CASE I: Z215/20 (JPC 4167239)

Signalment:

Adult (>3 year-old), male, red-chested mustached tamarin, Saguinus labiatus.

History:

Bauru Zoo has a new world primate (NWP) population ranging from 30 to 55 individuals over the past eleven years (2010-2020), with 16 different species of genre Alouatta, Ateles, Callicebus, Lagothrix, Leontopithecus and Saguinus. Since 2010, there were 27 deaths associated with Prosthenorchis sp. parasitism, representing 67.5% of total deaths of tamarins and lion tamarins (27/40) and 49.1% of deaths in all NWP (27/55). Deaths associated to parasitism were reported in seven years (2010, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016, 2019 and 2020) with an average of one case per year over the first nine years (2010-2018), and a marked increase in the number of deaths over the last two years (2019-2020) with an average of nine cases per year. All deaths associated to Prosthenorchis sp. parasitism affected tamarins and lion tamarins, including 18 (66.7%) belonging to the genus Saguinus (15 S. bicolor, two S. labiatus and one S. niger) and nine (33.3%) belonging to the genre Leontopithecus (four L. rosalia, four L. chrysomela and one L. chrysopygus).

Gross Pathology:

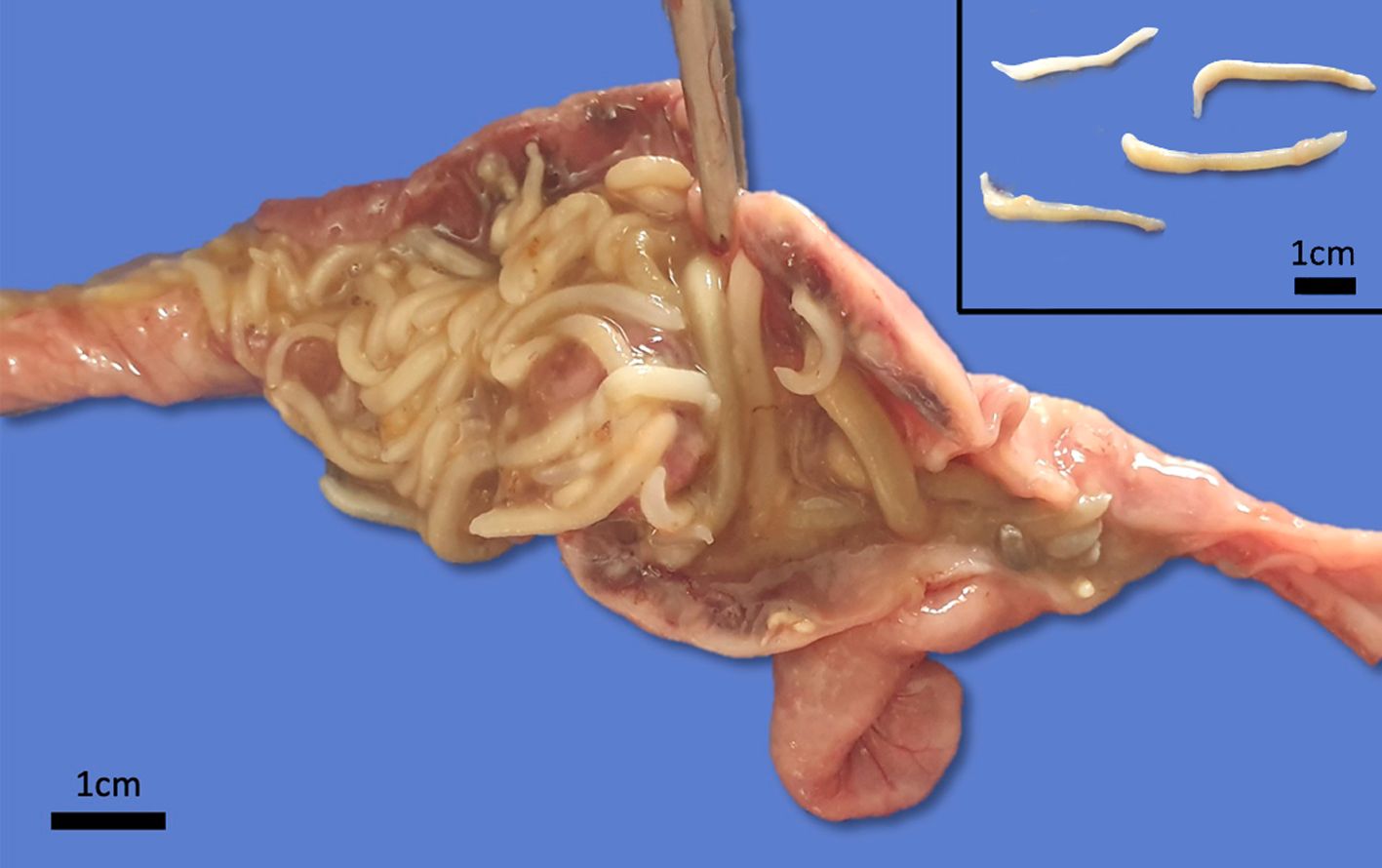

Grossly, there were multiple yellowish to gray soft nodules disseminated on the serosa of the ileum, cecum and colon, with 0.2 a 0.5 cm in diameter. In the intestinal lumen there were dozens of cylindrical adult parasites deeply attached to the mucosa, morphologically compatible with acanthocephalan, and the intestine wall was diffusely thick and edematous. Additionally, the animal had severe cachexia.

Laboratory Results:

None.

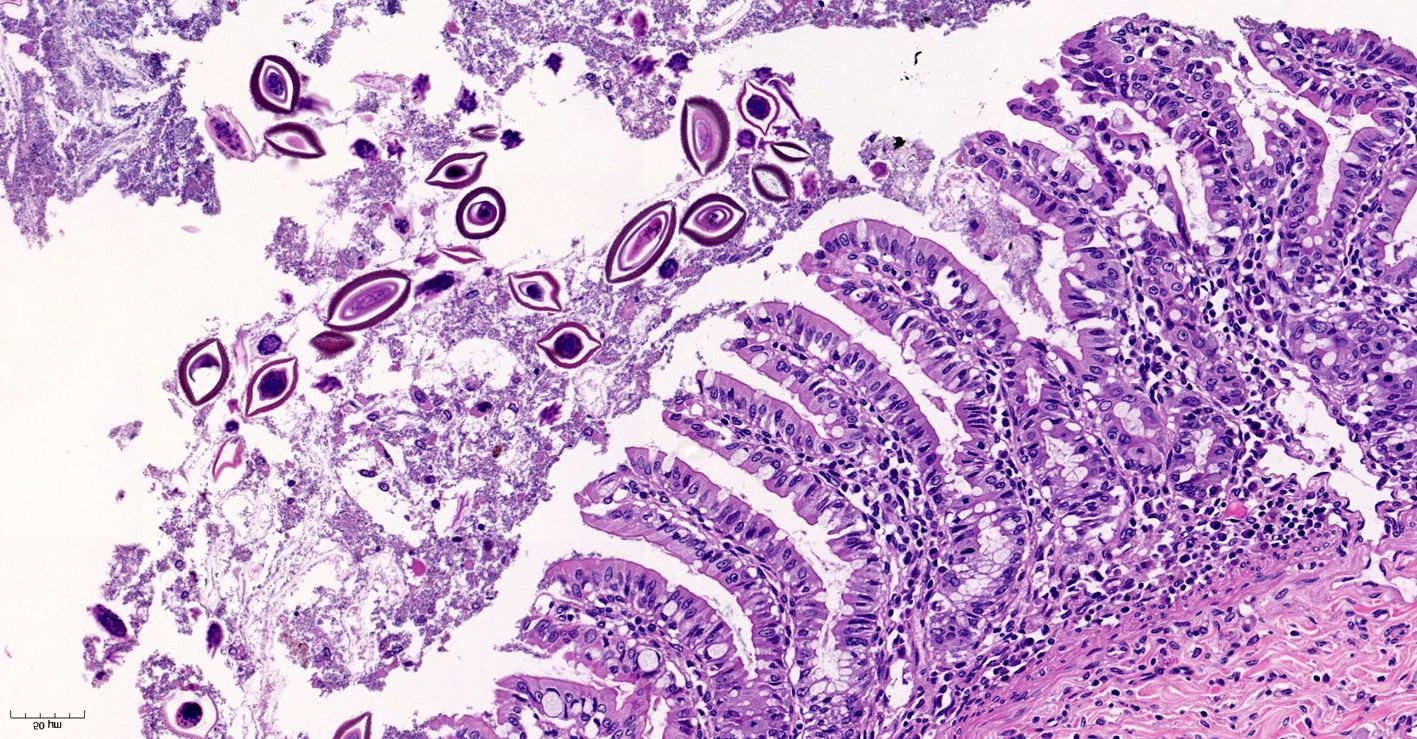

Microscopic Description:

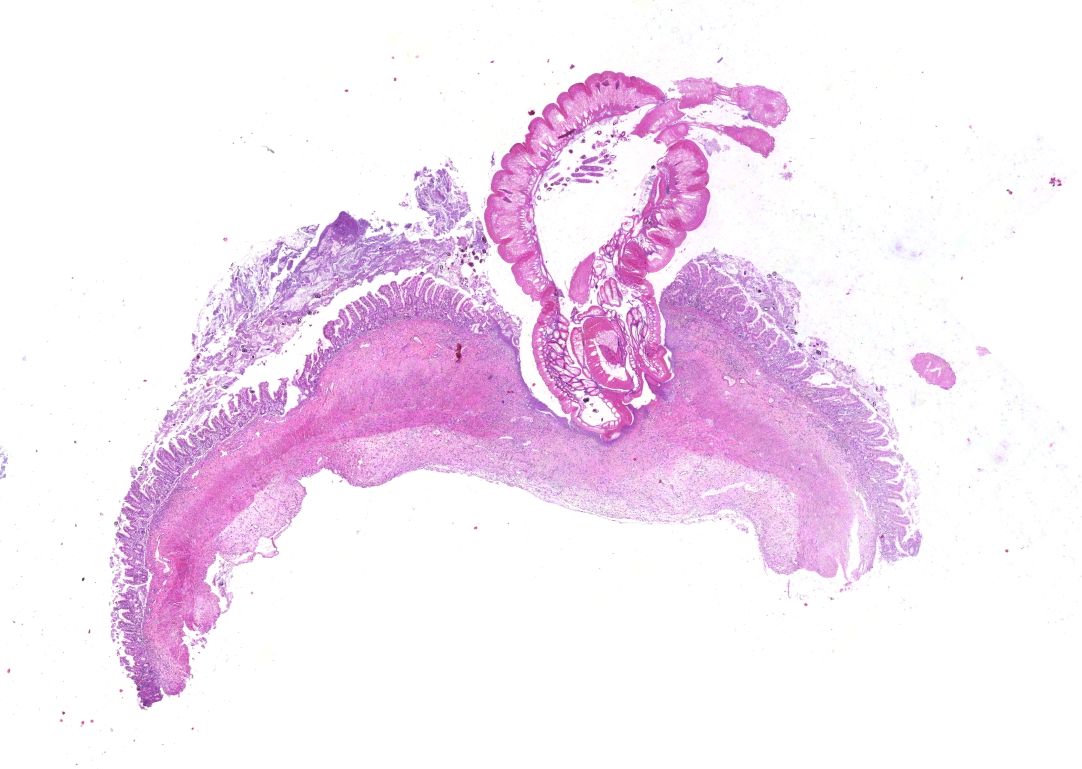

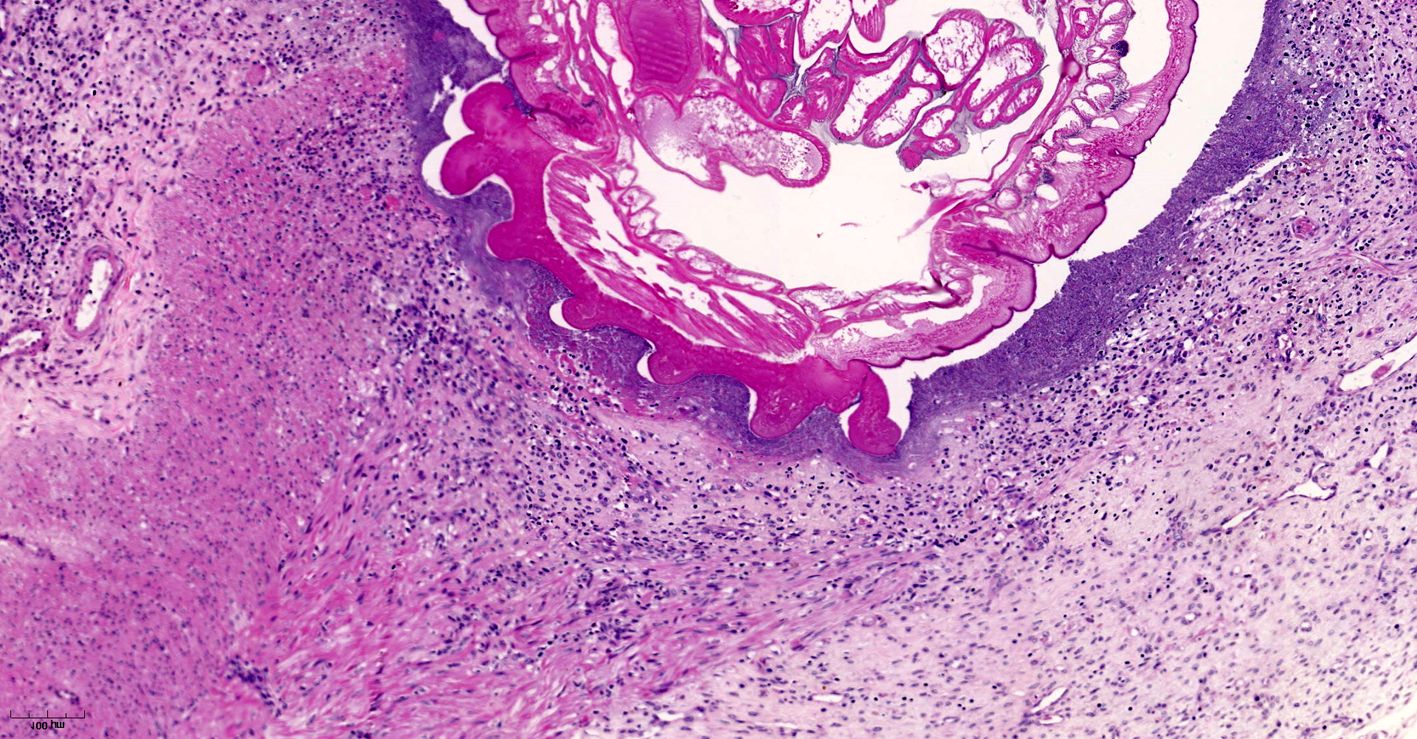

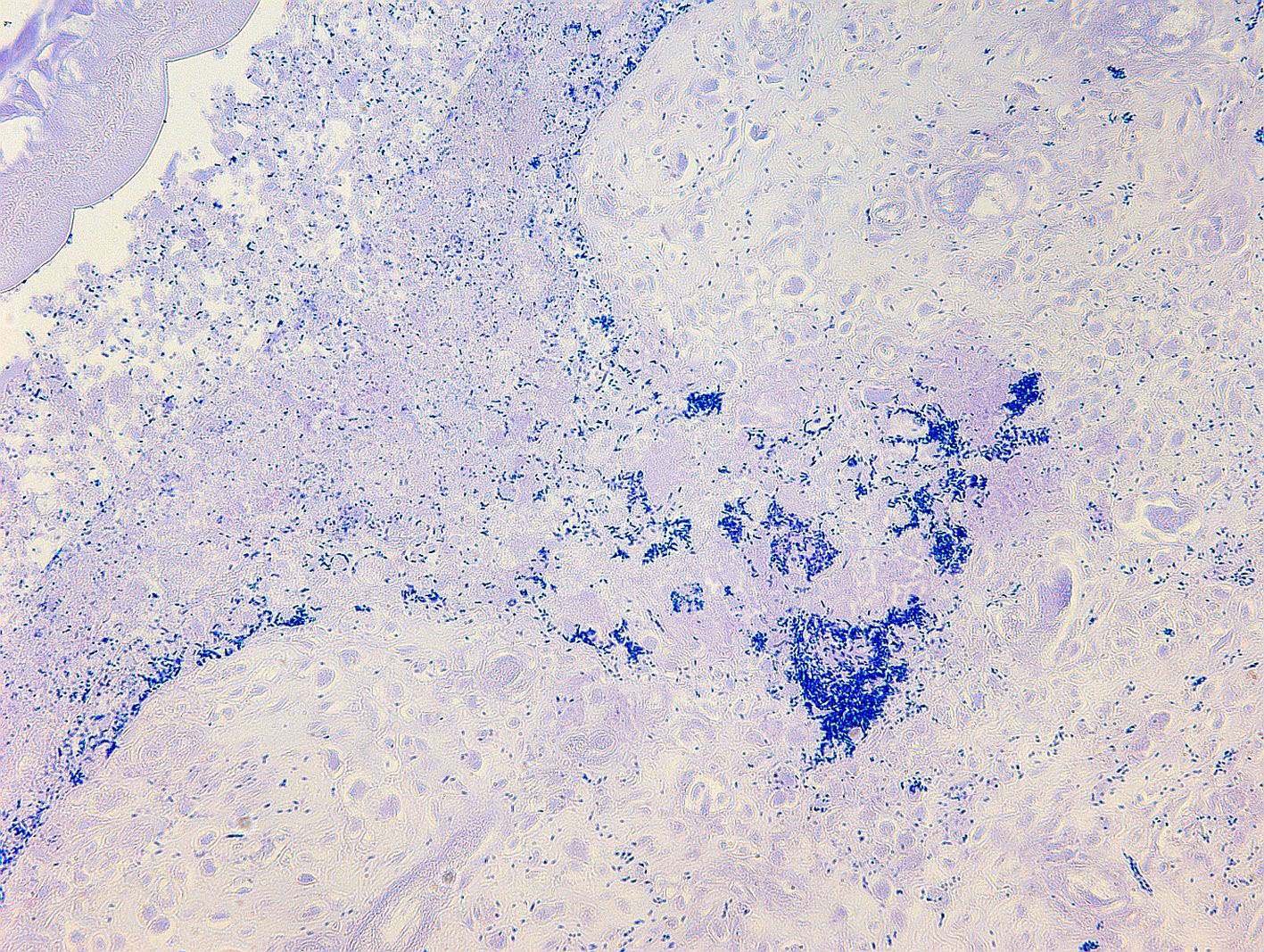

Small intestine. Focally extensive area of ulceration extending into the mucosa, submucosa and muscular layers with a moderate and diffuse lymphohistioplasmacytic and neutrophilic infiltrate, marked fibroplasia, and an intralesional acanthocephalan parasite. There is a longitudinal section of an adult parasite with a delicate cuticle, a thick hypodermis, a thin muscular layer, and a pseudocoelomatic cavity filled with a uterus with multiple eggs, which is morphologic compatible with an adult female acanthocephalan parasite. The acanthocephalan is deeply attached to the intestine wall by its hooks, which are inserted deeply at the external intestinal muscular layer. Both transversal and longitudinal intestinal muscular layers are completely lost. There are myriad of bacteria within the path of parasite migration within the intestine wall. There are many acanthocephalan eggs in the intestinal lumen. The serosa is diffusely thick, edematous, with ectasia of lymphatic vessels.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Small intestine: Ulcerative and necrotizing enteritis, transmural, chronic, with intralesional acanthocephalan parasite.

