Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 16

16 January, 2019

CASE IIV: UW-SVM Case 2 (JPC 4018823).

Signalment: 1-year-old, intact male, Boxer, canine (Canis lupus familiaris)

History: This dog was under treatment for 4 months for waxing and waning episodes of pyrexia, cervical pain and ataxia (cerebellar and proprioceptive), which progressed to a non-ambulatory state. In addition, valvular endocarditis was diagnosed 2 months following the initial presentation, based on a 2/6 cardiac murmur and an echocardiogram which showed a vegetative lesion on the aortic valve. Complete blood count showed a neutrophilic leukocytosis. Treatment included non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and various antibiotics (amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid, sulfadimethoxine, cephalexin, ciprofloxacin) for suspected bacterial endocarditis. When negative test results were obtained for a variety of infectious diseases (see laboratory results), a presumptive diagnosis of immune-mediated meningoencephalomyelitis was made and the dog was placed on an immunosuppressive dose of prednisone; antibiotic treatment was continued. There was clinical improvement which then mildly regressed. Azathioprine was added to the immunosuppressive protocol; dramatic clinical improvement ensued which lasted approximately 6 weeks. The dog then showed signs of profound lethargy, weakness, a return of ataxia and mild cervical pain, dyspnea, tachycardia, and pale mucus membranes. The cardiac murmur had resolved. Further testing and treatment were declined and the dog was euthanized.

Gross Pathology: The dog was in poor body condition with marked skeletal muscle wasting and scant adipose stores. The liver was diffusely tan, variably friable to mildly firm, and enlarged (4.8% body weight). The lungs were diffusely rubbery, wet, and heavy, and oozed abundant serosanguinous fluid on section; the parenchyma contained four poorly demarcated tan to grey semi-firm nodules ranging from 0.7 cm to 2.5 cm in widest dimension. The trachea contained pink foam and dark red, cloudy watery fluid from the larynx to the carina. The sternal and tracheobronchial lymph nodes were moderately enlarged. The pancreas was pink mottled tan and adjacent fat and omental fat had multifocal firm yellow foci (pancreatitis with fat necrosis). Adrenal cortices were bilaterally thin. There were few small raised crusted foci on metatarsal and metacarpal skin. Cardiac valves were grossly normal, indicating resolution of previous valvular endocarditis.

Laboratory results:

Antemortem results:

Complete blood count: Neutrophilic leukocytosis at initial presentation. Mild anemia and mild neutrophilia 1 week prior to euthanasia. Blood culture, urine culture: no growth. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis: increased protein, neutrophilic pleocytosis, no organisms seen. Blastomyces EIA negative. Neospora caninum IFA negative. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever titer negative. Lyme C6 4DX SNAP: negative for Ehrlichia canis, Dirofilaria immitis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum.

Postmortem results:

Cytology on lung nodules, impression smear: The sample contained many oval to crescentic protozoal organisms, approximately 2x6 microns, with a 1-2 micron diameter basophilic nucleus, along with many macrophages, fewer degenerate neutrophils, and a heavy background of erythrocytes.

CSF cytology: The sample contained many neutrophils and macrophages; no organisms were seen.

PCR on lung tissue for Toxoplasma gondii: positive (Ct=16.92). Neospora caninum PCR negative.

