Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 10

20 November 2019

Dr. Elise Ladouceur

Chief, Extramural Projects

Veterinary Pathology Services

Joint Pathology Center

CASE III: 19H4111

(JPC 4136173).

Signalment: Juvenile (approximately 2 months), unknown sex, bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps)

History: A recently-adopted juvenile bearded dragon presented for 2-3 day history of lethargy and neurologic abnormalities (star-gazing behavior, intermittent head-tilt, inability to ambulate). Coelomic distention and a significant amount of intestinal contents were observed upon trans-illumination. Severe lethargy and depression persisted following administration of antibiotics, therefore euthanasia and post-mortem examination was elected.

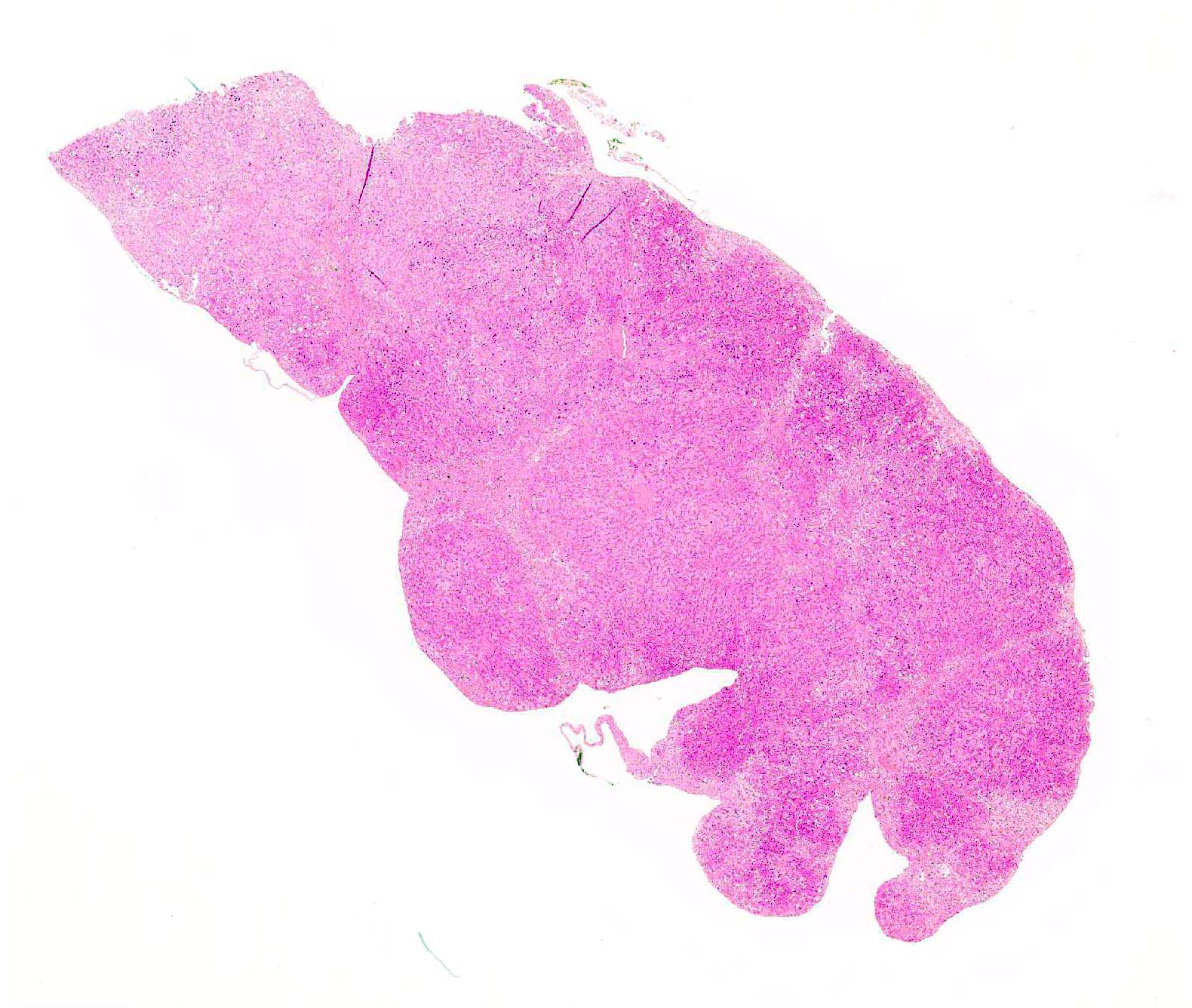

Gross Pathology: The body was considered to be thin and exhibited mild autolysis. The liver was markedly enlarged, diffusely pale yellow to tan, and nodular.

