Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 5

25 August 2019

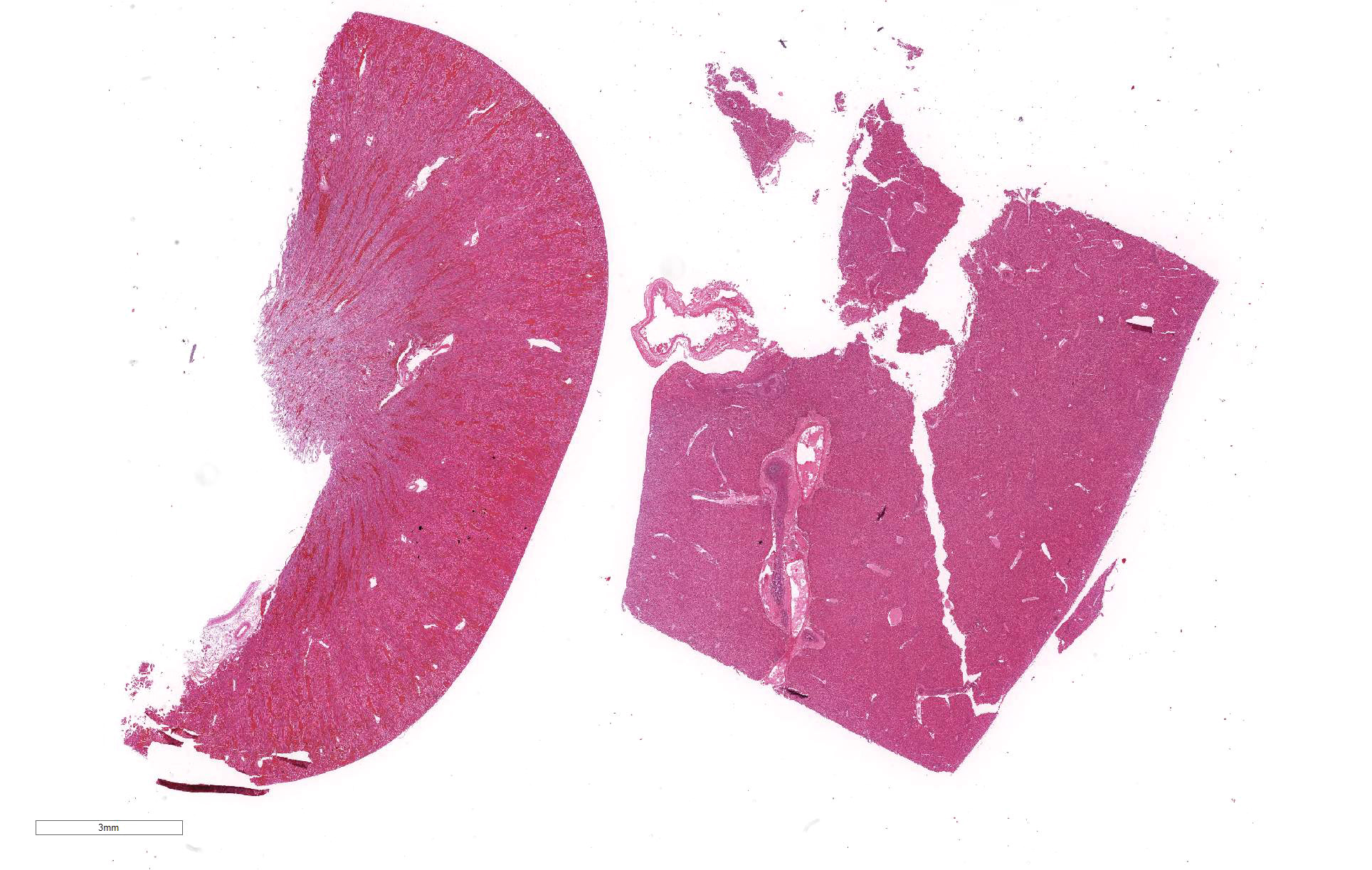

CASE III: Case 1 (JPC 4101226).

Signalment: 8-week-old female Rex cross rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus.

History: Found dead in the woods

Gross Pathology: The rabbit was one of several young rabbits housed and hand-reared at a rescue organization. Both this rabbit and its litter mate displayed symptoms of lethargy, anorexia and hypothermia. Within 48 hours of the onset of clinical signs, the rabbit died. The litter mate and several other young rabbits in the organization also died in the days following this death.

