Conference 15, Case 4

Signalment:

5-week-old, female, B6.129S4-C3tm1Crr/J mouse

History:

This female targeting a mutation in the complement component C3 (C3 KO) was 5 weeks old, and she had shown an abnormal enlarged abdomen (homogenous, firm but not very hard to touch). Apart from that she was in normal general condition, with no signs of dehydration nor malnutrition and no signs of diarrhea. Pregnancy is excluded since the animal has been kept in a stock cage with other females.

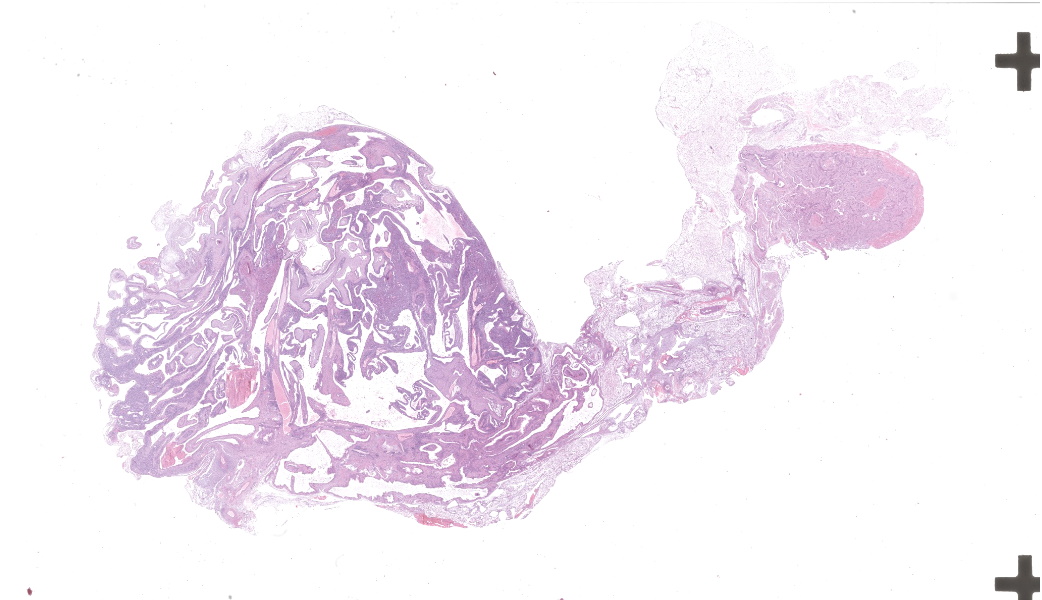

Gross Pathology:

A fresh carcass was received. No external lesions were observed apart from an enlarged abdomen, which was firm upon palpation.

Abdominal cavity: The abdominal cavity contained a moderate amount of clear, pale-yellow fluid.

Kidney: The left kidney was markedly enlarged, measuring approximately 8x5x4mm, along with an associated diffuse dilation of the left ureter (appr. 5mm in diameter). The left ureter and left kidney were transparent and filled with clear fluid (interpreted as urine). Renal parenchyma was not evident. A hole of approximately 5mm in length was observed in the left renal capsule. Size, surface and color of the right kidney appeared unremarkable, but on cut section, a moderately dilated renal pelvis was noted.

Other observed organs were macroscopically unremarkable.

Laboratory Results:

N/A.

Microscopic Description:

