Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 7, Case 1

Signalment:

21-year old, female intact, Trakehner horse (Equus caballus)History:

Gross Pathology: Both rear metacarpophalangeal joints are enlarged with thick, fibrous joint capsules but no effusion. The branches of the rear suspensory ligaments are enlarged to approximately twice the diameter of the front suspensory ligament branches, and they are mottled yellow, tan, and white on cut section.Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

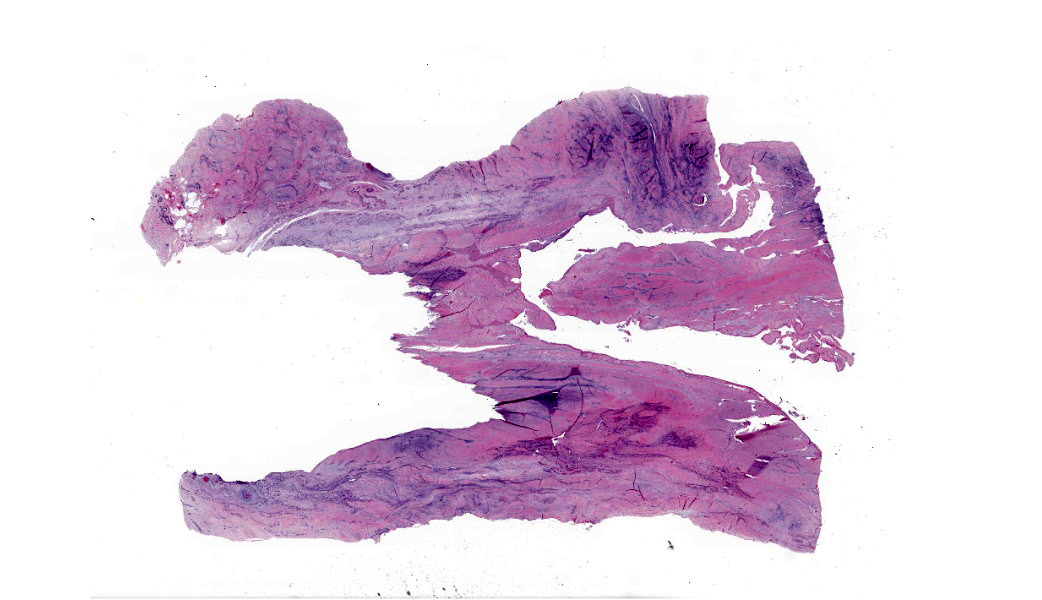

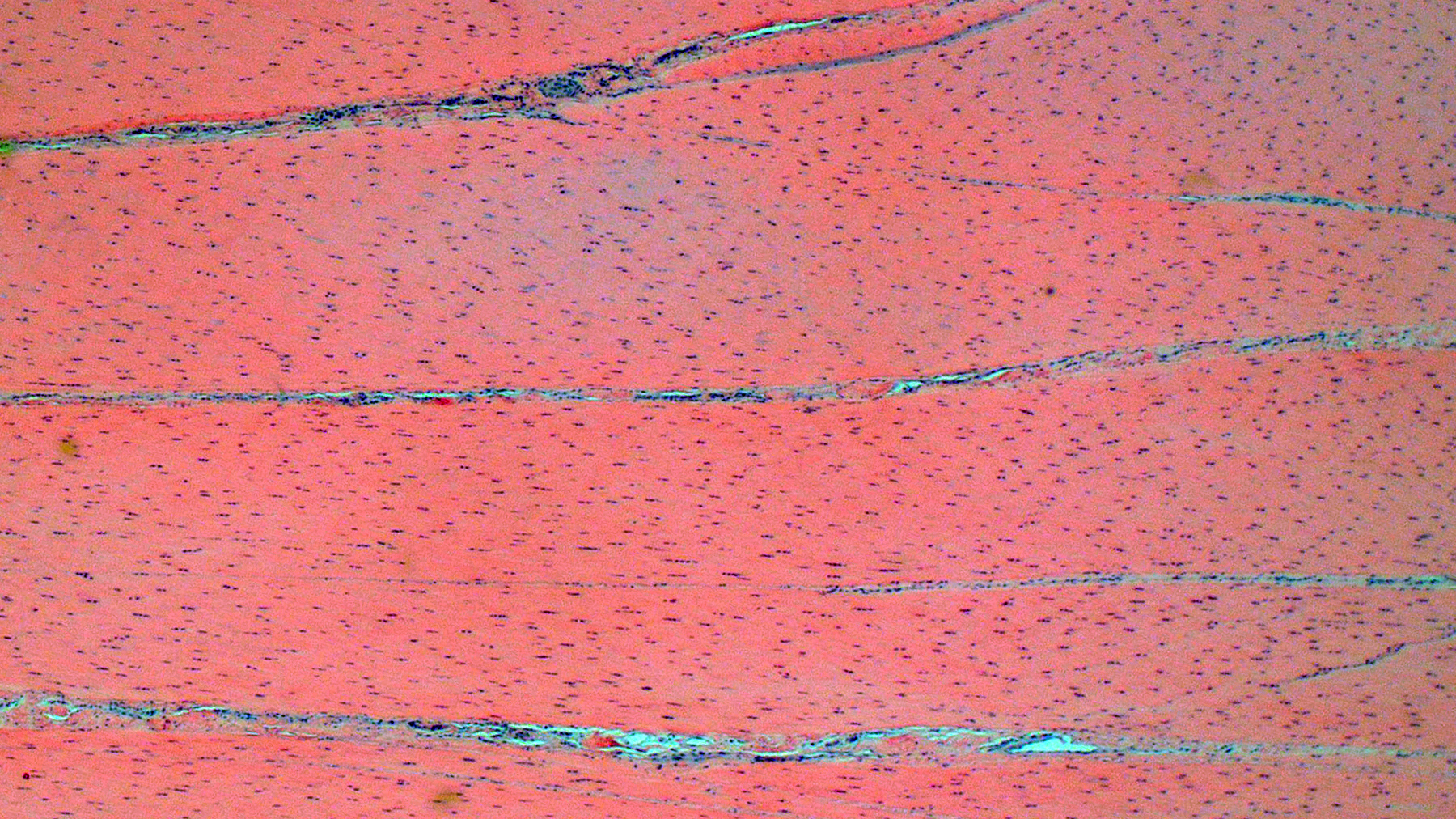

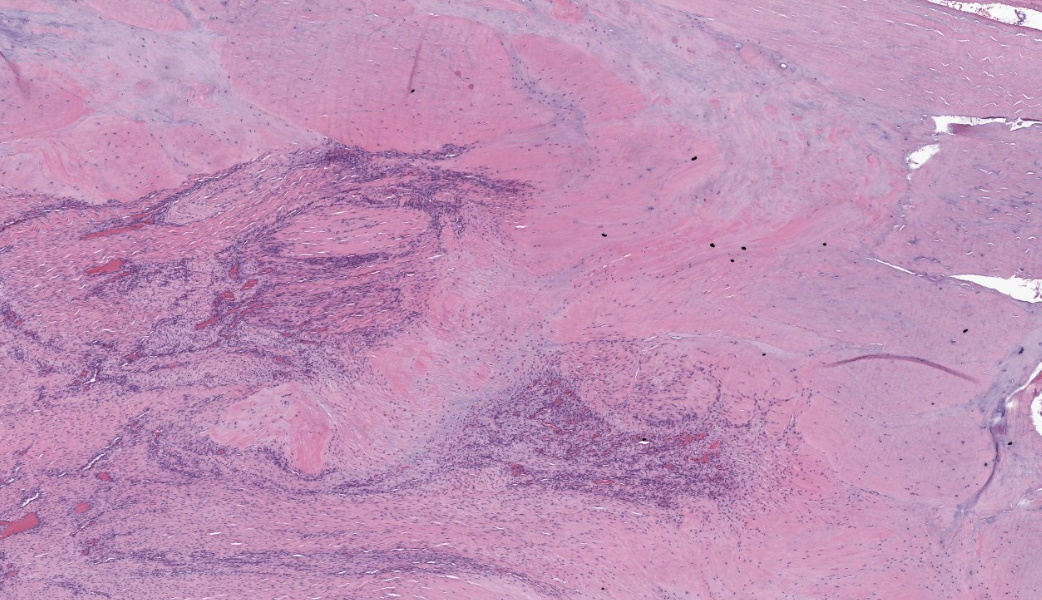

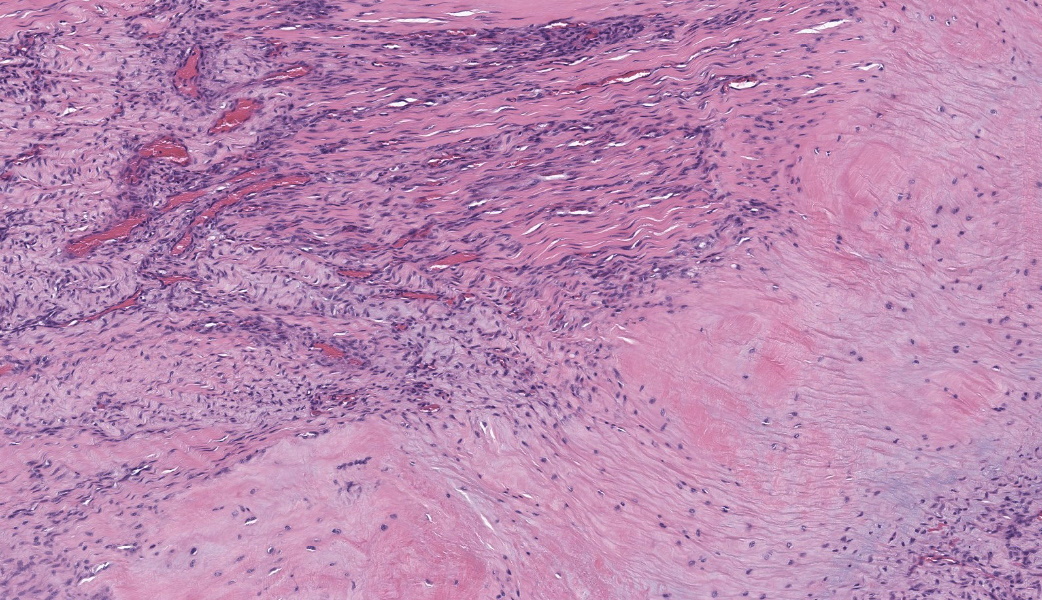

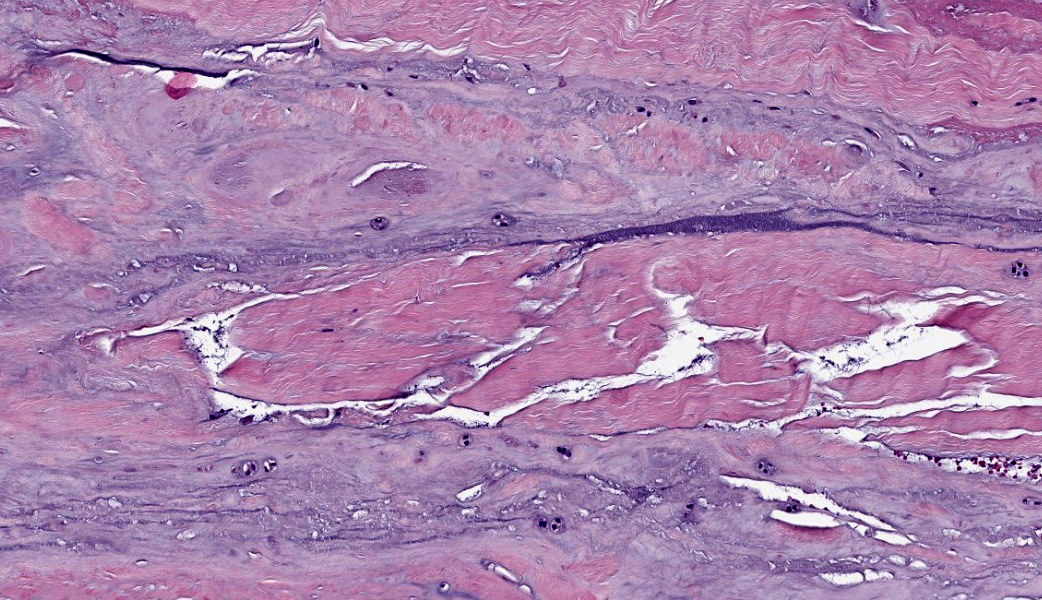

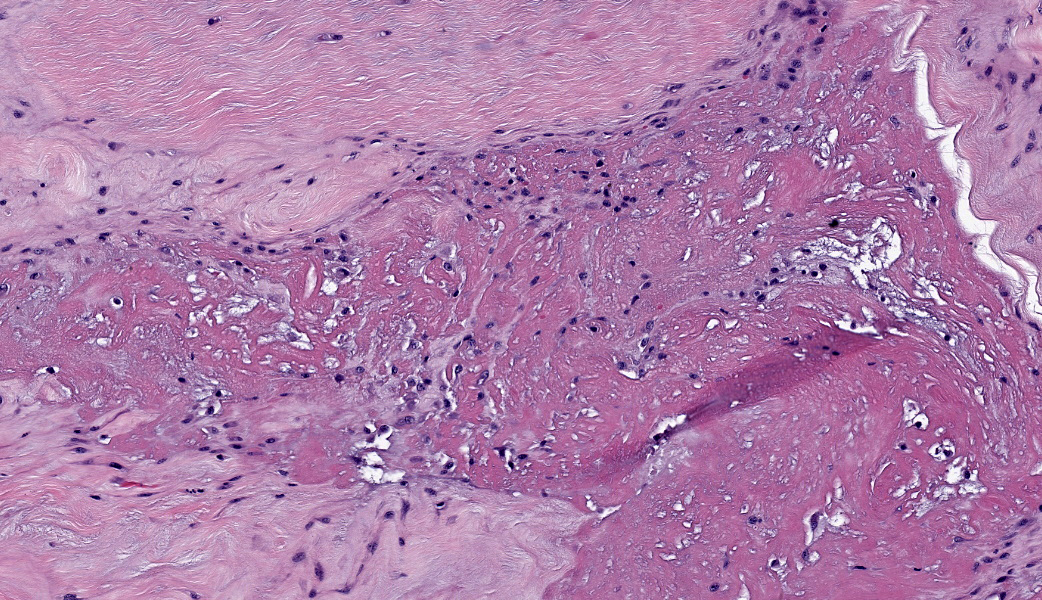