Laboratory results: Bacteriology : Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in liver and spleen.

Microscopic Description:

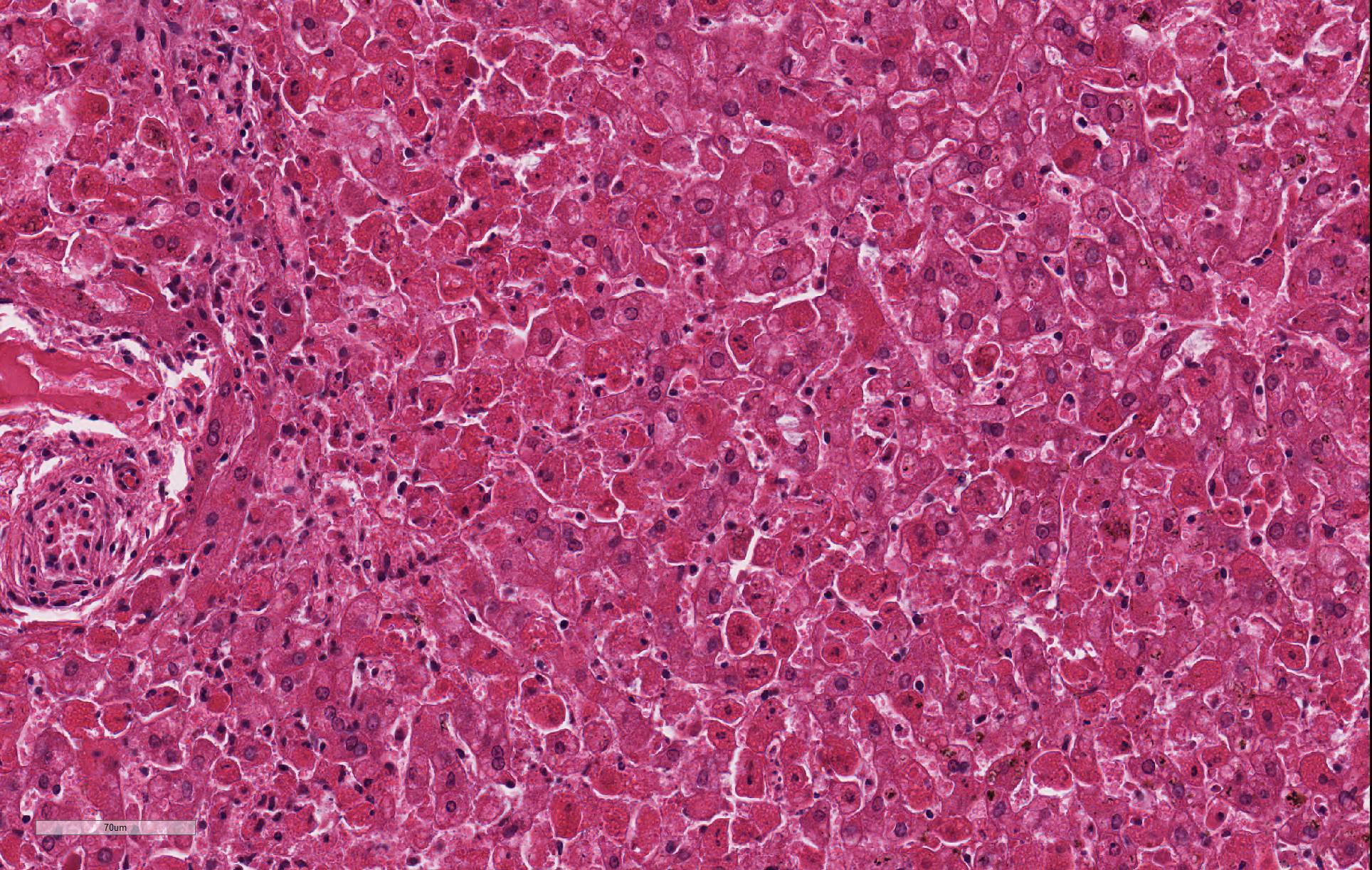

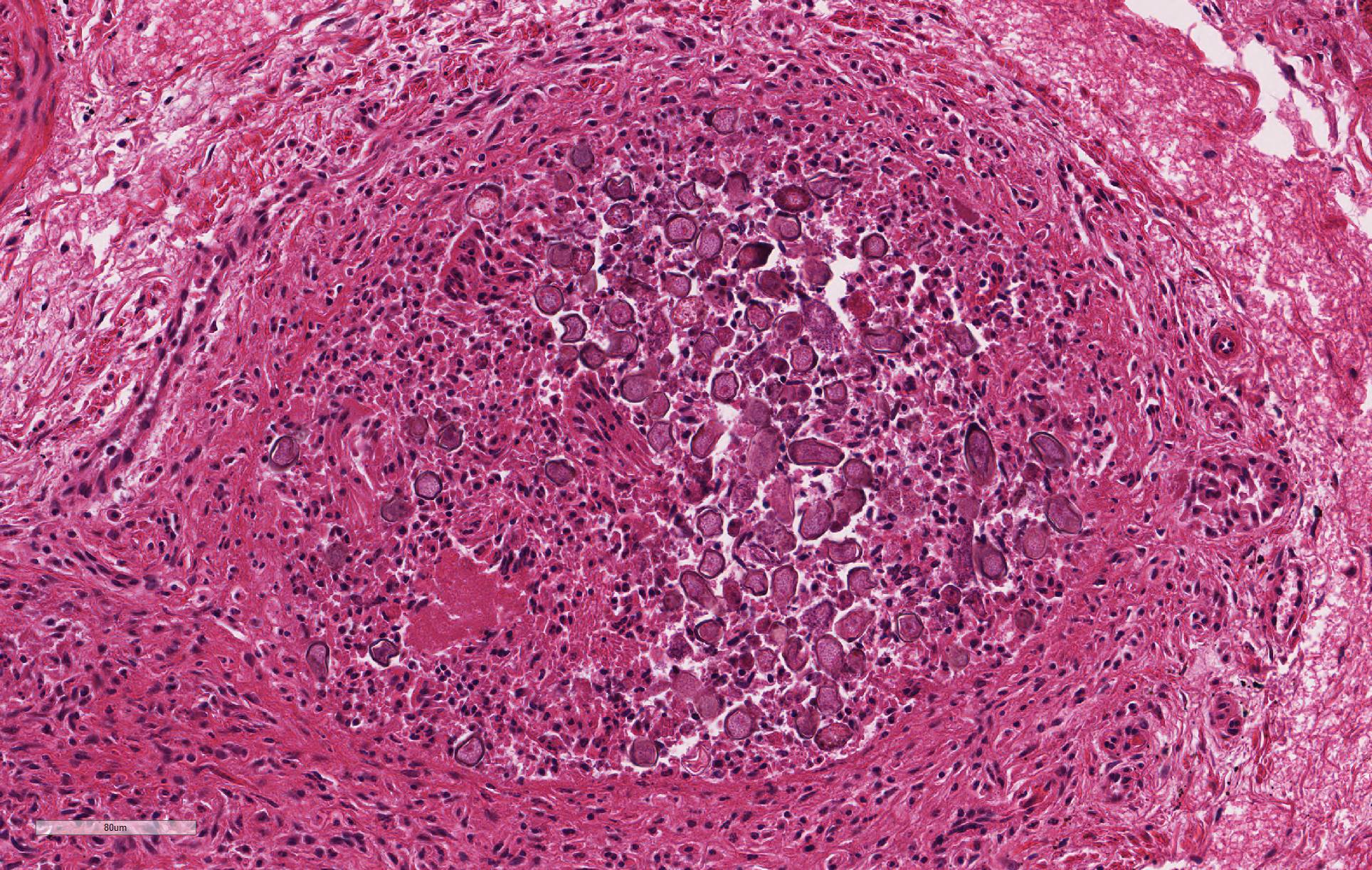

Despite moderate autolysis of the tissues, the liver has multifocal areas of hepatocytes with reasonable preservation. Scattered amongst these areas, and throughout the hepatic lobule, are swollen eosinophilic hepatocytes with varying degrees of pyknosis, karyolysis and karyorrhexis (necrosis) and marked loss of chord architecture. In addition to these findings, there is marked multifocal distention of bile ducts with periductal fibrosis expanding and compressing the surrounding hepatic parenchyma. The biliary epithelium is hyperplastic and forms papillary projections into the lumen. Numerous epithelial cells contain asexual and sexual developmental stages of coccidia and the biliary duct lumina contain large numbers of oocysts. Moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells and smaller numbers of heterophils are admixed within the periductal fibrous tissue and the connective tissue stroma of the papillary projections.

