Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 4, Case 4

Signalment:

8 years old, female, Correlophus ciliatus (formerly Rhacodactylus ciliatus), crested gecko

History:

The gecko was lethargic and sitting on the floor of the terrarium for prolonged periods instead of its normal climbing activity on the terrarium’s vegetation. The owner noticed cutaneous ulcers on the gecko, which the owner treated topically. The gecko was found dead two days after clinical signs started.

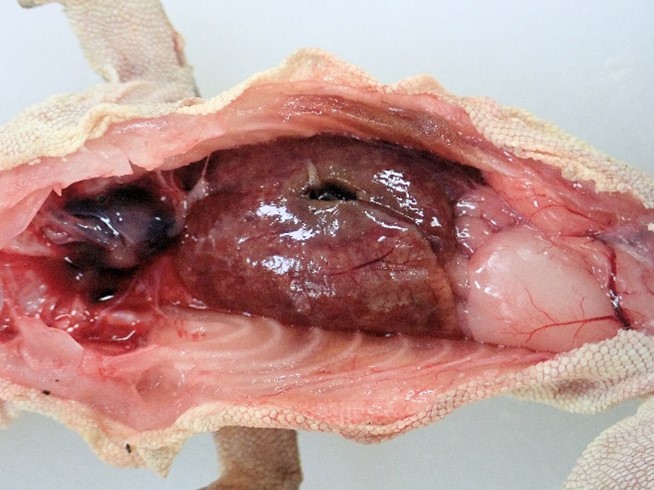

Gross Pathology:

The carcass presented for postmortem examination was an 8 years old, 31.5 grams, female, crested gecko. The gecko was slightly underweight (normal weight of an adult female crested gecko is 35-55 grams) with moderate amounts of fat in the coelomic fat pads. The subcutis and organs were dry and tacky suggesting dehydration. The liver was markedly enlarged, pale, firm and contained numerous coalescing variably sized tan foci (Figure 1).

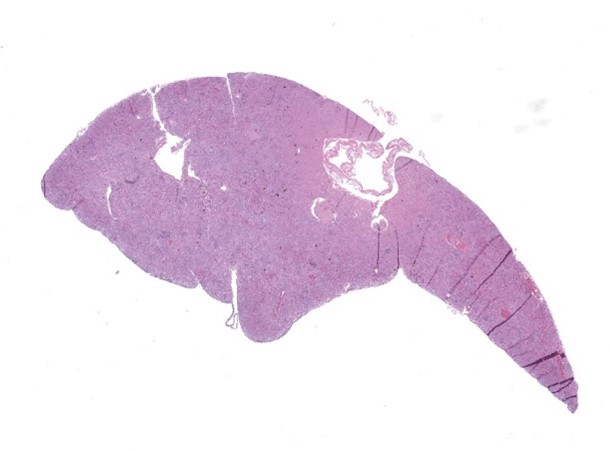

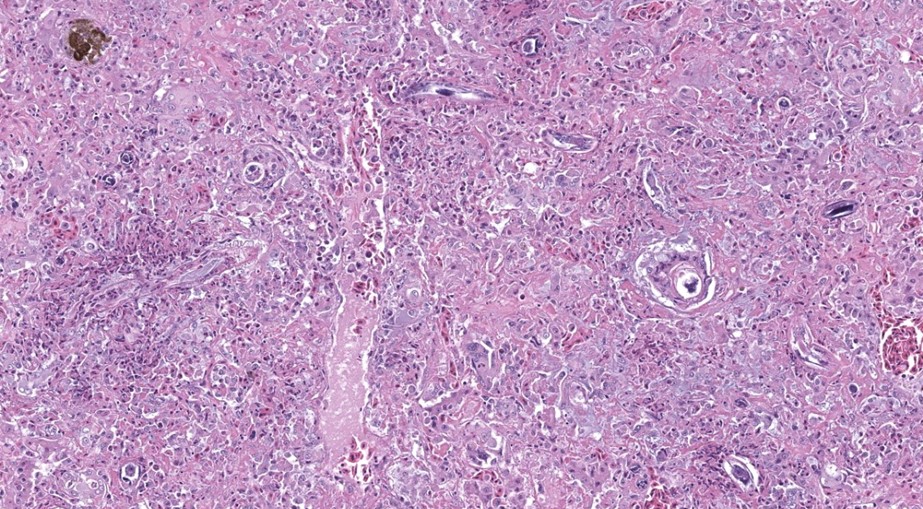

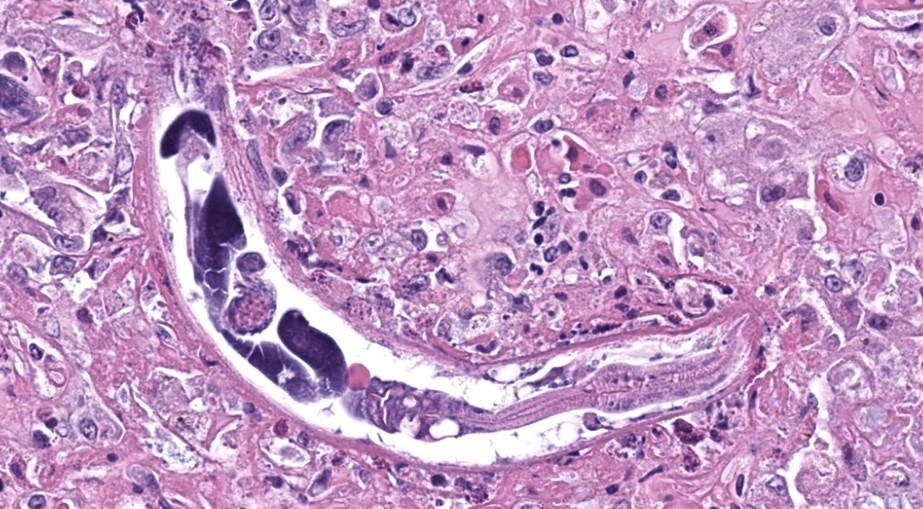

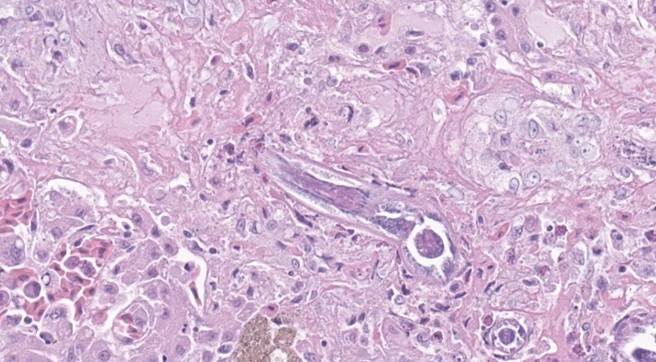

Microscopic Description:

