Signalment:

Gross Description:

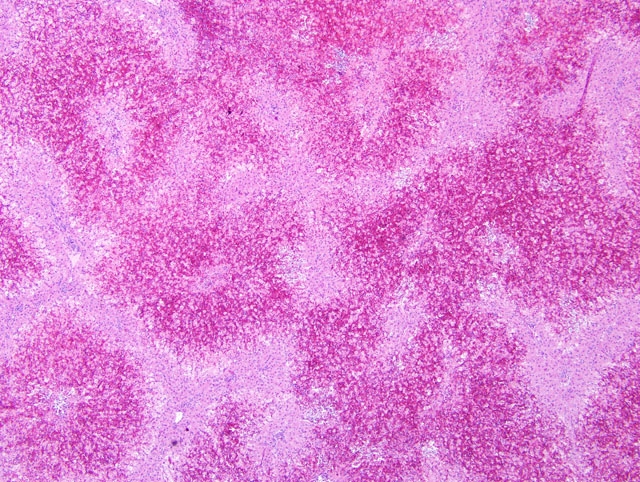

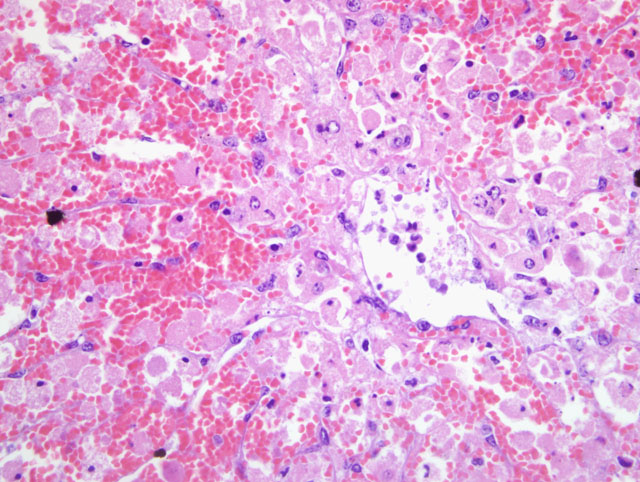

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

After ingestion of water contaminated with MCLR, the toxin is rapidly taken up in hepatocytes by carrier-mediated transport. Within the hepatocytes, MCLR inhibits protein phosphorylases 1 and 2A, which regulate cellular structural proteins. Inhibition of phosphorylases 1 and 2A promotes hyperphosphorylation of cytoskeletal proteins. Hepatocyte and endothelial cytoskeletal actin filaments distort and collapse, causing cellular structure alteration, detachment from adjoining hepatocytes and membrane instability.(1,2)

In early stages, periacinar to massive hepatic necrosis is represented by the detachment and rounding up of the altered hepatocytes and endothelial cells, extrusion of blood into the disrupted sinuses, with blood and necrotic, fully detached hepatocytes flowing into the central venous network. Hypovolemic shock due to hepatic hemorrhage usually causes death, although hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia from fulminant cessation of hepatic function can also be terminal events.(3) In cumulative low doses, liver failure, chronic inflammation and bilirubinemia can result in mortality.(3) If the animal survives the initial episode of hepatic damage, leukocytic inflammation within the periacinar necrosis proceeds to postnecrotic scarring, periacinar fibrosis, and irregular areas of parenchymal regeneration.(4)

Microcystin LR was detected in the rumen contents from this heifer, and additional heifers that died following exposure. Acute hepatic necrosis with hemorrhage was featured in the early cases that were submitted, and heifers that survived and later died exhibited subacute microscopic lesions. This incident occurred during late summer in Northern California, and site visits to the pasture where the affected heifers were housed found one water source that was a shallow, warm pond with brackish water and blue-green algae growth.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

This case was also studied in consultation with the AFIP Department of Hepatic Pathology; their differential diagnosis for the histologic lesions was broad, and included viral infection, severe ischemia, metabolic disease, and acute autoimmune hepatitis, but a toxic etiology was favored. As detailed in the conference proceedings for WSC 2009-2010, Conference 16, case III, numerous plant toxins some of which are summarized in a table therein preferentially target centrilobular hepatocytes because of the extraordinary vulnerability of this cell population to hypoxia and their relatively high concentration of cytochromes P450. Therefore, the recognition of a centrilobular to midzonal distribution of hepatocellular necrosis, while essential to the development of an inclusive differential diagnosis, is not sufficient to definitively implicate a particular plant toxin. Additional evidence is required, and in this case, prominent hepatocellular dissociation is a key clue to prompt further investigation of MCLR as a possible etiology. Reiterating the importance of ancillary diagnostic tests, particularly in cases of suspected toxicosis, the detection of MCLR in ruminal and cecal contents by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry solidifies the diagnosis in this case. The contributor provides an edifying review of the entity.

References:

2. Billiam M, Mukhi S, Tang L, Gao W, Wang JS: Toxic response indicators of microcystin-LR in F344 rats following a single-dose treatment. Toxicon 51:1068-1080, 2008

3. Briand JF, Jacquet S, Bernard C, Humbert JF: Health hazards for terrestrial vertebrates from toxic cyanobacteria in surface water ecosystems. Vet Res 34:361-377, 2003

4. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA: Liver and biliary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, p. 327. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007