Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

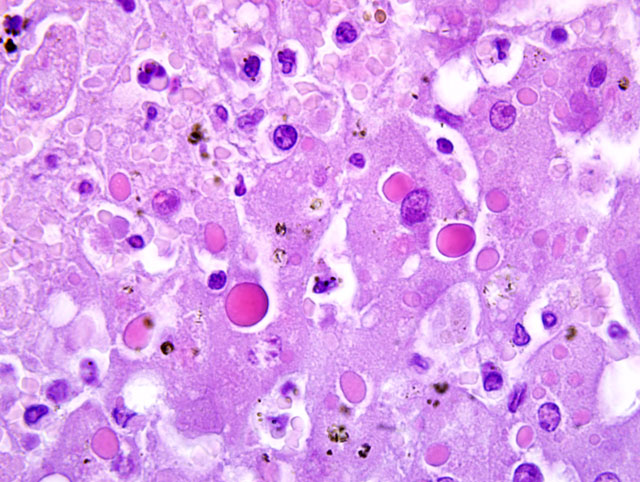

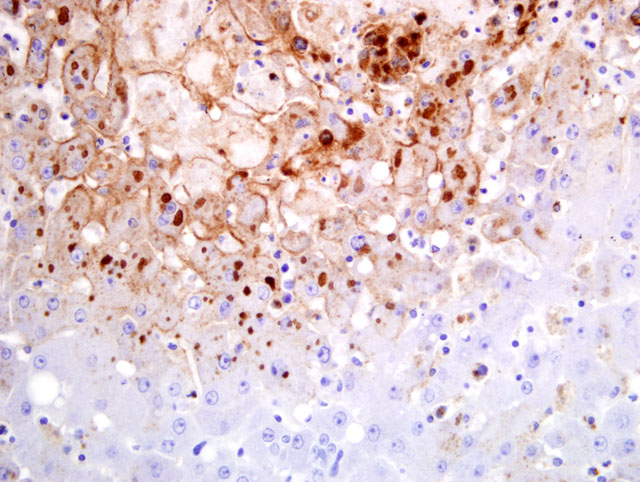

Liver: Multifocally to coalescing there are randomly distributed foci of hepatocellular degeneration and necrosis, characterized by hypereosinophilia, loss of cellular detail, cellular debris, and pyknotic as well as karyorrhectic nuclei (coagulative necrosis). Foci vary in size from 40 to 200 μm; in some locations only single hepatocytes are affected. In less affected areas, hepatocytes are swollen, have pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and swollen nuclei (degeneration). Centrally in the necrotic zone there is extravasation of blood cells (acute hemorrhage) admixed with fibrin and degenerated inflammatory cells. Within the cytoplasm of necrotic cells, degenerating cells and unaltered hepatocytes there are up to five, oval or round, bright eosinophilic inclusion bodies (5-10 μm in size). Additionally, there is mild portal fibrosis and bile duct proliferation. There is a mild portal infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Single hepatocytes show cytoplasmic vacuolization (fatty change) and there is a mild intracanalicular cholestasis.Â

Spleen and lymph node lesions (slides not submitted) were characterized by necrotizing inflammation, and cytoplasmic inclusion bodies were detectable occasionally. Skin lesions (slides not submitted) showed hyperplasia and degeneration of epithelial cells (ballooning degeneration) with acantholysis. Within the subcutaneous tissue of the neck there was marked edema and necrosuppurative cellulitis and necrotizing lymphadenitis of retropharyngeal lymph nodes.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, random, subacute, severe, with intralesional hemorrhage and numerous intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, banded mongoose, Mungos mungo.Â

Etiology: Consistent with systemic cowpoxvirus infection.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

There are several reports on cowpox virus infection in zoo animals. Reports of lethal poxvirus infections in elephants (4) and fatal cases in felids (1,8) can be found in the literature. Felids usually develop a mild dermal or a fatal pulmonary course of the disease. Necrotizing hepatitis due to cowpox virus is rare in felids; however, cases have been described in lions and cheetahs.(8)

In the banded mongooses the most severe lesions were necrotizing hepatitis, splenitis and lymphadenitis with occurrence of characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies. In contrast to cases of cowpox virus in other members of the suborder Feliformia, the lungs were unaltered. The etiologic diagnosis was confirmed by cell culture, electron microscopy, PCR and sequencing. Wild rodents may have served as reservoir and vector in our cases. This hypothesis was supported by observation of poxvirus lesions in a captured rat in the surrounding of the outdoor enclosure.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

While many members of the Poxviridae family cause only localized cutaneous disease, the following characteristically produce systemic disease, which may be severe: Sheeppox virus, Ectromelia virus, Monkeypox virus, and Variola virus.(5) Conference participants discussed these and other poxviruses of veterinary importance, which are summarized by genus as follows:

- Avipoxvirus: 10 species, including Fowlpox virus

- Capripoxvirus: Goatpox virus, Lumpy skin disease virus, Sheeppox virus

- Cervidpoxvirus: Deerpox virus W-848-83

- Leporipoxvirus: Myxoma virus, Rabbit (Shope) fibroma virus, Squirrel fibroma virus

- Molluscipoxvirus: Molluscum contagiosum virus

- Orthopoxvirus: Camelpox virus; Cowpox virus; Ectromelia virus; Monkeypox virus; Vaccinia virus (buffalopox virus, rabbit pox virus); Variola virus

- Parapoxvirus: Bovine papular stomatitis virus; Orf virus; Parapoxvirus of red deer in New Zealand; Pseudocowpox virus

- Suipoxvirus: Swinepox virus

- Yatapoxvirus: Tanapox virus; Yaba monkey tumor virus

- Unassigned: Squirrel poxvirus (5,6)

Typical poxviral lesions are both proliferative and necrotizing. As poxviruses are epitheliotropic, replication within cells causes degeneration (i.e. ballooning degeneration) and necrosis, which is further exacerbated by ischemia when the virus replicates in endothelial cells and causes vascular damage. Several virulence factors may account for the ability of poxviruses to induce proliferation, including a gene whose product resembles epidermal growth factor.(5)

Unlike other DNA viruses, poxviruses produce intracytoplasmic, rather than intranuclear inclusion bodies. All poxviruses produce small, basophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, designated type B or Guarnieris bodies, early in the replication cycle. These represent the actual sites of virus replication. The numerous, large, prominent, eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies noted in this case are designated type A or acidophilic-type inclusions (ATI), and they are produced later in the replication cycle. In humans, type A inclusions are diagnostically useful, because they are only associated with certain poxviruses (e.g. Cowpox and Ectromelia virus, but not Monkeypox, Variola, or Vaccinia virus). Capripoxviruses generally produce type A inclusions; the large inclusions in Avipoxvirus infections are known as Bollinger bodies and they contain smaller Borrel bodies representing virus particles.(12)

References:

2. Campe H, Zimmermann P, Glos K, Bayer M, Bergemann H, Dreweck C, Graf P, Weber BK, Meyer H, B+�-+ttner M, Busch U, Sing A: Cowpox virus transmission from pet rats to humans, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 15(5):777-80, 2009

3. Chantrey J, Meyer H, Baxby D, Begon M, Bown KJ, Hazel SM, Jones T, Montgomery WI, Bennett M: Cowpox: reservoir hosts and geographic range. Epidemiol Infect 122(3):455-460, 1999

4. Essbauer S, Meyer H, Kaaden OR, Pfeffer M: Recent cases in the German poxvirus consulting laboratory. Revue Med Vet 153:635-642, 2002

5. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich PM: Skin and appendages. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 664-674. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

6. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (Internet): Virus taxonomy. Available from: http://www.ictvonline.org , 2008

7. Kurth A, Wibbelt G, Gerber HP, Petschaelis A, Pauli G, Nitsche A: Rat-to-elephant-to-human transmission of Cowpox virus. Emerg Infect Dis 14(4):670-671, 2008

8. Marennikova SS, Maltseva NN, Korneeva VI, Garanina N: Outbreak of pox disease among carnivora (felidae) and edentata. J Infect Dis 135:358-366, 1977

9. Ninove L, Domart Y, Vervel C, Voinot C, Salez N, Raoult D, Meyer H, Capek I, Zandotti C, Charrel RN: Cowpox virus transmission from pet rats to humans, France. Emerg Infect Dis 15(5):781-784, 2009

10. Nitsche A, Kurth A, Pauli G: Viremia in human Cowpox virus infection. J Clin Virol 40(2):160-162, 2007

11. Pahlitzsch R, Hammarin AL, Widell A: A case of facial cellulitis and necrotizing lymphadenitis due to cowpox virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 43(6):737-742, 2006

12. Pfeffer M, Meyer H: Poxvirus diagnostics. In: Poxviruses, eds. Mercer AA, Schmidt A, Weber O, p. 359. Birkh+�-�user Verlag, Basel, Switzerland, 2007

13. Schulze C, Alex M, Schirrmeier H, Hlinak A, Engelhardt A, Koschinski B, Beyreiss B, Hoffmann M, Czerny CP: Generalized fatal Cowpox virus infection in a cat with transmission to a human contact case. Zoonoses Public Health 54(1):31-37, 2007

14. Wolfs TF, Wagenaar JA, Niesters HG, Osterhaus AD: Rat-to-human transmission of Cowpox infection. Emerg Infect Dis 8(12):1495-1496, 2002