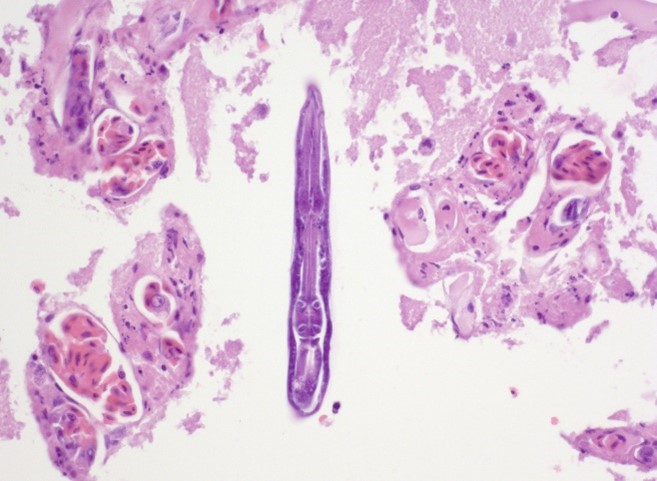

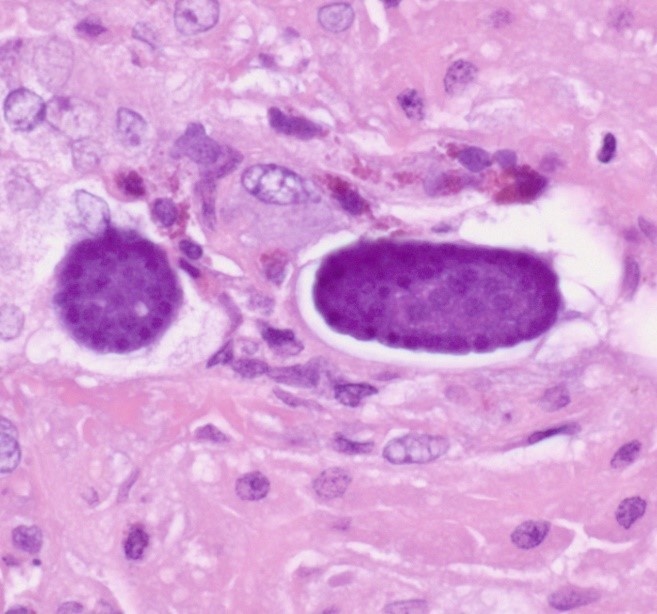

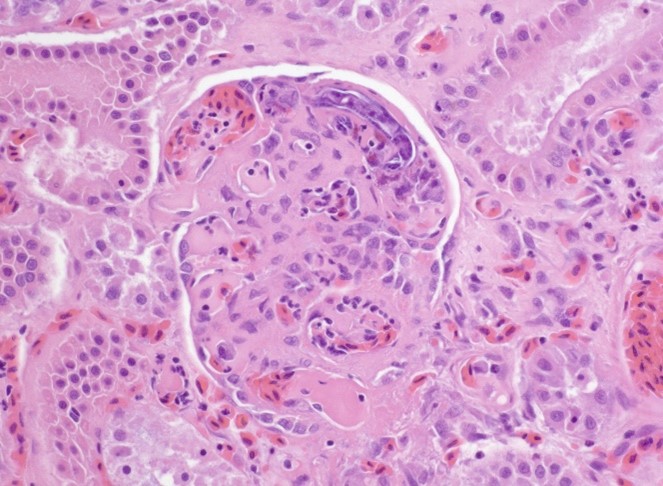

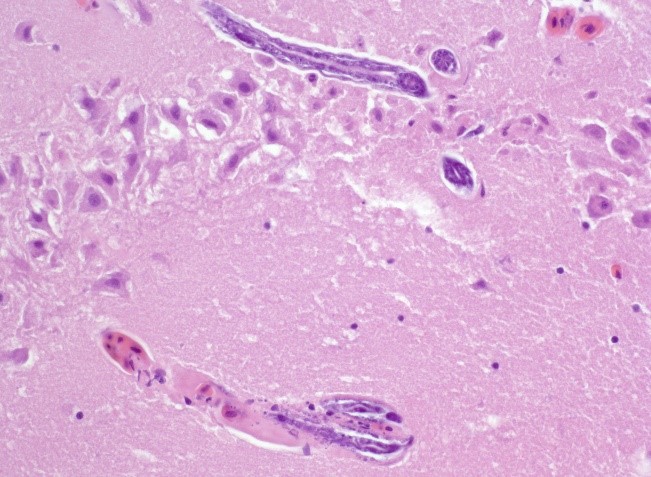

The liver contained numerous small adult and larval rhabditid nematodes that were often surrounded by variably sized coalescing foci of necrosis admixed with macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and granulocytes. A few nematodes were fragmented and mineralized. The musculature of the nematodes was indistinguishable due to their small size. The nematodes had a rhabditiform esophagus with a corpus, isthmus and bulb (Figure 2). They had a single intestine and a paired genital tract (Figure 3). The genital tract contained large uninucleate ova as well as multinucleated ova (Figure 4). There were rare free multinucleated ova within the hepatic parenchyma (Figure 5). There was bile duct hyperplasia in the portal areas that were within the affected foci. The capsule was multifocally mineralized. In addition to the liver, rhabditid nematodes could be seen intravascular and within the parenchyma of the kidney (Figure 6), lung (Figure 7), brain (Figure 8), intestine, spleen, pancreas and ovary. These organs were not submitted.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, granulocytic and granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing with intralesional adult and larval rhabditid nematodes most consistent with Strongyloides species.

Contributor’s Comment:

Endoparasitism is a frequent disorder of reptiles.2,18 They are host to a large number of parasites including protozoa, trematodes, cestodes, nematodes, acanthocephalans, and pentastomes.2,7,11,12,18 The most common two genera of rhabditiform nematodes to infect reptiles are Rhabdias and Strongyloides .12,18 Rhabdias species are pulmonary parasites of anurans and reptiles.1,12, 18 Entomelas species are rhabditid parasites of the lungs of some species of lizards.18 Strongyloides are intestinal parasites of a large number of vertebrate species including mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians.1,12,14,16,17 Rhabdias species can be identified histopathologically by their intestine that has pigmented intestinal cells, vacuolated lateral chords, and females can have larvated ova in their paired uteri.5 Strongyloides species also have a paired genital tract, do not have pigmented intestinal cells, and most species lay uninucleate ova that develop in the tissue or intestine.5 The ova of Rhabdias species and Strongyloides species are embryonated in the feces of the host, and it is common to find free first stage rhabditiform larvae in the feces of infected hosts.12,18 The embryonated ova and larvae of both species in the feces of the host are morphologically similar and difficult to impossible to distinguish from one another.12,18

