WSC 2022-2023:

Conference 16:

Case III:

Signalment:

2-month-old male entire Domestic Shorthair (Felis catus)

History:

A two-month-old kitten owned for 10 days with a history of diarrhoea and vomiting for the past 24 hours, presented with hypoglycaemia and agonal breathing. Arrested, cardiopulmonary resuscitation performed for 20 minutes, and owner consented for cessation.

Gross Pathology:

At postmortem examination, the lungs are mottled pale pink to dark red, spongy, with a bullous appearance to all distal margins (marginal emphysema) and have variably pale pink, approximately 0.8 cm wide linear discolouration (rib impressions, presumed related to CPR noted in history). The stomach contains a small amount of pale brown-green, pasty ingesta. The orad small intestines contain moderate amounts of thin, yellow fluid that transitions to pale cream digesta within the jejunum and scant cream-yellow digesta within the ileum. The colon contains pale brown, flocculent, variably mucoid, and watery faeces, and pale brown pasty faeces are within the rectum. The mesenteric lymph node is enlarged (4.0 x 1.2 x 0.3 cm, within normal limits for a kitten), and the ileocecal and colonic lymph nodes are similarly prominent.

Additional findings included: reduced subcutaneous adipose tissue stores, pale pink oral mucous membranes, a prominent (age-appropriate) thymus, heart measurements within normal ratio, mild lobular pattern on the liver, moderately distended gall bladder, kidney measurements within normal limits, congested meninges, and pale skeletal muscle.

No significant gross abnormalities are detected in the following tissues: sciatic nerve, coxofemoral joints, femur bone, femur bone marrow, thyroid gland, parathyroid glands, tongue, pharynx, larynx, great cardiac vessels, adrenal glands, ureters, eyes, and ears.

Laboratory Results:

Faecal PCR Panel: Negative (below assay detection limits) for the following organisms: Campylobacter, Salmonella, Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium [C. parvum, C. hominis], Tritrichomonas foetus, Toxoplasma gondii, Dientamoeba fragilis, Neospora caninum, Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin cpe, Parvovirus, Distemper virus, Feline and Canine Coronavirus.

Faecal flotation (Saturated sodium chloride, specific gravity 1.2): No evidence of eggs from nematodes or coccidia in the sample provided.