Suspensory ligament, right rear branch. Compared to a branch of the clinically normal right front suspensory ligament, collagen fibers are irregular and often form intersecting or divergent bundles. In many areas, there are fewer fibroblasts among collagen fibers than in the normal control. Throughout the tissue, wavy tendrils of pale basophilic, Alcian blue-positive matrix dissect between collagen bundles. Similar material surrounds increased numbers of variably sized, dilated and tortuous blood vessels. These vessels have thin walls and are lined by plump endothelial cells, and are often surrounded by loosely arranged stellate cells. In other areas, there is chondroid metaplasia, with clustered and individual chondrocyte-like cells in lacunae surrounded by amorphous, pale basophilic matrix, which is sometimes faintly mineralized. There is rare hemorrhage.Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Severe chronic extensive suspensory ligament degeneration with chondroid metaplasia and vascular proliferationContributor's Comment:

The terms degenerative suspensory ligament desmitis (DSLD) and suspensory ligament degeneration (SLD) are used somewhat synonymously, with DSLD often used to describe horses with a clinical diagnosis of suspensory ligament degeneration, and SLD used to describe histologic findings in the suspensory ligaments of horses that may or may not have a clinical diagnosis of DSLD. DSLD causes chronic, progressive multi-limb lameness of variable severity, often recognized by enlarged, hyperextended or dropped fetlocks.8 The rear limbs are typically more affected.3,8 In addition, the terms suspensory ligament desmitis or suspensory ligament desmopathy may be used to describe any of a variety of clinically or ultrasonographically detected injuries anywhere along the length of the suspensory ligament.3 Histology is rarely performed in these cases, especially in the acute phase, and it is unclear if these injuries are related to degenerative changes.3Histologic changes in SLD/DSLD include loss of longitudinal arrangement of collagen fibers, proteoglycan accumulation, presence of chondrocytes, hemorrhage, vascular proliferation, and widened interstitial connective tissue septa.4,6 Despite the use of the term desmitis, inflammatory cells are not present.4 These changes are reported to be more severe in the branches of the suspensory ligament than in the body or origin of the ligament.3,5