As stated previously, Rhabdias species are lung parasites of anurans and reptiles.1,9,12 The third stage larvae of Rhabdias species infect the host percutaneously or orally.9 Oral infection mediated by eating infected prey is most likely important in reptiles with dry and scaly skin. After penetration into the connective tissue, the parasites molt into fourth stage larvae and enter the body cavity. The worms migrate to and enter the lungs as adult where they feed on the host’s blood. The parasitic worms are female with some species reproducing by parthenogenesis or some species are hermaphrodites.1 Rhabdias species ova can be laid by the female or the embryonated ova can develop within the body cavity of the female worm being release when she dies (matricidal endotoky). Rhabdias ova passed in the feces can develop by heterogony (first stage larvae molt twice to form third stage larvae of both sexes to become adults, mate and produce ova) or homogony (first stage larvae molt twice to become filariform third stage larvae that infect the host and mature into parthenogenetic females). Infected animals can exhibit respiratory distress, which can be severe.12,18

The intestinal parasite Strongyloides species can infect numerous vertebrate hosts.1,14,16,17 The genus has been best studied in mammals. There appears to be some degree of host specificity with the different Strongyloides species, but some species like S. stercoralis can infect multiple mammalian species and have the potential to be zoonotic particularly between dogs and nonhuman primates and humans.10,14 However, molecular techniques have demonstrated that there are differences between the human and dog strains of S. stercoralis raising the question of whether the dog strains of S. stercoralis are truly zoonotic.10,14

The life cycle of Strongyloides species is similar to that of Rhabdias with one major difference; some Strongyloides species (particularly S. stercoralis, S. fuelleborni, and S. fuelleborni kellyi in humans) have the potential to autoinfect the host that can lead to infections that last decades.8,10,13,15,16,17,19 The parasitic form of Strongyloides are parthenogenetic females. The female nematodes mostly live burrowed in the mucosa of the small intestine with some exceptions notably S. tumefaciens and occasionally S. stercoralis where the females live in nodules in the colon of cats.14,19 The ova laid by the females embryonate in the mucosa and lumen of the small intestine and are passed in the feces as embryonated eggs or first stage rhabditiform larvae. The first stage rhabditiform larvae in the environment will molt twice to become third stage filariform larvae. The filariform larvae can then either penetrate the skin or mucosa of the mouth to infect the host or molt two more times to form adult free-living male and female worms. The adult free-living male and female worms can mate and their female offspring will molt to the infective filariform larvae to percutaneously or orally infect the host. Once inside the host, the filariform larvae can migrate to the small intestine or enter the vasculature where they migrate through the heart to the lungs. The filariform larvae in the lungs are coughed up and swallowed to reach the small intestine. When in the small intestine, the filariform larvae will mature into adult females. In autoinfection, the first stage rhabditiform larvae will molt twice in the large intestine to the infective third stage filariform larvae. The filariform larvae will penetrate the intestinal mucosa or perianal skin and migrate to the small intestine, which in some cases occurs through random organs. Humans and animals are initially exposed to infective filariform larvae of Strongyloides in a contaminated environment particularly in endemic areas.17 The environment (water, foodstuffs, soil, and unwashed body parts) is contaminated by feces from an infected human or animal.17 In addition, insects can mechanically carry ova of Strongyloides.17

Clinical disease caused by Strongyloides species is typically mild and self-limiting.13,14,15,16,19 It usually consists of diarrhea and respiratory disease that is most prevalent in individuals when they are initially exposed to the parasites. Naïve individuals exposed to infective filariform larvae can also develop dermatitis due to the parasites migrating through the skin. In domestic animals, disease caused by Strongyloides typically occurs in neonatal animals. In reptiles, particularly snakes, disease caused by Strongyloides can manifest as diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss and lethargy.12,18 There are, however, cases of severe disease caused by Strongyloides species that have been described in humans and rarely dogs.3,4,7,8,13,15,16 Severe disease caused by Strongyloides has been divided into two syndromes termed hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease, but some consider the syndromes to be the same.8,13,15,16 Hyperinfection syndrome can occur in any infected individual, but is most often seen in immunocompromised individuals. Disseminated disease occurs in immunocompromised individuals. Both of these syndromes are often fatal. Hyperinfection syndrome is defined as a severe infection with Strongyloides nematodes in the normal locations of the parasites: the skin, the intestine, and the lungs. The time of completion of the life cycle of Strongyloides in hyperinfections is shortened. Disseminated strongyloidiasis occurs when Strongyloides parasites are found in organs outside of the normal life cycle (i.e., organs other than the skin, intestine or lungs). The gecko in this case most likely had disseminated strongyloidiasis.