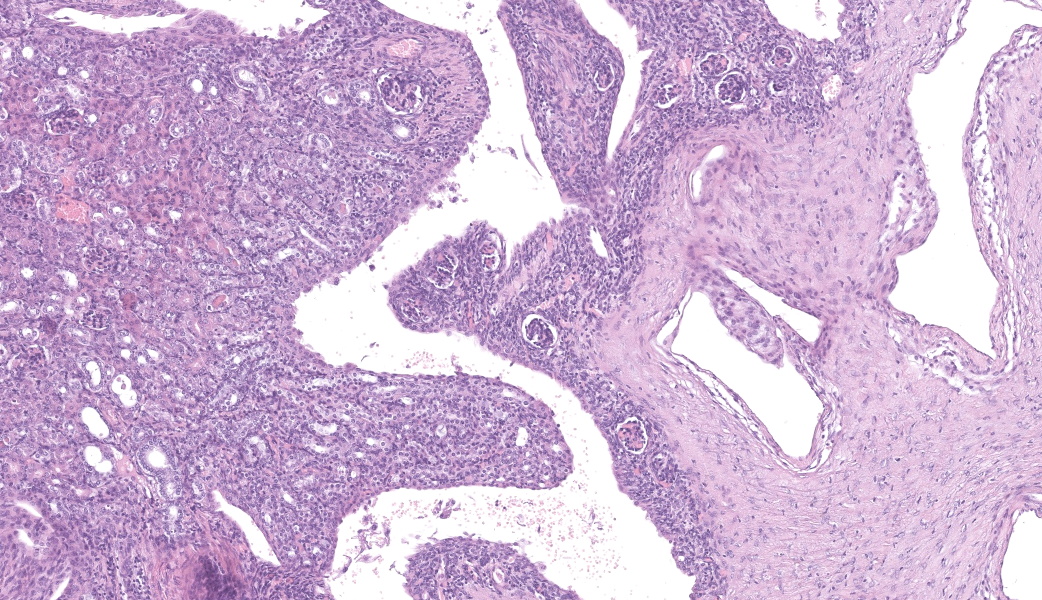

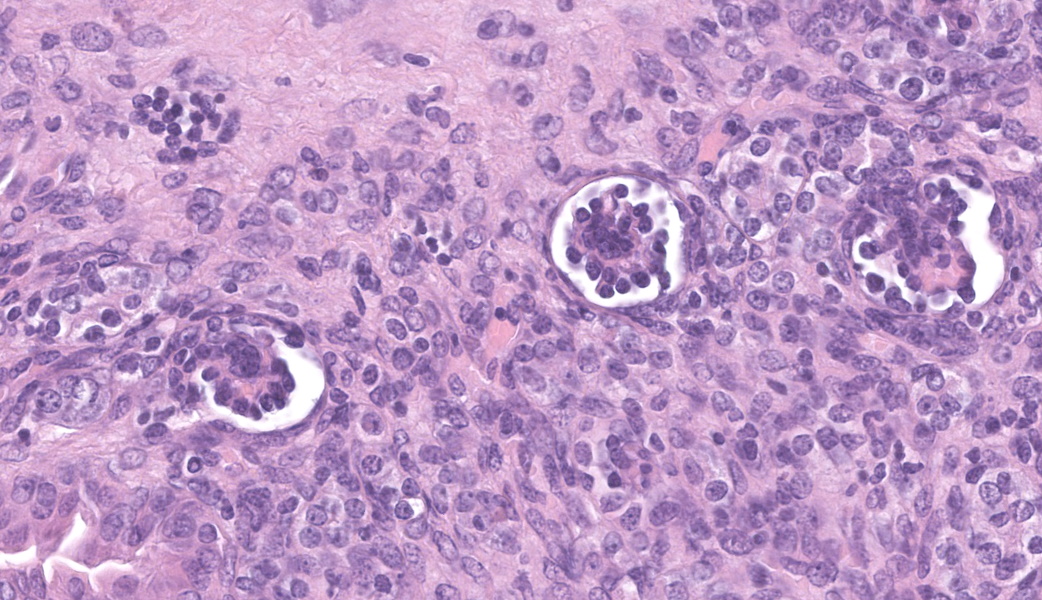

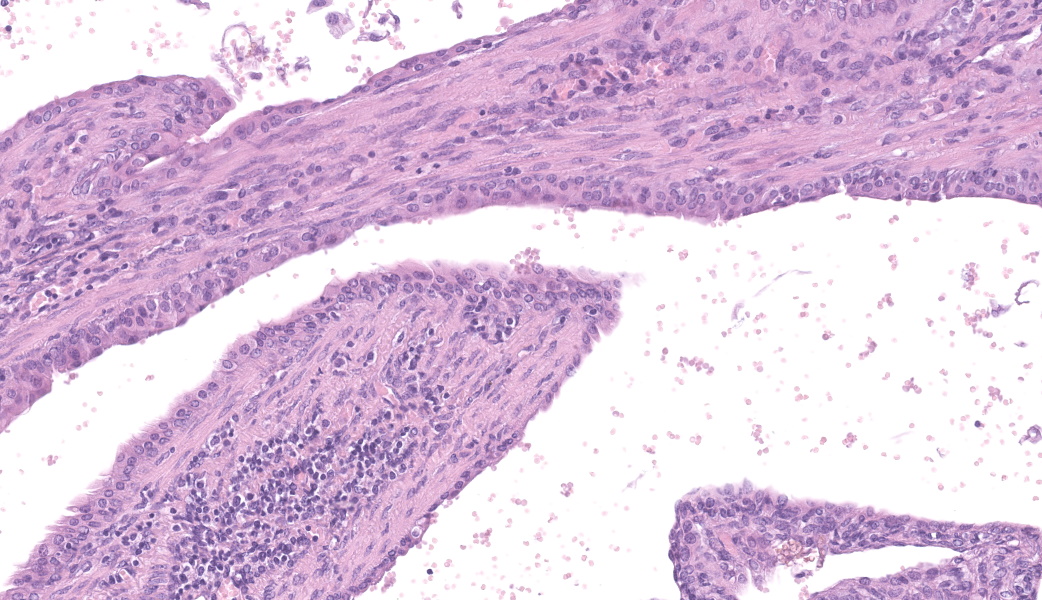

Left kidney: The left kidney is composed of multiple, largely dilated cavities that divide the kidney into numerous islands of parenchyma. These cavities are lined by 2–4 layers of cuboidal to highly columnar, eosinophilic epithelial cells with no mitotic activity (collecting ducts). Few sloughed epithelial cells and erythrocytes are present in the lumen of these ducts. The parenchyma contains islands of immature glomeruli with peripheral nuclei, poorly developed capillaries, and thickened Bowman’s capsule (vimentin positive). Primitive tubules are lined by large basophilic cuboidal epithelial cells with minimal or absent lumina. Other areas within the parenchyma consist of mature tubules and glomeruli with some tubules showing mild dilation and intraluminal protein casts. Collecting duct-like structures are multifocally surrounded by loosely arranged mesenchymal tissue (primitive mesenchyme). The interstitium is multifocally expanded by fibrous connective tissue and some areas are infiltrated by low to intermediate numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and occasional neutrophils. Some arteries are very prominent (large) with thickened media, and they appear tortuous. A medium sized artery is surrounded and infiltrated by inflammatory cells predominantely macrophages, neutrophils and occasionally multinucleated giant cells within adventitia, media and intima (transmural). Diffuse proliferation of fibroblasts and deposition of fibrin within the vessel wall is observed. Occasionally, the tunica intima is disrupted. Endothelial cell proliferation is evident with clustering of endothelial cells attempting to recanalize the affected lumina.

Left ureter: Multiple longitudinal and cross-sections of the ureter are present, consisting of urothelium, lamina propria, a smooth muscle layer, and an outer adventitial layer. The periureteral mesenchymal tissue similar to persistent mesenchyme was observed surrounding left ureter and multifocally contains fibrin and exhibits multifocal moderate hemorrhage, and is infiltrated by inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils and macrophages, with the presence of hemosiderophages.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Left kidney:

- Multicystic renal dysplasia with focal rupture of the capsule.

- Mild to moderate multifocal chronic lymphoplasmacytic tubulointerstitial nephritis.

