WSC 2023-2024, Conference 22, Case 2

Signalment:

9-year-old female Tinker horse (Equus caballus)

History:

A mature female horse was admitted to the vet with hematuria. Bloodwork showed a hypoalbuminemia. The clinical signs improved after treatment with antibiotics and anti-helminthics. 3 weeks later, the horse developed a fever and ataxia. Treatment with doxycycline and NSAIDs was started, but one day later the horse was in lateral recumbency and had a vertical nystagmus. It was humanely euthanized.

Gross Pathology:

The horse was in a good body condition with normal musculature and normal fat reserves. Both kidneys contained multifocal, pale, firm, well-circumscribed masses varying in size from 1 to 10 cm in diameter. The mammary glands contained a moderate amount of watery, yellow fluid and were diffusely light pink on cut surface. Multifocally, the back muscles and gluteal muscles were diffusely pale compared to the other muscles.

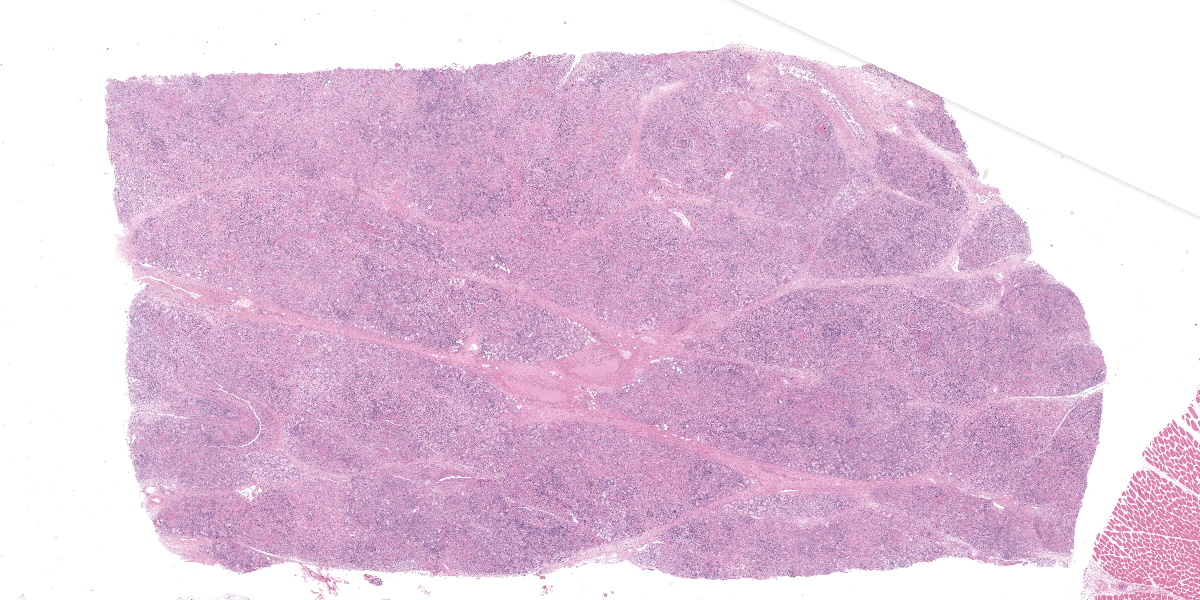

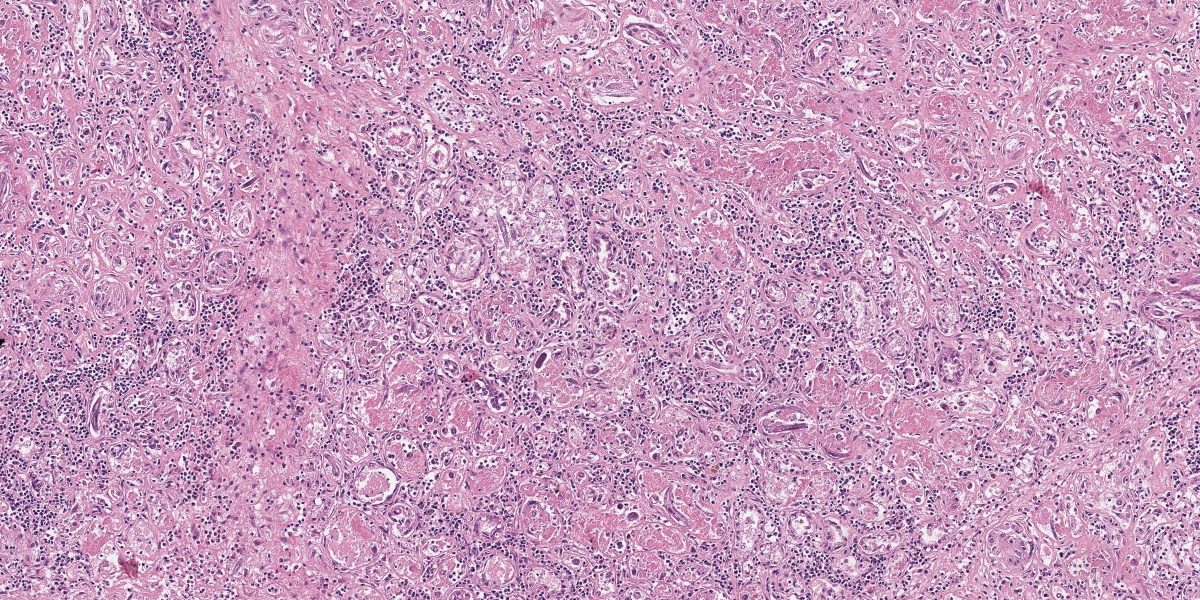

Microscopic Description:

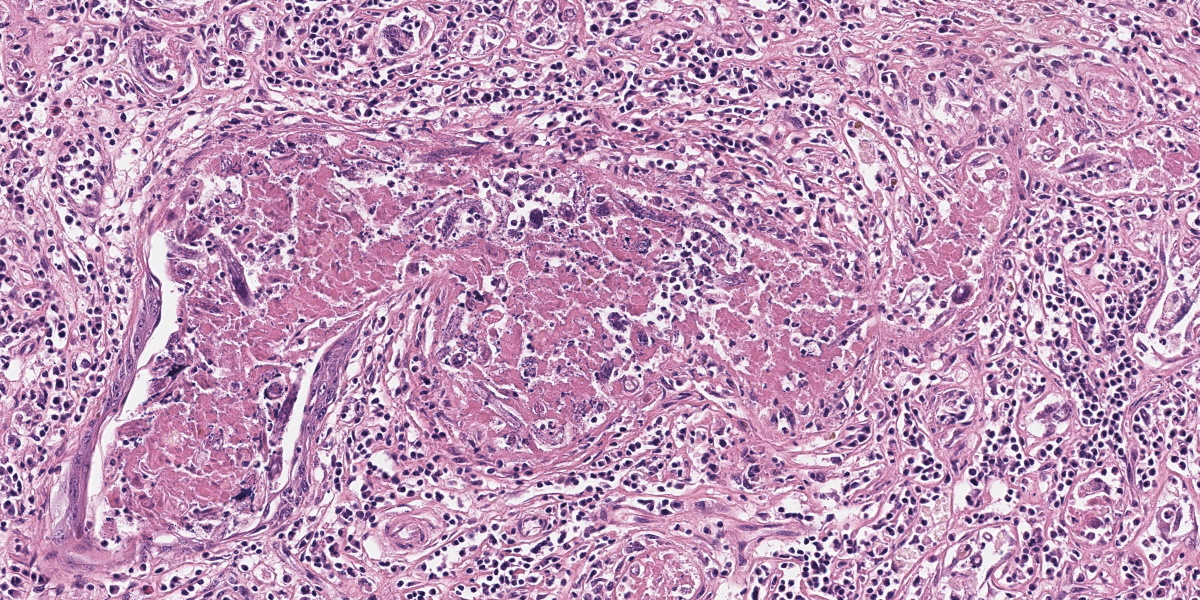

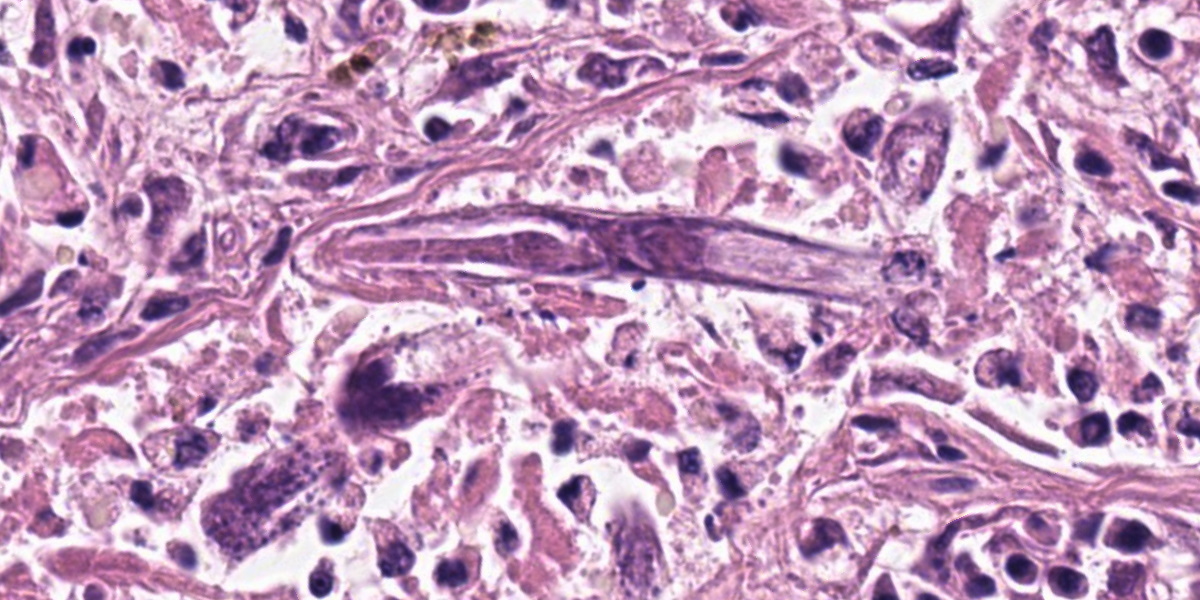

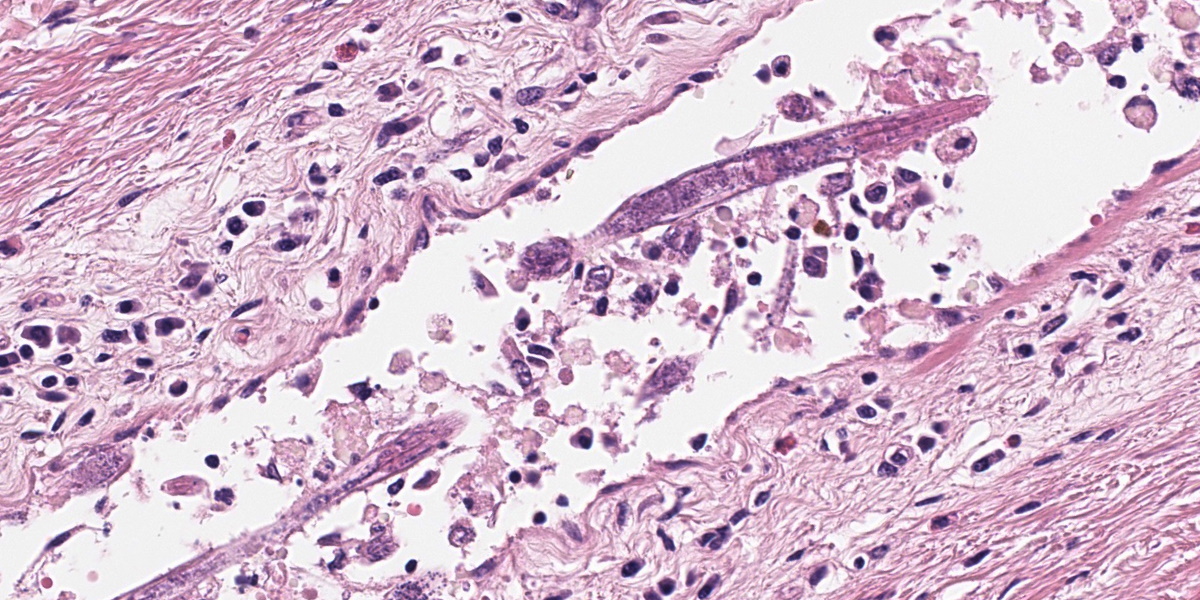

Mammary gland: Multifocally to coalescing, the original tissue architecture is extensively disrupted by foci of granulomatous inflammation, characterized by large numbers of epithelioid macrophages and few multinucleated giant cells (Langhans-type), admixed with large numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils. The inflammation is centered around sections of nematode adults, larvae, and eggs, which are randomly spread throughout the tissue. The adult nematodes are approximately 15-20 microns in diameter and up to 300-400 microns in length, and have a thin cuticle, platymyarian-meromyarian musculature, intestinal tract, and characteristic rhabditiform esophagus with a corpus, isthmus and terminal bulb. The nematode larvae measure 10-15 microns in diameter and 150-250 microns in length and have a rhabditiform esophagus. Nematode eggs are ovoid, both embryonated and larvated, and measure approximately 10 x 50 microns. Incidentally, parasites are surrounded by karyorrhexis and karyolysis, with loss of cell detail (lytic necrosis).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Mammary gland: Severe, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, granulomatous, eosinophilic and lymphoplasmacytic mastitis with myriad intralesional rhabditoid nematode adults, larvae, and eggs, etiology presumptive Halicephalobus gingivalis.