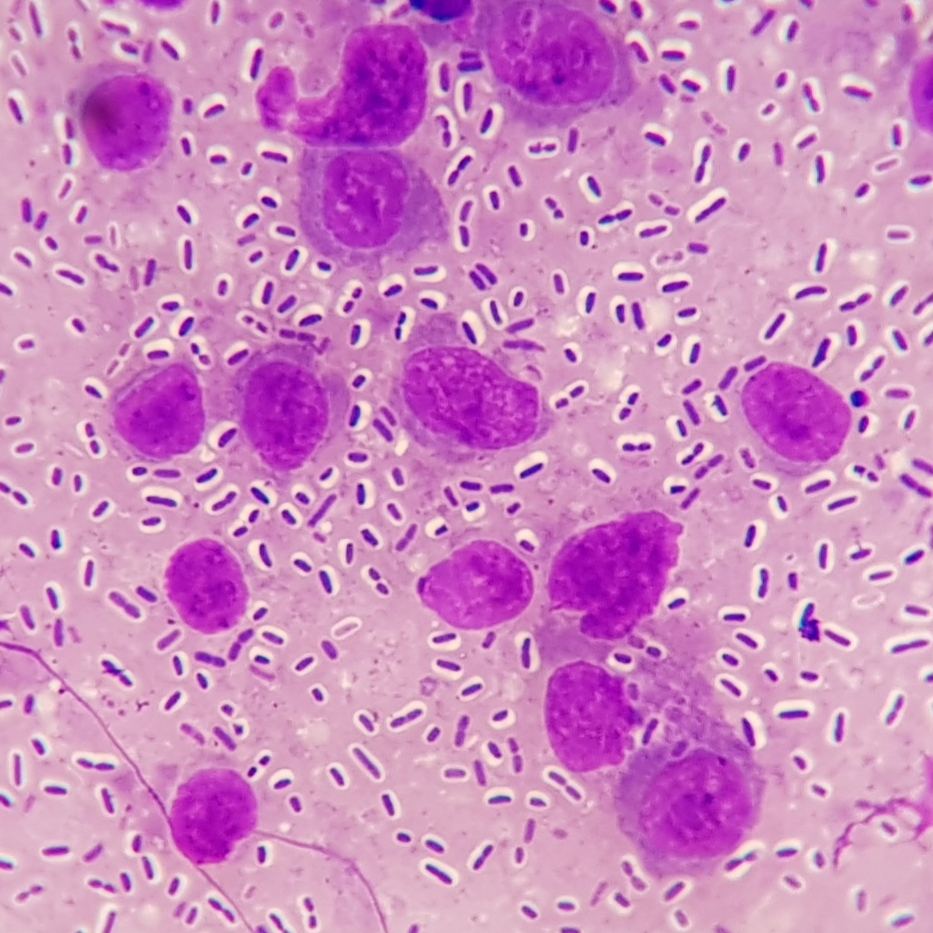

Microbiology: (spleen and liver): Samples of spleen and liver (collected at necropsy and frozen back for ancillary diagnostics if needed) were submitted for aerobic bacterial and fungal culture following initial histopathology review. After 24 hours incubation, cultures of both tissues yielded a pure heavy growth of a large, mucoid, lactose fermenting, non-haemolytic, Gram-negative rod with colony morphology that was circular, raised, mucoid, smooth, grey, and approximately 3 mm diameter in size. The IMViC and urease profile for the isolates were as follows: Indole negative, Methyl Red negative, Voges-Proskauer positive, Citrate positive, Urease positive. Microbiology comments: The biochemical profile and colony morphology of the isolates are consistent with Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, and isolate identification has been confirmed by bioMérieux API20E assay.

