WSC 2023-2024, Conference 23, Case 3

Signalment:

4-year-old male African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris).

History:

This hedgehog presented to the teaching hospital for severe dental disease. A submandibular mass was noted during examination. Under anesthesia for a dental procedure, the animal decompensated, developing cyanosis. The patient showed clinical improvement when naloxone was administered and had a prolonged recovery from anesthesia. The patient was mobile and eating following recovery, but acutely decompensated 1.5 hours later. Resuscitation was attempted but was unsuccessful.

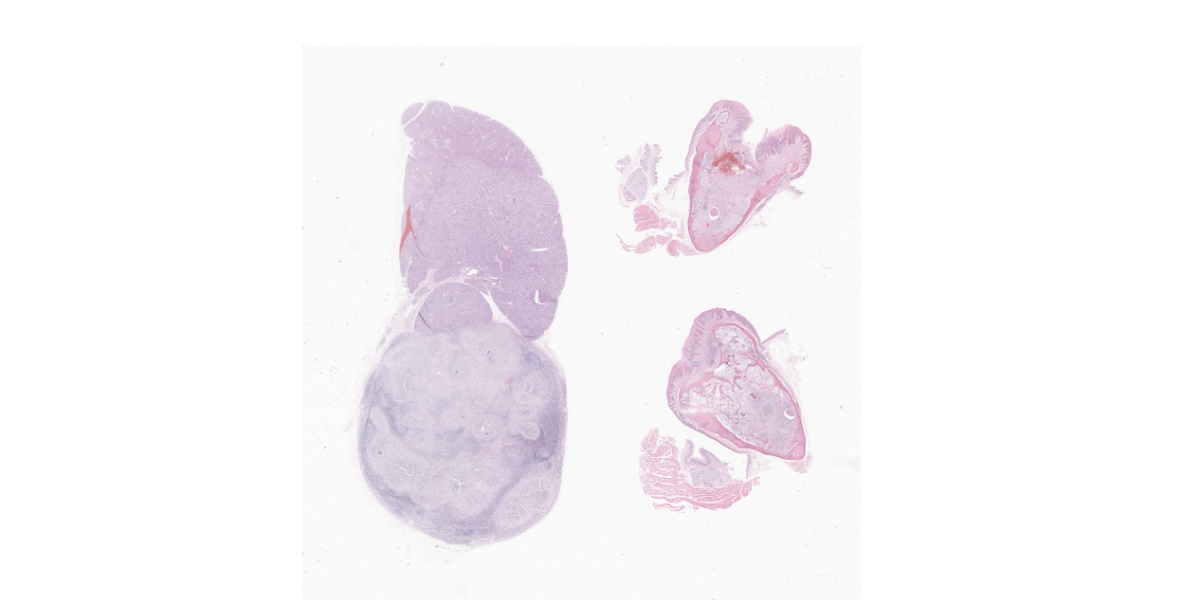

Gross Pathology:

The hedgehog was in good body condition. There was slight deviation of the muzzle to the right. Only one tooth (the lower right first incisor) remained in the dental arcade and was easily removed with traction. Both mandibles were mildly thickened and slightly irregular with smooth undulations noted in the gingiva.

Mild hemorrhage was present near the right submandibular salivary gland and a 0.5 cm pale nodule (presumed enlarged lymph node) was associated with the gland. Dark pink discoloration and consolidation of the lung was present bilaterally and scattered, small (1 mm) white foci were noted in the affected regions. The heart weighed 1.8 g (0.56% of the total body weight).

Laboratory Results:

Light growth of Neisseria animaloris was isolated from the right submandibular lymph node (aerobic culture; species identified using MALDI-TOF). No microbial growth was isolated from this organ on anaerobic culture.

