CASE 3: N542/18J (4137397-00)

Signalment:

5 month-old, entire male, Hungarian vizsla, dog (Canis lupus familiaris)

History:

The dog lived on a farm, had been vaccinated and treated for parasites, had no prior medical history, and had never travelled outside of Ireland. The dog was referred to the UCD veterinary hospital with a 4-day history of a progressively developing well-demarcated, ulcerative and exudative skin lesion on the dorsal aspect of the left metacarpal region. This had been associated with excessive licking, swelling of the left pad, and a mild weight-bearing lameness. Clinical signs of lethargy, anorexia, pyrexia (39.6ºC) and vomiting had followed the onset of the cutaneous lesions.

The dog was managed with intravenous fluid therapy (5 ml/kg/hour, anti-emetic (maropitant 1 mg/kg IV SID), and gastroprotectant (omeprazole 1 mg/kg IV BID) and broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy (amoxicillin-clavulanate).

On the day of admission, to obtain punch biopsies of the skin lesions, the dog was intravenously sedated with butorphanol 0.3 mg/kg and medetomidine 1 ug/kg. Five minutes later, a short (approximately 30 seconds) but violent episode of generalized tonic-clonic seizure activity associated with autonomic signs occurred. Intravenous diazepam was administered (0.5 mg/kg IV) and the dog was admitted to the intensive care unit to complete this procedure and to monitor the patient. Additional seizure activity, which responded to intravenous diazepam (0.5 mg/kg) followed by levetiracetam (20 mg/kg), was noted 12 hours later. On the third day of hospitalization, repeat hematology, biochemistry and urinalysis identified moderate thrombocytopenia and severe azotemia and hyperphosphatemia despite the concurrent administration of intravenous fluid therapy. Given the clinical signs and laboratory results (particularly the rapidly progressing azotemia), a tentative diagnosis of cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy (CRGV) was made. Despite the very guarded prognosis the option of intensifying the supportive and monitoring care was offered to the owner. This was declined and humane euthanasia was performed.

Gross Pathology:

