Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 12

11 December 2019

CASE I: MSKCC/WMC/RU HB (JPC 4032968).

Signalment: Young adult, intact female Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus)

History: Both animals are from the same group of eight hamsters that were shipped together three weeks prior to being experimentally inoculated with Leishmania donovani. All animals were administered intraperitoneal preparations of Leishmania derived from tissue homogenates of previously infected hamsters. Shortly after treatment, seven of the eight animals became acutely lethargic and dehydrated with perineal staining. Multiple animals were found dead and the remainder with euthanized as clinical signs progressed.

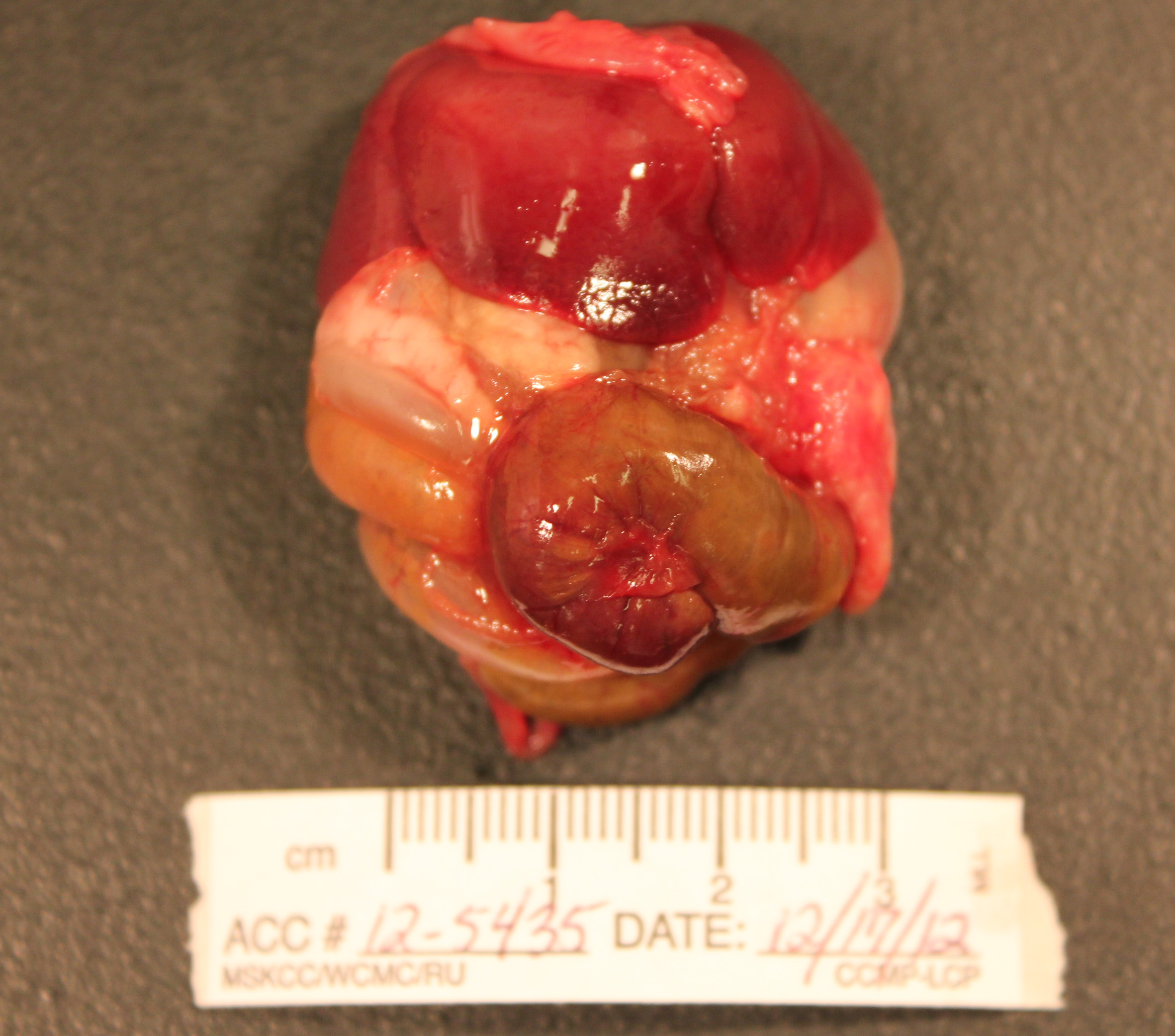

Gross Pathology: The abdomen is moderately distended and there is mild perineal fecal staining.