Laboratory results:

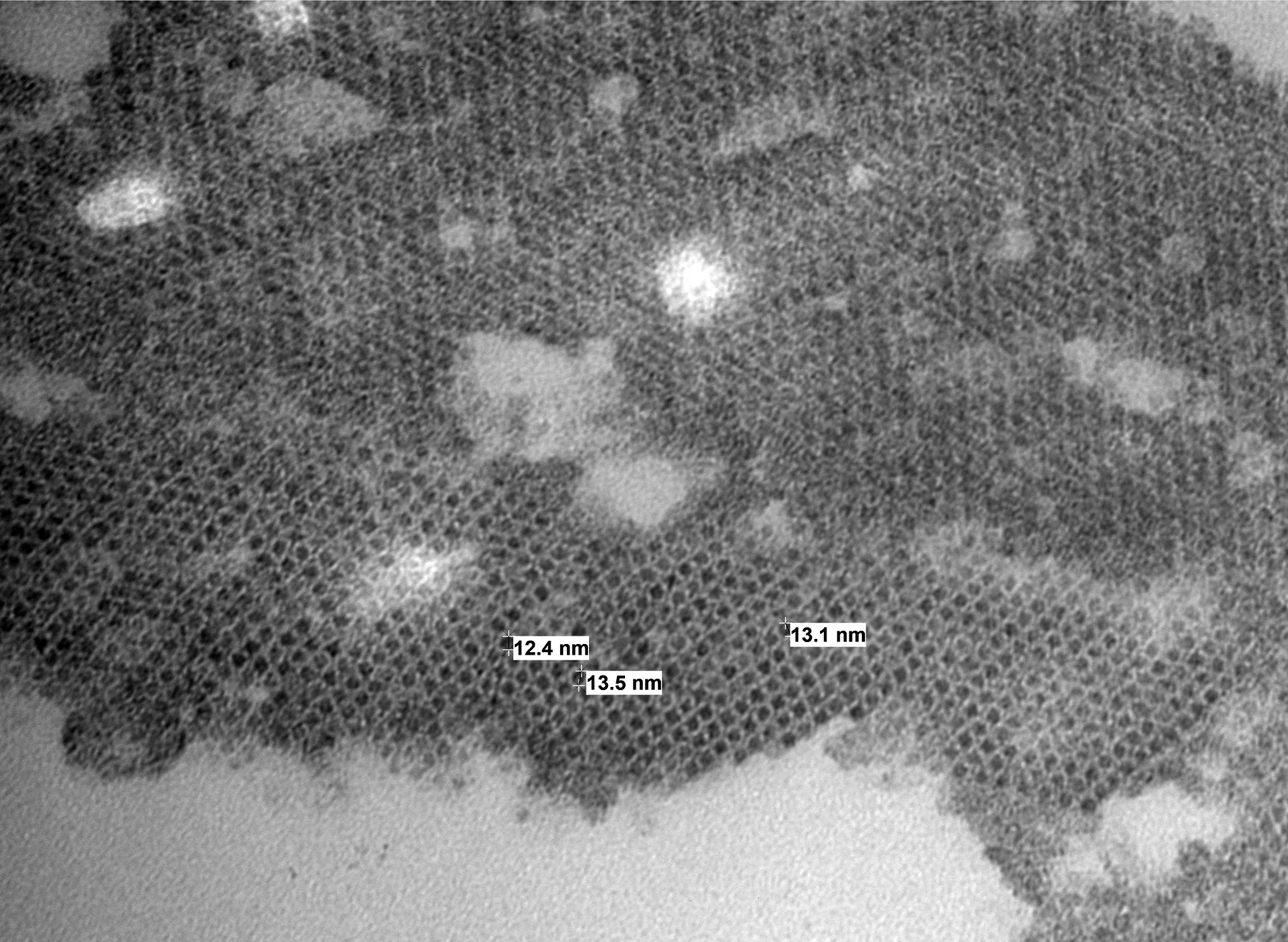

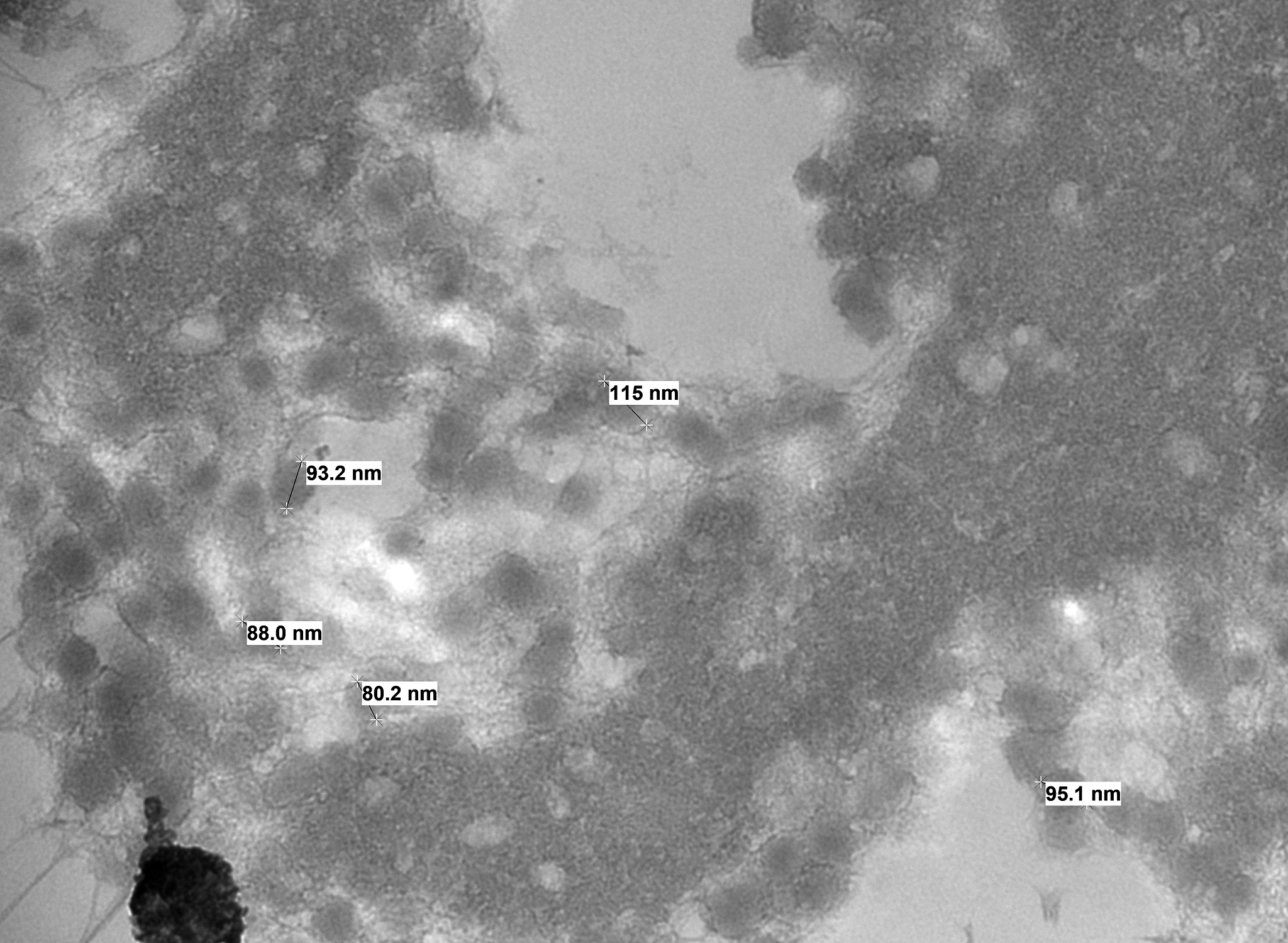

Electron microscopy results revealed intranuclear icosahedral virions consistent with adenovirus, and smaller icosahedral virions suspected to be dependovirus. Whole-genome sequencing confirmed bearded dragon adenovirus in liver samples.

Microscopic Description:

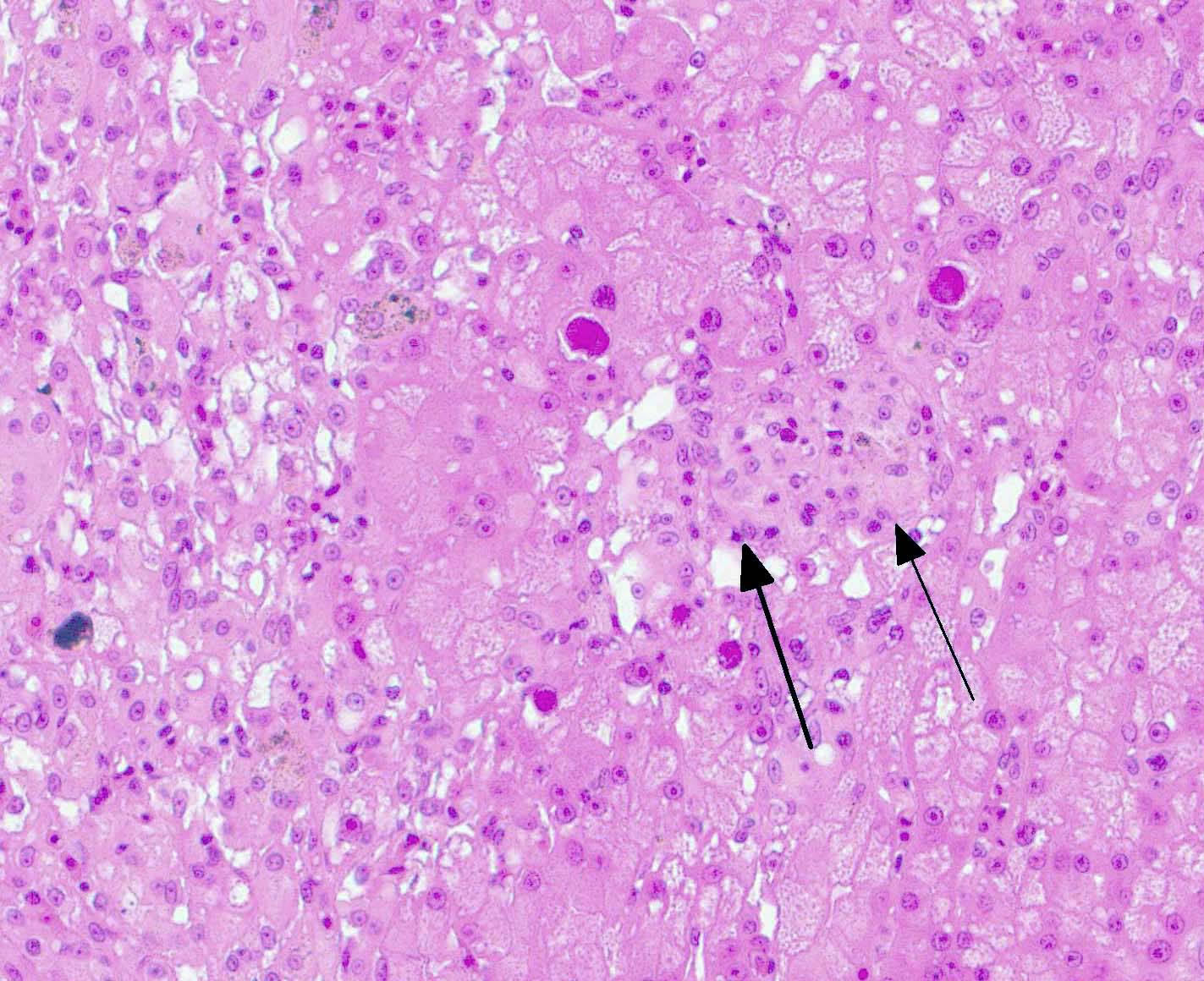

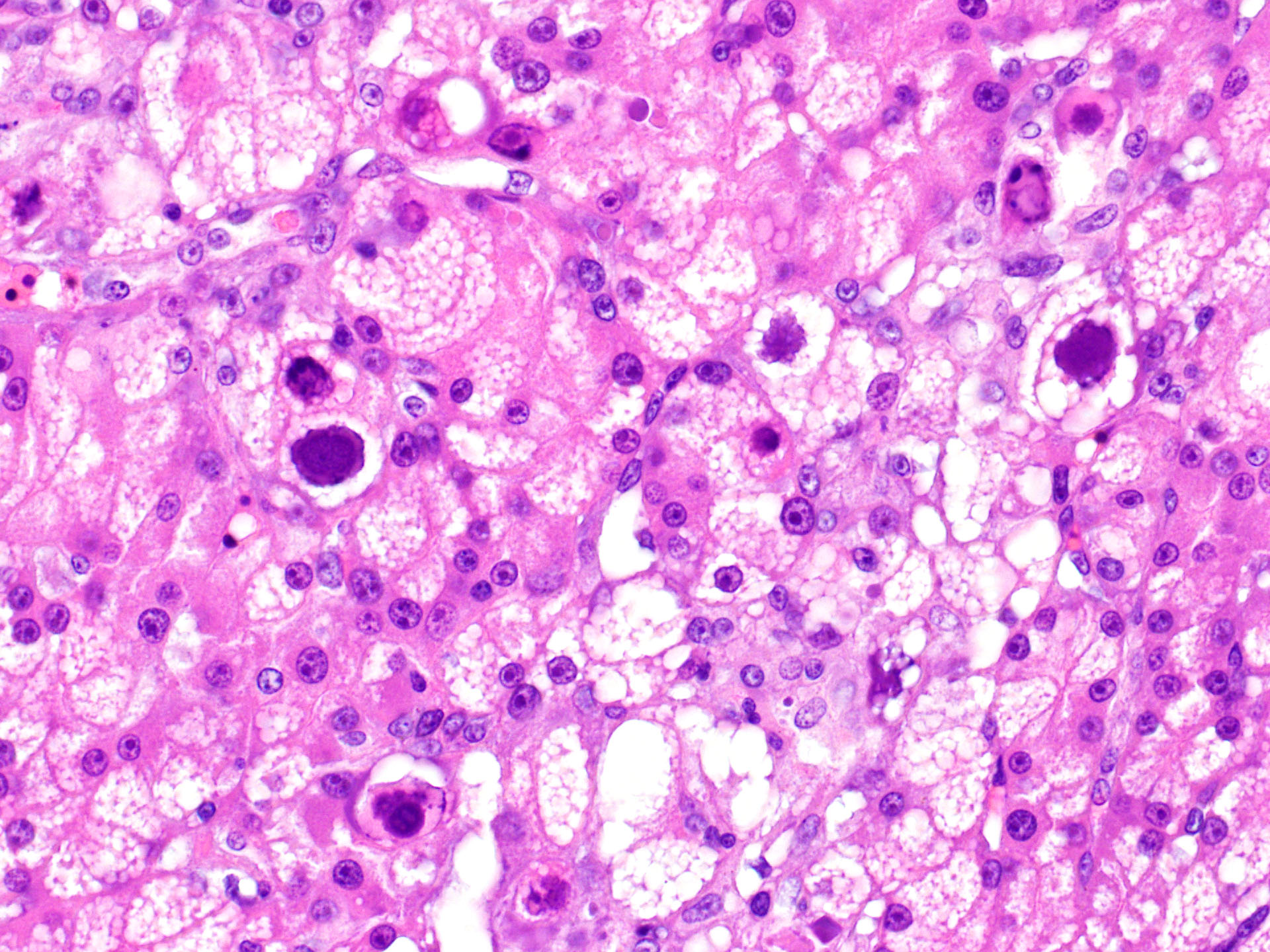

Liver: There is hepatocellular disintegration and loss with mild fibrosis and few discernable portal tracts. Diffusely hepatocytes display varying degrees of cytoplasmic microvesicular lipid type vacuolar change. Occasionally, individual or groups of hepatocytes are hypereosinophilic with pyknotic nuclei. In some areas, hepatic bile ducts are proliferative. Frequently, the hepatocyte nuclei are markedly enlarged (karyomegaly) with deeply basophilic round to irregularly-shaped intranuclear inclusions that occasionally displace the chromatin to the periphery. There are multifocal areas of hemorrhage and infiltrates of inflammatory cells consisting of heterophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages.

Other findings: (Not included in slide submission)

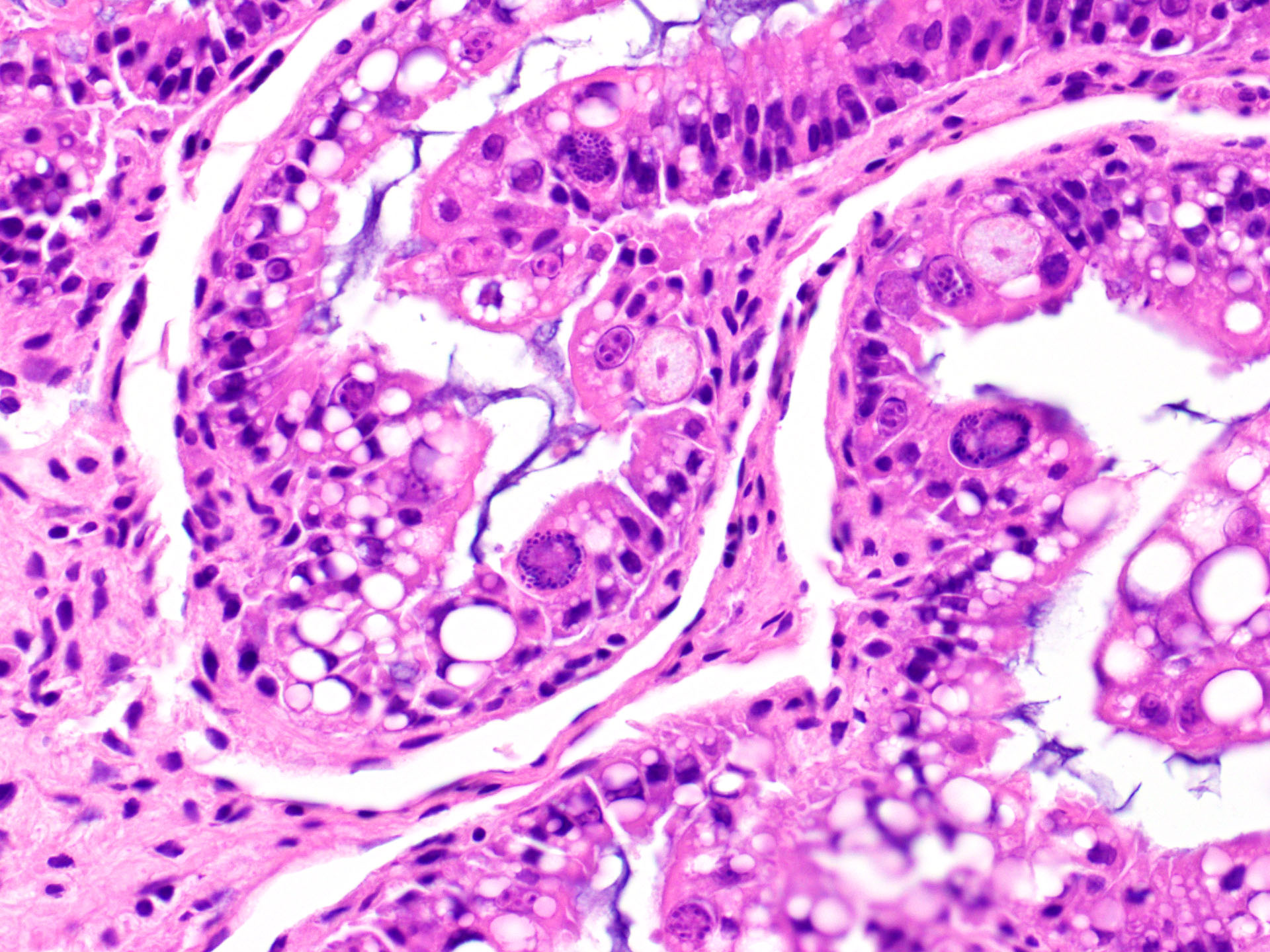

Intestine: There are moderate numbers of apicomplexan organisms in various stages of development within the intestinal mucosa. Mucosal enterocytes show intraepithelial microgametes and macrogametes. Some enterocytes appear degenerate and vacuolated with karyomegalic intranuclear basophilic inclusions. The lamina propria is infiltrated by a small number of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and heterophils.

Lungs: Occasional, pneumocytes have karyomegalic nuclei with intranuclear, basophilic viral inclusions.

Pancreas: Pancreatic acinar cells occasionally have karyomegalic nuclei with intranuclear, basophilic viral inclusions.

Kidney: Renal tubular epithelium occasionally have karyomegalic nuclei with intranuclear, basophilic viral inclusions.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, lymphocytic, random, multifocal with biliary hyperplasia, hepatocellular fatty degeneration, karyomegaly and basophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies, (consistent with adenovirus)

Intestine: Enteritis, lymphoplasmacytic, multifocal, moderate, with intraepithelial apicomplexans (coccidiosis) and intranuclear, basophilic inclusion bodies (consistent with adenovirus)

Contributor Comment: Adenoviruses are non-enveloped, linear, dsDNA viruses with an icosahedral nucleocapsid ranging in size from 80-110 nm. Agamid adenovirus-1 belongs to the Atadenovirus genera, one of five accepted Adenoviridae genera. It is the most widespread of atadenoviruses and has been described in other reptiles such as chelonians, snakes, crocodiles, and chameleons.7,9 Genomic sequencing techniques have facilitated the characterization of numerous other squamate viruses within this genera, including chameleonid adenovirus 1 in chameleons, eublepharid adenovirus 1 in leopard geckos and fat-tailed geckos, helodermatid adenovirus 1 in Gila monsters and Bearded lizards, scincid adenovirus 1 in blue-tongued skinks, and snake adenovirus 1 and 2 in various snake species.14

Agamid adenovirus-1 is a common infection of bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps), as well as other squamates. Clinical signs vary from asymptomatic or mild ill-thrift (e.g., weight loss, lethargy), to severe enterohepatic (e.g., diarrhea, weakness, anorexia) and neurological signs (e.g., head tilt, circling, opisthotonus) as well as death.1-3,7-11 Disease is thought to manifest from stress-associated viremia, afflicting juveniles more so than adults. Agamid adenovirus-1 is most prevalent among captive breeding colonies though has been isolated from free-range bearded dragons, which are native to Australia.3,6,9