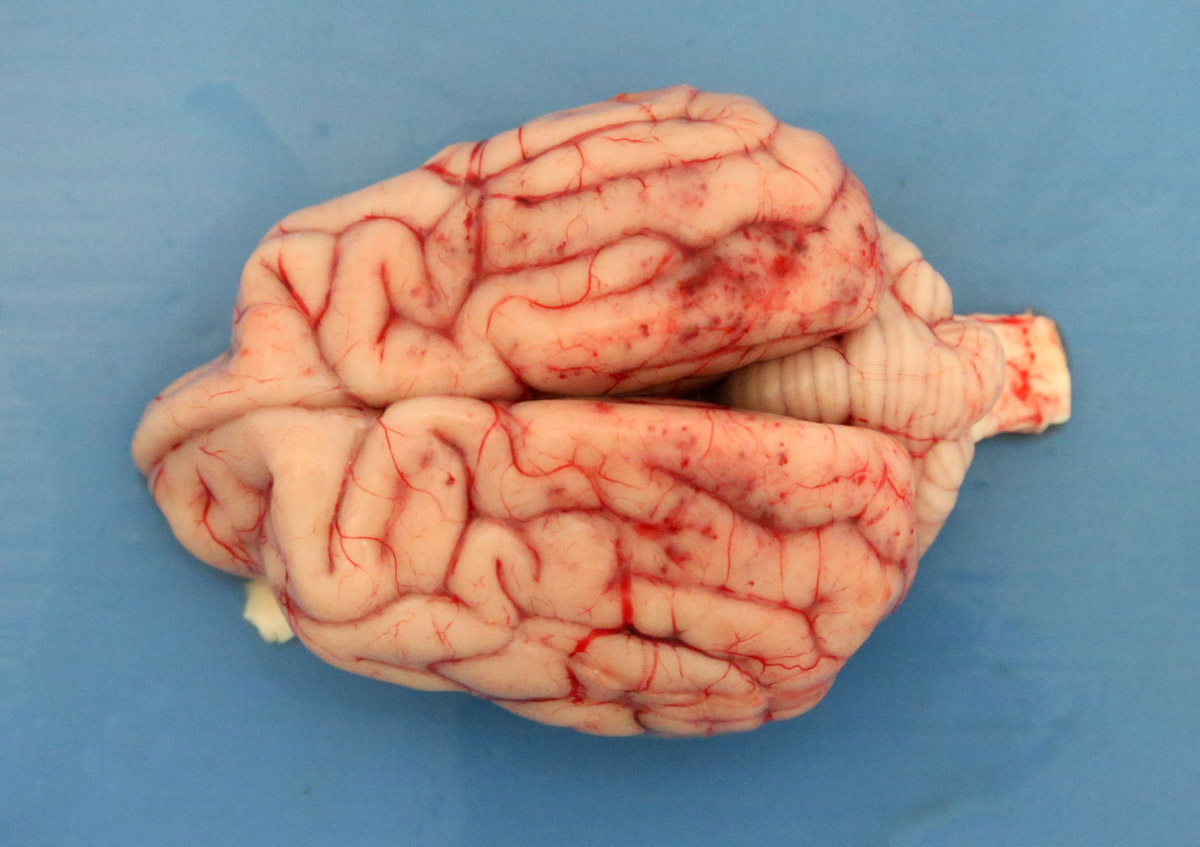

2-3 cm, ulcerating, encrusted, red-brown cutaneous lesion on dorsal aspect of right metacarpus extended into the subcutis. Pronounced petechiae and ecchymoses over serosal surfaces (particularly gastric, small and large intestinal serosae). The gastric and small and large intestinal walls were transmurally edematous. Two liters of pale-yellow tinged aqueous fluid was recovered from the peritoneal cavity. Pulmonary congestion/hemorrhage, especially dorsocaudally. Multifocal hemorrhagic infarcts (1-2 mm) scattered throughout cardiac ventricular myocardia. Petechiae over pancreas and bilaterally over renal cortices with cortices diffusely reddened and wet on sectioning. Petechiation within leptomeninges.

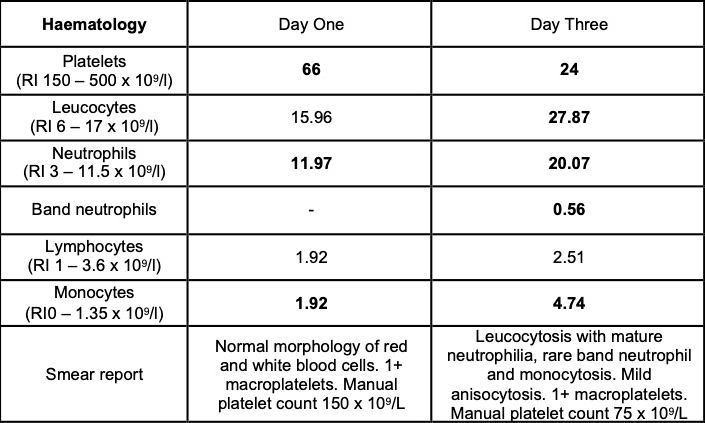

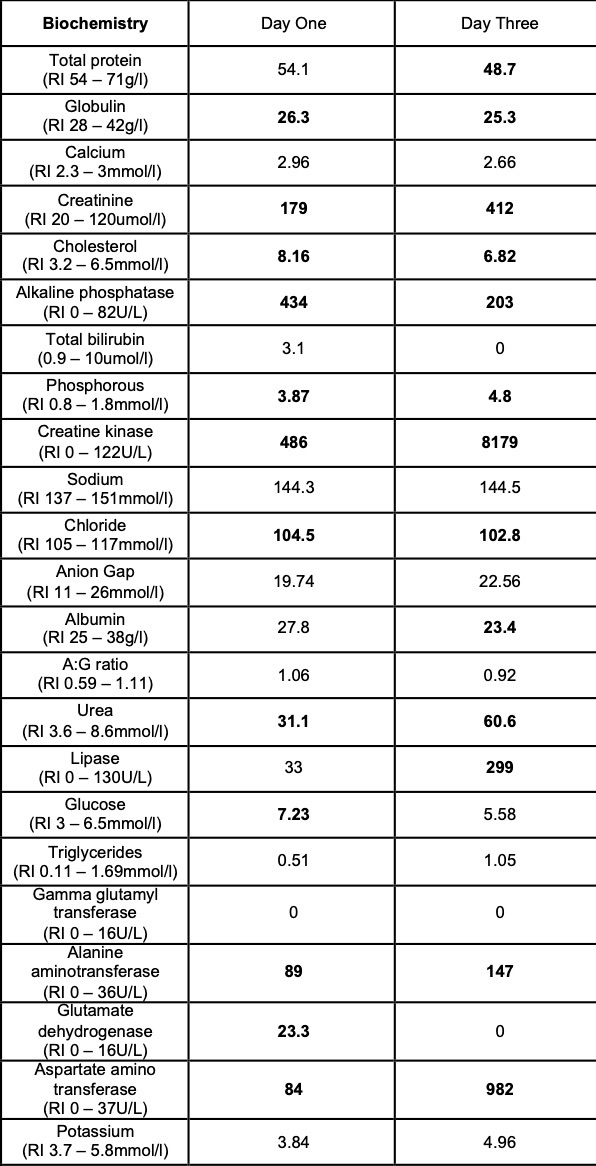

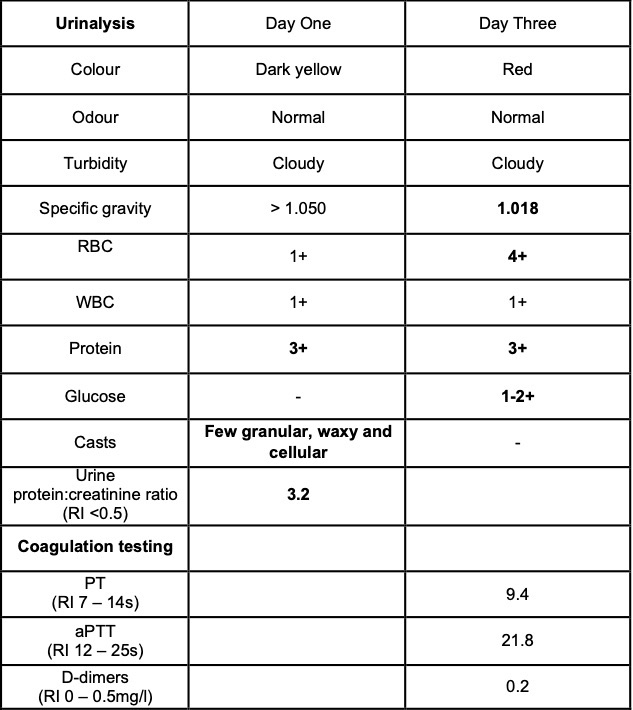

Laboratory results:

Selected laboratory results on days 1 and 3 of hospitalization (values outside normal ranges highlighted in bold). Key findings: thrombocytopenia, mild hypoalbuminemia and azotemia.

Microscopic description:

Diffusely, glomeruli exhibit extensive segmental to global intravascular coagulation, necrosis, and hemorrhage (thrombotic microangiopathy). Arterioles at the glomerular vascular pole also feature luminal thrombosis, along with transmural and circumferential eosinophilic hyalinized material and karyorrhectic debris (fibrinoid necrosis). Necrotic vessels are surrounded by aggregates of admixed intact and degenerate neutrophils that extend into the adjacent interstitium where there is accompanying marked hyperemia and hemorrhage. Larger caliber cortical arterioles also feature hyalinization of their walls with accompanying karyorrhectic debris. Multifocally, contiguous transverse cross-sections of cortical tubules exhibit epithelial nephrosis and luminal hyaline to more granular casts. Casts in medullary tubules also vary from hyalinized to palely eosinophilic and finely granular in appearance.

Martius scarlet blue staining of renal lesions confirms extensive glomerular intravascular thrombosis and fibrin within necrotic arteriolar walls.

Additional Findings

Skin lesions: extensive deep ulceration with dense fibrinocellular exudate (admixed intact and degenerate neutrophils and macrophages) extending into subjacent fibrovascular tissue, dermis and subcutis with widespread microthrombi.

Heart: multifocal acute severe myocardial necrosis with subtle dystrophic mineralization and mild to moderate associated leucocytic infiltrates.

Small intestine: transmural fibrinoid necrosis and microthrombosis with associated luminal inflammation and hemorrhage, mucosal necrosis/erosion, submucosal edema and smooth muscle necrosis/hemorrhage.

Brain: focally within cerebral grey matter and meninges the walls of small caliber arterioles feature transmural and circumferential eosinophilic hyalinized material and cell debris (fibrinoid necrosis). There is associated edema and mild inflammation in the surrounding parenchyma.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Kidney: glomerular fibrinoid degeneration and microthrombosis (thrombotic microangiopathy), acute, severe with attendant cortical tubular necrosis.

Contributor's comment:

The clinicopathological features of this case are consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy (CRGV), an idiopathic vascular disease which causes predominantly cutaneous and renal lesions in dogs. The condition was first described in breeding and racing greyhounds between the ages of 6 months and 6 years in 1988 associated with a specific racetrack in Alabama in the USA and hence given the pseudonym 'Alabama Rot'.1

Since 1988, CRGV has been diagnosed in other parts of North America, Germany and the United Kingdom and in breeds of dog other than greyhounds.1,3,7 Spaciotemporal 'clusters' of dogs with the condition were reported in the UK between 2012 and 2014.3,8,9 This is the first case to be reported on the island of Ireland.

The hallmark of CRGV is renal thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), a pathologic process that features endothelial damage, thrombosis and red cell shearing.1,3,6 Thrombosis is also described in dermal, gastric, enteric and colonic arterioles.1,2,3 TMA particularly targets glomerular capillaries resulting in acute renal glomerular necrosis. Cutaneous lesions feature epidermal necrosis, subcutaneous hemorrhage, fibrinoid necrosis of small arterioles, mixed inflammatory infiltrate and thrombosis.1,3,6 The current case developed seizure episodes shortly after admission to the UCD veterinary hospital. Such neurological deficits have been described in previously where histopathology found multifocal neuronal necrosis, hemorrhage and edema.7 Similarly, in the current case, thrombosis with associated necrosis, hemorrhage and inflammation was observed in cerebral grey matter. Ultimately TMA results in consumptive thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia and multiorgan failure.3,6

Ultrastructural examination suggests glomerular endothelial damage is a central early event in the pathogenesis of CRGV.2,3 Changes described include: endothelial swelling, detachment, and necrosis; membranous whorl formation; and platelet adhesion and aggregation. This is followed by narrowing of capillary lumens and thickening of capillary walls by the subendothelial accumulation of flocculent, amorphous, variable electron-dense material, along with erythrocytes, cellular processes, and fibrin. Aetiologic agents or electron-dense deposits typical of immune complexes have not been observed.

TMA may be associated with underlying conditions, such as malignant neoplasms, administration of certain chemotherapies and other drugs, transplantation, and sepsis.6 While the ingestion of bacterial-associated shiga toxin and other factors are suggested etiologies of CRGV, studies have failed to consistently incriminate shiga toxin or indeed particular bacteria or viruses.1,3 Similar to the situation pertaining at the race-track in Alabama in the 1980s, spatiotemporal clustering of CRGV has occurred in the UK: in the New Forest region between February and March 2013 and between April 2015 - 2017 and in Manchester between February and April 2014.8,9 Although this 'clustering' may have been a consequence of heightened awareness of the condition in these areas at these times, there remains the possibility of common aetiological factors linked to the local environment or to seasonality: cases were generally associated with woodlands, increasing mean maximum temperatures in winter, spring and autumn, increasing mean rainfall in winter and spring and decreasing cattle and sheep density.8,9 Two UK Kennel Club breed groups ? 'hounds' (odds ratio [OR] 10.68) and 'gun dogs' (OR 9.69) - had the highest risk of a diagnosis of CRGV compared with terriers, while CRGV was not diagnosed in toy breeds.8 Interestingly, this UK study found that Hungarian vizslas, the breed of dog involved in this case, were one of the breeds that had an increased odds of developing CRGV when compared with crossbreds.

Clinical pathology findings include azotemia, hypoalbuminemia, hyperbilirubinemia, increased alanine transaminase and creatine kinase activities, non-regenerative anemia, thrombocytopenia, presence of schistocytes, burr cells and acanthocytes on blood smears, isosthenuria, hemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria, proteinuria, glucosuria and presence of casts in the urine sediment.1,3,7 The prognosis is considered guarded for dogs that develop azotemia, and particularly oligoanuric acute kidney injury, as a result of CRVG, although intensive medical intervention has been successful in some cases. 1,3

Contributing Institution:

Room 012, Veterinary Sciences Centre, School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

http://www.ucd.ie/vetmed/

JPC diagnosis:

Kidney: Vasculitis, necrotizing, glomerular and arteriolar, diffuse, severe, with thrombosis, extensive tubular necrosis, and proteinosis.

JPC comment:

The contributor provides a concise summary of this case and expands on the background of three cases in Ireland. Of the described cases, two were vizsla dogs, a breed previously reported to experience CRGV at higher rates. Unfortunately, a common etiology was not identified, though the cases occurred in similar environments (woodland), and two cases were geographically similar (within 7 miles, 4 years apart).5

Cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy (CRGV) falls under the umbrella of thrombotic microangiopathies (TMA), as stated by the contributor. The other reported TMA in animals is hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), reported in dogs, cats, rabbits, calves, and horses. Currently, there appear to be a variety of possible initiators of endothelial damage, which start the events leading to microthrombi in small vessels. Some possible causes identified in human TMAs include an ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13) deficiency, complement dysregulation, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), systemic lupus erythematosus, certain drugs, infectious causes, and others. Given the epidemiology of this disease, which indicates a seasonality, and the fact that it primarily affects dogs with an active outdoor lifestyle in woodland areas, there may be a smaller list of causes for veterinary species. The list of infection associated causes of TMAs in humans include Shiga-toxin, Campylobacter jejuni, Streptococcus pneumonia, HIV, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, parvovirus, BK virus (polyomavirus), and influenza. The possibility that there is an infectious agent or toxic cause influenced by the season and environment cannot yet be discounted.4

References:

- Carpenter JL, Andelman NC, Moore FM, King Jr NW: Idiopathic cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy of greyhounds. Vet Pathol 25(6):401-407, 1988

- Hertzke DM, Cowan LA, Schoning P, Fenwick BW: Glomerular ultrastructural lesions of idiopathic cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy of greyhounds. Vet Pathol 32(5):451-459, 1995

- Holm LP, Hawkins I, Robin C, et al: Cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy as a cause of acute kidney injury in dogs. Vet Rec 176(15):384, 2015

- Holm LP, Stevens KB, Walker DJ. Pathology and epidemiology of cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy in dogs. J Comp Path. 2020;176:156-161.

- Hope A, Martinez C, Cassidy JP, Gallagher B, Mooney CT. Canine cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy in the Republic of Ireland: a description of three cases. Irish Veterinary Journal. 2019;72:13.

- Jepson RE, Cardwell JM, Cortellini S, Holm L, Stevens K, Walker D: Cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy, what do we know so far? Vet Clin Small Anim 49:745?762, 2019.

- Skulberg R, Cortellini S, Chan DL, Stanzani G, Jepson RE: Description of the use of plasma exchange in dogs with cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy. Front Vet Sci 5:161, 2018

- Stevens KB, O'Neill D, Jepson R, Holm LP, Walker DJ, Cardwell JM. Signalment risk factors for cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy (Alabama rot) in dogs in the UK. Vet Rec 183(14):448-454, 2018

- Stevens KB, Jepson R, Holm LP, Walker DJ, Cardwell JM. Spatiotemporal patterns and agroecological risk factors for cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy (Alabama rot) in dogs in the UK. Vet Rec 183(16):502-512, 2018.