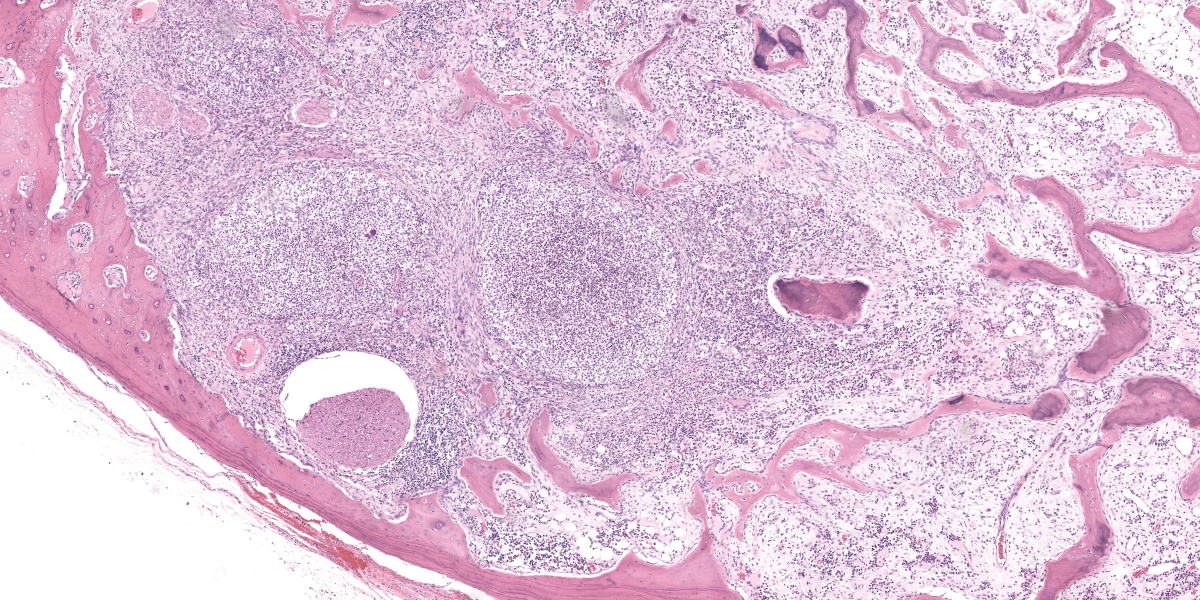

Microscopic Description:

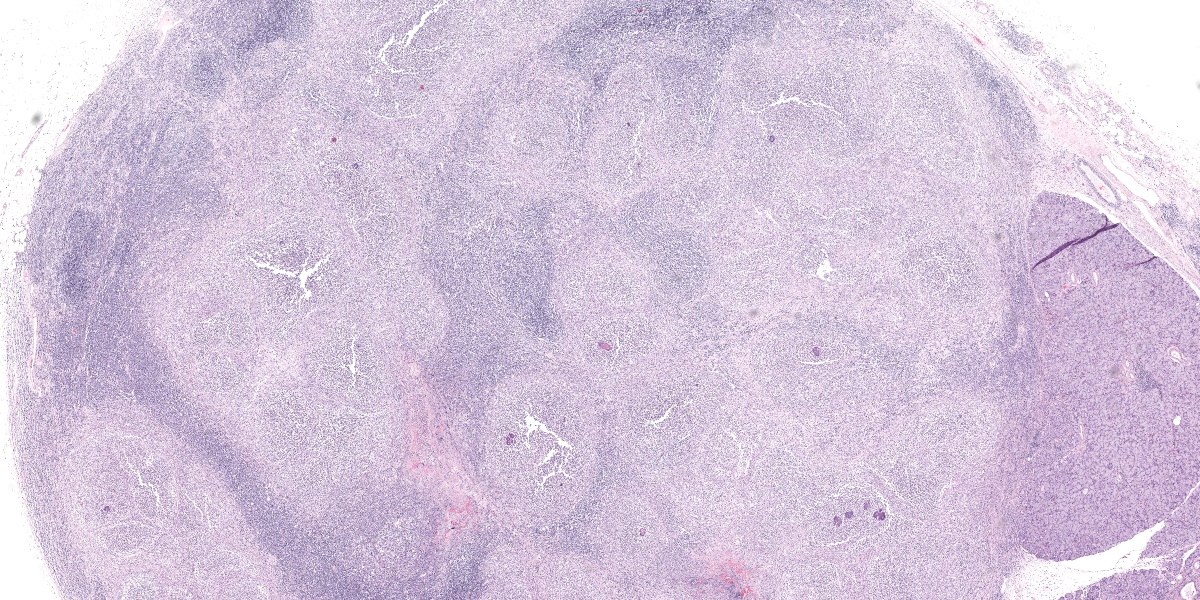

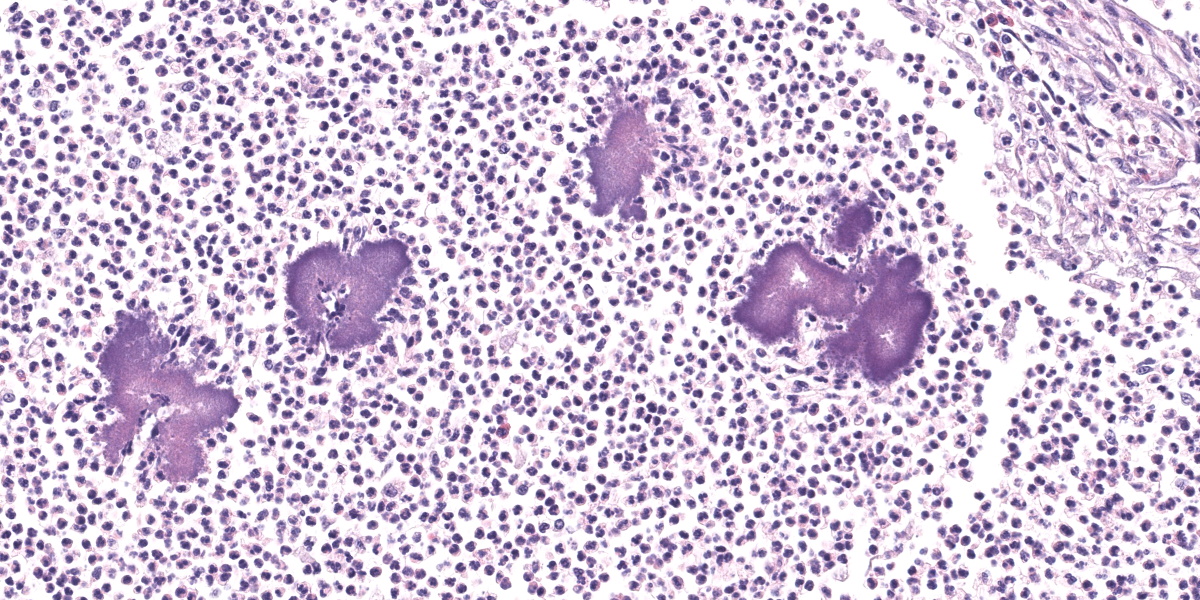

Submandibular lymph node: Large coalescing regions of pallor obscure the normal architecture of the enlarged lymph node. Areas of pallor consist of multifocal to coalescing nodular aggregates of mostly neutrophils with fewer epithelioid macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells. At the center of the infiltrates are frequent deposits of basophilic bodies occasionally with peripheralized eosinophilic acellular material (Splendore-Hoeppli reaction). Small, non-filamentous, coccoid Gram-negative bacteria are identified at the center of these deposits using a Gram stain. At the periphery of the cell aggregates, there are thin concentric bands of connective tissue and moderate eosinophilic infiltrates. A few small scattered secondary lymphoid follicles are separated by sheet like infiltrates of plasma cells.

