CASE 1: 17N00143 (4117640-00)

Signalment:

16-year-old, castrated male, Brittany Spaniel, Canis familiaris, dog

History:

In June 2013 the animal was diagnosed via echocardiogram by an outside cardiology service with a right atrial mass that appeared to originate from the atrial septum, initially the mass measured approximately 1.5 cm in diameter. The animal was evaluated yearly by a cardiologist and at his most recent appointment in July 2016, the mass was noted to be taking up 80% of his right atrium. Before the diagnosis of the atrial mass and through the course of his disease, the animal had a history of ventricular arrhythmia, paroxysmal atrial tachycardia and mild pulmonary hypertension. Eight months after his last appointment with the referral cardiologist the animal stopped eating, became lethargic, was vomiting and coughing. He presented to his primary care veterinarian where he was found to have fluid in his abdomen. The animal was humanely euthanized and presented to UW Veterinary ER service for necropsy.

Gross Pathology:

On gross examination, there was a multilobulated, pink-tan to red, semi-firm mass extending from the endocardial surface of the right atrium measuring approximately 7.0 x 8.0 x 3.5 cm. There was a single separate dark red to black nodule on the endocardial surface at the base of the right atrial appendage, which measured 0.9 x 0.7 x 0.5 cm. A mass with a necrotic center was also present in the left ventricular wall measuring 14 mm in diameter. On cut section, all masses were mottled pale tan to dark red. Additionally there was a focal area of pink to tan discoloration and contracture on the papillary muscle of the left ventricle measuring 0.9 x 0.7 cm. The heart weight 253.4 grams corresponding to approximately 1.7% of the body weight.

Laboratory results:

None.