Approximately 1-2ml of slightly turbid, serosanguinous fluid is present within the abdominal cavity. The mesentery is markedly thickened and diffusely white. Intestinal loops are firmly adhered to one another by mesenteric adipose tissue which envelopes the spleen and uterus, and is adhered to the visceral surface of the liver. Mesenteric lymph nodes are enlarged and poorly demarcated, blending into the surrounding mesentery. The cecum is moderately distended by feed material and the distal colon is empty.

The liver is enlarged (10.6% of bodyweight) with rounded margins, and is diffusely pale tan and friable with an enhanced reticular pattern. The kidneys are mildly enlarged, pale tan and swollen. The pancreas and peripancreatic adipose tissue are mottled tan to red and firm.

In the right cranial lobe of the lung, there was a firm, poorly demarcated structure palpable in the parenchyma. On the serosal surface of the left middle lobe, there were multiple plaque-like, sharply circumscribed, brown depositions of material observed (histologically identified as multifocal calcifications of pulmonary basal membranes with reactive histiocytic inflammation).

Laboratory results:

Cytology of the abdominal fluid revealed moderate numbers of small to medium sized lymphocytes, fewer large round cells, and small numbers of mesothelial cells and macrophages. Impression smears of the liver were highly cellular and composed predominantly of large round cells, approximately 10-20um in diameter, with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, large round nucleus, finely clumped chromatin, multiple nucleoli, and a small amount of basophilic cytoplasm.

Microscopic Description:

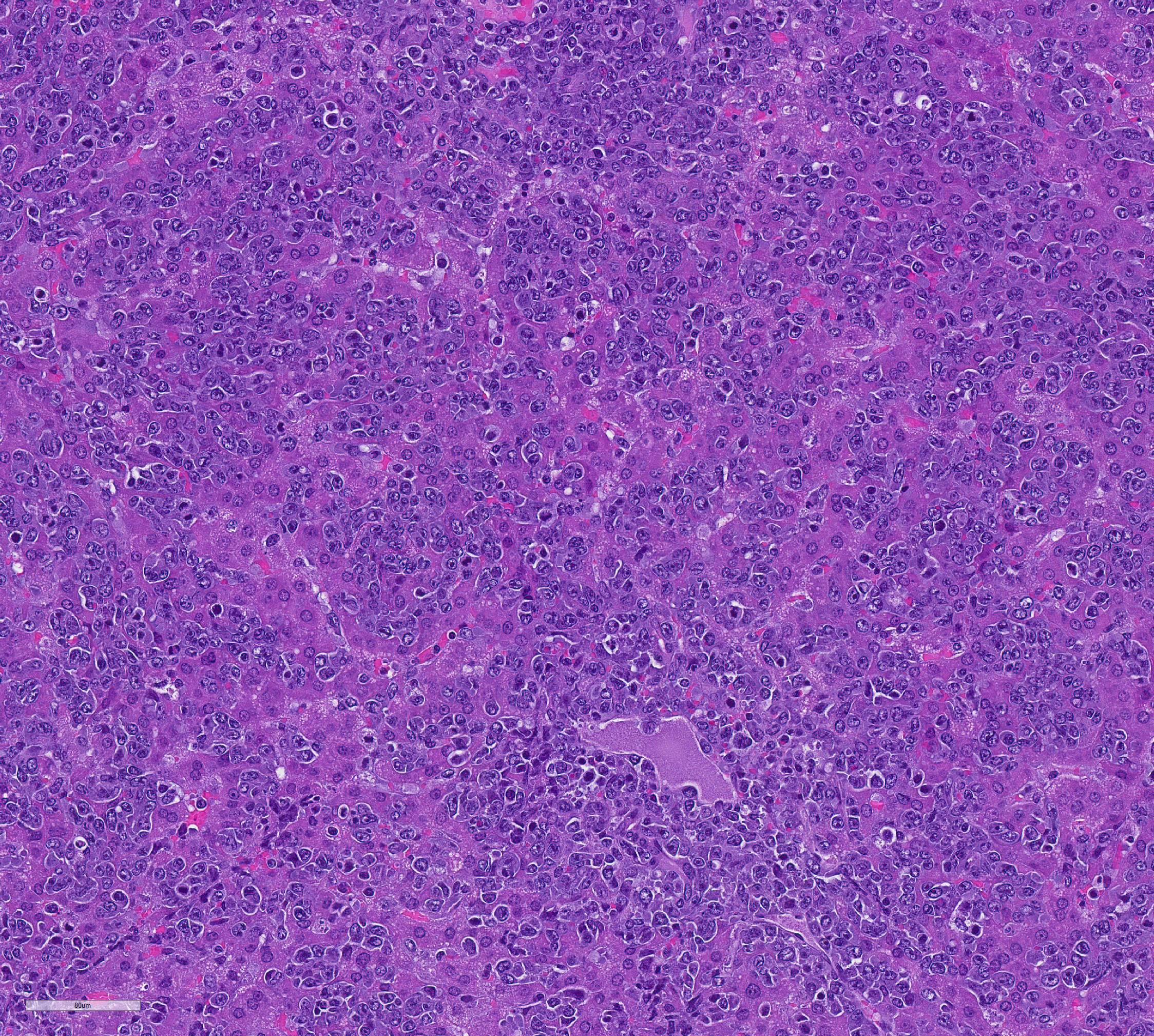

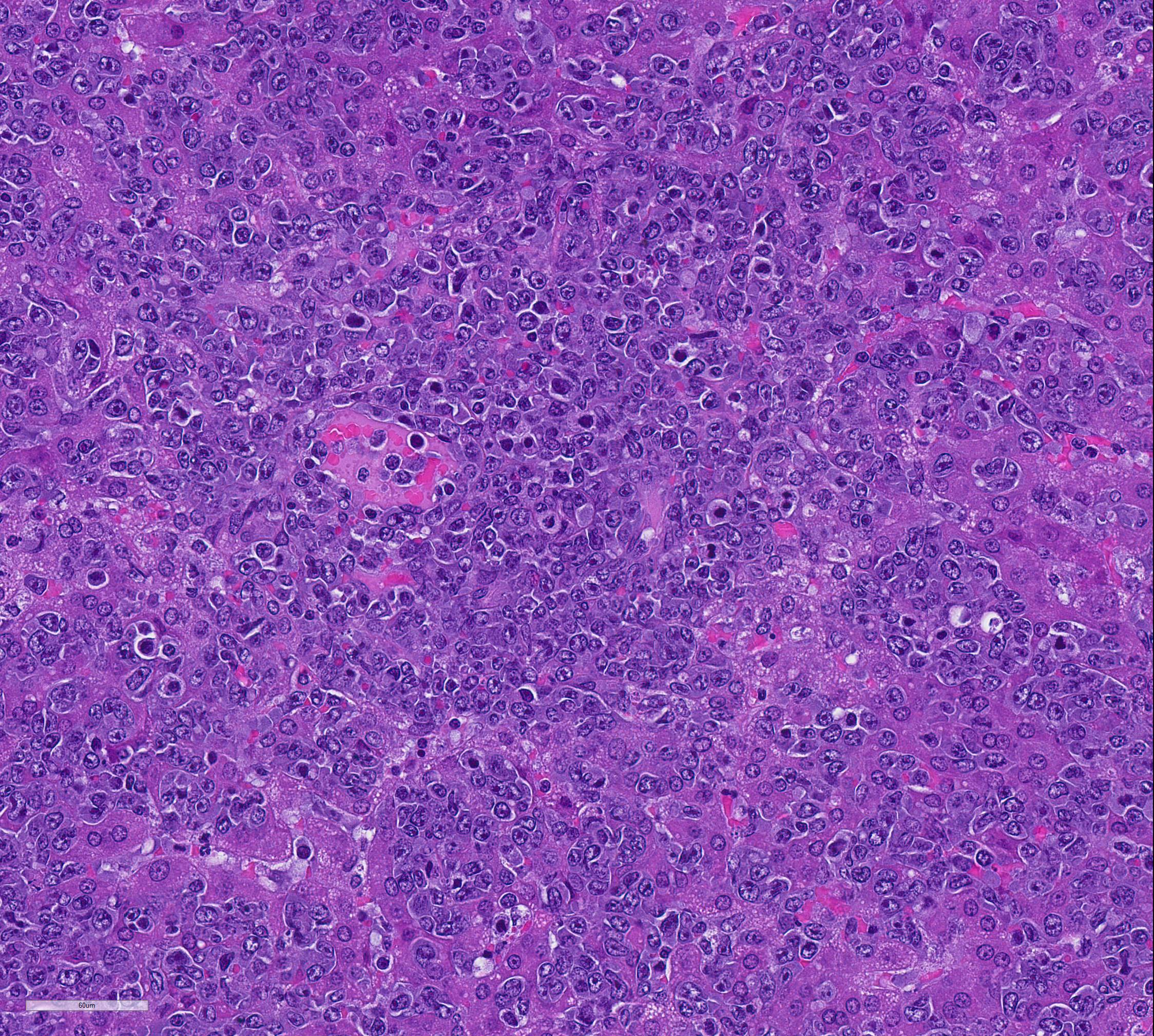

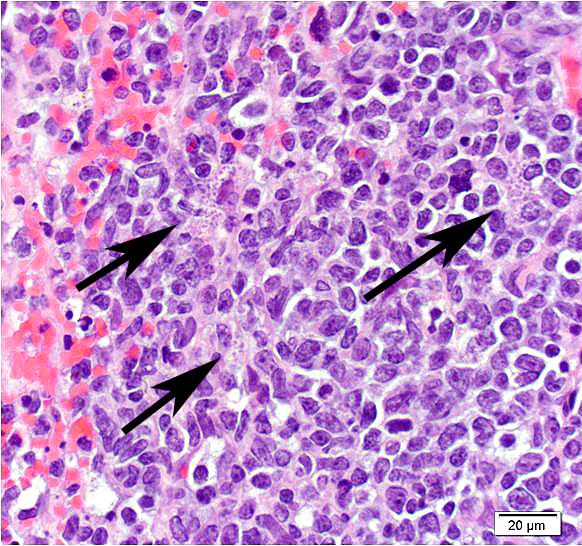

Mesentery including mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen and pancreas (variably includes small intestine): A poorly demarcated neoplastic infiltrate dissects throughout the mesentery which is extensively adhered to the splenic capsule, pancreas, mesenteric lymph nodes and intestinal serosa. Neoplastic round cells are arranged into densely cellular, unencapsulated sheets that variably efface the splenic and lymph node parenchyma and extensively disrupt the small intestinal muscularis and mucosa. Neoplastic cells have indistinct margins, a moderate amount of amphophilic cytoplasm and 10-15um diameter, round nuclei with coarsely stippled chromatin and variably conspicuous nucleoli. Frequent cells are necrotic and tingible body macrophages are scattered throughout the infiltrate. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are moderate and up to 7 mitotic figures are present per high power field (x400). Large areas of acute coagulative necrosis are scattered throughout mesenteric lymph nodes, variably accompanied by aggregates of fragmented mineral material (dystrophic mineralization). Scattered macrophages in remnant subcapsular sinuses and at the margins of necrotic foci contain dozens of oval-shaped, 2-3um diameter, intracytoplasmic protozoa with a 1-2um, basophilic nucleus and a variably distinct, perpendicular kinetoplast (Leishmania amastigotes).

Liver: An intense neoplastic infiltrate diffusely percolates throughout hepatic sinusoids, disrupting hepatic cords, obscuring portal tracts and lining the tunica intima of frequent central veins. Frequent hepatocytes are dissociated with hypereosinophilic cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclei (necrosis).

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Mesentery including mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, pancreas and small intestine: Lymphoma

Mesenteric lymph nodes: Severe, acute, multifocal to coalescing, necrotizing splenitis with intrahistiocytic protozoa, etiology consistent with Leishmania sp.

Contributor Comment All eight hamsters received intraperitoneal preparations of Leishmania donovani derived from tissue homogenates of previously infected animals. Within three weeks, all animals became acutely lethargic and dehydrated or died acutely. Gross and histologic findings were similar in all animals, which were characterized by intense mesenteric infiltrates of neoplastic round cells. The histologic appearance of neoplastic cells is most consistent with lymphoma. Consistent with the experimental history, scattered macrophages located at the margins of necrotic foci within the mesenteric lymph nodes contained cytoplasmic amastigotes. All animals were inoculated with L. donovani as part of a study investigating host immunoregulation of visceral leishmaniasis.