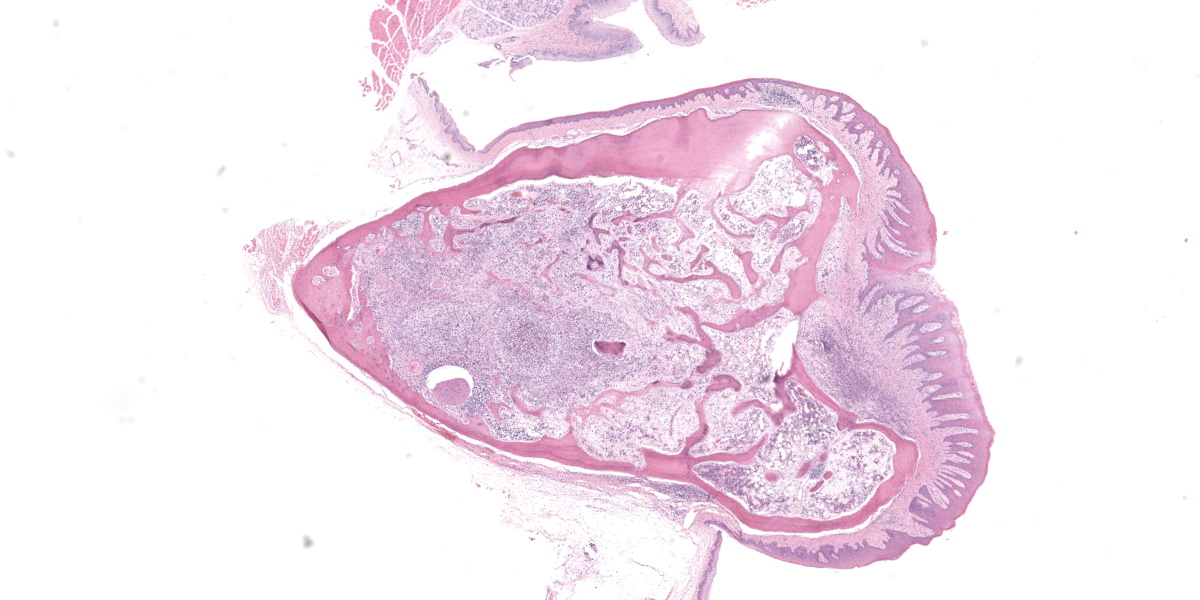

Jaw: There are multifocal to coalescing regions of increased cellularity and loss of trabecular bone within the mandible. Cellular infiltrates consist of nodular aggregates of mostly neutrophils with fewer epithelioid macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and rare eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells. At the center of the infiltrates are rare radiating deposits of basophilic material with peripheralized eosinophilic acellular material (Splendore-Hoeppli reaction). At the periphery of the cell aggregates, there are thin concentric bands of connective tissue, plasma cell infiltrates, and focal hemorrhage. Remodeling of the surrounding bone with new woven bone formation is evident. The gingival mucosal epithelium is hyperplastic, eroded, and infiltrated by neutrophils and fewer eosinophils.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Submandibular lymph node: Lymphadenitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, chronic, severe, with intralesional Gram-negative bacteria and Splendore-Hoeppli reaction.

- Jaw: Osteomyelitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, chronic, severe, with intralesional bacteria and Splendore-Hoeppli reaction.

Contributor’s Comment:

This hedgehog had a history of significant dental disease resulting in loss/removal of most of the teeth. Dental diseases, including gingivitis, periodontitis, tooth fracture, tooth loss, excess dental wear, dental abscesses, and even oral osteomyelitis are common in this species.1,6 Mandibular osteomyelitis was marked and was accompanied by a similar reaction in the draining lymph node and in the lung (not included in the submission). Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon was evident within the lesions. This nonspecific reaction is thought to reflect the deposition of antigen-antibody complexes and inflammatory cell products/debris, and occurs around clusters of microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, or biologically inert substances.5 Genera of bacteria that are commonly associated with this reaction include Actinomyces, Nocardia, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Proteus, Pseudomonas, and Escherichia coli.5

Mandibular osteomyelitis is not uncommon as a cause of morbidity in pet and wild hedgehogs and may occur secondary to periodontitis, but there are few studies confirming the etiology of these lesions.6,7,10 In mortality studies on European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus), mandibular abscesses and botryomycosis were detected in 23% of evaluated animals but these lesions were reportedly confined to the submandibular soft tissues, and they were not evaluated microbiologically.10

The lesion in this hedgehog has a similar appearance to “lumpy jaw” resulting from Actinomyces bovis infections in cattle, and a similar lesion has been described in a captive African pygmy hedgehog infected with Actinomyces naeslundii.7,8 Like the reported case, there was involvement of the draining lymph node and the lung in this hedgehog. However, the bacterium in the submitted case was Gram-negative and pure growth of Neisseria animaloris was isolated from the lesion.

Neisseria animaloris is a common inhabitant of the oral cavity of animals (particularly cats and dogs) and may cause systemic infections in humans and animals, often as a result of a bite wound.2,3,4 These infections can result in localized or systemic pyogranulomatous lesions which exhibit Splendore-Hoeppli reaction around the Gram-negative diplococci.2,3 Given the zoonotic potential of this bacterium, it would be interesting to know if this organism is part of the normal oral microbiome of the African pygmy hedgehog.3,4 If so, this may add to the growing list of known zoonotic bacterial pathogens potentially carried by captive and wild hedgehogs, which already includes Leptospira spp., Salmonella spp., Mycobacterium spp, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus spp.9

While the oral lesions in this case were considered significant, cyanosis during anesthesia and the subsequent death of this patient was most likely due to heart failure resulting from cardiomyopathy.

Contributing Institution:

Atlantic Veterinary College

University of Prince Edward Island

Department of Pathology and Microbiology

https://www.upei.ca/avc/pathology-and-microbiology

JPC Diagnoses:

1. Lymph node: Lymphadenitis, pyogranulomatous, diffuse, marked, with Splendore-Hoeppli material and colonies of cocci.

2. Mandible: Osteomyelitis, pyogranulomatous, diffuse, marked, with pathologic fracture, ulcerative and lymphoplasmacytic gingivitis, Splendore-Hoeppli material, and colonies of cocci.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent case of mandibular osteomyelitis in an African hedgehog which highlights to tendency of this species to develop pathology in the oral cavity. African hedgehogs are short-lived exotic pets with a life expectancy of 4 to 6 years and are considered geriatric at 3-5 years of age.6 They are particularly prone to neoplasia, even in early age, and are susceptible to age-related cardiovascular, renal, and periodontal disease.6