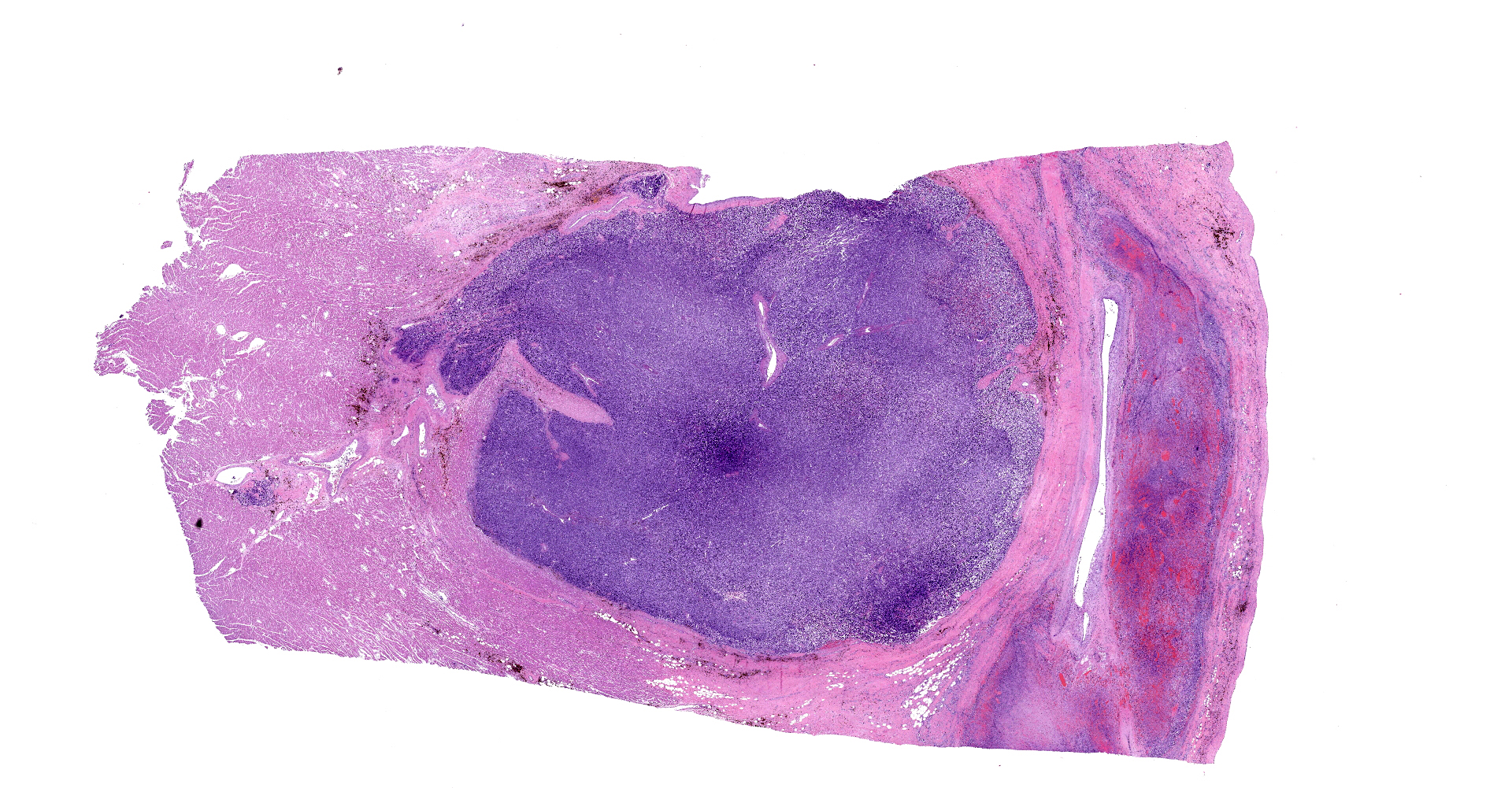

Microscopic description:

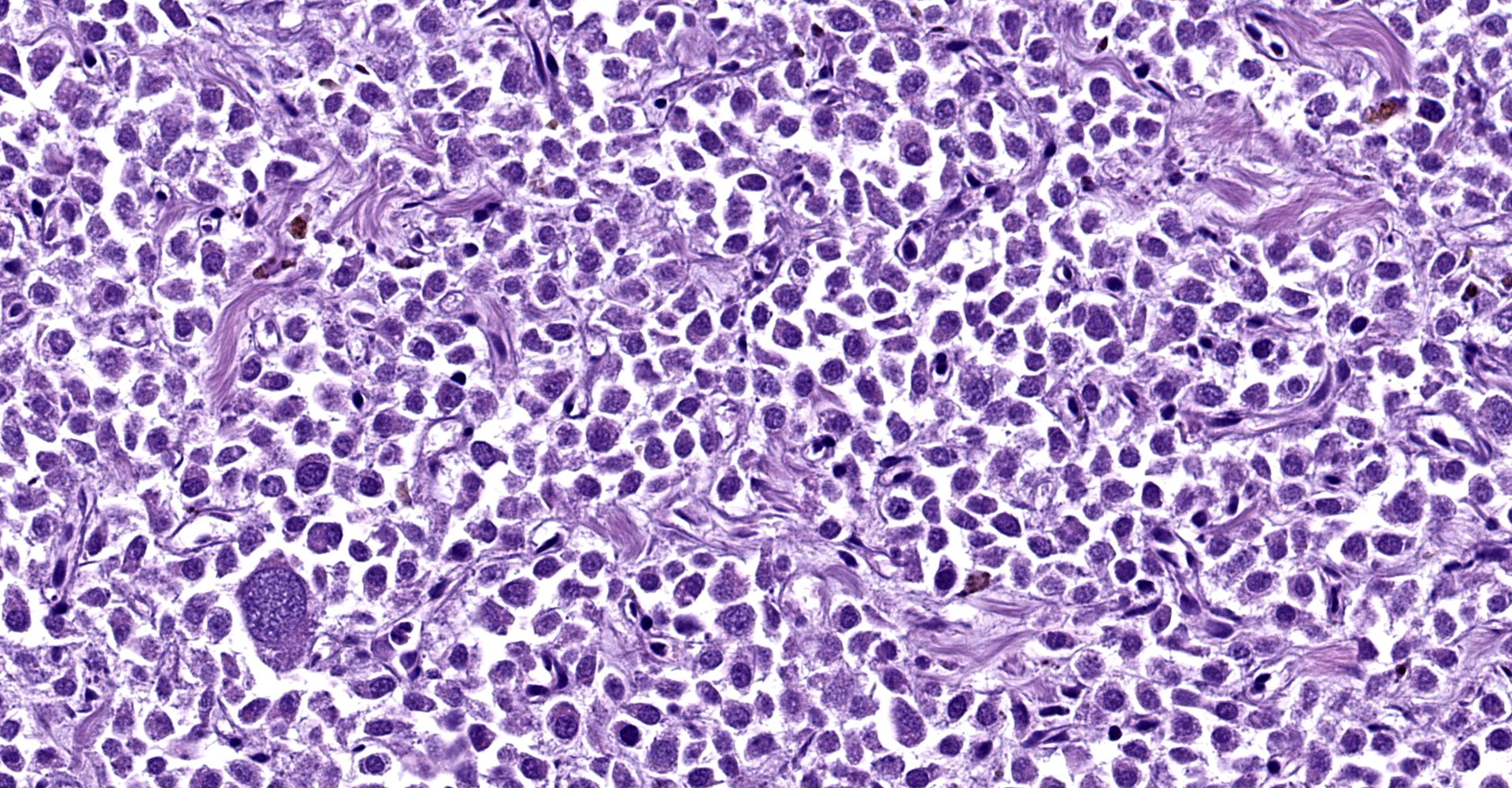

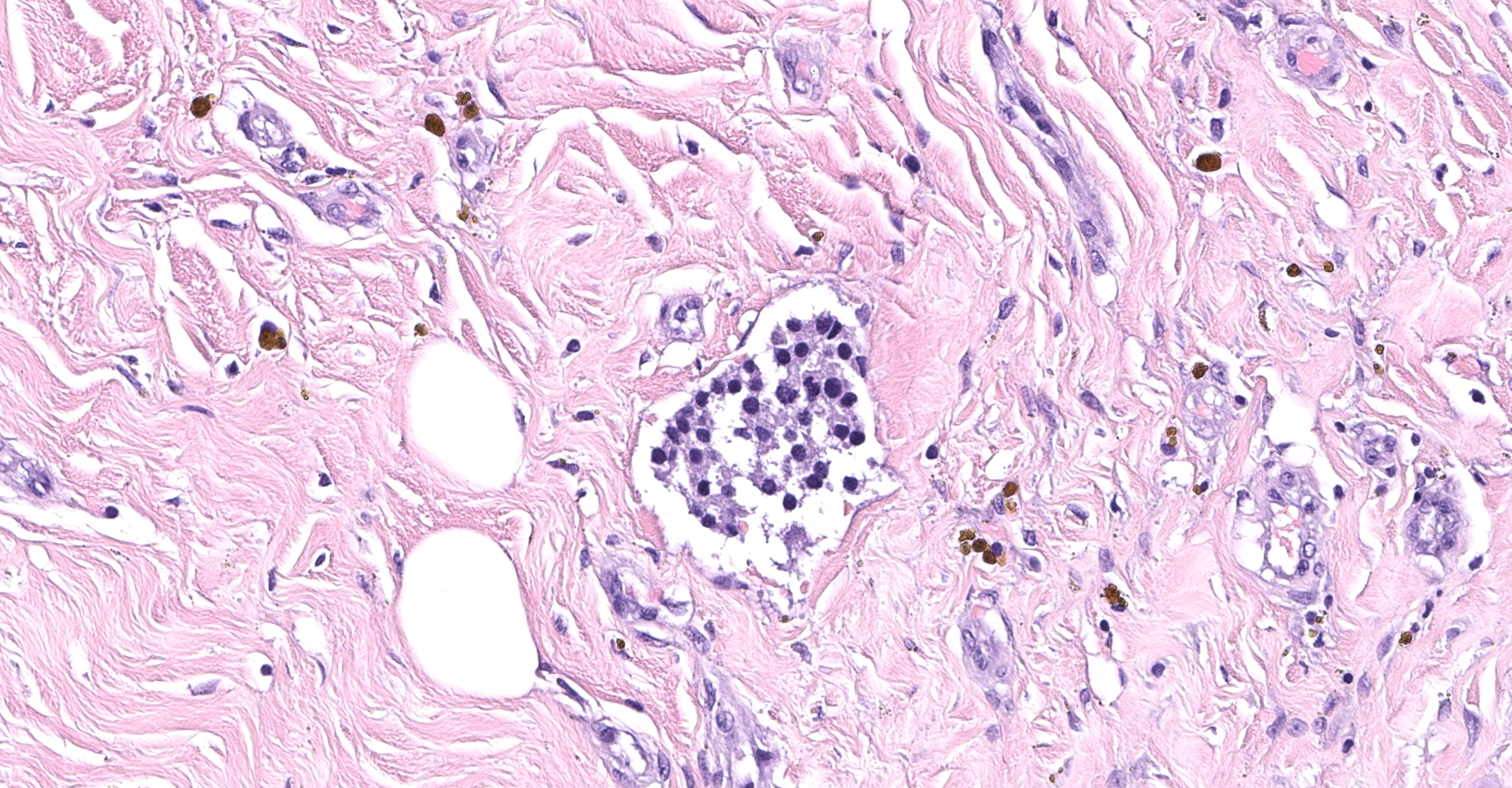

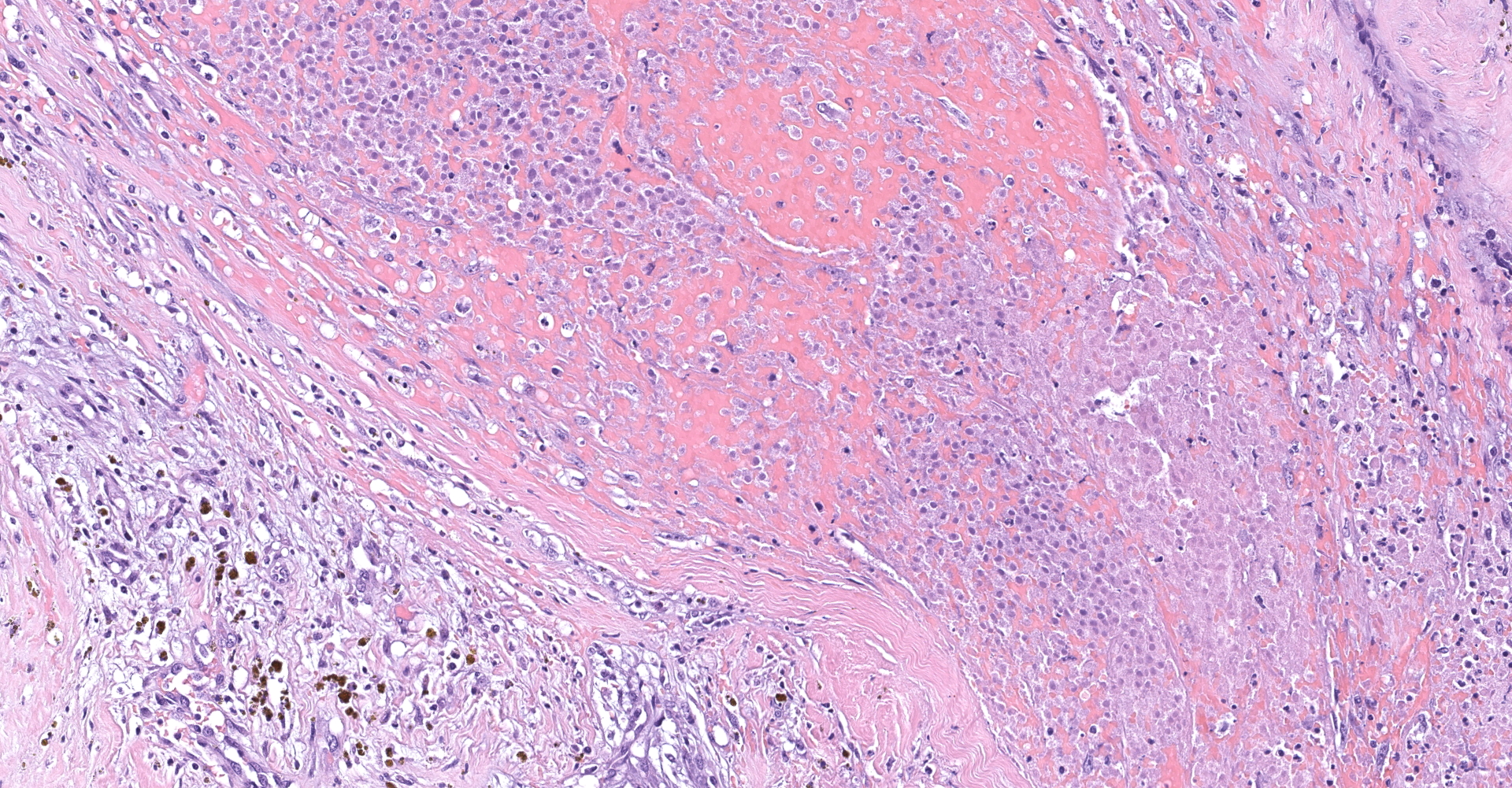

Right atrium: An unencapsulated, moderately well demarcated and moderately cellular neoplasm multifocally infiltrates, expands and effaces the myocardium. The neoplastic cells are arranged in nests, packets and small lobules and are supported by a fine fibrovascular stroma. The cells are round to polygonal with variably distinct cell borders, moderate amounts of finely granular amphophilic cytoplasm and round nuclei with coarsely clumped chromatin and indistinct nucleoli. The cells exhibit moderate to marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis and mitotic figures are present (0-3 mitotic figures per 400x field). Occasional neoplastic cells have large, multilobed nuclei. There are multifocal to coalescing areas of necrosis throughout the mass. Neoplastic cells multifocally occupy and occasionally expand the lumens of blood vessels within the surrounding myocardium. Areas of hemorrhage, fibrosis and hemosiderin-laden macrophages multifocally surround the neoplasm.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Right atrium (per submitter), atrial paraganglioma

