Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2011-2012

Conference 25

16 May 2012

CASE I: N315/07 (JPC 3126927).

Signalment: Four-year-old female Belgian blue cross-breed, bovine (Bos taurus). History: Access to âroughâ grazing. Presented with stranguria and hematuria.

Gross Pathology: Ammoniacal smell on opening the peritoneal cavity in which a diffuse fibrin-rich exudate and approximately 60 liters of urine-containing fluid is present. There is perforation of the bladder wall approximately 4cm proximal to the urethral exit within an approximately 16cm diameter, soft red mass raised above the mucosal surface. A similar lesion extends along the ventral bladder wall towards the ureteral openings. The distal 30cm long segment of the esophagus is diffusely mottled red and pale with longitudinal sloughing of the mucosa (consistent with persistent reflux resulting in extensive erosion/ulceration).

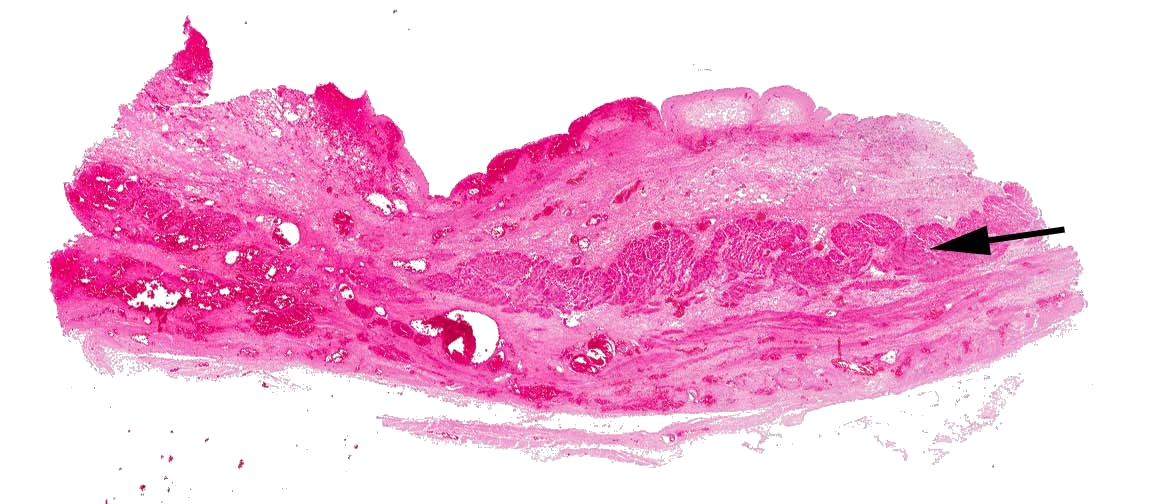

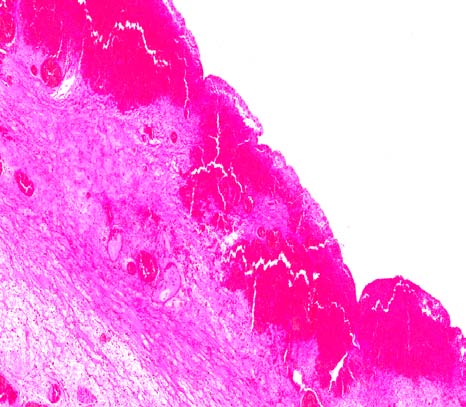

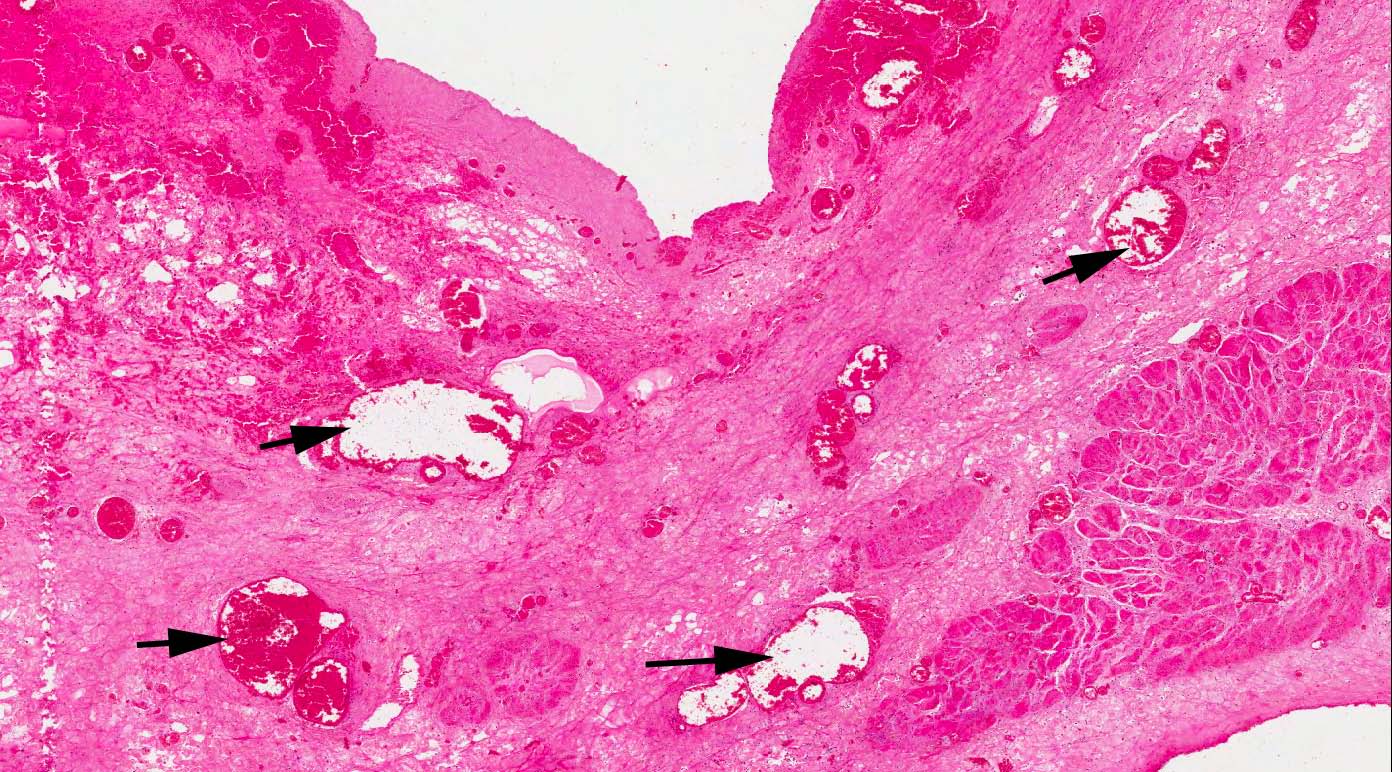

Contributorâs Microscopic Description: Sloughing of urothelium with an irregularly elevated exposed stromal surface containing abundant engorged, ectatic blood vessels of varying diameter lined by well-differentiated endothelial cells with adjacent stromal hemorrhage, fibrinous exudate and scattered leukocytes. These changes extend transmurally with evidence of vasculitis & thrombosis. Fibrinocellular exudate was noted on the serosal surface of the intestine (peritonitis).

Contributorâs Morphologic Diagnosis: Bladder: Vascular congestion, ectasia, and hemorrhage, with attendant vasculitis, thrombosis and fibrinous exudation; diffuse; severe.

Contributorâs Comment: The gross and histopathological changes in the bladder are consistent with bladder perforation and peritonitis secondary to hemangiomatous lesions in the bladder wall. Such lesions are associated with the long-term ingestion of bracken fern in cattle (Enzootic hematuria). This animal had been on rough grazing with access to such fern.