Contributor's Comment:

Acanthocephalan parasitism in NWP is known to be an important cause of malnutrition and death in captivity. Once established in a colony it is extremely difficult to control or eliminate from the environment.8,12,17 Prosthenorchis sp. are acanthocephalan parasites found in the small and large intestines (ileum, cecum and colon) of different mammalian species,2,5 and have been reported in captive and free-ranging NWP, with two species recognized to infect this group of animals: P. elegans and P. spirula.2

NWP are the definitive hosts of this parasite, and the infection occurs by ingesting intermediate hosts, including cockroaches and beetles, carrying the infective larvae. Usually, captive primates are infected by ingestion of intermediate hosts that may be offered as environmental enrichment or found inside the enclosures as environmental pests.17 A feature of acanthocephalans, including Prosthenorchis sp., is a well-developed proboscis that attaches deep in the intestinal mucosa.1,9-12 It feeds on the intestinal content by osmosis, reducing the absorption of nutrients by the host, which in chronic infections results in malnutrition and cachexia.8,9,11,12 In some cases, this parasite can perforate the intestine wall and be found free in the abdominal cavity, causing a severe and acute peritonitis, which leads to a quick death.1,11,12 In addition, acanthocephalan parasitism favors bacterial translocation and secondary bacteremia, which usually contributes to clinical impairment of the animal.8

There is a wide variety of feeding habits among NWP, ranging from folivorous to omnivorous.17 Therefore, although acanthocephalan parasitism may affect any genus of NWP, some species are more predisposed to be parasitized by Prosthenorchis sp. due to their feeding habits. For instance, Saguinus and Leontopithecus have approximately 80% of their diet composed of fruits, and the remaining of the diet includes insects, small vertebrates, nuts, and nectar, according to availability.3,9,13 These species also have dentition more adapted to predate small vertebrates and insects,17 justifying the high prevalence of this parasitism in these genera.