Protozoa of the family Trypanosomatidae, genus Leishmania cause a spectrum of disease in people ranging from subclinical infection to severe, disseminated cutaneous, mucocutaneous and visceral disease. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is the most severe form of disease and may be fatal. Leishmania donovani is the predominant cause of VL in East Africa and India, whereas L. infantum and L. chagasi predominate in the Mediterranean and Latin America, respectively.1 The domestic dog is an important reservoir host for the latter two species. Humans are the only known reservoir of L. donovani.

Leishmania sp. proliferate in the midgut of phlebotomine sandflies where the flagellated leptomonad form appears as a leaf-shaped promastigote.5 Upon transmission to mammalian hosts, the organism assumes the aflagellated, obligate intracellular leishmanial form, or amastigote, which proliferates within macrophages and dendritic cells of susceptible hosts. These are approximately 2um diameter with a basophilic nucleus and perpendicularly oriented kinetoplast.

Host susceptibility to clinical disease relates to the Leishmania species involved and individual host factors such as immunocompetence. In susceptible hosts, VL may cause persistent fever, leukopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia and hepatosplenomegaly. Chronic immune-complex deposition may result in glomerulonephritis in people. Clinical and pathologic findings are similar in dogs, consisting predominantly of hepatic granulomas, splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy.5

The Syrian hamster is a widely used experimental model of VL, developing clinical signs and lesions that recapitulate human and canine disease including splenic lymphoid depletion, hepatic granulomas and amyloid deposition within the spleen and liver.1 Glomerulonephritis and inflammatory myopathies have also been reported. Despite developing clinical disease and lesions that closely approximate human VL, a lack of reagents and a poor immune response to infection are limiting factors in the Syrian hamster model, particularly for evaluation of vaccination strategies. Murine models have also been utilized to identify genes that play an important role in the pathogenesis of VL. In some mouse strains (eg. CBA) genetic resistance is conferred by the gene Slc11a1, which encodes a phagosomal membrane protein that limits intracellular Leishmania multiplication by Fe2+ deprivation.1 Susceptible mouse strains (eg. BALB/c, C57BL/6) with impaired Slc11a1 expression are susceptible to Leishmania; however, even susceptible mice typically overcome visceral infection.

Given the severity of the neoplastic infiltrate in all animals, the cause of death in these animals was determined to be lymphoma, rather than visceral leishmaniasis. Outbreaks of transmissible lymphoma due to hamster polyomavirus (HaPV) infection have been reported in hamster colonies causing lymphoma epizootics that affect up to 80% of young, naïve animals.2 HaPV was initially described in association with epitheliomas in older hamsters.3 Tumors arise from the epithelium of the hair follicle forming keratin-filled, cystic masses. Large numbers of virus particles are detectable in keratinizing cells of epitheliomas. This contrasts with HaPV-associated lymphomas, which do not contain infectious virus, although thousands of copies of extrachromosomal viral DNA are present within neoplastic cells. Ha-PV associated lymphoma typically arises in the mesentery with infiltration of the liver, kidney, thymus, and other viscera. Tumors are usually lymphoid, although erythroblastic, myeloid and reticulosarcomatous forms may occur3. In enzootically infected, older hamsters the virus persists subclinically in the kidneys with intermittent shedding in urine.

In this case HaPV infection was suspected based on the clinical presentation but could not be confirmed by PCR (IDEXX RADIL). Lymphoma is rare in young hamsters and the rapid neoplastic progression in this group is highly suggestive of epizootic HaPV.2 Ultrastructural imaging was not pursued as virus particles are not typically present in neoplastic lymphocytes.

It is unclear whether affected animals developed lymphoma prior to arrival at our facility or whether intraperitoneal Leishmania inoculation was the source of the tumor. It is possible that the tissue homogenate from which the inoculum was derived was infected with HaPV. It is also possible although somewhat less likely, that the donor animal had spontaneous lymphoma that was then transmitted to subsequent animals in the tissue homogenate. Transmissible tumors in the dog (canine transmissible venereal tumor) and Tasmanian devil (devil facial tumor disease) are associated with downregulation of tumor cell MHC expression, allowing successful allograft and proliferation in the absence of a host immune response.4

Contributing Institution:

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

1275 York Ave

New York, New York, 10065

http://www.mskcc.org/research/comparative-medicine-pathology

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Liver, spleen, omentum, intestine, pancreas:

Lymphoma.

2. Liver, spleen, omentum, pancreas, intestine, macrophages: Intracytoplasmic

amastigotes, rare.

JPC Comment: The contributor has provided an excellent review of leishmaniasis as well as the use of the Syrian hamster as the animal model for its visceral form. Leishmania has appeared multiple times in the Wednesday Slide Conference in the dog (WSC 2015-2016, Conf 17, Case 3, WSC 2013-2014 Conf 3, Case 3, WSC 2009-2010, Conf 13, Case 4, @WC 2007-2008, Conference 5, case 2). It has appeared twice in the hamster (WSC 1998-1999, Conf 10, Case 2 and WSC 1971-1972, Conference 22, case 2). The reader is directed to the comments on these cases for additional information.

The history of

leishmaniasis is an ancient one, with identification of Paleoleishmania in

fossilized form within the proboscis and gut of 100-million-year-old fly

preserved in amber. Written records of cutaneous leishmaniasis begin in

Assyrian tables describing "oriental sore", and Leishmania DNA has been

recovered from Egyptian and Peruvian mummies. Evidence for immunization against

Leishmania dates back to ancient Arabia, whose physicians vaccinated children

with exudate from the sores of active lesions or exposed them to sandflies to prevent

the occurrence of disfiguring facial scars. Numerous reports in more modern

times of "Allepo", "Jericho" and "Baghdad boil" are present in Middle Eastern

literature, and numerous reports from explorers of the New World, including

Francisco Pisarro described a similar scarring condition. Visceral leishmaniasis,

or kala-azar, was first described by military surgeon Willian Twining in 1827

in India. Scottish pathologist William Boog Leishman was the first to observe

and describe the amastigotes of Leishmania in autopsy of soldiers in

India as well as infected rats. Weeks later, an Irish pathologist working at

Madras veterinary college identified similar structures in Indian subjects with

splenomegaly and recurring fever. In 1903, Dr. William Ross identified the

structures first described by Leishman and Donovan as a new species and not a

degenerate trypanosome or piroplasm (as was currently thought at the time) and

named the agent Leishmania donovani.

Currently, visceral leishmaniasis remains a significant problem in 14 high-risk

tropical countries, but numbers of cases, especially in India, appear to be on

the decline. International travel and international transport of blood

products (blood is not routinely checked for anti-leishmanial antibodies) has

resulted in cases of VL in non-endemic countries. Ongoing instability in the

Middle East and refugee crises also helps to import cutaneous forms of

leishmaniasis into areas where it formerly was at a very low level.

Unfortunately, in the submitted sections, the changes associated with visceral leishmaniasis are greatly overshadowed by the large cell lymphoma presumably resulting from activation of hamster polyomavirus. Few of the participants noticed the presence of amastigotes within macrophages, as amastigote-laden macrophages were often overshadowed by the profound neoplastic infiltrate and the scattered apoptotic cells contained within.

References:

1. Nieto A et al. Mechanisms of resistance and susceptibility to experimental visceral leishmaniosis: BALB/c mouse versus syrian hamster model. Vet Res. 2011;42(1):39

2. Percy DH and Barthold SW; Hamster. In: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, Eds. Percy DH and Barthold SW, 3rd ed. pp181-183. , Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, IA, 2007

3. Scherneck S, Ulrich R and Feunteun J. The hamster polyomavirus--a brief review of recent knowledge. Virus Genes. 2001;22(1):93-101

4. Siddle HV et al. Reversible epigenetic down-regulation of MHC molecules by devil facial tumour disease illustrates immune escape by a contagious cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(13):5103-8

5. Steverding D. The history of leishmaniasis. Parasit Vect 2017; (10):82-89.

6. Valli V; Hematopoietic System. In: Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, Ed. Maxie GM, 5th ed., pp.302-304, Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007