Contributor’s Comment:

The parasite with its accompanying inflammation was also extensively present in the cerebrum, cerebellum, kidneys and some skeletal muscles.

Halicephalobus gingivalis is a facultative, opportunistic nematode of the order Rhabditidia, family Panagrolaimidae, and causes a rare form of meningoencephalomyelitis in equids, humans, and ruminants.4,5 The life cycle and pathogenesis of this opportunistic pathogen is still poorly understood. Halicephalobus nematodes are found free-living in association with water, soil, and decaying organic matter and it is thought that transmission occurs primarily via wounds in the skin or mucous membranes.3 Rarely, other routes of infection have been suggested, including transmammary.

Upon infection, dissemination of the infection is then thought to occur hematogenously.2 Sexual reproduction is believed to occur during the free-living part of the life cycle and although both males and females exist in the environment, only female nematodes have been observed within microscopic lesions. This suggests that within a host, reproduction occurs asexually via parthenogenesis.1 Histologic identification of consistent lesions and morphologically compatible rhabditoid nematodes found postmortem are an indication for diagnosis, although the nematodes can be extracted from fresh tissue or the parasite can be shed in the urine if there is renal involvement.

Contributing Institution:

Veterinair Pathologisch Diagnostisch Centrum

University of Utrecht

https://www.uu.nl/onderzoek/veterinair-pathologisch-diagnostisch-centrum

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Mammary gland: Mastitis, granulomatous and eosinophilic, chronic, diffuse, marked, with numerous adult and larval rhabditid nematodes.

2. Lymph node: Reactive hyperplasia, diffuse, moderate.

JPC Comment:

Halicephalobiasis is an infection characterized by localized or disseminated granulomatous lesions that has been sporadically reported in horses and zebras and less commonly in cows and humans.6 As the contributor notes, surprisingly little is known about the pathogenesis of the disease and the biology of the causative agent, Halicephalobus gingivalis. The nematode was first described in 1954 after the worms were discovered within a gingival granuloma in a horse, providing the species name for this enigmatic pathogen.5 H. gingivalis has since been described in, among other tissues, the central nervous system, kidneys, oral cavity, eyes, lungs, adrenal glands, spleen, liver, heart, and, with this case, the mammary gland.5,6