It is known that wild tamarin groups that have more contact with anthropic environment tend to have a higher prevalence of P. elegans,18 although the parasite seems to be less pathogenic for free-ranging animals.15 Indeed, acanthocephalan parasitism has being often reported affecting free-ranging NWP in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, particularly in peri-urban areas.1,10,16 Tamarins and lion tamarins are found in all Latin America and some of them, such as S. bicolor, are critically endangered.6,14 Therefore, it is essential for a successful conservation strategy to better understand the threats for the survival of these species, both in captivity and in wildlife, including acanthocephalan parasites.

Contributing Institution:

Departamento de Clínica e Cirurgia Veterinária, Escola de Veterinária, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Av. Presidente Antônio Carlos, 6627 ? CEP 30161-970, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

JPC Diagnosis:

Ileum: Enteritis, necrotizing and pyo-granulomatous, transmural, chronic, severe, with acanthocephalid adult and eggs.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a concise review of host factors and the pathogenesis associated with acanthocephalan parasitism in NWMs.

Phylum Acanthocephala is a diverse group of over 1,100 species of pseudocoelomates colloquially known as "thorny-headed worms" due to their characteristic proboscis with hook-like projections used to anchor the parasite to the host's gastrointestinal tract.4,7 As noted by the contributor, these parasites have a complex life cycle with intermediate and definitive hosts. Arthropods such as crustaceans and insects serve as intermediate hosts, which are in turn ingested by definitive and/or paratenic vertebrate hosts such as reptiles, amphibians, fish, birds, marine and terrestrial mammals, and humans.7,19

Acanthocephalans are readily identifiable from other metazoan parasites in histologic sections by the combined features of a pseudocoelom, an anterior end armed with a proboscis, and the absence of a digestive tract. Additional characteristic features include a thin peripheral cuticle, thick hypodermis composed of a subcuticular felted layer and thicker inner layer of cross fibers occasionally interrupted by lacunar channels, and two layers of muscle (circular and longitudinal) bordering the pseudocoelom. Acanthocephalans are dioecious, with females containing both immature ova also known as "egg balls" and embryonated eggs within the pseudocoelom whereas males contained paired testes. Finally, acanthocephalans possess a unique structure known as lemniscus that plays a role in the eversion and retraction of the proboscis.4 In the case of Prosthenorchis spp., the worms are most commonly found attached to the luminal aspect of the terminal ileum, cecum, and colon, typically within a nodule.1

Acanthocephalan eggs have been discovered in copralites from prehistoric humans, indicating acanthocephaliasis may be an ancient disease of humans. Humans continue to be infected during the modern era, most commonly by Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus, M. ingens, and Moniliformis moniliformis, which parasitize pigs, raccoons, and rodents as their primary definitive hosts, respectively. The majority of cases involve children, likely as the result of putting objects such as insects, in their mouths. Insects and arthropods used for medicinal purposes have also been linked to human infections. Finally, humans may also become infected by consuming paratenic hosts, as is suspected with Bolbosoma spp. infection. Cetaceans are considered definitive hosts of this genus, while marine planktonic crustaceans and fish likely serve as intermediate and paratenic hosts, respectively.7

Conference participants reviewed the previously discussed features of acanthocephalans in addition to those of other metazoan parasites while discussing this case. Unfortunately, the highly characteristic feature of an armed proboscis with hook-like projections was not in the plane of section. Nevertheless, the presence of a pseudocoelom and absence of a gastrointestinal tract is diagnostic for an acanthocephalan. Based on the patient's signalment and clinical history, the moderator agreed the acanthocephalan in this case is most likely Prosthenorchis elegans. However, the moderator cautioned against attempts to definitively identify the species, and in many cases the genus, of metazoan parasites based solely on histologic sections.