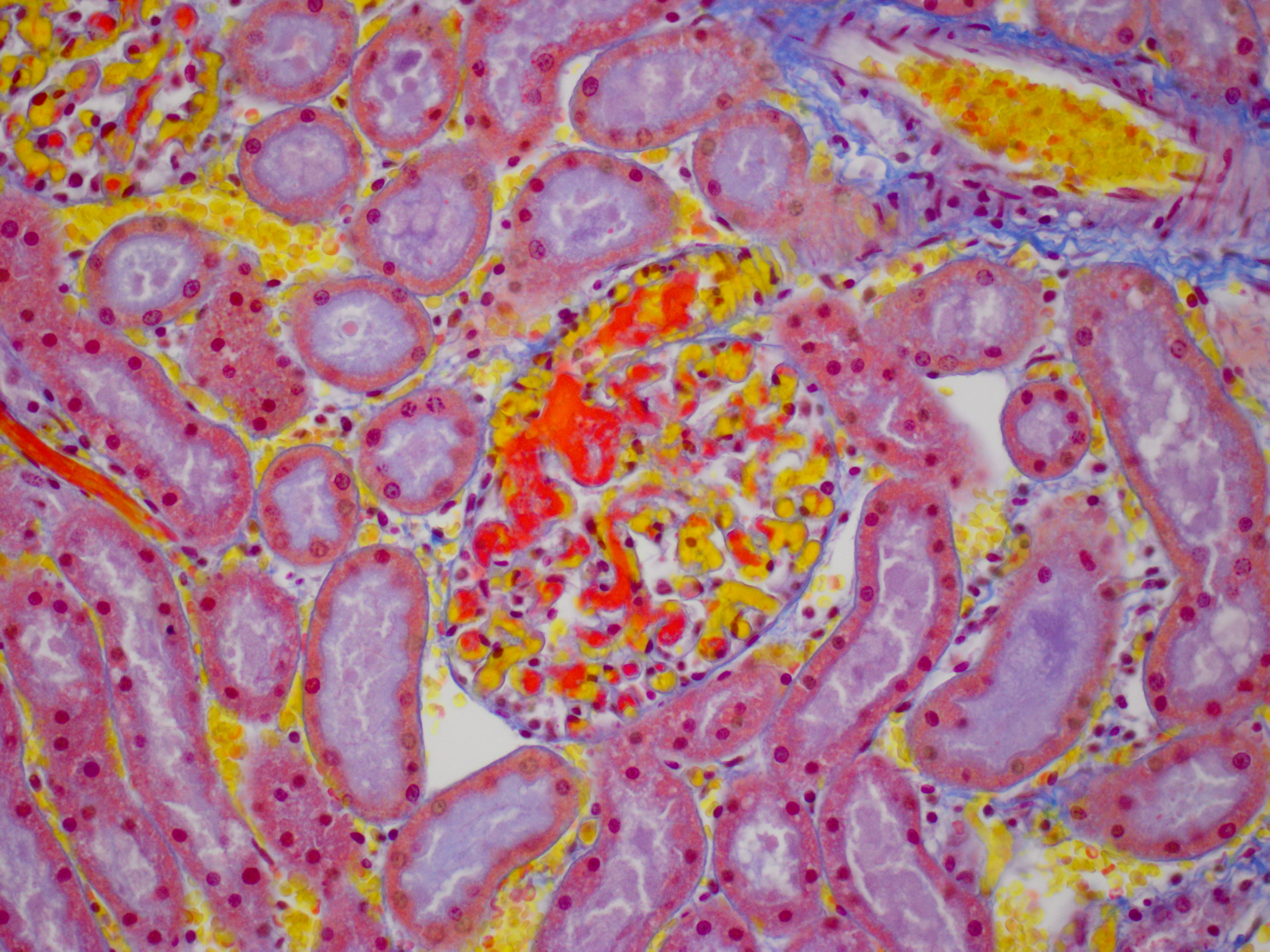

The kidney diffusely shows recent vascular congestion and tubular and glomerular hemorrhage. Intracapillary fibrin thrombi are present multifocally in glomeruli. Scattered renal tubular cells exhibit hypereosinophilic cytoplasm, pyknotic nuclei, karyorrhexis and karyolysis (necrosis).