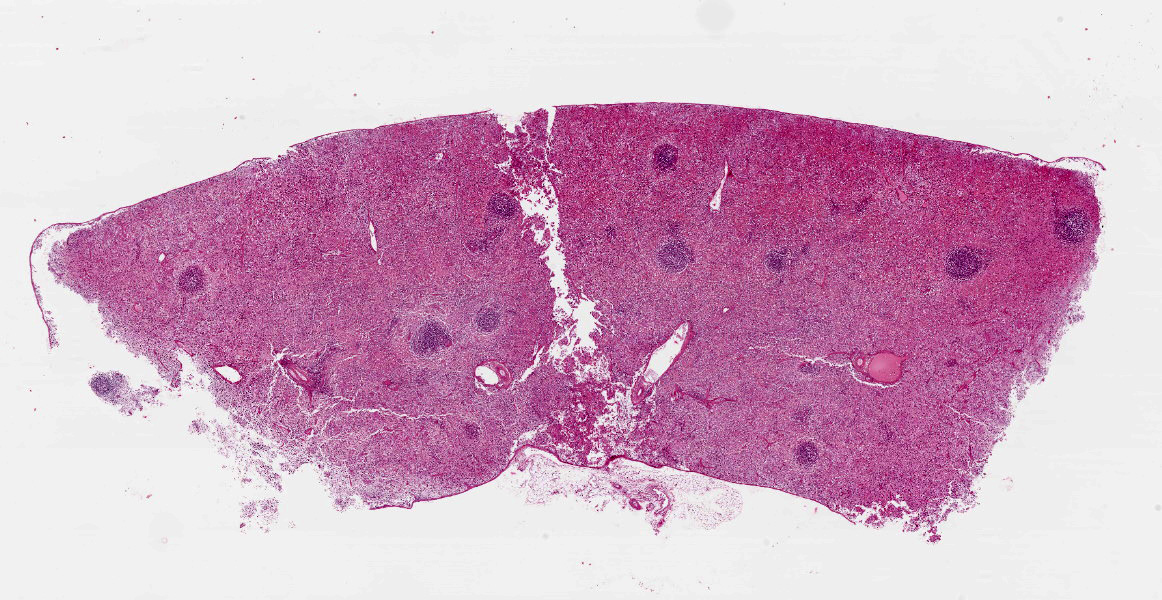

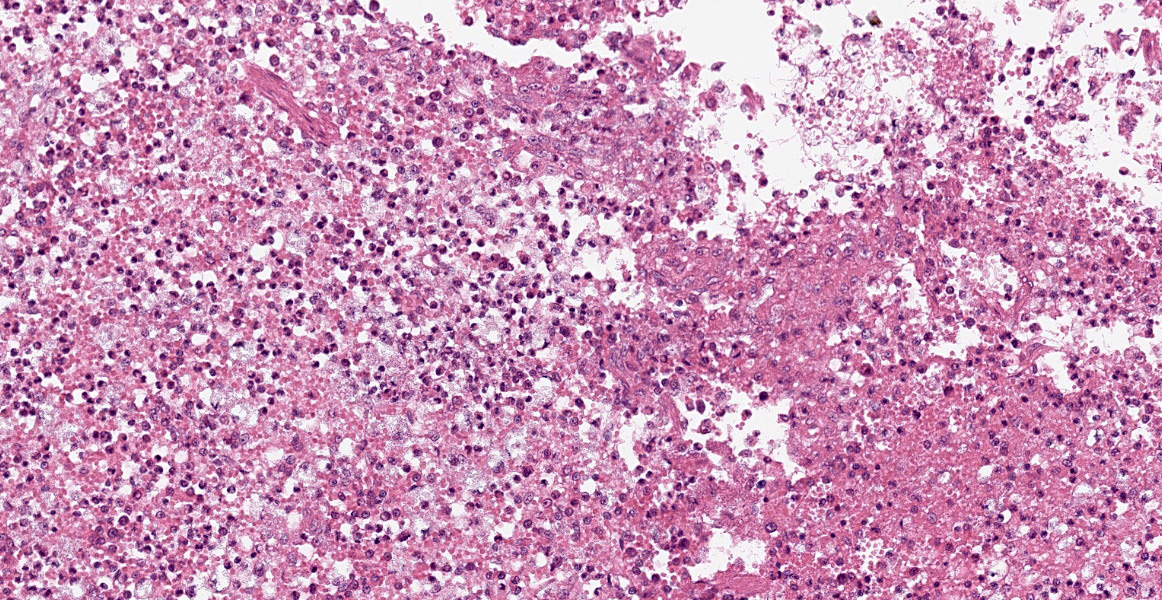