- Severe diffuse chronic histiocytic arteritis

Contributor’s Comment:

Here, we present an interesting case of unilateral renal dysplasia with unusual cystic dilation of the pelvis and collecting ducts in laboratory mice. Renal dysplasia is well-documented in domestic animals due to its clinical significance; however, the condition has been rarely reported in rodents. Among rodents, renal dysplasia has been reported in a Wistar rat, a Sprague Dawley rat and a Syrian hamster.5,7,9 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported spontaneous occurring case of renal dysplasia in mice.

Renal dysplasia is a congenital or neonatal developmental anomaly of the kidney that results from disruption of the normal development of the collecting duct system.3 The disease is often congenital, caused by alterations in the renal branching morphogenesis, which occur due to changes in transcription factors, growth factors, and cell surface signaling peptides.3 It can also be caused by disease in the early neonatal period, before differentiation of the nephrogenic tissue is completed. This is true in species, which have an active subcapsular nephrogenic zone at birth such as cats, dogs, and pigs.3 In mice, nephrogenesis begins before day 11 of gestation and is completed at birth, whereas in dogs nephrogenesis is completed by post-natal day 14, and even later by post-natal day 21 in pigs and rabbits.4 This suggests that renal dysplasia in mice is more

likely to result from congenital anomalies rather than neonatal developmental abnormalities.

Grossly, dysplastic kidneys are usually misshapen, fibrosed with thick-walled cysts and dilated tortuous ureters.3 One or both kidneys can be affected and the condition can be clinically silent if unilateral, or embryonically lethal when bilateral.4 Key histological features of renal dysplasia include structures inappropriate to the stage of development or the presence of anomalous structures, in particular undifferentiated mesenchyme, metanephric blastema, immature glomeruli, blind ending collecting tubules, atypical tubular epithelium, metanephric ducts (lined by cuboidal or columnar epithelium), and metaplastic cartilage or bone (rare in domestic animals).3,8 These alterations could be masked by compensatory, degenerative or inflammatory changes.3

This is a case of unilateral renal dysplasia, including immature glomeruli, primitive tubuli and extensively dilated collecting duct-like structures surrounded by primitive mesenchyme. The presence of proteinaceous casts, extensive fibrosis and interstitial nephritis display secondary changes related to impaired renal function. Defective metanephric differentiation results from abnormal interaction between the uretic bud and metanephric blastema leading to renal dysplasia. Complete failure of initiating ureteric bud induction can be diagnosed histologically by the presence of metanephric ducts surrounded by primitive mesenchyme and dysontogenic tissue formation6. As observed in this case, the presence of fetal glomeruli, persistent mesenchyme, and anomalous tubular structures suggests that induction of metanephric blastema was initiated but failed to progress to full differentiation. This is further supported by the immunohistochemistry findings, which demonstrate the persistence of mesenchymal markers (vimentin) in primitive tubules alongside epithelial differentiation (cytokeratin positivity) in more developed structures.2

Renal dysplasia may be accompanied by extrarenal abnormalities including segmental ureteral agenesis of the associated dysplastic kidney and imperforate anus.3 Ureteral anomalies are frequently associated with renal dysplasia due to the close developmental relationship between the kidney and the collecting system. Reported ureteral abnormalities in cases of renal dysplasia include ectopic ureters, ureteral obstruction with hydronephrosis, hydroureter, and congenital urothelial cell hyperplasia.10,11 In this case, the ureter associated with the dysplastic kidney is largely dilated and supposably tortuous. While no significant histopathological abnormalities were observed in the ureter itself, its tortuous nature may have impaired urine drainage, potentially leading to progressive renal dilation and rupture.

The observed arteritis in the left kidney is notable. While arteritis is not a common feature of renal dysplasia, it can occur secondary to chronic inflammation or immune-mediated processes such as anti-Glomerular Basement Membrane (GBM) disease.6 In murine models, polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a recognized disease and is characterized by fibrinoid degeneration and necrosis of the tunica media and inflammation of medium and small arteries. This process is mostly associated with neutrophils with or without mononuclear leukocytes and thickening and fibrosis of the vessel wall.1 Changes often involve arteries of the tongue, head, pancreas, heart, kidneys, mesentery, urinary bladder, uterus, testes, and gastrointestinal tract. Lesions are segmental and their etiology is unknown, but immune complexes have been found in affected vessels.1 Polyarteritis is an incidental finding which can be associated with segmental infarction of the kidney and scarring.1

Although PAN has not yet been described as directly associated with renal dysplasia, chronic kidney injury may predispose to vascular inflammation. In addition, the knockout of C3 in this mouse is associated with defective antibody response to T cell dependent antigens, which might have contributed to disease development. However, arteritis was not observed in other examined organs. Additional investigations into the pathogenesis of arteritis in this case are therefore required.