Disease caused by adenoviruses in various species is typically enterohepatic or respiratory in nature.7,9 There are, however, exceptions to this generalization (see Table 1). Many species do not show outward clinical signs of adenovirus except in the presence of immunosuppression or another primary infection. Numerous cases of agamid adenovirus-1 are reported with concurrent coccidiosis (Isospora or Eimeria spp.) which also tend to be incidental, except in severe infestations or otherwise compromised bearded dragons.5,8,11 Other reported comorbidities include Cryptosporidium spp., fungal infections, and other viruses (e.g., dependovirus).7,12 Transmission is primarily fecal-oral, therefore, prevention is aimed at maintaining a hygienic environment and quarantining new colony additions.9,11

Antemortem diagnosis of agamid adenovirus-1 can be made via PCR on choanal-cloacal swabs at select diagnostic laboratories, which is preferred to serology due to lower sensitivity.3,4,6 Postmortem diagnosis is based on presumptive karyomegalic, basophilic, intranuclear adenoviral inclusions and necrosis, particularly within the liver. Viral inclusions may be visualized within hepatocytes, enterocytes, esophageal epithelium, myocardium, endocardium, lung, renal tubular epithelium, brain glial and epithelial cells, and/or within the pancreas.3,7,11 Other molecular techniques such as electron microscopy, in situ hybridization, and next gen sequencing are useful in obtaining a definitive diagnosis or further characterizing adenoviruses.1,3,4,8,14 Despite this virus being typically host-specific, phylogenetic evidence supports some cross-over and viral adaptation through co-evolution in novel host species.1,2,14

|

Genus |

Virus(es) |

Reported Disease/Syndrome |

|

Atadenovirus |

Agamid adenovirus 1 Duck adenovirus 1 Cervine adenovirus 1 Caprine adenovirus 1 Ovine adenovirus 7 |

Hepatitis, enteritis, encephalitis Egg drop syndrome Vasculitis, hemorrhagic disease, pulmonary edema None to mild respiratory disease None to mild respiratory disease |

|

Aviadenovirus |

Fowl adenovirus 2, 8, 11 Fowl adenovirus 4 Fowl adenovirus 1 Avian adenovirus 1 Turkey adenovirus 1 & 2 Duck adenovirus 2 |

Inclusion body hepatitis Hepatitis-hydropericardium syndrome virus Gizzard erosion Quail bronchitis virus Decreased egg production Hepatitis (rarely) |

|

Ichtadenovirus |

Sturgeon ichtadenovirus A

|

|

|

Mastadenovirus |

Canine adenovirus 1 Canine adenovirus 2 Bovine adenovirus Equine adenovirus 1 & 2 Porcine adenoviruses 1-5 Guinea pig Rabbit adenovirus 1 Goat adenovirus 2 Ovine adenovirus 1-5 Caprine adenovirus |

Infectious canine hepatitis Infectious canine tracheobronchitis Pneumonia and enteritis (secondary pathogen) Bronchopneumonia in immunocompromised (SCID) Mild respiratory disease, enteritis, encephalitis Asymptomatic, or pneumonia (high mortality) Diarrhea Severe respiratory and enteric disease in lambs None to mild respiratory disease |

|

Siadenovirus |

Frog siadenovirus A Raptor siadenovirus A Psittacine adenovirus 2 Budgerigar adenovirus 1 Gouldian finch adenovirus 1 Silawesi tortoise adenovirus 1 Turkey adenovirus 3 |

Hemorrhagic enteritis (turkeys), marble spleen (pheasants), avian adenovirus splenomegaly (broiler chickens) |

Table 1. Adenoviruses of importance in animal species

Contributing Institution:

Iowa State University

College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Ames, IA 50010-1250

https://vetmed.iastate.edu/vpath

JPC Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, multifocal to

coalescing, chronic, moderate with fibrosis and numerous hepatocellular intranuclear

viral inclusions

JPC Comment: The contributors have done an excellent job discussing adenoviral infection in a wide range of species. Adenoviral hepatitis has made a number of appearances in the WSC over the years below. (Table 2).

In addition to the listing of infected lizards mentioned by the contributor, adenoviruses have also been documented in eastern bearded dragons, savannah and emerald monitors, Rankinâs dragon lizard, central netted dragons, western striped tree dragons, green anoles, Jacksonâs and mountain chameleons, , common agamas, and Tokay geckos.10 Most if not all adenoviral infections in lacertids focus primarily on the liver. Clinical signs may range from none to acute CNS signs to chronic wasting and gross findings are usually minimal. Histology in affected livers usually is that of a necrotizing hepatitis, and the biliary epithelium is also affected in some species. In addition to hepatocytes, intranuclear inclusions may be seen in a range of other cells, including enterocytes, endothelial cells, renal tubular epithelium, glomeruli, exocrine pancreas, and oral mucous membrane.10 Proliferative changes have been reported (primarily affecting the tracheal and esophageal mucosa) in Jackson chameleons.10 Coinfections are common, including dependoparvovirus (reported as a hepatic coinfection in bearded dragons with adenovirus)7,10, ranavirus, iridovirus, and gastrointestinal parasites such as coccidia and helminths.10 Nile crocodiles) also have an adenovirus which results in hepatitis as well.7