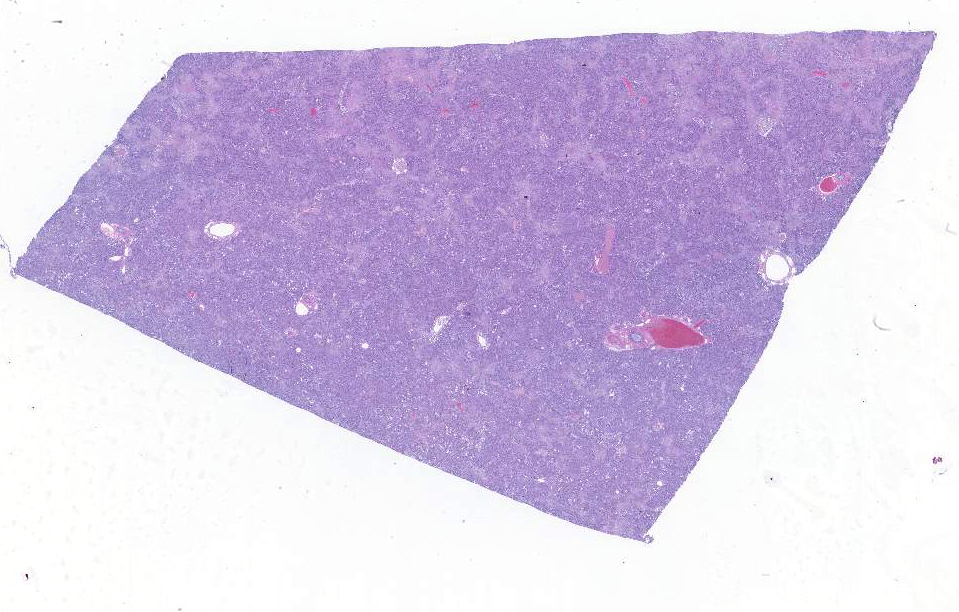

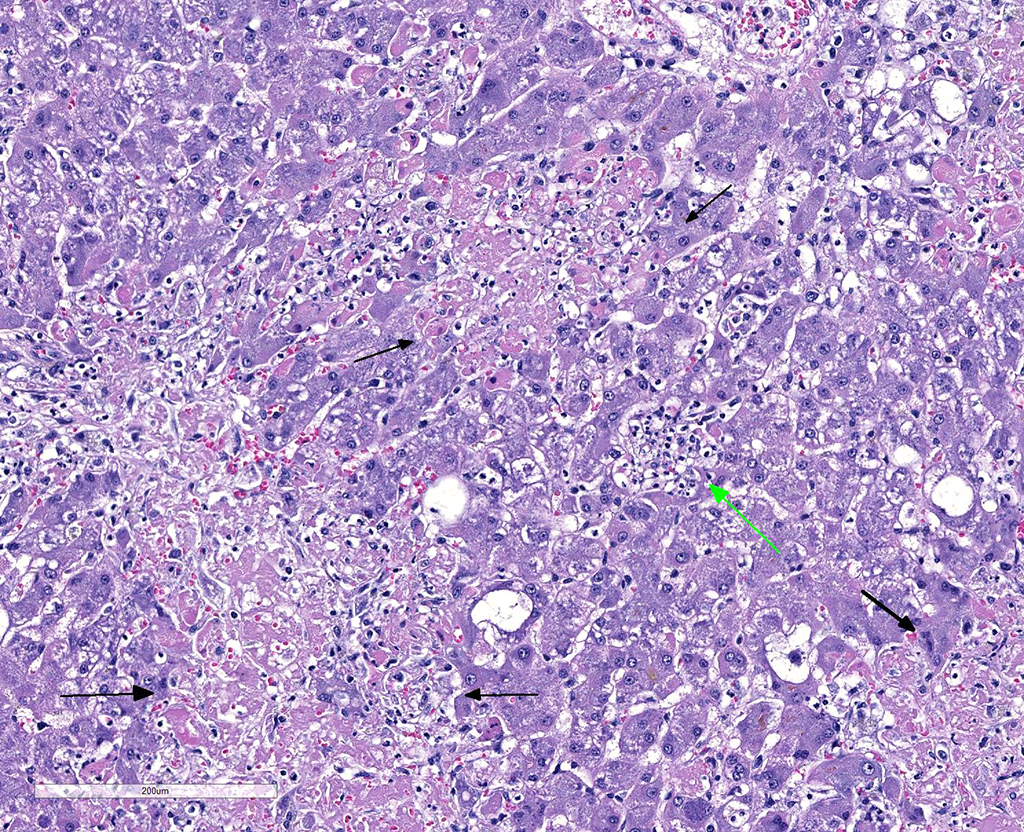

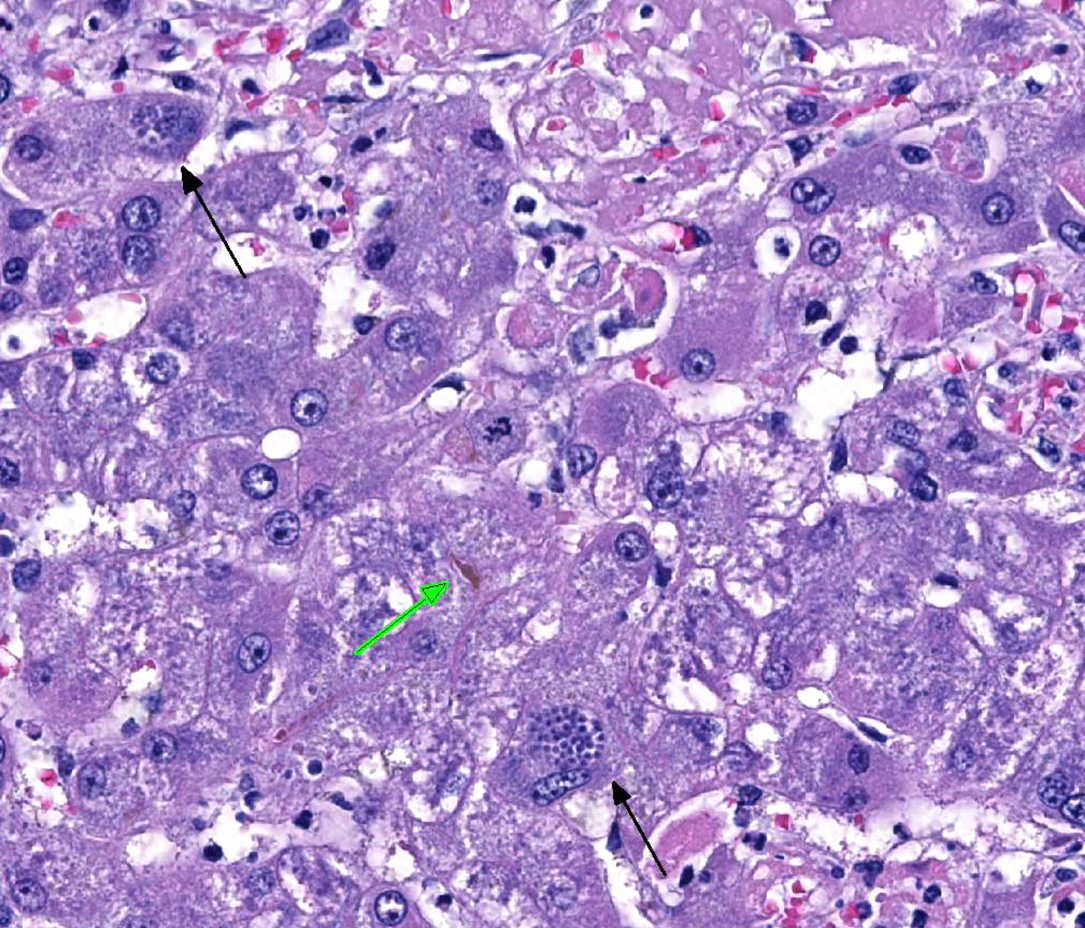

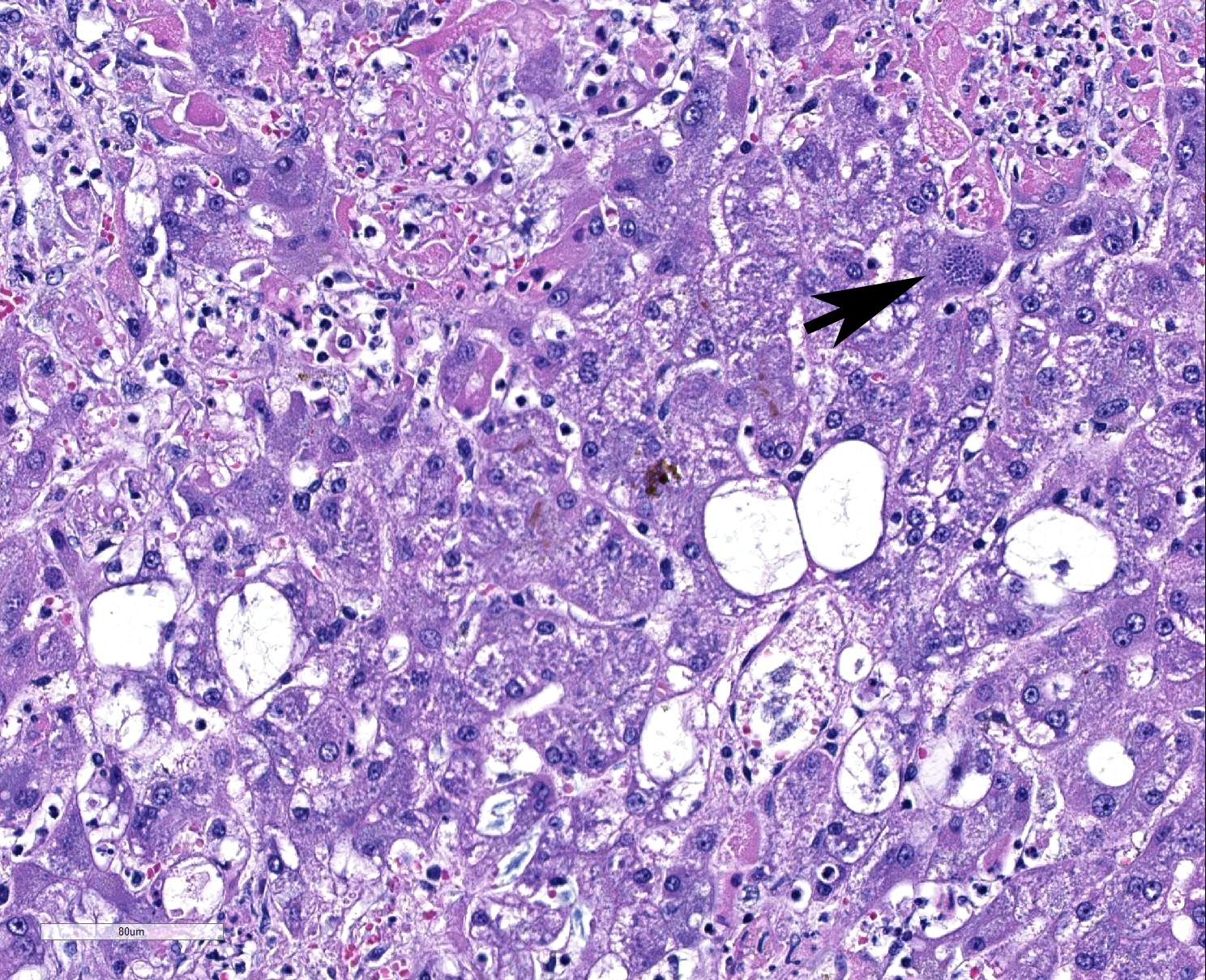

Microscopic Description:

Liver: Multifocally throughout the liver are many random, occasionally coalescing foci of hepatocellular necrosis, in total affecting up to ~1/3-1/2 of the parenchyma. Hepatocellular necrosis is characterized by one or more of the following: pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with loss of cellular detail and retention of cellular outlines (coagulation necrosis), fragmentation of cytoplasm, karyolysis or karyorrhexis, and replacement of cells by cellular and karyorrhectic debris, fibrin, and few to moderate numbers of neutrophils with fewer macrophages and erythrocytes. Within few hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and macrophages are small clusters or variable numbers of individual 2-4 micron, round to oval protozoal organisms with a small round basophilic nucleus. Most remaining hepatocytes are mildly to moderately swollen and contain irregular, variably sized cytoplasmic clearings (glycogen-type vacuolar change), with few small random foci and individual cells showing severe swelling