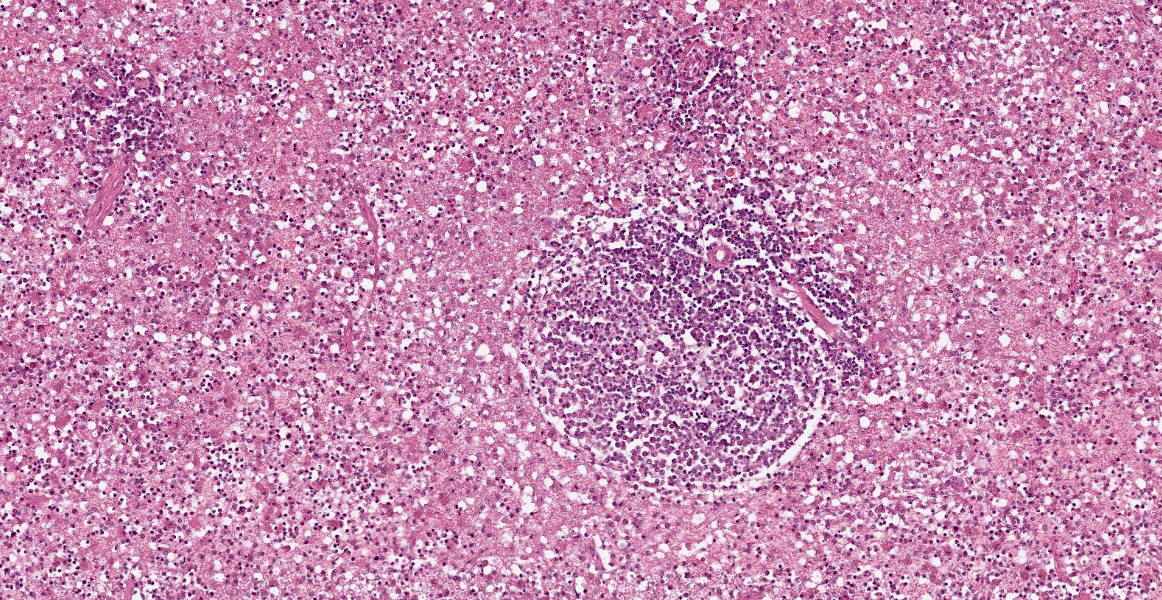

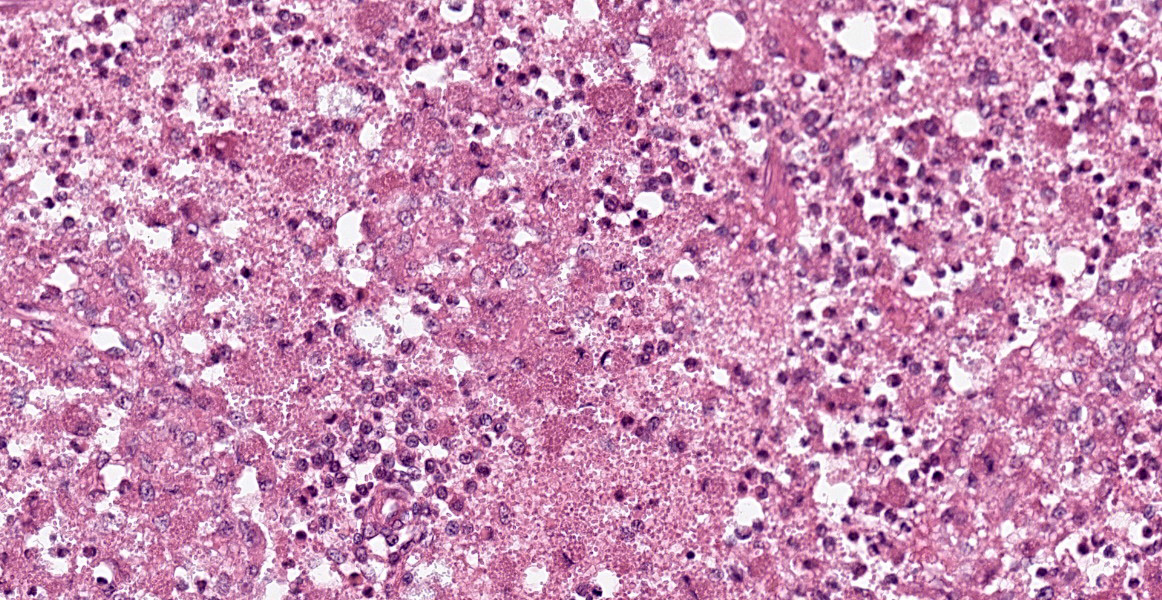

Microscopic Description:

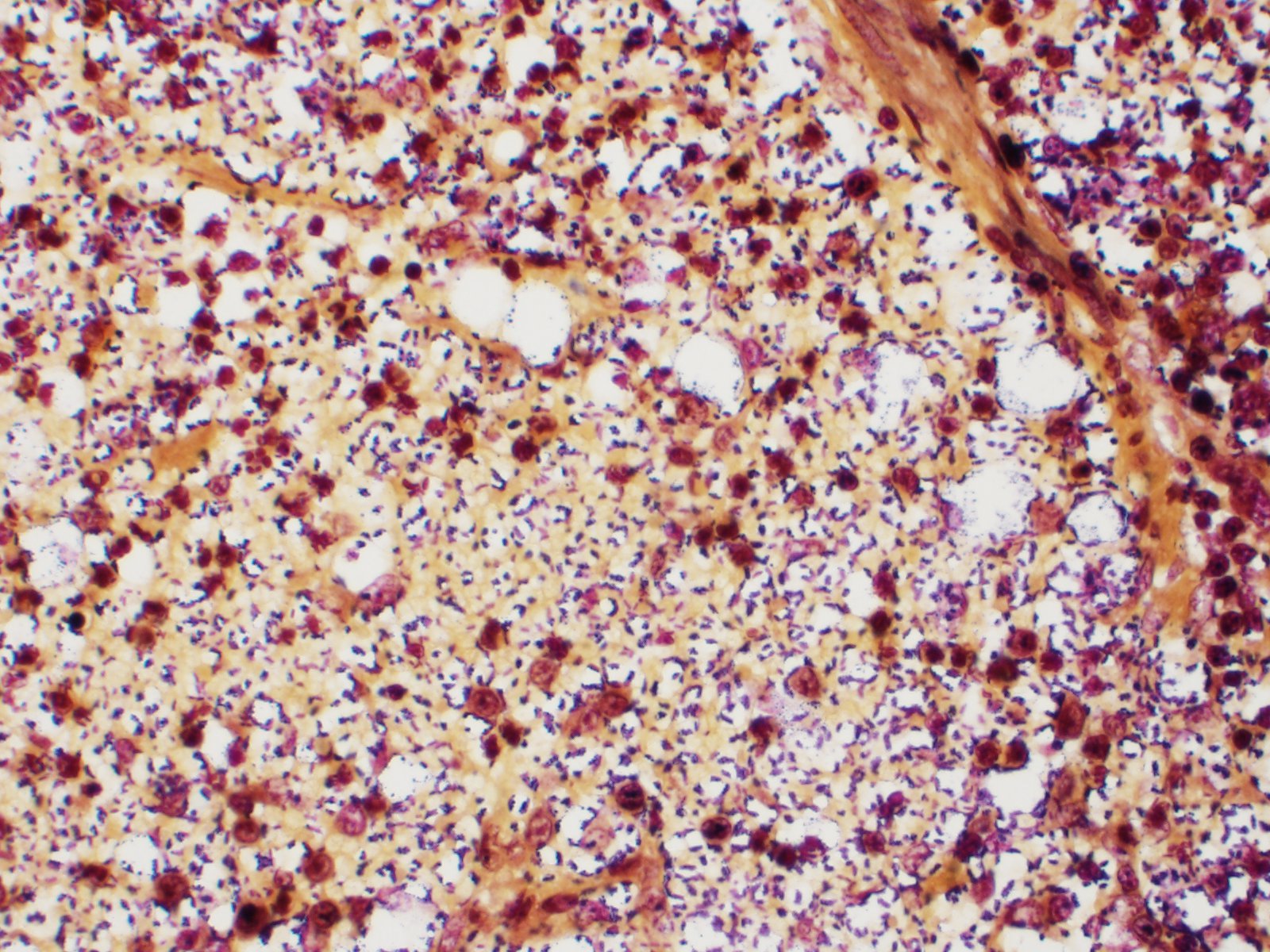

Spleen: White pulp follicles are smaller than expected and are widely separated by a hypercellular red pulp composed of erythrocytes interspersed with abundant homogenous eosinophilic material (presumed lysed erythrocytes), many macrophages and neutrophils, and myriad extracellular and intrahistiocytic bacterial rods, and scattered cellular debris and haematopoietic precursors. Additionally, throughout the sections, there are regionally extensive aggregates of approximately 2-4 micron round to ovoid discrete faintly eosinophilic structures with central round to elongate internal structures somewhat reminiscent of nuclei; Giemsa and Gram stained replicate sections reveal a similar staining pattern to the marked proliferations of bacteria elsewhere throughout the parenchyma (suggestive of ‘encapsulated’ bacteria).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Splenitis, diffuse, histiocytic and neutrophilic, acute to subacute, severe, with myriad extracellular and intrahistiocytic bacteria

Contributor’s Comment:

Morbidity and mortality were ascribed to fulminant Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae (Kpp) septicaemia and complications which most likely included multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Numerous encapsulated Gram-negative rods were evident histologically within the vasculature of all evaluated tissues and within the parenchyma of blood filtering organs. While some of this may be reflective of post-mortem overgrowth, the relatively short post-mortem interval combined with the identification of intracellular bacteria and acute inflammation in many tissues and heavy growth of pure cultures of Kpp isolated from spleen and lung support a diagnosis of severe antemortem bacteraemia. Kpp is an opportunistic bacterium found in the environment and as a commensal in the nasopharynx and alimentary tract of dogs and cats. Kpp can be associated with clinically significant infections of the respiratory, gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts and systemic bacteraemia in carnivores. In some instances, underlying immunosuppression appears to have played a role in disease development (e.g., drugs, malnutrition, stress, endocrine disease, and other infections, including feline leukaemia virus, feline immunodeficiency virus infection). Kpp-induced enteritis, pneumonia, and sepsis with concurrent MODS has been reported in dogs. The diarrhoea and enteritis in this kitten were presumably related. Pneumonia was of sufficient severity to have resulted in some degree of respiratory compromise which was likely further exacerbated by SIRS, accounting for the clinically noted respiratory distress. In the medical and veterinary microbiology literature, the most common pathogenic bacteria that have capsules linked to virulence include are Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Yersinia pestis and Bacillus antracis, where only the first four are gram-negative.6

Contributing Institution:

University of Sydney

https://sydney.edu.au/science/schools/sydney-school-of-veterinary-science/veterinary-science-services.html

JPC Diagnosis:

Spleen: Splenitis, histiocytic and neutrophilic, diffuse, severe with lymphoid depletion, congestion, and innumerable extracellular and intrahistiocytic bacilli.

JPC Comment:

Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with community-acquired, opportunistic, and nosocomial infections in both humans and animals and is one of the leading causes of healthcare-associated infections in humans. There are a wide range of virulence factors which contribute to its pathogenicity. Kpp has 78 distinct capsular serotypes, but K1 and K2 are the most commonly isolated.3,4 Its capsule prevents phagocytosis, blocks opsonization, and prevents complement-mediated lysis.3 To acquire necessary iron, Kpp produces several sidephores, including enterobactin, yersiniabactin, salmochelin, and aerobactin.3 Adhesins and type 1 and 3 fimbriae facilitate adhesion, invasion, and biofilm formation. Biofilms form on indwelling devices (such as catheters) and facilitate colonization of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and urinary tracts.3 Kpp utilizes quorum sensing to coordinate gene expression at certain bacterial densities.3 Additionally, a hypervirulent strain of K. pneumoniae (hvKp) has emerged and is associated with serious community-acquired infections in humans, causing pneumonia, hepatic abscesses, meningoencephalitis, and septic arthritis.3,4 This strain produces excess capsular material, causing hypermucosity, and higher quantities of siderophores than the classic strains.3

K. pneumoniae naturally produces chromosomal penicillinases, conferring resistance to ampicillin, carbenicillin, and ticarcillin; in the past four decades, however, K. pneumoniae has also collected additional antibiotic resistance plasmids, expanding its antibiotic resistance repertoire. Some strains are now developing resistance to carbapenem, previously considered a first-line treatment for this infection.3

A recent retrospective study of infections in 697 domestic animals in Brazil provides a glimpse of the spectrum of diseases caused by K. pneumoniae.4 The urinary system was the most common system affected in dogs and cats, accounting for 51.9% of 393 canine cases and 63% of 27 feline cases; the infection caused cystitis, pyelonephritis, and urethritis in these species.4 In cattle, 59.7% of 149 cases were due to mastitis; the majority of these were clinical and considered moderate to severe.4 In 53.1% of 98 cases in horses, the bacteria was associated with reproductive infection, causing seminal vesiculitis, pyometra, abortion, and orchitis. In pigs, 59.1% of 22 cases were associated with diarrhea.4

References:

- Green CE, Sykes J. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:187-188.

- Koenig A. Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. In: Green CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2012: 353-355.

- Piperaki ET, Syrogiannopoulos GA, Tsouvelekis LS, Daikos GL. Klebsiella pneumoniae: Virulence, Biofilm and Antimicrobial Resistance. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2017; 36(10): 1002-1005.

- Ribiero MG, de Morais ABC, Alves AC. Klebsiella-induced infections in domestic species: a case-series study in 697 animals (1997-2019). Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2022; 53: 455-464.

- Roberts DE, McClain, HM, Hansen, DS, Currin P, Howerth, EW. An outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in dogs with severe enteritis and septicemia. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000; 12:168-173.

- Tortora GJ, Funke BR, Case CL. Microbiology: An Introduction. 9th ed. San Francisco, CA: Pearson Benjamin Cummings.