This is the first case report of spontaneous renal dysplasia in mice. Possible causative relation of dysplastic changes and arteritis observed in this case remains unclear and requires further investigation to elucidate its etiology, particularly in the context of murine models of inflammation, such as C3 knockout.

Contributing Institution:

Institute of Animal Pathology

Vetsuisse Faculty – University of Bern

Länggassstrasse 122

CH-3012 Bern

Switzerland

www.itpa.vetsuisse.unibe.ch

JPC Diagnoses:

- Kidney: Congenital hydronephrosis, severe, with tubular and glomerular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, mild lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis.

- Kidney: Asynchronous maturation, with fetal glomeruli, rare primitive tubules, and primitive mesenchyme.

- Kidney, arteries and arterioles: Arteritis, neutrophilic and histiocytic, proliferative and necrotizing, chronic, multifocal, severe.

JPC Comment:

This case was fascinating and provided substantial discussion amongst participants, particularly on how best to morph these lesions. The contributor’s comment lays out many of the points of debate amongst participants and makes a strong argument for a congenital lesion with prominent secondary changes. The question most attendees were wondering was, “Which parts are congenital and which parts are secondary?”

The large number of fetal glomeruli, presence of few primitive tubules, and occasional primitive mesenchyme, especially in a 5-week old mouse, certainly suggest a degree of renal dysplasia. Mouse kidneys should be completely developed within 4 days of birth (no later than 7 days).1,5 However, there was debate amongst conference attendees on whether this was a primary renal dysplasia or a secondary delay in maturation due to atrophy caused by congenital hydronephrosis/hydroureter. The fetal glomeruli were strikingly obvious in this case and are characterized by a reduction in the number of capillaries, the presence of podocyte nuclei that palisade around the periphery of a small glomerular tuft, decreased tuft segmentation, and a thick Bowman’s capsule. Immature glomeruli are, in a not-so-convoluted kidney, usually best seen in the subcapsular cortex.1,5 Glomeruli aside, however, while there were rare definitively primitive tubules, most participants thought that many of the tubules were atrophied in response to the severe hydronephrosis rather than truly dysplastic. This was further complicated by the complete lack of medullary distal convoluted tubules. Additionally, there were occasional glomeruli that were mature and the majority of the scant interstitium was relatively developed. As such, many conference participants preferred the term “asynchronous maturation” to describe the spectrum of development seen within the kidney.

Participants wholeheartedly agreed with the contributor regarding the arteritis and similarly diagnosed polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) due to the degree of subintimal proliferation, neutrophilic inflammation, disruption of the elastic laminae, fibrinoid necrosis, and tortuosity of the arteries. Although usually associated with hypertension and most commonly seen in the pancreas, mesentery, and testes, renal PAN is well-documented.2,4 In this case, it is possible that the degree of hydronephrosis and subsequent pressure atrophy could have contributed to the development of hypertension-like lesions in the arteries, although this is purely speculative and could be a separate process entirely.

The flocculent, cystic spaces made definitive interpretation of this case challenging. The lining of the cystic spaces resembled either persistent metanephric ducts (ducts in the outer medulla lined by pseudostratified, ciliated, columnar epithelium), transitional urothelium, and/or serosa. Metanephric ducts in the medulla potentially represented persistent, incompletely differentiated ureteric bud branches that did not differentiate into normal collecting tubes as they are supposed to, further suggesting a congenital etiology in this condition.5,10 The presence of serosa-lined spaces implies that some cysts had collapsed in on themselves during processing. Everyone unanimously agreed, however, that this was not polycystic kidney disease.