and vacuolar degeneration. Multifocally few bile canaliculi are dilated by green-orange bile. Few portal areas are mildly expanded by immature fibrous connective tissue which occasionally extends along surrounding sinusoids; these areas are often bordered by a focus of necrosis.

Additional histologic findings: Multiple other organs also had necrosis with protozoa, including the lung, pancreas, and myocardium, and accompanied by varying amounts of inflammation. The central nervous system had minimal to mild multifocal non-suppurative meningoencephalomyelitis with microglial nodules and few protozoal cysts that were usually not associated with areas of inflammation. Skeletal muscle had mild myonecrosis with protozoal cysts in few viable myocytes. A focal necrosuppurative skin lesion on the metatarsus contained angioinvasive pigmented fungal hyphae (phaeohyphomycosis). There was bilateral adrenocortical atrophy.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Liver:

- Multifocal to coalescing random hepatocellular necrosis with protozoal organism

- Moderate to marked diffuse hepatocellular vacuolar degeneration, glycogen-type (steroid-induced hepatopathy)

- Mild multifocal portal fibrosis; mild extracellular cholestasis

Contributor’s Comment: Toxoplasma gondii is a coccidian protozoal parasite found worldwide that can cause systemic infection in the definitive hosts (members of the Felidae) as well as intermediate hosts (other warm-blooded animals, including humans), though subclinical infections are more common.3,6

The life cycle includes an asexual and sexual enteroepithelial cycle that occurs only in felids, and a tissue cycle that occurs in felids and intermediate hosts.3,6 The host becomes infected by ingesting the organism in the form of sporulated oocysts in cat feces or in material contaminated by cat feces, or in the form of tachyzoites or encysted bradyzoites in tissues of intermediate hosts.3,4 Vertical transmission can also occur. Tachyzoites replicate in a wide variety of host cells, and spread throughout the body from the intestine via lymphatics or the portal system, within leukocytes or free in plasma.3 Intracellular replication of tachyzoites causes focal necrosis, which may be followed by inflammation. Tissue cysts containing bradyzoites tend to form in brain and skeletal muscle; immunocompromise may cause these latent tissue cysts to release the zoites and reinitiate systemic infection.3