Contributor Morphologic

Diagnoses:

Liver: Hepatitis, acute, moderate to severe, random with

hepatocellular necrosis

Liver: Cholangitis, proliferative, chronic severe with intraepithelial coccidia

Kidney: Nephritis, haemorrhagic, severe, acute, with multifocal glomerular thrombosis

Contributor Comment: In this case, the rabbit had two concurrent disease processes: hepatic coccidiosis (Eimeria stiedae) and rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD) caused by rabbit calicivirus. RHD was the cause of death, with hepatic coccidiosis as an incidental finding.

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease or viral hemorrhagic disease is caused by a calicivirus of the genus Lagovirus, which rapidly infects wild and domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculi). The virus was first identified in 1984 in China where it killed 140 million rabbits within months.21 It was released in Australia and New Zealand as a method of pest control of wild rabbits and is endemic in the populations in those countries.6,27

The RHD virus is highly infectious, with a greater than 80% mortality rate, and it usually produces death in affected individuals within 48 to 72 hours of infection.1,21 Death is due to acute liver damage and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).24 No clinical signs may be observed if the infection is peracute. Alternatively, they may manifest as anorexia, lethargy, pyrexia, conjunctival congestion and neurological signs such as ataxia, opisthotonos or paralysis in acute infections.13,29 Other signs such as dyspnea, cyanosis, or hemorrhagic epistaxis may also be seen. Subacute infections result in milder clinical signs, with some rabbits surviving. Many rabbits with chronic infections will die within 1 to 3 weeks after a period of jaundice, weight loss and lethargy.11

The primary findings at necropsy include hepatomegaly with an enhanced lobular pattern, splenomegaly, renomegaly, pulmonary hemorrhage and oedema, blood-tinged nasal discharge or bloody foam in the tracheal lumen.1,14 Additionally, hyperemia or sub-serosal hemorrhages may be found on multiple organs such as the intestine, pericardium, kidney and lungs.1

The primary histopathological lesion is an acute necrotizing hepatitis.2 In adult rabbits, the virus has tropism for hepatocytes and can be detected in the liver a few hours post-infection.2 Viral replication occurs primarily in hepatocytes in the centrilobular areas but also in Kupffer cells.2,8-10,22 Additionally, viral antigen has been detected in macrophages of the spleen, alveoli, kidneys and small intestine.22,23 The virus induces apoptosis in these cells, releasing viral progeny to infect other cells.7 In younger rabbits, viral antigen has been detected only in rabbits greater than 4 weeks of age.18,22 Younger rabbits appear to be resistant to the RHD virus. Rabbits less than 3 weeks of age are fully resistant, and this resistance decreases as rabbits increase in age to 8 weeks old, where mortality rates are the same as adult rabbits.1

The mechanism of resistance is unclear. It is thought to relate to viral attachment to the carbohydrate group of host-cell histo-blood group antigens (HBGA).24,25 RHD attaches to HBGA H type 2, A type 2 and B type 2 oligosaccharides which are found on the surface of epithelial cells of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts. The expression of HBGA H type 2 seems to be mostly lacking in the upper respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts of resistant rabbits.17 However, other factors must be involved in viral attachment to cells as hepatocytes, which are the main cell involved in viral replication, do not contain these HBGA receptors.25 Additionally, in young rabbits, viral replication occurs only in a small fraction of hepatocytes, indicating other factors are involved in the resistance to this virus.1

In this rabbit, hepatic coccidiosis, was an incidental finding that likely contributed to its poor condition. Eimeria stiedae is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in rabbits. Ten other species of Eimeria spp. infect the domestic rabbits but specifically infect the gastrointestinal tract.15,17 Clinical signs for hepatic coccidiosis include a thin body condition, diarrhoea, a pot-bellied appearance and, in severe cases, icterus.21

Young, weanling rabbits are most often infected when ingestion of the sporulated oocyst from the environment occurs. The oocysts are shed after a prepatent period of 15 to 18 days, and once in the environment, are extremely resistant to disinfectants.21