References:

1. Catenacci LS, Colosio AC, Oliveira LC, et al. Occurrence of Prosthenorchis elegans in free-living primates from the Atlantic Forest of southern Bahia, Brazil. J Wildl Dis. 2016;52:364-368.

2. Falla AC, Brieva C, Bloor P. Mitochondrial DNA diversity in the acanthocephalan Prosthenorchis elegans in Colombia based on cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene sequence. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2015;4:401-407.

3. Gaber PA. Seasonal patterns of diet and ranging in two species of tamarin monkeys: Stability versus variability. Int J Primatol. 1993;14: 145?166.

4. Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues, American Registry of Pathology. Washington, DC, 1999: 1,44-45.

5. Gomes APN, Olifiers N, Souza JGR, Barbosa HS, D'Andrea PS, Maldonado Jr. A. A new acanthocephalan species (Archiacanthocephala: Oligacanthorhynchidae) from the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) in the Brazilian Pantanal Wetlands. J Parasitol. 2015;101(1):74?79.

6. Gordo M, Röhe F, Vidal MD, et al. Saguinus bicolor (amended version of 2019 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T40644A192551696.2021; Accessed on 02 June 2021.

7. Mathison BA, Mehta N, Couturier MR. Human Acanthocephaliasis: a Thorn in the Side of Parasite Diagnostics. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59(11):e0269120. doi:10.1128/JCM.02691-20

8. Monteiro RV, Dietz JM, Jansen A. The impact of concomitant infections by Trypanosoma cruzi and intestinal helminths on the health of wild golden and golden-headed lion tamarins. Res Vet Sci. 2010;89(1):27-35.

9. Müller B, Mätz-Rensing K, Yamacita JGP, Heymann EW. Pathological and parasitological findings in a wild red titi monkey, Callicebus cupreus (Pitheciidae, Platyrrhini). Eur J Wildl Res. 2010;56:601?604.

10. Oliveira AR, Hiura E, Guião-Leite FL, et al. Pathological and parasitological characterization of Prosthenorchis elegans in a free-ranging marmoset Callithrix geofroyi from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Pesq Vet Bras. 2017;37(12):1514-1518.

11. Pérez-García J, Ramírez DM, Hernández CA. Prosthenorchis sp. em titíes grises (Saguinus leucopus). Rev CES/Med Vet y Zootec. 2007;2: 51?57.

12. Pissinatti L, Pissinatti A, Burity CHF, Mattos Jr. DG, Tortelly R. Ocorrência de Acanthocephala em Leontopithecus (Lesson, 1840), cativos: aspectos clínico- patológicos. Callitrichidae-Primates. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2007;59(6):1473-1477.

13. Raboy BE, Dietz JM. Diet, foraging, and use of space in wild golden-headed lion tamarins. Am J Primatol. 2004;63(1):1-15.

14. Rylands AB, Heymann EW, Alfaro JL, et al. Taxonomic review of the New World tamarins (Primates: Callitrichidae). Zool J Linn Soc. 2016;177(4):1003-1028.

15. Soto-Calderón ID, Acevedo-Garcés YA, Álvarez-Cardona J, Hernández--Castro C, García-Montoya G. Physiological and parasitological implications of living in a city: the case of the white-footed tamarin (Saguinus leucopus). Am J Primatol. 2016;78:1272-1281.

16. Tavela AO, Fuzessy LF, Silva VHD, Carretta Jr M, Silva IO, Souza VB. Helminths of wild hybrid marmosets (Callithrix sp.) living in an environment with high human activity. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2013;22:391-397.

17. Verona CE, Pissinnatti A. Capítulo 34: Primates ? Primatas do Novo Mundo (sagui, macaco-prego, macaco-aranha, bugio e muriqui). In: Cubas ZS, Silva JCR, Catão-Dias JL, eds. Tratado de Animais Selvagens ? Medicina Veterinária Volume 1. 2nd ed. São Paulo, BR: Editora Roca Ltda; 2014:723-743.

18. Wenz A, Heymann EW, Petney TN, Taraschewski HF. The influence of human settlements on the parasite community in two species of Peruvian tamarin. Parasitol. 2010;137:675-684.

19. Zittel M, Grabner D, Wlecklik A, et al. Cryptic species and their utilization of indigenous and non-indigenous intermediate hosts in the acanthocephalan Polymorphus minutus sensu lato (Polymorphidae). Parasitology. 2018;145(11):1421-1429.