Signalment:

Gross Description:

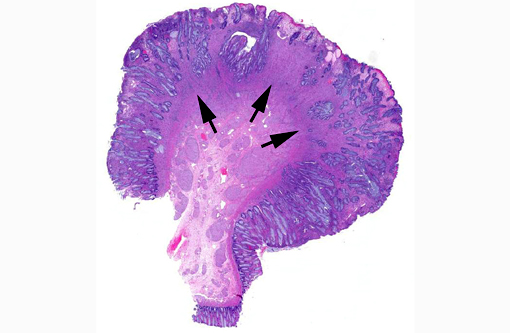

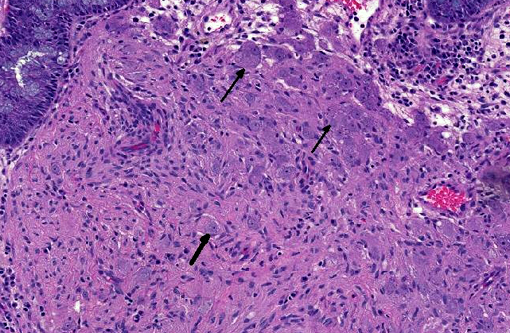

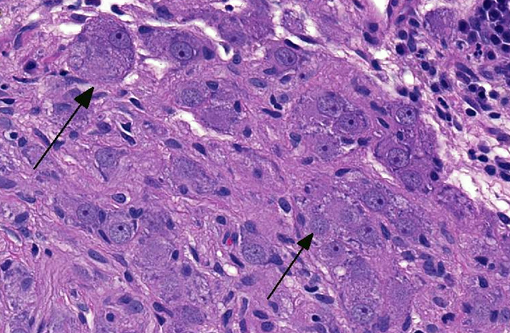

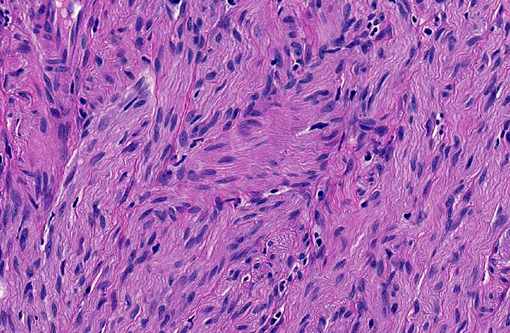

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

GN is a rare disorder characterized by the abnormal, intramural to transmural, multinodular to diffuse, proliferation of nerve fibers and ganglion cells in a segment of the intestine.(1,12) The affected segment of bowel is thickened and the lumen can be dilated or narrowed. Human GN can occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract but most reported cases involve the colon and rectum.(1,12) Human GN may present as an acute gastrointestinal obstruction or motility disorder or incidentally, during investigations for other gastrointestinal diseases.(1,12) Human hereditary intestinal GN commonly occurs in association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIb (MEN-IIb), neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1; von Recklinghausen's disease) and Cowdens disease.(1,4,12) The pathogenesis of human GN remains undetermined. Surgical resection is recommended in human GN when lesions are confined to one section of the intestine.(4) When surgical resection is not an option, symptomatic management is advocated (may include one or more of the following: adjustments, laxatives or enemas, fiber supplementation and gastrointestinal motility modifiers).(4)

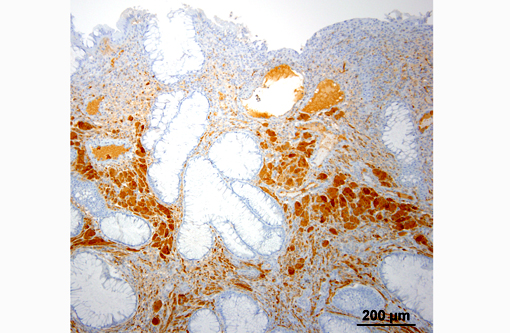

In the veterinary literature, reports of GN have been limited to juvenile and adult dogs, a horse and a steer.(3,5,9,10,12) Affected animals may present with gastrointestinal signs (e.g. vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, hematochezia, melena, tenesmus and abdominal pain) or they can be asymptomatic.(3,5,9,10,12) Abdominal ultrasonography may reveal thickening of the affected segment of the intestine and loss of the normal layers of the intestinal wall.(3,7) Histopathologic examination of full-thickness biopsies from the surgically resected affected segment of the intestine is needed to establish the diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry for neuron specific enolase, S-100 and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) will aid in establishing the diagnosis.(3,5,9,10,12) There are too few reports in the veterinary literature to comment on the prognosis or behaviour. In two of the reports the affected dogs were euthanized due to the development of a postoperative septic peritonitis.(3,5) There is a single report of a successful outcome following surgical resection in a dog with small intestinal GN.(3)