Contributing Institution:

New Mexico Department of Agriculture Veterinary Diagnostic Services

www.nmda.nmsu.edu/vds

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing and granulomatous, chronic, diffuse, marked, with intraparenchymal rhabditoid adults, larvae, and eggs.

JPC Comment:

This conference concludes with a wonderful parasite case. We previously showed this slide to Dr. Chris Gardiner who confirmed the features of this nematode in histologic section and remarked that he had never seen a case like this one in over 50 years as a parasitologist! The presence of Strongyloides within the liver is unusual as they are typically encountered within the epithelial layer of the enteron, or less commonly, within the mucosa of the urinary bladder or the skin and lungs as the contributor notes.

Conference participants were able to appreciate most of the major features of adult and larval rhabditid nematodes. Careful examination of the slide is required to identify the few eggs scattered within the parenchyma.

Finally, we commend the contributor for their exhaustive discussion of Strongyloides. We have little to add on save for mentioning a recent Veterinary Pathology article concerning proliferative strongyloidiasis in a colony of colubrid snakes.6 The histologic features of Strongyloides in these snakes was similar to the conference case, aberrant migration to the reproductive, respiratory and upper alimentary tracts, as well as the eye.6 These findings in this paper highlight the utility of speciating the Strongyloides via molecular techniques to characterize novel species in the face of unexpected tissue distribution.

References:

- Anderson RC. Nematode transmission patterns. J Parasitol. 1988;74(1):30-45.

- Benson KG. Reptilian gastrointestinal diseases. Semin Avian Exot Pet Med. 1999;8(2):90-91.

- Cervone M, Giannelli A, Otranto D, Perrucci. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in an immunosuppressed dog from France. Revue Vétérinaire Clinique. 2016;51(2):55-59.

- Dillard KJ, Saari SAM, Marjukka A. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a Finnish kennel. Acta Vet Scand. 2007;49,37.

- Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. Rhabditoids. In: An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2006.

- Graham EA, Los Kamp EW, Thompson NM, et al. Proliferative strongyloidiasis in a colony of colubrid snakes. Veterinary Pathology. 2024;61(1):109-118.

- Graham JA, Sato M, Moore AR, et al. Disseminated Strongyloids stercoralis infection in a dog following long-term treatment with budesonide. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2015;254(8):974-978.

- Ippen R, Zwart P. Infectious and parasitic diseases of captive reptiles and amphibians with special emphasis on husbandry practices which prevent or promote diseases. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epiz. 1996;15(1):43-54.

- Kassalik M, Mönkem?ller K. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7(11): 766-768.

- Langford GJ, Janovy Jr. J. Comparative life cycles and life histories of North American Rhabdias spp. (Nematoda: Rhabdiasidae): lungworms from snakes and anurans. J Parasitol. 2009;95(5):1145-1155.

- Page W, Judd JA, Bradbury RS. The unique life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis and implications for public health action. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018; 3(2), 53;

- Ratai AV, Lindtner-Knific R, Vlahovi? K, et al. Parasites in pet reptiles. Acta Vet Scand. 2011;53,33.

- Šlapeta J, Modrý D, Johnson R. Reptile parasitology in health and disease. In: Doneley B, Monks D, Johnson R, Carmel B, eds. Reptile Medicine and Surgery in Clinical Practice. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2018.

- Tefé-Silva C, Machado ER, Faccioli LH, Ramos SG. Hyperinfection syndrome in strongyloidiasis. In: Rodriquez-Morales AJ, ed. Current Topics in Tropical Medicine. InTech; 2019.

- Thamsborg SM, Ketzis J, Horii Y, Matthews JB. Strongyloides spp. infections of veterinary importance. Parasitol. 2017;144:274-284.

- Vasquez-Rios G, Pineda-Reyes R, Pineda-Reyes J, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome: a deeper understanding of a neglected disease. J Parasit Dis. 2019;43(2):167-175.

- Viney ME, Lok JB. Strongyloides spp. In: WormBook. 1-15; doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.141.1.

- White MAF, Whiley H, Ross KE. A review of Strongyloides spp. environmental sources worldwide. Pathogens. 2019;8,91; doi:10.3390/pathogens803009.

- Wilson SC, Carpenter JW. Endoparasitic diseases of reptiles. Semin Avian Exot Pet Med. 1996;5(2):64-74.

- Wulcan JM, Dennis MM, Ketzis JK, et al. Strongyloides spp. in cats: a review of the literature and the first report of zoonotic Strongyloides stercoralis in colonic epithelial nodular hyperplasia in cats. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12,349.