The pathogenesis of SLD/DSLD is incompletely understood. It has been associated with athletic function, broodmare status, and old age, but strong breed predispositions to DSLD, particularly in the Peruvian Paso, suggest a hereditary basis in many cases.8 In one recent genome-wide association study of single nucleotide polymorphisms in different breeds of horse, several candidate loci were identified among genes which are related to collagen synthesis, tendon aging, mechanotransduction, signaling, and metabolism.9 However, a single gene has not been identified as causative, and the disease is assumed to be polygenic and multifactorial.9

One avenue of investigation also suggests an association between SLD and pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID), which may be similar to the Achilles tendinopathy that rarely occurs in humans with Cushing?s syndrome.1,5,6 Endogenous or exogenous glucocorticoid excess can lead to various changes in collagen, proteoglycans, and matrix metalloproteinases and result in connective tissue weakness.1,5,6 The exact mechanisms in affected humans and horses are unknown; however, horses with PPID have increased numbers of glucocorticoid receptors and increased 11? hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in the suspensory ligament compared to unaffected horses, suggesting a role for abnormal local cortisol metabolism.6

Some older studies posit that abnormal proteoglycan deposition and turnover is the primary cause of the functional and structural changes.4,7,10 Affected horses have an atypical isoform of the proteoglycan decorin,7 and affected ligaments have markedly increased amounts of the proteoglycan aggrecan, as well as increased amounts of aggrecan degradation products and enzymes.10 One report suggested that abnormal proteoglycan accumulation may be systemic in affected horses,4 but the findings could not be reproduced.11 The cause of the altered proteoglycan milieu is unknown; however, the more recent genome-wide association study failed to identify any alterations in the genes responsible for proteoglycan turnover.9

Despite the lack of inflammatory cells in affected ligaments, there are increased levels of inter-alpha-trypsin-inhibitor components, which are associated with multiple inflammatory conditions.10 In addition, some of the candidate genes identified in the genome-wide association study are associated with inflammatory pathways.9 The complete role of inflammatory processes in disease progression is unknown.

Finally, true suspensory ligament desmitis with degeneration has been rarely reported in horses and donkeys as a result of onchocerciasis.2 Degenerative lesions of the ligament are similar, but they are accompanied by eosinophilic granulomas with encysted nematodes.2

Contributing Institution:

Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences, University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine https://vetmed.tennessee.edu/academics/biomedical-and-diagnostic-sciences/JPC Diagnoses:

Ligament: Degeneration, chronic, diffuse, marked, with increased ground substance, vascular proliferation, loss of ligamentocytes, and cartilaginous metaplasia.JPC Comment:

The JPC's own LTC Erica Barkei moderated this week?s conference and chose a variety of fascinating entities, three of which that have never been seen before in the Wednesday Slide Conference (WSC). She tends to look specifically for cases that are either novel to the WSC, are within residents 5-year reading windows, or will stimulate great discussion amongst participants. She was certainly successful in that mission this year!This case, coupled with a well-written and thorough comment from the contributor on this challenging clinical condition, gifted participants with a beautiful slide of an oft-forgotten organ (tendon/ligament) with all the classic features of suspensory ligament degeneration (SLD). The WSC team is grateful to the contributor for this case and the excellent educational value it brought to the conference.

Conference discussion focused on the proposed pathogeneses of this condition (genetic vs. metabolic vs. athletic) in horses and its likely multifactorial origins (see contributor comment). A key feature of SLD/DSLD is acellular accumulation of proteoglycans, including decorin and aggrecan, replacing cells and collagen bundles.10 This suggests a disturbance to matrix homeostasis where the responses of the matrix to mechanical loading are disrupted. As the contributor stated in their comment, there have been numerous genes found to be associated with SLD/DSLD, including those involved in tendon aging (PIN1), mechanotransduction (KANK1, KANK2, JUNB, SEMA7A), collagen synthesis (COL4A1, COL5A2, COL5A3, COL6A5), matrix response to hypoxia (PRDX2), and lipid metabolism (LDLR, VLDLR).8,9 These features parallel the changes seen in humans with similar tendinopathies. There are currently conflicting articles within the literature on if the proteoglycan accumulation seen in SLD is systemic or localized, and more research is needed to determine this.4,11

There were a few important buzzwords or phrases mentioned during conference that are important to include in a histologic description of an SLD case and include some form of ?collagen fiber disorganization and loss of tenocytes/ligamentocytes. (If anyone is wondering, What the heck are tenocytes and ligamentocytes?, they are, quite simply, fibroblasts respectively within a tendon or ligament.) The different types of collagens within tendons and ligaments were also reviewed and include: Type I collagen, which is the most prevalent within the normal flexor tendons; Type II collagen, which is found within enthesis insertions and areas where a tendon changes directions around a bony prominence; and, lastly, type III collagen, which is one of the first collagens synthesized within tendons at sites of injury.