While adenoviruses are well-known for their disease-causing effects in multiple species, including humans, adenoviruses are also on the forefront of human medicine, especially in the areas of gene therapy and vaccine delivery. As adenovirus DNA does not incorporate into the viral genome during transcription such as say retroviral DNA, they are an ideal vector for the delivery of genes or antigenic materials on a therapeutic basis.13 An issue that faces adenovirus vectors, however, is the prevalence of antibodies to many common human adenoviruses in potential patients (arising from the mild infections of the respiratory, GI, and urinary tracts that adenovirus cause in immunocompetent individuals. The use of adenoviruses linked to animal, but not human, disease (such as chimpanzee adenoviruses) has been proposed to solve this issue, but concern about potential generation of severe cross-species disease has tempered its current usage.13

|

WSC

2018-2019, Conf 21, Case 2 |

Chicken |

|

WSC

2018-2019, Conf 16, Case 1 |

Dog |

|

WSC

2009-2010, Conf 9, Case 3 |

Bearded Dragon |

|

WSC

2007-2008, Conf 23, Case 3 |

Falcon |

|

WSC 1991, Conference 6, Case 2 |

Chimpanzee |

Table 2. Adenoviral hepatitis in the WSC

The moderator reviewed the pertinent gross anatomy of the bearded dragon. The moderator gave a brief discussion of dependoviruses, which often are seen as coinfections with adenovirus, as they âdependâ on the viral machinery of adenoviruses for replication.

References:

1. Bak E-J, Jho Y, Woo G-H. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of a new adenoviral polymerase gene in reptiles in Korea. Arch Virol. 2018: 1-7.

2. Benge SL, Hyndman TH, Funk RS, et al. Identification of helodermatid adenovirus 2 in a captive central bearded dragon (pogona vitticeps), wild gila monsters (heloderma suspectum), and a death adder (acanthophis antarcticus). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2019;50: 238-242.

3. Doneley R, Buckle K, Hulse L. Adenoviral infection in a collection of juvenile inland bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Aust Vet J. 2014;92: 41-45.

4. Fredholm DV, Coleman JK, Childress AL, Wellehan Jr JF. Development and validation of a novel hydrolysis probe real-time polymerase chain reaction for agamid adenovirus 1 in the central bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). J Vet Diang Invest. 2015;27: 249-253.

5. Hallinger MJ, Taubert A, Hermosilla C, Mutschmann F. Captive Agamid lizards in Germany: Prevalence, pathogenicity and therapy of gastrointestinal protozoan and helminth infections. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;63: 74-80.

6. Hyndman TH, Howard JG, Doneley RJ. Adenoviruses in free-ranging Australian bearded dragons (Pogona spp.). Vet Microbio. 2019;234: 72-76.

7. Jacobson ER. Viruses and viral diseases of reptiles. In: Infectious diseases and pathology of reptiles: color atlas and text. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007:395-460.

8. Kim DY, Mitchell MA, Bauer RW, Poston R, Cho D-Y. An outbreak of adenoviral infection in inland bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps) coinfected with dependovirus and coccidial protozoa (Isospora sp.). J Vet Diang Invest. 2002;14: 332-334.

9. Marschang

RE. Viruses infecting reptiles. Viruses. 2011;3: 2087-2126.

10. Orrigi, F. Lacertilia. In In Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J. Pathology of Wildlife

and Zoo Animals. London, UK. Associated Press, pp. 875.

11. Schilliger L, Mentré V, Marschang RE, Nicolier A, Richter B. Triple

infection with agamid adenovirus 1, Encephaliton cuniculi-like microsporidium

and enteric coccidia in a bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). Tierarztl Prax

Ausg K. 2016;5.

12. Schmidt-Ukaj S, Hochleithner M, Richter B, Hochleithner C, Brandstetter D,

Knotek Z. A survey of diseases in captive bearded dragons: a retrospective

study of 529 patients. Vet Med (Praha). 2017;62: 508-515.

13. Tatsia N, Ertl HCJ. Adenoviruses as vaccine vectors. Mol Therap

2004. (10)4: 616-630

14. Wellehan JF, Johnson AJ, Harrach B, et al. Detection and analysis of six

lizard adenoviruses by consensus primer PCR provides further evidence of a

reptilian origin for the atadenoviruses. J Virol. 2004;78: 13366-13369.