Signalment:

Gross Description:

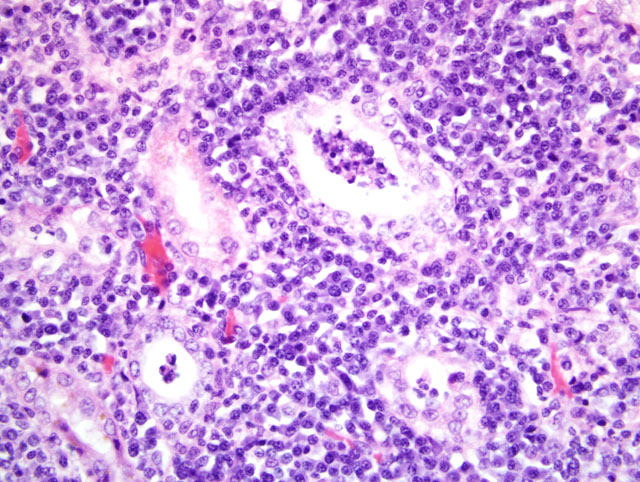

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

| Serology (Texas VMDL) revealed the following titers: | |

| - L. pomona | 12,800 |

| - L. grippotyphosa | 12,800 |

| - L. bratislava | 12,800 |

| - L. hardjo | 3,200 |

| - L. icterohaemorrhagiae | 3,200 |

| - L. canicola | 3,200 |

| PCR of kidney and urine for Leptospira sp. (Texas VMDL) was positive. | |

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Classically, hosts for leptospirosis have been subdivided into primary versus incidental or accidental. Therefore, dogs are regarded as the primary host for Leptospira canicola and accidental hosts for Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae (primary host, rat). In the last 12 years or so, multiple outbreaks of leptospirosis have been attributed to non-canine serovars such as Leptospira grippotyphosa (primary host, vole), Leptospira pomona (primary host, cattle and pig) and Leptospira bratislava (primary reservoir, pig and horse). The dog in the case submitted had high serologic titers to all of the atypical canine serovars. Although it is fun to speculate that Leptospira grippotyphosa is the primary infection and that the other serovars are cross reactions, this is always arrogant speculation and not evidence-based science.

The Leptospira microscopic agglutination test (MAT) is ideally performed on paired sera 3-4 weeks apart, looking for a fourfold rise in antibody titer. This is likely more important with Leptospira canicola, particularly if a dog was previously vaccinated. The high levels seen in this case are more typical of an accidental host with a non-canine serovar. Antibodies are typically first detected 7-10 days after infection. Several other diagnostic techniques were pursued to confirm the diagnosis. PCR of kidney and urine was positive for Leptospira DNA (Texas VMDL). This is a genus-specific result only. Warthin-Starry silver staining was attempted to demonstrate leptospires in tubules and was unsuccessful. Immunohistochemistry was performed (Purdue ADDL) revealing convincing clumped Leptospira antigen in tubular epithelial cells and tubular lumina. This disparity was interpreted as a consequence of lack of viability of the leptospires due to the prolonged postmortem interval. Similarly, dark field microscopy of urine was inconclusive; this test also requires fresh urine to observe normal leptospires. Fluorescent anybody testing of centrifuged urine sediment also has the advantage of not requiring leptospires to be viable. Researchers at Mississippi State University have identified transcriptional regulator genes that are present in pathogenic Leptospira strains and absent in non-pathogenic strains. PCR primers have been developed that conceivably can easily separate pathogenic from nonpathogenic Leptospira.(4)

The stratified appearance of an intense white band in the inner cortex and zones of hemorrhage and necrosis in the medulla are a classic pattern of acute leptospirosis culminating in acute renal failure in dogs. A series of these cases was studied retrospectively and prospectively and determined to have a unique ultrasonographic pattern strongly suggestive of acute leptospirosis by Lisa Forrest and colleagues at the University of Wisconsin.(1) When dogs are presented in acute renal failure to veterinarians, initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy requires timely decisions, and ultrasonography was determined to be a strongly suggestive finding for identifying leptospirosis due to atypical serovars. Otherwise, many of these dogs are euthanized with the presumption of chronic renal failure.

The classification of Leptospira has recently been changed.(3) Previously, one pathogenic species (Leptospira interrogans) and one nonpathogenic species (Leptospira biflexa) were recognized. These two species were subdivided into serovars-�-�200 in Leptospira interrogans and around 60 in Leptospira biflexa. Based on DNA hybridization Leptospira has been reclassified into 13 genomospecies. Since both pathogenic and nonpathogenic species may occur in a single genomospecies, the utility of this scheme for veterinarians, microbiologists, pathologists and others dealing with the disease has not been clarified. Therefore, serovars and serogroups will likely persist in diagnostic reports.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

| Leptospira Serovars, Maintenance Hosts, and Disease | ||

|---|---|---|

| canicola | Dog | Dog: primarily renal disease; now rare due to vaccination |

| grippotyphosa | Raccoon, skunk, rodent | Dog: renal and hepatic disease; increasingly important |

| Horse: abortion, premature foaling | ||

| icterohemorrhagiae | Rat | Dog: primarily hepatic disease; hyperacute disease in puppies; now rare due to vaccination |

| bratislava | Pig, horse, +/- dog | Dog: nephritis and abortion |

| Pig: abortion, small litters of weak piglets | ||

| Horse: abortion, premature foaling | ||

| pomona type kennewicki | Pig | Dog: renal and hepatic disease; increasingly important |

| Pig: abortion, small litters of weak piglets | ||

Cattle:

| ||

Horse:

| ||

| Pinnipeds: abortions, hemorrhagic syndromes in fetuses and neonates, interstitial nephritis and glomerulonephritis, hepatic necrosis | ||

| autumnalis | Rodents | Dog: renal and hepatic disease; increasingly important |

| Pig: infertility syndrome ("repeat breeder") | ||

| hardjo type hardjobovis (North America) | Cattle, sheep | Cattle: chronic form; abortion, stillbirth, or premature weak calves |

Sheep:

| ||

| hardjo type hardjoprajitno (Europe) | Cattle | Cattle:

|

Sheep:

| ||

| ballum | Mouse | Hamster: severe hemolysis, icterus, hemoglobinuria, nephritis, hepatitis |

References:

2. Greene CE, Sykes JE, Brown CA, Hartmann K: Leptospirosis. In: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, ed. Greene CE, 3rd ed., pp. 402-417. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2006

3. Levett PN: Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 14:296-326, 2001

4. Liu D, Lawrence ML, Austin FW, Ainsworth AJ, Pace LW. PCR detection of pathogenic Leptospira genomospecies targeting putative transcriptional regulator genes. Can J Microbiol 52:272-277, 2006

5. Newman SJ, Confer AW, Panciera RJ: Urinary system. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, ed. McGavin MD, Zachary JF, 4th ed., pp. 658-662. Mosby Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2007

6. Percy DH, Barthold SW: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, 3rd ed., pp. 65, 152, 192, 211. Blackwell, Ames, IA, 2007

7. Prescot JF: Leptospirosis. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 481-490. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

8. Radostits OM, Gay CC, Blood DC, Hinchcliff KW: Diseases caused by Leptospira spp. In: Veterinary Medicine: A textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses, eds. Radostits OM, Gay CC, Blood DC, Hinchcliff KW, 9th ed., pp. 971-982. W.B. Saunders, London, England, 2000

9. Szeredi L, Haake DA. Immunohistochemical identification and pathologic findings in natural cases of equine abortion caused by leptospiral infection. Vet Pathol 43:755-761, 2006