Hedghogs are particularly prone to dental disease, including gingivitis, dental calculus, periodontitis, and tooth loss.6 Periodontal disease may be preventable with proper diet, with dry kibble and raw fruits and vegetables thought to promote periodontal health versus moist or canned foods.6 Hedgehog oral disease of any variety may be accompanied by florid gingival hyperplasia that can be difficult to distinguish from neoplasia grossly. Clinical signs include reduced food intake or changes in food preferences, anorexia, weight loss, dysphagia, drooling, hemorrhage, and halitosis.6 Gross findings may include gingival swelling and inflammation, loose or missing teeth, swelling of the face, and abnormal facial bone positioning.6

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common tumor of the African hedgehog digestive system and is reported to be the most common overall hedgehog neoplasia.6 Oral SCC has been reported in hedgehogs as young as 1 year old and as old as 6 years. Diagnosis can be difficult without histology as the cytologic appearance of oral SCC needle aspirates can look very similar to early stage periodontal disease, and distinguishing the two conditions on cytology alone is often impossible.6 Surgical excision of oral tumors, including SCC, is often incomplete and oral tumors frequently recur; prognosis is therefore poor for oral neoplasia, making differentiating between oral neoplasia and periodontal disease, which often responds well to targeted antimicrobial therapy, of prime prognostic importance.6

The aged hedgehog in this case read the textbook, with severe oral and cardiovascular disease at the time of death. Conference participants noted the large peripheral nerve surrounded by the intense inflammatory milieu and spared a thought for what must have been an extremely painful condition for this hedgie. The moderator encouraged participants to evaluate bone at the subgross level where symmetry is most easily assessed. Subgross evaluation in this case reveals an extremely unsymmetrical mandible, which is an initial indication of bone involvement. The moderator also noted that polarization at subgross magnification can reveal which bone is well-organized parent bone and which is reactive. Subgross evaluation also reveals impressive gingival ulceration, which presumably provided an excellent portal for Neisseria animaloris to enter the deeper tissue of the oral cavity and provoke the incredible inflammatory response captured on this delightful slide.

Conference participants noted the somewhat unexpected abundance of eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate, which some partipants noted was an occasional feature of inflammation in hedgehogs. This lead to a brief discussion of eosinophilic leukemia, a myelogenous leukemia of hedgehogs that appears in middle age and carries a grave prognosis.

Participants felt that the morphologic diagnosis should include elements critical to the pathogenesis, which in this case is presumed to begin with ulcerative gingivitis, bacterial invasion, and pyogranulomatous inflammation. Participants also interpreted the appearance of the submucosal bone fragments under polarized light as pathologic fracture, which all thought warranted mention in the morphologic diagnosis.

References:

- Chaprazov T, Dimitrov R, Yovcheva KS, Uzunova K. Oral and dental disorders in pet hedgehogs. Turk J Vet Anim Sci. 2014; 38(1):1-6.

- Foster G, Whatmore AM, Dagleish MP, et al. Forensic microbiology reveals that Neisseria animaloris infections in harbour porpoises follow traumatic injuries by grey seals. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):14338.

- Helmig KC, Anderson MS, Byrd TF, Aubin-Lemay C, Moneim MS. A rare case of Neisseria animaloris hand infection and associated nonhealing wound. J Hand Surg Glob Online 2020;2(2):113-115.

- Heydecke A, Andersson B, Holmdahl T, Melhus A. Human wound infections caused by Neisseria animaloris and Neisseria zoodegmatis, former CDC Group EF-4a and EF-4b. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2013;3:1-5.

- Hussein MR. Mucocutaenous Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon. J Cutan Pathol 2008;35(11):979-988.

- Johnson DH. Geriatric Hedgehogs. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2020; 23(3):615-637.

- Martinez LS, Juan-Salles C, Cucchi-Stefanoni K, Garner MM. Actinomyces naeslundii infection in an African hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris) with mandibular osteomyelitis and cellulitis. Vet Rec 2005; 157(15):450-451.

- Olson EJ, Dykstra JA, Armstrong AR, Carlson CS. Bones, joints, tendons and ligaments. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2022:1037-1490.

- Ruszkowski JJ, Hetman M, Turlewicz-Podbielska H, Pomorska-Mól M. Hedgehogs as a potential source of zoonotic pathogens-a review and an update of knowledge. Animals (Basel) 2021;11(6): 1754.

- Zacharopoulou M, Guillaume E, Coupez G, Bleuart C, Le Loc’h G, Gaide N. Causes of mortality and pathological findings in European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) admitted to a wildlife care centre in southwestern France from 2019 to 2020. J Comp Pathol. 2022;190:19-29.