Sporulated oocysts are ingested, where sporozoites are released to invade the duodenal mucosa and lamina propria.18 It is possible that sporozoites are then transported to the liver via either lymphatic or hematogenous spread. Organisms have been found in macrophages in the lymphatics and in regional lymph nodes within 12 hours of exposure, in bone marrow within 24 hours and in the liver within 48 hours.18,21 Once in the liver, sporozoites invade the epithelial cells of bile ducts to become trophozoites. Trophozoites undergo the asexual division of schizogony and merogony over several generations to eventually form the macro- and microgametocytes involved in sexual division. Fertilization of a macrogametocyte by a microgametocyte to form an oocyst which is then shed in the feces.18,21

Contributing Institution:

Institute of Veterinary Animal and Biomedical Sciences, Massey University

Private Bag 11222, Palmerston North

New Zealand 4442

JPC Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing (it’s really

apoptosis), diffuse, severe.

2. Liver, bile ducts: Epithelial hyperplasia, diffuse, mild to moderate, with intraluminal apicomplexan oocysts.

JPC Comment: The

contributor has done an excellent review of a virus of global import in this

species, as well as well-known common parasite of young rabbits.

The Czech v351 strain of rabbit lagovirus has been used in Australia and New

Zealand (following illegal release on the South island) to control pest

rabbits for a number of years.14 However,

even before this virus was released into a naive population, wild rabbits demonstrated

cross-reacting antibodies suggesting other similar viruses had previously

circulated within this population. The first non-pathogenic rabbit calicivirus

was identified in Italy, following seroconversion of animals in a rabbitry with

no history of clinical disease. Shortly thereafter, a non-pathogenic strain of

rabbit calicivirus with 88% was identified in Australia, and New Zealand. One

common factor was that these viruses appeared to prevail in cool high-rainfall

areas.14 Additional "benign"

viruses have also been identified in European hares in Australia, with evidence

of previous recombination, confirming previous hypotheses of the origin of

genetic diversity within this genus of virus.12 In 2014, a

recombinant strain of RHDV was identified in Australia which contained capsid

and non-structural genes of non-pathogenic RHDV variants.12

Other interesting changes have been noted in RHDV since its release thirty years ago in Australia. In contrast to myxoma virus, which was also released into the wild to control pest rabbits and rapidly attenuated in virulence over time as local rabbits developed genetic resistance, pathogenic genotypes of Australian RHDV appear to have increased in virulence.7 A comparison study of deaths in a closed population experiencing outbreaks back to the original release of RHDV noted that in outbreaks from 2007-2009 (as compared to the 1990’s), more recent outbreaks demonstrated elevation in case fatality rates, disease duration (time to death), as well as the amount of virus produced in infected animals.7

The first lagovirus other than RHVD infecting rabbits in the United States was

identified by Bergin et al in 2009. This virus, referred to as Michigan rabbit

calicivirus occurred in a closed rabbitry with an approximately 32% case

mortality and clinical and necropsy findings of epistaxis, vulvar hemorrhage,

diarrhea, and ocular discharge. This virus averaged 79% homology with the RNA

genome of RHDV virus. The rabbitry was ultimately depopulated.5

References:

1. Abrantes J, van der Loo W, Le-Pendu J, Esteves PJ. Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV): a review. Veterinary research 2012; 43: 12.

2. Alonso C, Oviedo JM, Martin-Alonso JM, Diaz E, Boga JA, Parra F: Programmed cell death in the pathogenesis of rabbit hemorrhagic disease. Arch Virol 1998;143: 321-332.

3. Barriga OO, Arnoni JV. Eimeria stiedae: weight, oocyst output and hepatic function of rabbits with graded infections. Experimental Parasitology 1979; 48:407-414.

4. Barriga OO, Arnoni JV. Pathophysiology of hepatic coccidiosis in rabbits. Veterinary Parasitology 1981; 8:201-210.

5. Bergin IL, Wise AG, Bolin SR, Mullaney TP, Kiupel M, Maes. RK. Novel calicivirus identified in rabbits, Michigan, USA. Emerg Infec Dis 2009; 15(12)1955-1962.

6. Cooke BD. Rabbit haemorrhagic disease: field epidemiology and the management of wild rabbit populations. Rev Sci Tech 2002; 21:347-358.