Contributor's comment:

Cardiac tumors are relatively uncommon in the canine population.1,4,14,23 The most common type of cardiac tumor is hemangiosarcoma follow by paragangliomas occurring at the heart base (i.e. chemodectomas, also known as aortic body tumors), lymphoma and ectopic thyroid carcinoma.4,15,23

Paragangliomas are neuroendocrine tumors that originate from chromaffin cells that are associated with sympathetic ganglia (for example adrenal medulla pheochromocytoma) or the parasympathetic ganglia (for example aortic body / chemodectoma).8,11,17

Paraganglia are groups of chromaffin neurosecretory cells of neural crest origin located around ganglia that are dispersed throughout the body.5 They are classified as sympathetic or parasympathetic according to their location and neural association.5,7 Sympathetic paraganglia, of which the adrenal medulla is the prime example, are distributed along paravertebral sympathetic chains and nerves that innervate cervical, thoracic, retroperitoneal and pelvic organs.5,7,11 Parasympathetic paraganglia, also referred to as chemoreceptors, are distributed primarily along the cervico-thoracic branches of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves and include the orbital, vagal, laryngeal, and subclavian paraganglia, as well as the carotid and aortic bodies.5,7,11

The unifying feature of sympathetic paragangliomas is the fact that they can be functional and are able to synthesize and secrete significant amounts of catecholamines,7,8,17 whereas parasympathetic paragangliomas tend to be non-functional and don't release catecholamines or if they do, they tend to release dopamine so human or animal patients usually do not present with typical symptoms of catecholamine excess such as systemic hypertension or tachycardia.8,17,18 In veterinary medicine, the most common parasympathetic tumor is the chemodectoma, also known as aortic/carotid tumor or non-chromaffin paraganglioma.4,15,16 However, the latter term is an antiquated and confusing term, considering that all types of paraganglia tumors originate from chromaffin cells and that approximately 40-50% of the parasympathetic tumors are recognized to secrete catecholamine metabolites (such as dopamine) to some extent.17

In human medicine, 95% of all reported sympathetic paragangliomas are pheochromocytomas. Only 2% occur above the diaphragm, which account for 0.3% of all mediastinal/ cardiac neoplasms, and less than 50% of those tumors are functional. In veterinary medicine, the distribution and functionality are very similar.19 Pheochromocytomas are the most common neoplasia arising from the adrenal medulla, they are infrequently functional, and there are only rare case reports of sympathetic cardiac paraganglioma of which two were located in the right atrium and one in the left atrium.2,4,21,23 In contrast, chemodectomas, which were mentioned previously, are the second most common parasympathetic cardiac paraganglioma.4,12,15 The distinction between sympathetic or parasympathetic cardiac tumors should be mainly based on location since there are no consistent histologic differences between them.8,17 Chemodectomas are typically located on the epicardial surface of the heart base along the aortic body or atria and occasionally extend to the atria, or the interatrial septum. Sympathetic cardiac paragangliomas are generally located within the atria along the atrioventricular sulcus and near the roots of the great vessels,4,7,8,17,20 as in this case.