The pathogenesis of GN in animals is also unknown. It has yet to be established if the genetic mutations that have been identified in human GN occur in animal cases of GN. There is a single report in the veterinary literature in which a duplication of phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) was demonstrated, using a quantitative multiplex polymerase chain reaction, in a Great Dane puppy with concurrent colorectal hamartomatous polyposis and GN, implying a similar pathogenesis to human Cowdens disease.(3,4,12)

GN should be included as a differential diagnosis in dogs with intestinal thickening and gastrointestinal signs.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Colon: Ganglioneuroma.

2. Colon: Colitis, atrophic and lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, focal, severe.

Conference Comment:

Ganglioneuromas are characterized by exuberant proliferation of all elements of the intestinal ganglia, to include nerve fibers, ganglion cells and supporting cells.(1,7) This is in contrast to less differentiated but related tumors of ganglia origin, neuroblastomas. Neuroblastomas are composed of more primitive-appearing sheets of poorly defined cells with dark nuclei often forming pseudorosettes and lack the more mature ganglion cells of ganglioneuromas. The schwannian stroma as nicely described by the contributor and evident with immunohistochemistry for GFAP, organized fascicles of neuritic processes and fibroblasts are all histologic prerequisites for a diagnosis of ganglioneuroma.(8)

Cases may be localized to a mucosal or myenteric plexus, but are more often transmural; this case likely involves both.(1) Conference participants were reminded of the distinct locations within the intestinal wall of Auerbachs plexus (between the inner circular and outer longitudinal layers of muscularis externa) and Meissners plexus (periphery of the submucosa). They are the sites of synapsis between preganglionic and postganglionic parasympathetic nerves necessary for autonomic control of the intestinal tract.(2)

The association of ganglioneuromas and multiple tumors of all three embryologic layers in Cowden syndrome in people and their correlation with PTEN mutations lend credence to the importance of a normally functioning PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in maintaining homestasis. This tyrosine kinase pathway, initiated by the binding of growth factors, consists of a series of phosphorylation events ultimately resulting in the inhibition of apoptosis (via phosphorylation of BAD, a BCL-2 family sensor & MDM2, direct inhibitor of p53) and enhancement of cell growth and survival (via TSC1/TSC2 inactivation and subsequent mTOR activation). PTEN applies the brakes at the beginning of this cascade where it blocks phosphorylation of PIP2 into PIP3 by PI3K.(11) Correlating the PTEN mutation with ganglioneuromatosis in animals has so far been limited to a single report in one dog as previously mentioned by the contributor.(3)

References:

1. dAmore ESG, Manivel JC, Pettinato G, Neihans GA, Snover DC. Intestinal ganglioneuromatosis: mucosal and transmural types. A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of six cases. Human Pathol. 1991;22:276-286.

2. Bacha WJ, Bacha LM. Color Atlas of Veterinary Histology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:146.

3. Bemelmans I, K+â-+ry S, Albaric O, Hordeaux J, Bertrand L Nguyen F, et al. Colorectal hamartomatous polyposis and ganglioneuromatosis in a dog. Vet Path. 2011;48:1012-1015.

4. Cohen MS, Phay JE, Albinson C, DeBenedetti MK, Skinner MA. Gastrointestinal manifestations of multiple endocrine neoplasia type. Ann Surg. 2002;235:648-654.

5. Cole DE, Migaki G, Leipold HW. Colonic ganglioneuromatosis in a steer. Vet Pathol. 1990;27:461-462.

6. Fairley RA, McEntee MF. Colorectal ganglioneuromatosis in a young female dog (Lhasa Apso). Vet Pathol. 1990;27:206-207.

7. Hazell KLA, Reeves MP, Swift IM. Small intestinal ganglioneuromatosis in a dog. Austr Vet J. 2011;89:15-18.

8. Maitra A. Diseases of infancy and childhood. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010:475-476.

9. Paris JK, McCandlish AP, Schwarz T, Simpson JW, Smith SH. Small intestinal ganglioneuromatosis in a dog. J Comp Path. 2013;148:323-328.

10. Port BF, Starts RW, Payne HR, Edwards JF. Colonic ganglioneuromatosis in a horse. Vet Path. 2007;44:207-210.

11. Stricker TP, Kumar V. Neoplasia. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010:294.

12. Thway K, Fisher C. Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis in small intestine associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Ann Diagn Path. 2009;13:50-54.