The major histologic findings within ligaments suffering from SLD include loss of longitudinal arrangement of collagen fibers (disorganization), proteoglycan accumulation (increased ground substance), presence of chondrocytes (chondroid metaplasia), hemorrhage, vascular proliferation, widened interstitial connective tissue septae, and a lack of inflammatory cells.8 As this disease develops, regardless of cause, degenerating collagen fascicles blend together and there is either death of the tenocytes/ligamentocytes or metaplasia of tenocytes/ligamentocytes into chondrocytes. Fibrosis develops within and around the ligament and is usually associated with hypertrophied tenocytes/ligamentocytes. These areas are generally interpreted as failed attempts at repair.

As these changes progress, the suspensory ligament (SL) progressively thickens, weakens, and ultimately ruptures, resulting in the classic dropped fetlocks seen in affected horses.8,9 Some horses may also have neurogenic muscular atrophy secondary to either nerve entrapment within areas of fibrosis or due to nerve compression from a thickened and enlarged SL. SLD is typically more evident in the pelvic limbs and is usually bilateral, although some horses have all four limbs affected.3,8,9

The last major discussion point in conference related to the use of the term desmitis vs. degeneration. In a true SLD/DSLD case, there should be no inflammatory cells within the tendon/ligament, so conference participants favored degeneration over desmitis. The exception to this would be in cases of ligamentous Onchocerciasis, where an eosinophilic and granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate could be expected.2 In addition to morphing degeneration for this case, a few withs were added to the JPC morph to better define the typical findings associated with the degeneration in a case of SLD. Participants thought it was academically pertinent to ensure those were part of the morph for the purposes of resident education and encompass the primary histologic changes of this condition.

References:

- Batisse M, Somda F, Delorme JP, Desbiez F, Thieblot P, Tauveron I. Spontaneous rupture of Achilles tendon and Cushing's disease. Case report. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2008;69:530-531.

- Brown KA, Johnson AL, Bender SJ, et al. (2023). Onchocerca sp. in an imported Zangersheide gelding causing suspensory ligament desmitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2023;37:735-739.

- Dyson S. Clinical commentary: Is degenerative change within hindlimb suspensory ligaments a prelude to all types of injury? Equine Vet. Educ. 2010;22(6):271-274.

- Halper J, Kim B, Khan A, Yoon JH, Mueller POE. Degenerative suspensory ligament desmitis as a systemic disorder characterized by proteoglycan accumulation. BMC Vet Res. April 12, 2006.

- Hofberger S, Gauff F, Licka T. Suspensory ligament degeneration associated with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction in horses. Vet J. 2015;203:348?350.

- Hofberger S, Gauff F, Thaller D, Morgan R, Keen J, Licka T. Assessment of tissue-specific cortisol activity with regard to degeneration of the suspensory ligaments in horses with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction. Am J Vet Res. 2018;79(2):199?210.

- Kim B, Yoon JH, Zhang J, Mueller POE, Halper, J. Glycan profiling of a defect in decorin glycosylation in equine systemic proteoglycan accumulation, a potential model of progeroid form of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;501:221?231.

- Mero J, Pool RR. Twenty cases of degenerative suspensory ligament desmitis in Peruvian Paso horses. AAEP Proceedings. 2002;48:329-334.

- Momen M, Brounts SH, Binversie EE, et al. Selection signature analyses and genome-wide association reveal genomic hotspot regions that reflect differences between breeds of horse with contrasting risk of degenerative suspensory ligament desmitis. G3-Genes Genom Genet. 2022;12(10).

- Plaas A, Sandy JD, Liu H, et al. Biochemical identification and immunolocalization of aggrecan, ADAMTS5 and inter-alpha-trypsin-inhibitor in equine degenerative suspensory ligament desmitis. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(6): 900?906.

- Schenkman, Daniel et al. Systemic proteoglycan deposition is not a characteristic of equine degenerative suspensory ligament desmitis (DSLD). J Equine Vet Sci. 2009;29(10): 748?752.