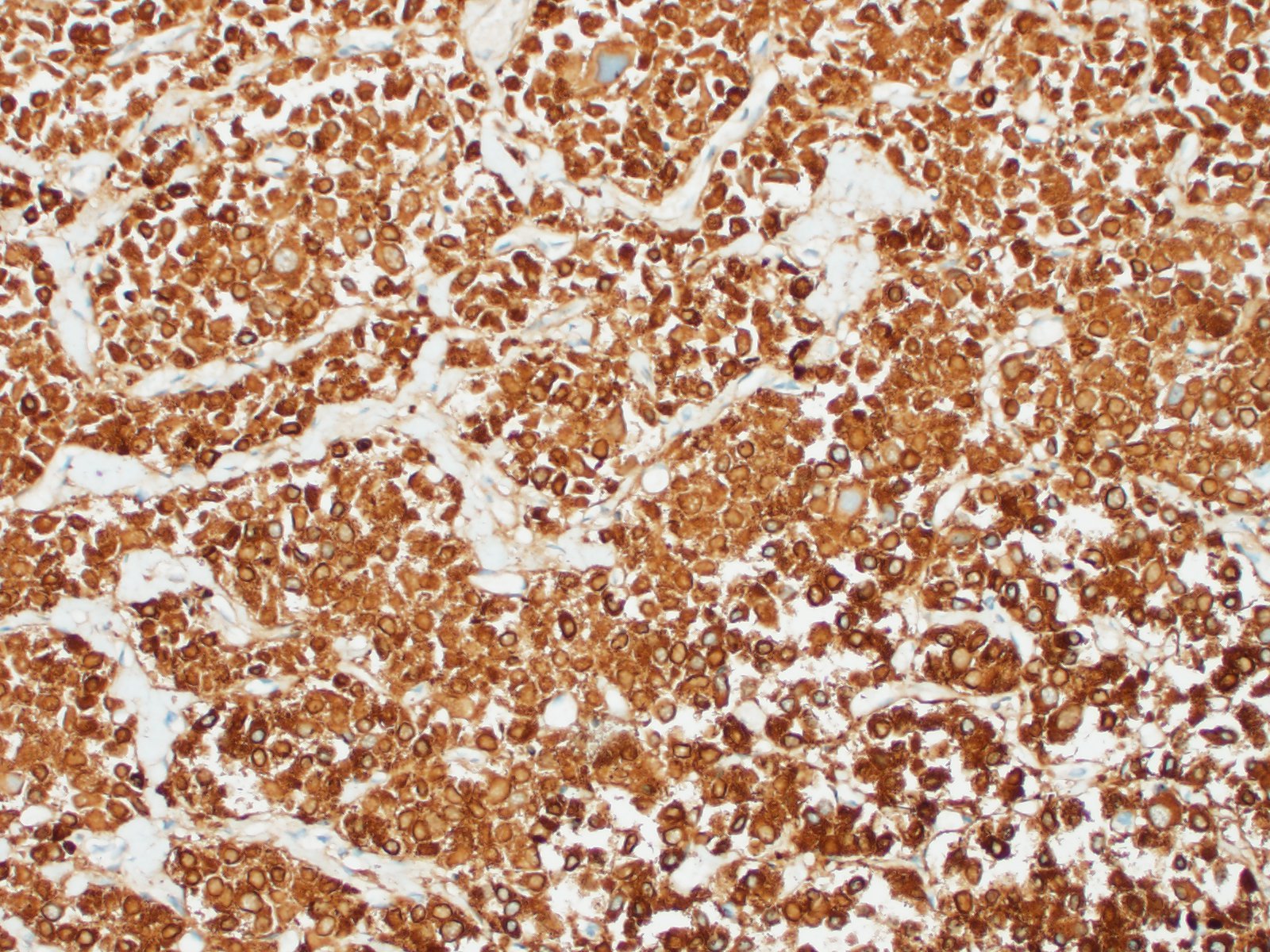

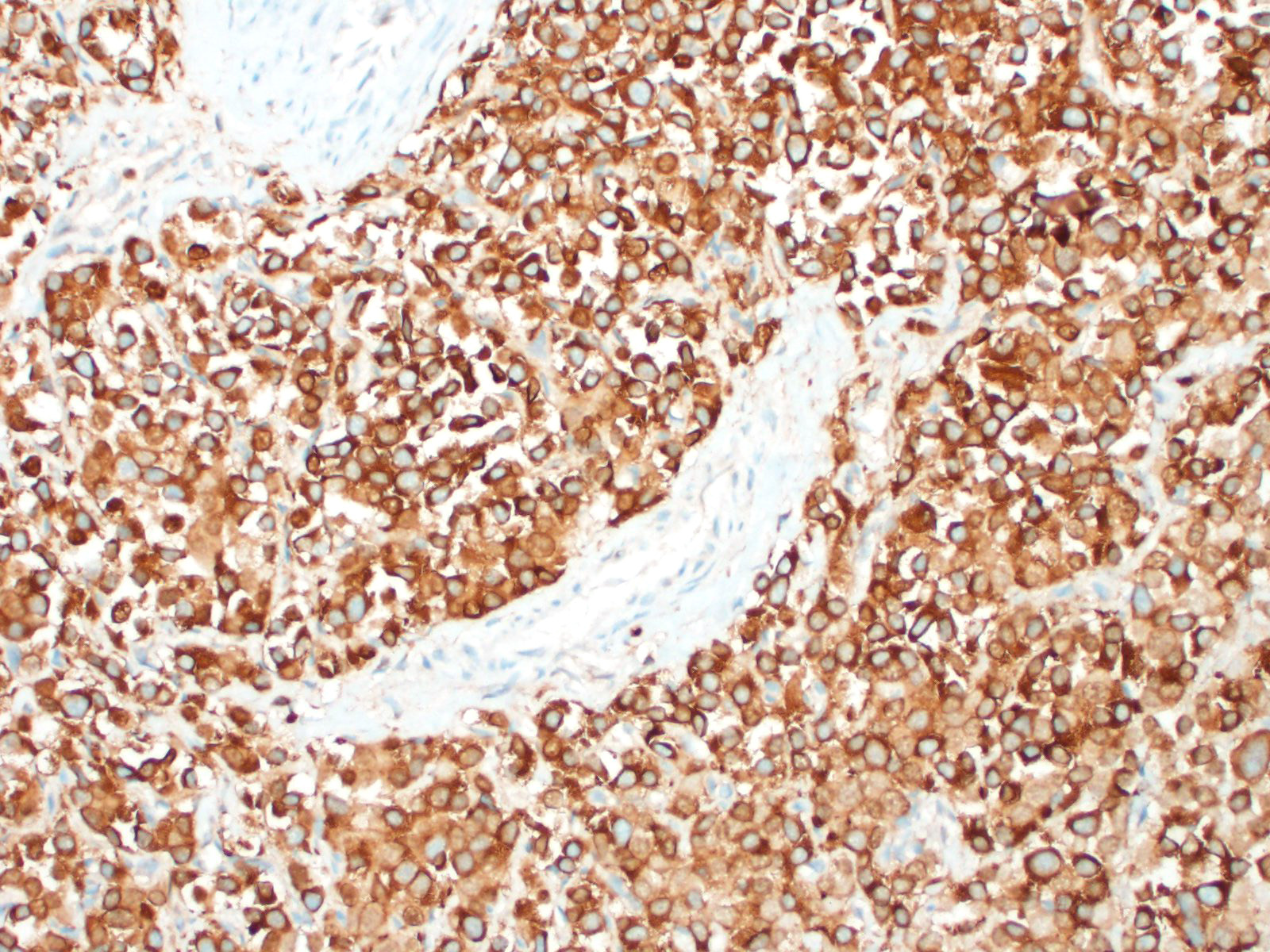

In general, paragangliomas are composed of tumor cells containing intracytoplasmic hormonal secretory granules which are revealed with an argyrophil reaction, such as Grimelius's methods. The neoplastic cells are typically arranged in nests or packets, known as a Zellballen pattern, and are surrounded by sustentacular cells.4,11,13,17,20 Giant neoplastic cells with bizarrely shaped, multilobed, densely basophilic nuclei are often seen.4,8 Immunohistochemically, they are positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin and neuron specific enolase (NSE). Ultrastructurally, both adrenalin- and noradrenalin-type granules are demonstrated in the cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells.3,11,13,22

In this case, the tumor developed within the right atrium, extended to the right atrial appendage, and left ventricular wall without involvement of the epicardial surface or the aortic body. Neoplastic cells exhibited the characteristic Zellballen pattern and stained positively for chromogranin A and synaptophysin. Although definitive testing was not performed to confirm the functionality of this tumor (urine catecholamine metabolite quantification for example) we suspect that this tumor was a functional sympathetic atrial paraganglioma based on location, histopathology, immunohistochemistry and classical catecholamine associated clinical signs (systemic hypertension and tachycardia); however, generalized cardiac dysfunction could account for the clinical signs of systemic hypertension and tachycardia.

In conclusion, we believe this is a great case to encourage the review of the classification and distribution of normal paraganglia as well as the appropriate name for neuroendocrine neoplasms arising within or near the heart base.

Contributing Institution:

University of Wisconsin

School of Veterinary Medicine

Madison, WI

https://www.vetmed.wisc.edu/departments/pathobiological-sciences/

JPC diagnosis:

Heart and great vessels: Paraganglioma (neuroendocrine carcinoma).

JPC comment:

The contributor provides a concise summary of these neoplasms. In human medicine, research has progressed to more advanced stages than in veterinary medicine, with the identification of approximately 40% of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas associated with germline pathogenic variants in 12 known susceptibility genes. Patients identified with the most increased risk have heterozygous pathogenic variations of SDHD, with primarily paternal transmission to offspring. This SDHD variation accounts for approximately 9% of all pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) complex is part of the mitochondrial respiratory pathway and plays a key role in the Kreb's cycle.6 In veterinary medicine, there has been loose association of chemodectoma and brachycephalic breeds of dogs. Proposed mechanisms have been related to oxygen tension,4 but a heritable trait unrelated to oxygen tension should not be discounted, as these breeds have been grossly manipulated over time.

