Signalment:

Gross Description:

The peritoneal cavity contained 20 ml of dark red watery fluid. The intestines were segmentally filled with dark brown, slightly flocculent, viscous digesta. Mesenteric lymph nodes were dark red and moderately enlarged (up to 1.2 cm in diameter). Hepatic parenchyma and brain tissues were grossly unremarkable.

Histopathologic Description:

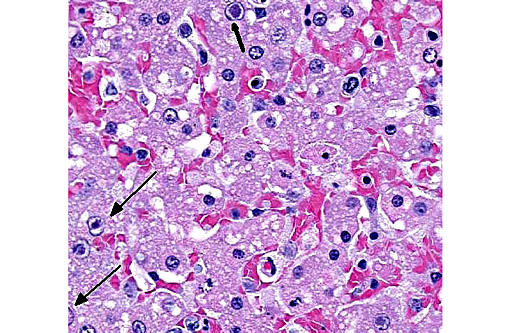

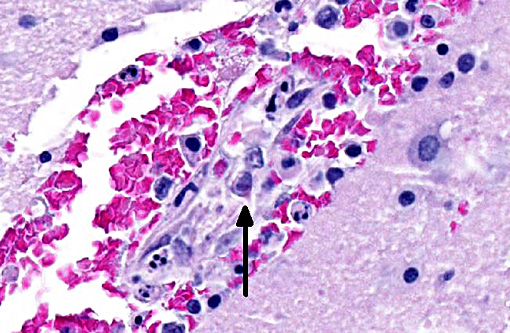

Brain: Multifocally, extending from the caudal brainstem to the thalamus, hypothalamus and basal nuclei, endothelial cells in blood vessels are frequently necrotic and occasionally contain similar intranuclear viral inclusion bodies. Neighboring endothelial cells are enlarged (reactive). The tunica media is often hypereosinophilic and disorganized, and mixed with pyknotic nuclear debris (fibrinoid necrosis). In the surrounding blood vessels Virchow-Robins spaces contain small numbers of lymphocytes, macrophages, necrotic cells and extravasated erythrocytes (hemorrhage). Similar but less extensive lesions are observed in meninges and cerebral cortex. The cerebellum was not affected.

Other significant histologic changes were identified in the following organs:

Thymus (hemorrhage and lymphocytolysis), spleen, Peyers patches and lymph nodes (massive lymphoid and red pulp necrosis with very few inclusions), kidney (inclusions in glomeruli and vascular endothelial cells), heart (rare endothelial inclusions).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, centrilobular to mild zonal, severe, acute with hepatocellular and endothelial intranuclear viral inclusion bodies.

Brain: Encephalitis, multifocal, moderate, acute, with vasculitis, hemorrhages and endothelial intranuclear viral inclusion bodies.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The pathogenesis of ICH begins with infection with CAV-1 after exposure to infectious saliva, feces, urine, or respiratory secretions. The virus initially localizes in tonsil and regional lymph nodes, finally spreading to the bloodstream approximately four days post infection. Primary targets of circulating CAV-1 include hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, glomerular endothelium, and uvea. Any vascular endothelium is susceptible, causing multifocal petechial hemorrhage, and severe widespread endothelial damage leads to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).(7) Although adenovirus was first identified after noting viral inclusions in the brains of foxes with encephalitis, the CNS form is rare. Adenoviral tropism for the CNS has been suggested to be related to viral strain differences.(4)

The earliest clinical sign of ICH is a fever followed by tonsillar enlargement, depression, anorexia, tachycardia, tachypnea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain/distension (due to fluid accumulation and hepatic enlargement), and hemorrhage if liver damage is severe or endothelial damage is widespread. Neurologic signs (ataxia, hypersalivation, and seizures) may occur if there is CNS involvement. If the animal does not die from severe hepatic failure or DIC, approximately 7-14 days post infection, corneal edema (the classic blue eye lesion)(12) and azotemia, hematuria, and proteinuria (secondary to glomerulonephritis) are possible. As was seen in this case, sudden death with no previous clinical signs is possible when CNS infection occurs.(14)

Grossly, hepatic lesions typical of adenoviral infection (swollen mottled liver with gallbladder edema)(5,7) were not noted in this case. However, histologic lesions of multifocal hepatic necrosis, combined with striking intranuclear inclusions in hepatocytes and vascular endothelial cells in the liver and brain suggest etiology consistent with canine adenovirus type 1 (infectious canine hepatitis/CAV-1).

Histologically, typical lesions usually consist of centrilobular to midzonal hepatic necrosis with general sparing of periportal hepatocytes. Cowdry type A inclusions (marginated chromatin and clear halo around the inclusion) are seen in Kupffer cells, hepatocytes, and affected vascular endothelium. Lymphoid organs may be congested with necrosis of lymphoid follicles and intranuclear inclusions in vascular endothelium and histiocytes can be seen. Inclusions may also be found in glomerular or tubular renal epithelium, and central nervous system (CNS) vascular endothelium. Within the CNS, multifocal neuropil hemorrhages, perivascular accumulations of mononuclear cells, mixed with hemorrhage and occasionally fibrin, and intranuclear inclusions in vascular endothelial cells are evident, typically throughout the brainstem and caudate nuclei, often sparing the cerebral and cerebellar cortices.(14) Interestingly, in this case, lesions are noted extending into the cerebral cortex and meninges. Lesions in other organs are typically secondary to vascular endothelial damage and may consist of vascular necrosis, intravascular fibrin thrombi, hemorrhage, and edema.(7,13)

Adenoviral serotypes inducing disease in canines are from the family Mastadenovirus and include CAV-1, which causes the disease known as infectious canine hepatitis (ICH), and CAV-2, which is essential for the development of infectious tracheobronchitis (ITB).(7) Other adenovirus families include Aviadenovirus (avian strains) and Atadenovirus (mammalian, avian, and some reptilian strains). Adenoviruses are typically host specific and produce multiple notable diseases (Table 1, chelonians, amphibians and fish not included). Typically, most adenoviral infections are subclinical, with serious illness only in young or immunocompromised individuals.(7)

Table 1- Most important adenoviruses, affected species and major pathologic lesions

| Species Affected | Serotypes involved /Disease Name | Major Pathologic Findings | |

| Mastadenoviridae | |||

| Canine Ursidae | CAV-1 Infectious Canine Hepatitis | Intranuclear and intraepithelial inclusions in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, endothelium and mononuclear cells with secondary necrosis | |

| CAV-2 Upper respiratory disease conjunctivitis | Important initiator of infectious tracheobronchitis (Kennel Cough) | ||

| Feline | Rare, subclinical disease, only 1 confirmed fatal case | ||

| Bovine | BADV 3,4,10 | Sporadic enteric disease in 1-8 week old calves, tropism for vascular endothelium, lesions are secondary to thrombosis and ischemia | |

| Porcine | PAdV-4- most common in Europe and North America | Typically non-clinical illness, may see pneumonia and enteritis, inclusions are in enterocytes- may be seen in non-clinically affected piglets | |

| Equine | EAdV-1 (worldwide) | May cause pneumonia in SCID (Arabian) foals with intranuclear inclusions in alveolar epithelium, +/- pancreatic degeneration and necrosis with inclusions in pancreatic ducts | |

| EAdV-2 (Australia) | Diarrhea | ||

| Ovine Caprine | OAdV 1-3 GAdV-2 | Mild respiratory and GI disease in lambs and kids, inclusions within lamina propria in lambs, in endothelial cells in kids | |

| Humans | Several strains | Respiratory disease and keratoconjunctivitis | |

| Hamsters | Hamster strains | Enteric disease in less than 4 week old animals Intranuclear inclusions in intestinal epithelium. Experimentally transmitted adenoviruses from other species can induce neoplasia | |

| Aviadenovirus | |||

| Group I | Chickens Turkeys Geese Ducks Kestrel Pigeons | Inclusion Body Hepatitis | Vertically transmitted, hepatocellular hemorrhage and necrosis with intranuclear hepatocellular inclusions, may also see necrotizing pancreatitis with intranuclear inclusions |

| Northern Virginia Quail | Quail Bronchitis | Necrotizing tracheitis, proliferative and necrotizing bronchitis and pneumonia with basophilic intranuclear inclusion in tracheal epithelium | |

| Chickens Quail | Inclusion Body Ventriculitis | ||

| Group II | Turkey gallinaceous birds psittacine | Turkey Hemorrhagic Enteritis | Fibrino-necrotic membranes lining small intestine, intranuclear inclusions in lymphoblasts and macrophages in spleen, and small intestine lamina propria |

| Pheasant | Marble Spleen Disease | Enlarged mottled spleen, congested and edematous lungs, splenic necrosis with large intranuclear inclusions | |

| Chicken | group II splenomegaly virus | Usually causes no mortality. Lesions include splenic reticuloendothelial cell hyperplasia with intranuclear inclusions | |

| Atadenovirus | |||

| Group III | Chickens Ducks | Egg Drop Syndrome | Principle site of virus replication is pouch shell gland, if infection occurs before sexual maturity; virus is latent until maturity occurs. Loss of shell color, thin shelled eggs |

| Bovine | BAdV-5, 6, 7, 8 | Enteric disease | |

| Ovine Caprine | OAD -D GAdV-1 | Enteric disease | |

| Possums | PAdV- 1 | Typically non clinical illness, interest in utilizing virus as a method to control populations as a vector for contraceptive antigens | |

| Squamatids (lizards and snakes) | Agamid AdV-1 (Bearded Dragons), SnAdV-1,2, (snakes), Eublepharid AdV-1 (geckos), Helodermatid AdV-1(gila monsters) | Hepatocellular necrosis with Intranuclear inclusions in hepatocytes. Inclusions also possible in enterocytes, renal epithelium, lung epithelium, myocardial endothelium, glial cells and brain endothelium | |

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Degeneration and necrosis, centrilobular to midzonal, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with numerous hepatocyte and endothelial intranuclear viral inclusions.

Cerebrum and thalamus: Vasculitis, necrotizing, diffuse, moderate, with hemorrhage, edema, and numerous endothelial intranuclear viral inclusions.

Conference Comment:

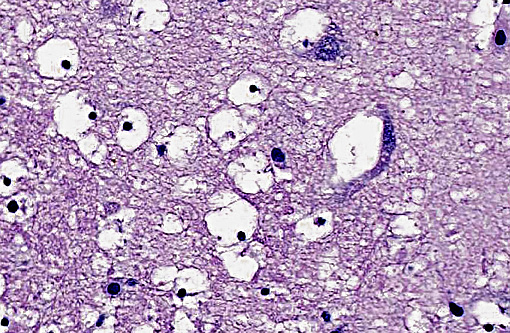

The brain lesions in this case appear to be most severe in the thalamus, where prominent cytotoxic edema of oligodendroglia is evident. Cytotoxic edema occurs due to altered cellular metabolism, often caused by ischemia, and presents as intracellular fluid accumulation. Cells of the CNS vary in their susceptibility to ischemic injury. Neurons are the most sensitive, with oligodendroglia, astrocytes, microglia, and endothelium following in decreasing order.(15) It is curious in this case that neurons are much less severely affected than oligodendroglia, which may allude to irregular or incomplete ischemic damage in this case. Other types of edema that occur within the CNS include vasogenic due to vascular injury, and hydrostatic from elevated pressure, which both results in extracellular fluid accumulation. Also hypo-osmotic edema from plasma microenvironment imbalances can cause both extracellular and intracellular fluid accumulation.(13)

References:

1. Appel, M. et al. "Pathogenicity of low-virulence strains of two canine adenovirus types." American journal of veterinary research 34.4 (1973):543-550.

2. Brown CC, Baker DC, and Baker, IK: Alimentary System. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 348-351. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

3. Caswell, CL and Williams KJ: Respiratory System. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 630,639 Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

4. Caudell D et al. Diagnosis of Infectious Canine HepatitisVirus (CAV-1) Infection in Puppies with Encephalopathy. J VET Diagn Invest. 2005,17:58-61

5. Decaro N et al. Canine Adenoviruses and Herpesviruses. Vet Clin Small Anim 2008;38:799-814

6. Fox JG et al. In: Laboratory Animal Medicine, 2nd ed, pp 185, Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 2002

7. Greene, CG. Infectious Canine Hepatitis and Canine Acidophil Cell Hepatitis. In: Greene Infectious Disease of the Dog and Cat. 3rd ed, pp 41-47. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2006

8. Kennedy FA et al: Disseminated adenovirus infection in a cat. J Vet Diagn Invest. 5, 1993: 273276

9. Kennedy, FA Feline Adenovirus Infection. IN: Greene Infectious Disease of the Dog and Cat. 3rd ed, pp143-144. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2006

10. Marschang RE, Viruses Infecting Reptiles. Viruses. 2011, 3(11): 2087-2126

11. McFerran JB, et al. Avian Adenoviruses. Rev sci tech Off int Epiz 2000;19 (2):589-601

12. Thompson D et al. Molecular confirmation of an adenovirus in brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula). Virus Res 2002 Feb 26;83(1-2):189-95

13. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA: Liver and biliary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 348-351. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

14. Summers BA, Cummings JF, deLahunta: Inflammatory Diseases of the Central Nervous System. IN: Veterinary Neuropathology, pp 117. Mosby-Year Book, Inc., St. Louis, MO, 1995

15. Zachary JF. Nervous system. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012:781-791.