Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 2

September 5th, 2018

CASE II: 13V1542 (JPC 4034956).

Signalment: 1 year old, female, Hereford heifer

History: Tissue samples sent in formalin from a post-mortem done by the referring veterinarian from Victoria, Australia, in March 2013 with the following history. 14 months old Hereford heifers in good condition in high country on lush green pasture. Vaccination program and management good and properly done. 1 x died 6 days ago. Lost 6 last year from this paddock. Dead on arrival. Showed ataxia before died.

Gross Pathology: Submitted by referring veterinarian. Petechiae through omentum. Abomasum petechiae and filled with brownish blood-tinged fluid. Petechiae and ecchimoses on pericardium, epicardium and endocardium.

Laboratory results: None.

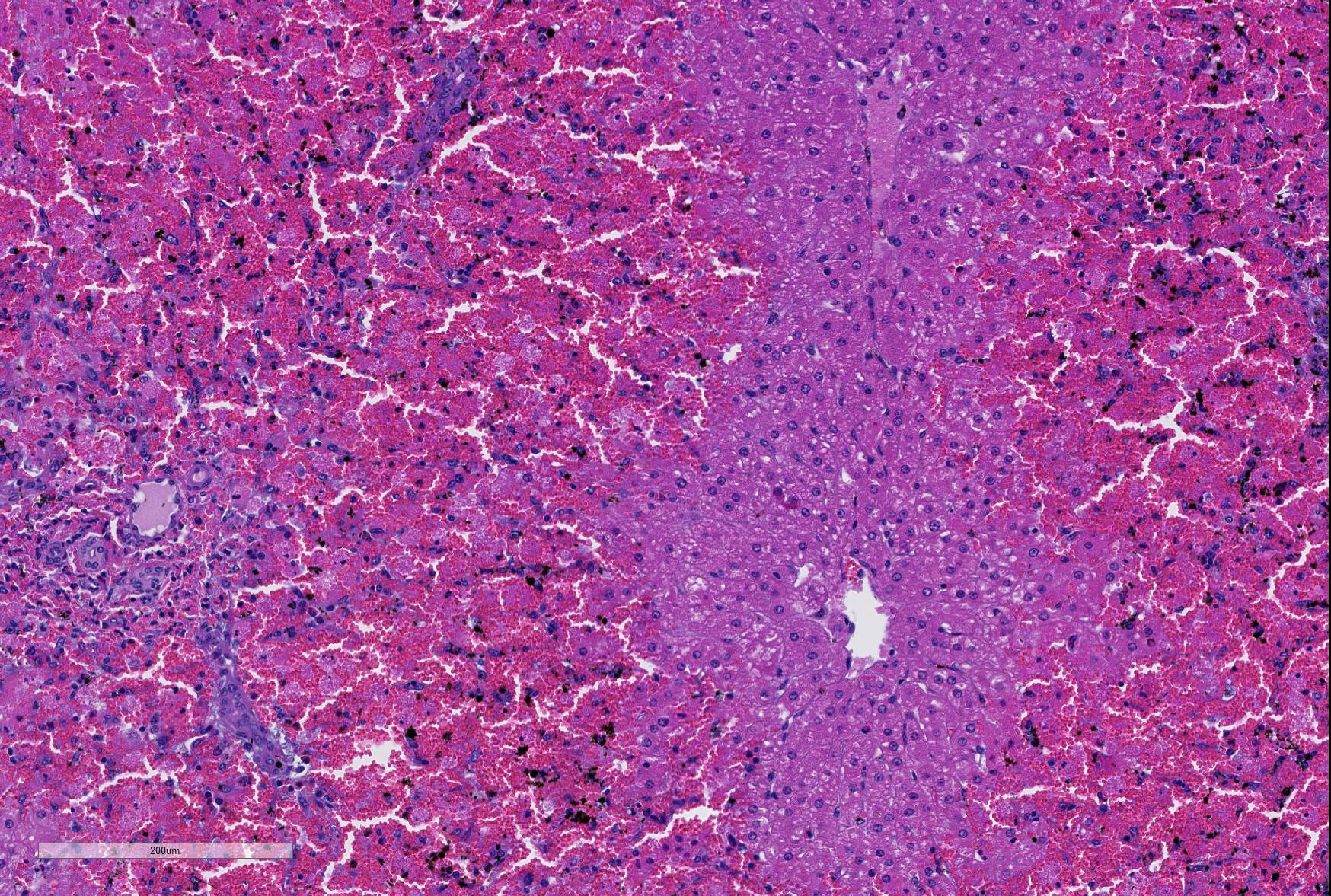

Microscopic Description: Liver; severe periportal hepatocellular necrosis extended throughout all liver sections examined and involved up to 50% of the hepatocytes in each lobe. The degenerate hepatocytes had been replaced with blood and neutrophils. Portal areas contained moderate biliary hyperplasia and mild neutrophil infiltration.

An unidentified artifact similar to acid hematin was present throughout all sections.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses: Liver; severe acute disseminated periportal hepatocellular necrosis, moderate biliary hyperplasia and moderate neutrophilic hepatitis.

Contributor’s Comment: The hepatic lesion is very severe and sufficient to explain the sudden death of the heifer. Periportal hepatocellular necrosis is a relatively rare lesion in cattle and is typical of ABLD (acute bovine liver disease). ABLD typically strikes in autumn in the south eastern areas of Victoria, Australia and affects dairy and beef cattle. Clinical signs of the disease include decreased milk yield and sudden death with photosensitization developing in survivors. The cause is presumed toxic but the agent has never been defined.