Systemic infection occurs most often in young animals and immunocompromised animals, and in dogs can accompany diseases such as canine distemper, lymphoma, or ehrlichiosis.3 It has also been reported in dogs undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.3,6

Lesions of toxoplasmosis are typically necrosis followed by inflammation, and organs most often affected include the lungs and central nervous system; neurologic and respiratory signs are most common and can be confounding in cases of dual infection with canine distemper.3 Pulmonary lesions include necrosis of the alveolar septa and interstitial pneumonia. Central nervous system lesions include multifocal necrosis and non-suppurative inflammation, with microglial nodules forming in more chronic cases, but as rapidly as 1-2 weeks following infection. Cysts can form in chronic cases as the infection becomes quiescent.

Hepatocellular glycogen-type vacuolar degeneration (hepatic glycogenosis, glucocortocoid hepatopathy) is due to excess exogenous or endogenous corticosteroids.5 In this case, an immunosuppressive dose of prednisone caused steroid-induced hepatopathy as well as adrenocortical atrophy. Focal necrotizing dermatitis due to phaeohyphomycosis was presumably an opportunistic infection in this immunocompromised dog.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathobiological Sciences

School of Veterinary Medicine

University of Wisconsin–Madison

JPC Diagnosis:

- Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, random, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, with edema and intrahepatocytic, intrahistiocytic, and extracellular apicomplexan zoites.

- Liver, hepatocytes: Glycogenosis, multifocal, moderate.

JPC Comment: The contributor has presented an excellent review of the systemic infection associated with T. gondii. Within the 15 years, much has been learned about the T. gondii infection at the cellular level as well including mechanisms of invasion, replication, and egress, as well as the body’s mechanisms to control T. gondii and mechanisms that it has evolved to escape those mechanisms.2

Interestingly, the parasite forms found intracellularly and extracellularly represent distinct biological states. Extracellular parasites are motile, non-replicative, and designed to extrude the conoid and secrete the contents of their microneme organelles. Intracellular parasites divide, are non-motile and do not secrete micronemes or extrude their conoid. Marked changes in gene expression, mRNA production and translation, and changes in glycolytic pathways of energy production are required from the transition between the two stages.2

IFNγ appears to be the lynchpin of mammalian resistance to T. gondii infection.2 IFNγ upregulates a variety of anti-parasite genes whose expression kills the parasite by a number of mechanisms. These include autophagy-dependent degradation of the parasitophorous vacuolar membrane by the p47 family of IFNγ-regulated GTPases (IRGs) as well as the degradation of essential nutrients such as tryptophan by indoleamine dioxygenase. Toxoplasma has developed two primary ways of evading these IFNγ-mediated effects. Toxoplasma has evolved the ability to produce and secrete proteins which directly inactivate IFNγ-stimulated mediators, including the aforementioned GTPases (effective in most species except higher primates, which do not apparently produce them. Moreover, it can also directly interfere with IFNγ-regulated gene expression, by blocking the binding of STAT1 transcription factors from binding to their target genes.2

A number of other cases of toxoplasmosis have been included in the WSC within the last ten years: dog (Liver; WSC 2014 Conf 10 Case 1), cat (Duodenum, WSC 2009-2010, Conference 16 Case 2), and mole (Liver, WSC 2016 Conf 11, Case 4).

References:

- Bernsteen L, Gregory CR, Aronson LR, Lirtzman RA, Brummer DG: Acute toxoplasmosis following renal transplantation in three cats and a dog. JAVMA 1999; 15:1123-1126,

- Blader I, Coleman B, Chen C, Gubbles M. The lytic cycle of Toxoplasma gondii: 15 years later. Annu Rev Microbiol 2015; 69:463-485.

- Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK: Alimentary system. In: Jubb Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol 2, pp. 270-273. Elsevier Limited, Philadelphia, PA, 2007.

- Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP: Apicomplexa: Toxoplasma and Hammondia. In: An atlas of protozoan parasites in animal tissues, 2nd ed., pp. 53-56, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC, 1998.

- Stalker MJ, Hayes MA: Liver and biliary system. In: Jubb Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol 2, pp.309-310. Elsevier Limited, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

- Webb JA, Keller SL, Southorn EP, Armstrong J, Allen DG, Peregrine AS, Dubey JP: Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated toxoplasmosis in an immunosuppressed dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 41:198-202, 2005