Due to the variety of tissues that can be affected, the clinical presentations and signs of halicephalobiasis are highly variable; however neurologic and renal lesions, and their attendant clinical signs, appear to be overrepresented in published case reports.6 The nematode itself has a distinctive morphology, which is nicely demonstrated in the abundant longitudinal and cross sections present in the examined slide. Adult H. gingivalis nematodes are cylindrical with tapered anterior ends and pointed tails, and possess a classic rhabditiform esophagus composed of the canonical corpus, isthmus, and bulb.6

The central nervous system is most commonly affected in horses, with massive intracranial invasion often causing an acute disease with a short course.1 Gross lesions include focal arachnoid hemorrhages and multifocal thickening of the meninges. Histologically, female nematodes and larvae are found within lesions, particularly in perivascular spaces, and lesions are characterized by granulomatous and eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, myelitis, or polyradiculitis; parasitic granulomas in the kidneys and gingiva often accompany, and are perhaps antecedent to, central nervous system invasion.1 Treatment of H. gingivalis infection is typically ineffective, most likely due to the inability of drugs such as ivermectin to penetrate the robust granulomatous lesions or to cross the blood-brain barrier; thus, these infections typically have a poor prognosis and a short course.6 Other rhabditid nematodes that can infect horses include Strongyloides westeri, Pelodera strongyloides (more commonly associated with cutaneous lesions in dogs), and Cephalobus spp.; however, the size and distinct morphology of H. gingivalis allow for a presumptive diagnosis.6

Dr. Stromberg challenged conference participants, who all agreed with the contributor’s identification of Halicephalobus gingivalis, to consider their level of confidence in their parasite identification. Considering the large number of rhabditid nematodes that exist in the environment, how does one know definitively that this nematode is H. gingivalis, particularly given the unusual anatomic location in which this nematode is found? Additionally, the extremely small size of the parasite makes evaluation of fine anatomic features, such as the type of musculature present, particularly challenging. The moderator, while agreeing with the etiology and diagnosis, urged conference participants to at least acknowledge when a diagnosis is based on probability; while, by definition, a probability-based identification is often correct, it behooves the diagnostic pathologist to realize that these diagnoses deserve extra scrutiny.

Dr. Stromberg noted that the intensity of the inflammatory response evoked by a particular parasite can give insight into the evolutionary history of the parasite/host relationship. In this case, the typically robust inflammatory response suggests that the evolutionary history of H. gingivalis and the horse is short and still being written. The raging chronic mastitis is evidenced by a range of fibrosis throughout the mammary gland, which conference participants appreciated by examination of a Masson trichrome stain. Dr. Stromberg noted the correlation between the degree of damage and fibrosis and the number of adult and larval nematodes in a particular area, with fibrosis ranging from barely perceptible to obliterative in the most severely affected sections.

The JPC morphologic diagnosis omits a specific etiology, preferring, based on Dr. Stomberg’s discussion of uncertainty, to describe the parasite simply as a rhaditid nematode. Participants also felt that the changes observed in the accompanying lymph node were severe enough to warrant their own mention.

References:

- Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016:390.

- Henneke C, Jespersen A, Jacobsen S. The distribution pattern of Halicephalobus gingivalis in a horse is suggestive of a haemotogenous spread of the nematode. Acta Vet Scand. 2014;56:1-4.

- Hermosilla C, Coumbe KM, Habershon-Butcher J, Schöniger S. Fatal equine meningoencephalitis in the United Kingdom caused by the panagrolaimid nematode Halicephalobus gingivalis: case report and review of the literature. Equine Vet J. 2011;43:759-763.

- Lim CK, Crawford A, Moore CV, et al. First human case of fatal Halicephalobus gingivalis meningoencephalitis in Aust-ralia. J Clin Microb. 2015;53(5):1768-1774.

- Onyiche TE, Okute TO, Oseni OS, et al. Parasitic and zoonotic meningoence-phalitis in humans and equids: Current knowledge and the role of Halicephalobus gingivalis. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2018;3(1):36-42.

- Pillai VV, Mudd LJ, Sola MF. Dis-seminated Halicephalobus gingivalis infection in a horse. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2023;35(2):173-177.