It has been associated with rough dog’s tail grass (Cynosurus echinatus), but no toxic agent has been found in this grass. The known phytopathogenic fungus Drechslera biseptata has been isolated from C. echinatus collected at the time of, and from the sites of, outbreaks of ABLD and is tentatively associated with its pathogenesis1. Whether there are other hepatotoxins involved is not known. An attempt to reproduce the disease in cattle by feeding Cynosurus echinatus mixed with an inoculum of Drechslera biseptata grown from an isolate taken from a previous outbreak of ABLD was not successful2.

The petechiation described in the history is also a common PM change of this condition. The slides contained an artifact similar to acid hematin but could not be removed with the usual laboratory treatment for acid hematin. The artifact was not identified.

JPC Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatocellular necrosis, periportal to midzonal, diffuse, with hemorrhage.

Conference Comment: Although there is current heightened sensitivity among cattle producers in Australia and New Zealand to the clinical effects and implications of acute bovine liver disease, intensive research into its pathogenesis has not yet been published. An excellent review by Reed et al.4 was published subsequent to the submission of this case and is summarized below.

Acute bovine liver disease (ABLD) commonly formerly known as phytotoxic hepatitis, affects grazing beef and dairy cattle regardless of age, sex or breed. Clinical signs consistently include an initial drop in milk production, photosensitization, an altered behavior such as seeking shade on overcast days. Depression, pyrexia, appetite loss, and agitation may be observed in some cattle, and acute cases may result in death prior to display of clinical signs. Serum biochemistries are nonspecific, including marked elevation of aspartate transaminase, glutamate dehydrogenase, and moderate increases in gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase activity. Histologic features of acute disease are as seen in this slide, with periportal necrosis as a characteristic feature. The pathology seen in chronic cases has yet to be described.4

The nonspecific signs and lesions as well as the sporadic and unpredictable nature of deaths with this condition complicate the investigation of ABLD occurrences. Outbreaks often occur on pastures which contains senescent rough dog’s tail grass (Cynosurus echinatus), however this plant is found worldwide and does not appear to cause illness on its own. Feeding trials with this plant have demonstrated no ill effects in several studies.

Because of the similarity of the epidemology of ABLD to other mycotoxicoses, fungal infections of rough dog’s tail grass are suspected. The most common fungal species identified in ABLD occurrences include Colletotrichum graminicola and Drechslera sp. aff siccans, with D. biseptata and Colleotrichum sp. aff. coccodes were also identified less commonly. As Colletotrichum sp., has not been reported to produce mycotoxins, leaving Dreschlera as the more likely candidate. Aslani et al.1 identified in vivo hepatotoxicity from extracts of the spores and mycelia of D biseptata who’s mass spectral profile implies a cytochalasin-like activity in rat hepatocytes in vivo. This research also demonstrated a lower level of toxicity from spores alone as compared to extracts from mycelia, or mycelia and spores combined.

As most ABLD occurrences occur in the autumn, current thought is that weather change may stimulate production of fungal toxins or toxic spores in infected grasses. Cattle producers are recommended to be vigilant for signs of disease in this time of the year when cattle are grazing high risk pasture. Additionally, sheep may be used to graze out a high risk pasture, as they do not appear to be susceptible, or at least less susceptible to the effects of the putative toxin.

Periportal hepatocellular necrosis is an uncommon pattern of hepatocellular injury caused by a limited subset of toxins in veterinary medicine.2 The majority of these toxins may not require metabolism by the mixed function oxidases of centrilobular hepatocytes, and simply overwhelm the initial hepatocytes they encounter as they enter the liver from the portal venous circulation. Other toxins may simply require metabolism by the limited amounts of biotransforming enzymes enzymes present within periportal hepatocytes to exert their effect. Additionally, periportal necrosis may be seen in toxins that are excreted in the bile, and there are damage is enhanced by cholestatic disease. Toxins which have been identified in veterinarian medicine as characteristically resulting in periportal necrosis include elemental phosphorus, allyl alcohol, and boobialla (Myoporum tetandrum) another toxic plant found in Australia which contains furanoid sesquiterpene oils as the toxic principle.1

The lack of traditional descriptors for chronicity and severity is a consequence of the choice of the term “necrosis” as the main feature of this slide. As necrosis is neither acute or chronic, nor are there levels of severity of necrosis, we generally do not use these terms as modifiers. An estimation of extent of necrosis is probably more appropriate than “severity” in these cases, and diffuse gives an excellent picture of the extent of necrosis seen here, with all periportal hepatocytes in the section being necrotic.

Contributing Institution:

Gribbles Veterinary Pathology

1868 Dandenong Rd,

Clayton VIC 3168

Australia

References:

1. Aslani, Pascoe, Kowalski, Michalewicz, Retallick and Colegate. In vitro detection of hepatocytotoxic metabolites from Drechslera biseptata: a contributing factor to acute bovine liver disease? Aust J Experimental Agriculture. 2006; 46: 599–604.

2. Brown DL, Van Wettere AJ, Cullen JM. Hepatobilary system and exocrine pancreas. In: Zachary, J, ed, 6 Ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. Elsevier, St. Louis MO, 2017, p. 423.

3. Lancaster, Jubb and Pascoe. Lack of toxicity of rough dog’s tail grass (Cynosurus echinatus) and the fungus Drechslera biseptata for cattle. Vet J. 84 (3):98-100.

4. Read E, Edwards J, Deseo M, Rawlin, G, Rochfort, S. Current understanding of acute bovine liver disease in Australia. Toxins 2017; 9(8)