7. Elsworth P, Cooke BD, Kovaliski J, Sinclair R, Holmes EC, Strive T. Increased virulence of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus associated with genetic resitance in wild Australia rabbits. Virology 2014; 10:415-423.

8. Gelmetti D, Grieco V, Rossi C, Capucci L, Lavazza A. Detection of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) by in situ hybridisation with a digoxigenin labelled RNA probe. J Virol Methods 1998; 72:219-226.

9. Jung JY, Lee BJ, Tai JH, Park JH, Lee YS: Apoptosis in rabbit haemorrhagic disease. J Comp Pathol 2000; 123:135-140

10. Kimura T, Mitsui I, Okada Y, et al. Distribution of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus RNA in experimentally infected rabbits. J Comp Pathol 2001; 124:134-141.

11. Lavazza A, Capucci L. How Many Caliciviruses are there in Rabbits? A Review on RHDV and Correlated Viruses In: Alves PC, Ferrand N, Hackländer K, eds. Lagomorph Biology. 1st ed. Berlin, Germany: Springer 2008:263-278.

12. Mahar JE, Hall RN Shi M, Mourant R, Hung N, Strive T, Holmes EC. The discovery of three new hare lagoviruses reveals unexplored viral diversity in this genus. Virus Evol 2019; 5(1): vewz005.

13. Marcato PS, Benazzi C, Vecchi G, et al. Clinical and pathological features of viral haemorrhagic disease of rabbits and the European brown hare syndrome. Rev Sci Tech 1991; 10: 371-392.

14. Mitro S, Krauss H. Rabbit hemorrhagic disease: a review with special reference to its epizootiology. Eur J Epidemiol 1993; 9:70-78.

15. Moussa A, Chasey D, Lavazza A et al. Haemorrhagic disease of lagomorphs: evidence for a calicivirus. Vet Microbiol 1992; 33: 375-381.

16. Nicholson LJ, Mahar JE, Strive T, Zheng T, Holmes EC, Ward VK, Duckworth JA. Benign rabbit calicivirus in New Zealand. Applied Env Microbiol 2017; e00090-17

17. Nyström K, Le Gall-Reculé G, Grassi P et al. Histo-blood group antigens act as attachment factors of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus infection in a virus strain-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog 2011; 7:1-22.

18. Owen D. Life cycle of Eimeria stiedae. Nature 1970; 227:304.

19. Pakandl M. Coccidia of rabbit: a review. Folia Parasitologica 2009; 56(3):153-166.

20. Park JH, Lee YS, Itakura C. Pathogenesis of acute necrotic hepatitis in rabbit hemorrhagic disease. Lab Anim Sci 1995; 45:445-449.

21. Percy DH, Barthold SW, Griffey SM. Rabbit In: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 4th ed. Ames, Iowa, USA: Blackwell Publishing; 2016: 253-323.

22. Prieto JM, Fernandez F, Alvarez V et al. Immunohistochemical localisation of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus VP-60 antigen in early infection of young and adult rabbits. Res Vet Sci 2000; 68:181-187.

23. Ramiro-Ibáñez F, MartÃn-Alonso JM, GarcÃa Palencia P, Parra F, Alonso C. Macrophage tropism of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus is associated with vascular pathology. Virus Res 1999; 60:21-28.

24. Ruvoen-Clouet N, Blanchard D, Andre-Fontaine G, Ganiere JP. Partial characterization of the human erythrocyte receptor for rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus. Res Virol 1995, 146:33-41.

25. Ruvoen-Clouet N, Ganiere JP, Andre-Fontaine G, Blanchard D, Le Pendu J. Binding of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus to antigens of the ABH histo-blood group family. J Virol 2000; 74:11950-11954.

26. Shien JH, Shieh HK, Lee LH. Experimental infections of rabbits with rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus monitored by polymerase chain reaction. Res Vet Sci 2000; 68:255-259.

27. Thompson J, Clark G. Rabbit calicivirus disease now established in New Zealand. Surveillance 1997; 24:5-6.

28. Ueda K, Park JH, Ochiai K, Itakura C. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in rabbit haemorrhagic disease. Jpn J Vet Res 1992; 40:133-141.

29. Xu ZJ, Chen WX: Viral haemorrhagic disease in rabbits: a review. Vet Res Commun 1989; 13: 205-212.

1.