Signalment:

Gross Description:

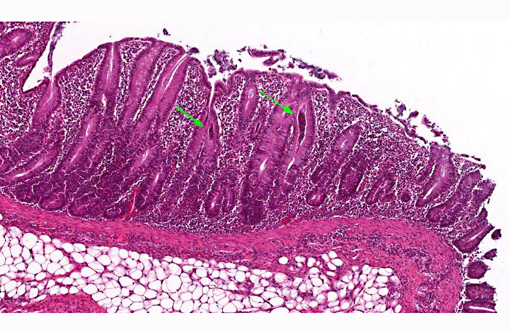

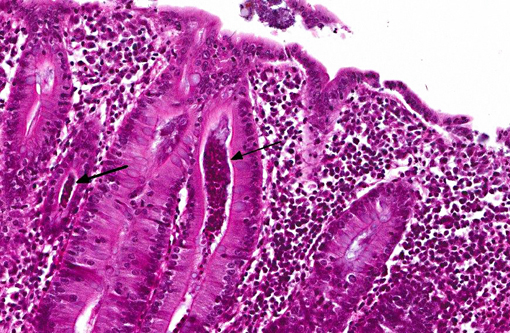

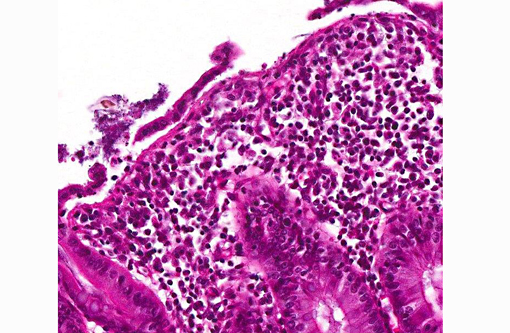

Histopathologic Description:

In the deeper parts of some crypts (moderate numbers in the colon of pig 13/226, and few in the cecum from pig 13/226 and colon from pig 13/227) there were luminal pyriform to crescent-shaped organisms, approximately 5 x 7 μm in size, with a faint nucleus and eosinophilic cytoplasm (consistent with trichomonads).Â

In a few sections there were also a few ciliated large protozoa (Balantidium coli) on the surface of the mucosa (incidental finding).Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The protozoal organisms located in colonic crypts were interpreted as trichomonads. Tritrichomonas suis is considered to be an apathogenic commensal in pigs that may colonize nasal cavity and intestines of pigs. This species has been found to be identical in sequence to T. foetus,(2,7) a venereally transmitted pathogen that affects cattle; however, other trichomonads may also be identified in fecal samples from pigs, such as Tetratrichomonas buttreyi,(6) Trichomitus rotunda and others unrelated to previously described trichomonads.(5)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

C. perfringens type C is associated with outbreaks of necrohemorrhagic enteritis in suckling piglets, while C. difficile is recognized as a cause of fibrinous typhlocolitis and mesocolonic edema in neonatal piglets see ( WSC 2013-2014, conference 17, case 1 for a more detailed discussion of Clostridium spp.). Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) causes profuse watery diarrhea in neonatal piglets via heat-labile (LTI and LTII) and heat-stable (STa and STb) enterotoxins (see WSC 2013-2014, conference 12, case 2 for a more detailed discussion of E. coli); however, histological changes are typically minimal. Enteropathogenic (attaching and effacing) E. coli is a less frequently reported cause of diarrhea in swine, and, although an uncommon manifestation, enteritis has also been associated with some strains of enterohemorrhagic, Shiga-like toxin producing E. coli, the cause of porcine edema disease. The whipworm Trichuris suis inhabits the cecum and colon of swine, where it embeds in the surface epithelium; severe infections may lead to mucohemorrhagic typhlocolitis.(1)

There are two coronaviruses associated with porcine diarrhea. Transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) is a highly contagious disease that is most severe in piglets younger than 10 days of age, characterized by high morbidity with vomiting and profuse diarrhea. The causative agent, a group 1 porcine coronavirus, destroys intestinal villar epithelial cells, resulting in marked villar atrophy and diarrhea secondary to malabsorption. Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) virus is another group 1 coronavirus that causes similar, though less severe signs in older pigs. The PED virus is endemic in many Asian countries, and has been present in Europe since the early 1970s; however, until recently (i.e., May 2013), it was not present in the United States, and its emergence has caused epidemic disease with important economic implications for the American pork industry. Rotavirus is enzootic in many swine herds and causes villar atrophy with ensuing diarrhea in both suckling and weaned pigs, although it is generally less severe than TGE. Finally, porcine adenoviral inclusions have been identified within small intestinal enterocytes in both asymptomatic pigs and those presenting with watery diarrhea; however, the significance of this finding remains controversial, and adenoviral infection is not yet recognized as a significant cause of enteric disease in swine.(1)

In this case, histochemical staining with Warthin-Starry highlights numerous argyrophilic spirochetes adhered to the enteric mucosa, supporting a diagnosis of colonic spirochetosis, while the culture results as reported by the contributor definitively identify the etiologic agent as Brachyspira pilosicoli.

References:

1. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 2. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007:3-296.

2. Frey CF, Muller N. Tritrichomonas- systematics of an enigmatic genus. Mol Cell Probes. 2012;26:132-136.

3. Hampson DJ, Duhamel GE. Porcine colonic spirochetosis / intestinal spirochetosis. In: Straw BE, Zimmerman JJ, D'Allaire S, Taylor DJ, eds. Diseases of swine. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2006:755-783.Â

4. Jensen TK, Moller K, Boye M, Leser TD, Jorsal SE. Scanning electron microscopy and fluorescent in situ hybridization of experimental Brachyspira (Serpulina) pilosicoli infection in growing pigs. Vet Pathol. 2000;37:22-32.

5. Mostegl MM, Richter B, Nedorost N, Lang C, Maderner A, Dinhopl N, et al. First evidence of previously undescribed trichomonad species in the intestine of pigs? Vet Parasitol. 2012;185:86-90.

6. Rivera WL, Lupisan AJ, Baking JM. Ultrastructural study of a tetratrichomonad isolated from pig fecal samples. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:1311-1316.

7. Tachezy J, Tachezy R, Hampl V, Sedinova M, Vanacova S, Vrlik M, et al. Pathogen Tritrichomonas foetus (Riedmuller, 1928) and pig commensal Tritrichomonas suis (Gruby & Delafond, 1843) belong to the same species. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2002;49:154-163.