Enzootic hematuria occurs in mature cattle, is characterized by hematuria and anemia, and is associated with hemorrhages or neoplasms particularly of the bladder. The syndrome is attributed to the long-term ingestion of bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum subsp. aquilinum) and can be reproduced experimentally.3,5 Bracken fern contains several toxins including a thiaminase, carcinogens (quercetin, shikimic acid, prunasin, ptaquiloside, ptaquiloside Z, aquilide A), and a Cattle fed low levels of bracken fern develop microscopic, followed by macroscopic, hematuria. Microhematuria is usually associated with petechial or ecchymotic hemorrhages of the bladder mucosa with microscopic evidence of vascular ectasia and engorgement and these vessels are prone to hemorrhage. Nodular hemangiomatous lesions also develop.3 Occasionally, macroscopic hematuria is associated with these non-neoplastic changes, but usually results from the development of tumors which ulcerate and hemorrhage into the bladder lumen.3 Several types of epithelial and mesenchymal neoplasms may develop, and in over 50% of affected cattle, mixed epithelialâmesenchymal neoplasms develop. Papillomas, fibromas, and hemangiomas with carcinomas are most commonly found.1,3,5

JPC Diagnosis: Urinary bladder: Necrosis, transmural, diffuse, with marked hemorrhage, vascular ectasia, and necrotizing vasculitis.

Conference Comment: Conference participants discussed obstruction as a likely and more commonly encountered candidate condition for the lesion in this case, and possibly the cause of the histologic lesion. The expected neoplasia with hemorrhagic cystitis was not visible in the slide, and the grossly described masses may have caused an obstruction and the subsequent transmural hemorrhage and necrosis of the bladder wall, leading to the rupture.

This cow likely then had post-renal azotemia, and although serum was not available for analysis, conference participants considered the option of measuring the aqueous humor of the eye at necropsy to determine if the animal was azotemic, since creatinine is not protein-bound and diffuses freely in both the eye and the abdominal fluid. The urea nitrogen and creatinine of the abdominal fluid could be compared to that of the aqueous humor, and in the case of a ruptured urinary bladder, the concentrations in the abdominal fluid should approach double that of the serum or humor.2,4

Additional clinical pathology abnormalities expected in a cow with post-renal azotemia would be hyperphosphatemia, since azotemia is the primary cause of elevated phosphorous in veterinary medicine due to decreased excretion from decreased glomerular filtration rate, and hyponatremia and hypochloremia due to loss in the urine and diffusion along the concentration gradient. Although small animals often have metabolic acidosis associated with renal failure, cattle present with metabolic alkalosis due to rumen atony and subsequent acid sequestration. This is due to stasis of ruminal content, similar to that seen in cattle with displaced abomasum or ileus. Conference participants expected a high plasma total CO2 and total bicarbonate (HCO3-) and respiratory compensation indicated by a high pCO2. Although hyperkalemia is expected with post-renal azotemia, the accompanying metabolic alkalosis in cattle drives potassium into cells in exchange for hydrogen following its concentration gradient to the extracellular space. An expected gross finding in this case would be bilateral hydronephrosis or hydroureter secondary to the obstruction.2,3,4

Contributor: UCD Veterinary Sciences Centre References:

1. Hopkins NCG. Aetiology of enzootic haematuria. Vet Rec. 1986;118:715â717.

2. Langston C. Acute uremia. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 7th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:1969-83.

3. Maxie MG, Newman SJ. The urinary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmerâs Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2007:518-520.

4. Tripathi NK, Gregory CR, Latimer KS. Urinary system. In: Latimer KS, ed. Duncan and Prasseâs Veterinary Laboratory Medicine: Clinical Pathology. 5th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011:270-80.

5. Xu LR: Bracken poisoning and enzootic haematuria in cattle in China. Res Vet Sci. 1992;53:116â121.

bleeding factor<1>.1 Administration of ptaquiloside to guinea pigs results in hemorrhagic cystitis suggesting that this is a significant toxin in the induction of hematuria.5

UCD School of Agriculture, Food Science and Veterinary Medicine

University College Dublin

Belfield

Dublin 4, Ireland

www.ucd.ie

2. Langston C. Acute uremia. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 7th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:1969-83.

3. Maxie MG, Newman SJ. The urinary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2007:518-520.

4. Tripathi NK, Gregory CR, Latimer KS. Urinary system. In: Latimer KS, ed. Duncan and Prasse’s Veterinary Laboratory Medicine: Clinical Pathology. 5th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011:270-80.

5. Xu LR: Bracken poisoning and enzootic haematuria in cattle in China. Res Vet Sci. 1992;53:116â121.

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References: