections and confined to one small area of renal tubules, there are few intraepithelial organisms closely resembling an undetermined species of coccidia which gave us a fourth diagnosis to contribute.

References:

1. Aughey E, Frye FL. Urinary System. In: Comparative Veterinary Histology with Clinical Correlates. 1st edition. London: CRC Press; 2001:137-148.

2. Bodewes R, Kik MJL, Raj VS, et al. Detection of novel divergent arenaviruses in boid snakes with inclusion body disease in The Netherlands. J Gen Virol. 2013; 94:120610.

3. Buchmeier M, de la Torre J, Peters C. Arenaviridae. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Fields Virology. 5th edition. New York, NY: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1791828.

4. Chang L-W, Jacobson ER. Inclusion Body Disease, A Worldwide Infectious Disease of Boid Snakes: A Review. J Exotic Pet Med. 2010; 19:21625.

5. Charrel RN, de Lamballerie X, Emonet S. Phylogeny of the genus Arenavirus. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008; 11:3628.

6. Charrel RN, de Lamballerie X. Zoonotic aspects of arenavirus infections. Vet Microbiol. 2010; 140:21320.

7. Cheville NF. Ultrastructural Pathology The Comparative Celullar Basis of Disease. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2009:851.

8. Hernandez-Divers S, Innis CJ. Renal disease in reptiles: diagnosis and clinical management. In: Mader DR, ed. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:879.

9. Hetzel U, Sironen T, Laurinm+â-ñki P, et al. Isolation, identification, and characterization of novel arenaviruses, the etiological agents of boid inclusion body disease. J Virol 2013; 87:1091835.

10. Jacobson ER. Viruses and viral diseases of reptiles. In: Jacobson ER, ed. Infectious Diseases and pathology of reptiles. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007:410-412.

11. Montali RJ, Connolly BM, Armstrong DL, Scanga CA, Holmes KV. Pathology and immunohistochemistry of callitrichid hepatitis, an emerging disease of captive New World primates caused by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Am J Pathol. 1995; 147:14419.

12. Newman SJ. The Urinary system. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012:626-627.

13. Percy DH, Barthold SW. The mouse. In: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd edition. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2007:3-124.

14. Schumacher J, Jacobson ER, Homer BL, Gaskin JM. Inclusion Body Disease in Boid Snakes. J Zoo Wildl Med. 1994; 25:51124.

15. Stenglein MD, Sanders C, Kistler AL, et al. Identification, characterization, and in vitro culture of highly divergent arenaviruses from boa constrictors and annulated tree boas: candidate etiological agents for snake inclusion body disease. MBio. 2012; 3: e0018000112.

16. Vancraeynest D, Pasmans F, Martel A, et al. Inclusion body disease in snakes: a review and description of three cases in boa constrictors in Belgium. Vet Rec. 2006; 158:75760.