Various treatments in canine patients with chemodectoma have been documented. While recent studies suffer from low statistical power, a study in six dogs with chemodectoma had measurable decrease in tumor volume following stereotactic body radiation, with a likely increased survival time.10 On the other hand, a retrospective study of dogs with chemodectoma and treated with toceranib (Palladia) showed no significant change in survival.9 While these early results will likely shape future treatment for this tumor type, caution should be exercised in extricating statistical meaning from these studies with small sample sizes.

During conference discussion, the moderator emphasized the importance of clinical history and gross pathology to help make the diagnosis in these cases. In this case, the neoplasm was likely functional, and was arising from the endocardial surface of the right atrium, making chemodectoma a less likely diagnosis.

References:

1. Aupperle H, Marz I, Ellenberger C, Buschatz S, Reischauer A and Schoon HA. Primary and secondary heart tumors in dogs and cats. J Comp Path. 2007;136:18-26. 876

2. Buchanan, J. W., Boggs, L. S., Dewan, S., Regan, J. and Myers N. C. Left atrial paraganglioma in a dog: echocardiography, surgery, and scintigraphy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 1998; 12: 109-115.

3. Brown PJ, Rema A, Gartner F. Immunohistochemical characteristics of canine aortic and carotid body tumors. J Vet Med. 2003;50:140.

4. Capen CC. Tumors of the endocrine glands. In: Meuten DL, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Ames, IA: lowa State Press; 2016: 828-833.

5. DuBray M.M, La Perle C, Jordan D. Endocrine System. In: M Piper. Dintzis T, Dintzis S.M. Comparative Anatomy and Histology: A Mouse and Human Atlas. 2012, Pages 211-227

6. Fishbein L. Pheochromocytoma/ Paraganglioma: Is this a Genetic Disorder? Current Cardiology Reports. 2019;21:104.

7. Fishbein L, Leshchiner I, Walter V, Pacak K, Nathanson K.L, Wilkerson M.D. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Cancer Cell. 2017; 31: 181-193.

8. Lam A.K. Update on Adrenal Tumors in 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) of Endocrine Tumors. Endocrine Pathology. 2017; 3: 213-227

9. Lew FH, McQuown B, Borrego J, Cunningham S, Burgess KE. Retrospective evaluation of canine heart base tumours treated with toceranib phosphate (Palladia): 2011-2018. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. 2019;17(4):465-471.

10. Magestro LM, Gieger TL, Nolan MW. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for heart-base tumors in six dogs. Journal of Veterinary Cardiology. 2018;20(3):186-197.

11. Moonim M.T. Tumours of chromaffin cell origin: phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Diagnostic Histopathology. 2012; 18: 234-244.

12. Rizzo SA, Newman SJ, Hecht S. Thomas WB. Malignant mediastinal extra-adrenal paraganglioma with spinal cord invasion in dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008; 20:372-375.

13. Romanucci M, Malatesta D. Cytological, histological and ultrastructural nuclear features of monster cells 151:57-62. in canine carotid body carcinoma. J Comp Path. 2014;

14. Robinson W.F, Robinson N.A. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2016:52-54.

15. Rosol T, Grone A. Endocrine glands. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2016:354-356.

16. Patnaik A.K, Erlandson R.A, Lieberman P.H. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma (paraganglioma) in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990; 197:104-106v

17. Stephanie M, Fliedner M.J, Brabant B, Lehnert H, Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: genotype versus anatomic location as determinants of tumor phenotype. Cell Tissue Res. 2018; 372:347-365.

18. Tischler, A. S. Pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma: updates. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2008; 132: 1272-1284.

19. Turley AJ, Hunter S, Stewart MJ. A cardiac paraganglioma presenting with atypical chest pain. Eur J of Cardio-Thoracic Surg, 2005. 28:352-354

20. Treggiari E, Pedro B, Dukes-Mc Ewan J, Gelzerand A.R, Blackwoo L. A descriptive review of cardiac tumors in dogs and cats. Veterinary and Comp. Onco. 2015; 15: 273-288.

21. Wey, A. C. and Moore, F. M. Right atrial chromaffin paraganglioma in a dog. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2012; 14: 459-464.

22. Yamamoto S, Fukushima R. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical evaluation of malignant potential in canine aortic body tumours. J Comp Path. 2013; 149:182-191.

23. Yanagawa H, Hatai H, Taoda T, Boonsriroj H, Kimitsuki K, Park C. Canine Case of Primary Intra-Right Atrial Paraganglioma. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2014 76(7): 1051-1053.