Differentiating between cystic renal dysplasia and polycystic kidney disease can be challenging, but there are some key differences to be aware of. Cystic renal dysplasia (CRD) is the most common pediatric renal disease in humans (and is also more common in most animals). It typically has larger cysts that are variably sized and lined by flat-cuboidal epithelium. CRD usually results from urinary tract obstruction and is often unilateral. It occurs sporadically and does not have a defined inheritance pattern like PKD. The characteristic findings for renal dysplasia will be present (fetal glomeruli, primitive tubules, primitive loose mesenchyme, +/- cartilaginous metaplasia, +/- mesenchymal collarettes), and there may or may not be vascular changes.4,10

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD), on the other hand, is divided into two subtypes: autosomal dominant PKD (ADPKD) and autosomal recessive PKD (ARPKD). ADPKD is familial, bilateral, and usually does not present until adulthood.4,10 There is no immature mesenchyme or cartilage present. ARPKD is also familial and bilateral but is generally present at birth.4 The cysts in ARPKD arise from the collecting ducts and are typically uniform, radially arranged, and fusiform. There is similarly no immature mesenchyme or cartilage.

Due to the differing stages of maturation and the convolution of this case, the JPC consulted with Texas A&M’s Dr. Rachel Cianciolo, one of the premier renal experts in veterinary pathology. Her conlusions matched those of some of our more experienced conference particpants in that, while there are abundant fetal glomeruli, there are some that are more mature, but smaller and atrophic. According to Dr. Cianiolo, this supports a diagnosis of a congenital hydronephrosis with delayed renal development, making this case an example of a congenital anomaly of the kidney and urinary tract. She also believes, as did many of our conference attendees, that the cysts are mostly irregular cuts of a severely dilated renal pelvis and calyceal diverticula rather than tubular cysts. Lastly, she stated that, in order to determine if this condition was truly destructive to the kidney and surrounding structures, imaging studies would be necessary. While cost certainly can dictate whether or not imaging will be done in a case, it should be considered in anomalalies like this where imaging could provide additional supportive evidence for a diagnosis, as well as scratch the academic itch to “know”! Many thanks Dr. Cianciolo for sharing her expertise on this interesting case!

References:

- Baldock RA, Armit C. eHistology image and annotation data from the Kaufman Atlas of Mouse Development. Gigascience. 2018;7(2):gix131.

- Barthold SW, Griffy SM, Percy DH. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, Fourth Edition. 4th ed. (Barthold SW, Griffey SM, Percy DH, eds.). Wiley; 2016.

- Carev D, Saraga M, Saraga-Babic M. Expression of intermediate filaments, EGF and TGF-alpha in early human kidney development. J Mol Histol. 2008;39(2):227-235.

- Cianciolo R., Mohr F. Urinary system. In: Maxie M., ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016:376-464.

- Elmore SA, Kavari SL, Hoenerhoff MJ, et al. Histology atlas of the developing mouse urinary system with emphasis on prenatal days E10.5-E18.5. Toxicol Pathol. 2019;47(7):865-886.

- Frazier KS. Species Differences in Renal Development and Associated Developmental Nephrotoxicity. Birth Defects Res. 2017;109(16):1243-1256.

- Ikeyama Seiichi, Nishibe Tadayuki, Furukawa Satoshi, Goryo Masanobu, Okada Kosuke. Unilateral Renal Dysplasia in a Syrian Hamster. J Toxicol Pathol. 2001;14(4):309-312.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1-11.

- Lee Y-H, Kim D, Park SH, et al. Unilateral non-cystic renal dysplasia in a Sprague Dawley rat. J Biomed Res. 2014;15(2):92-95.

- Picut CA, Lewis RM. Microscopic features of canine renal dysplasia. Vet Pathol. 1987;24(2):156-163.

- Schorsch F, Pohlmeyer-Esch G, Lasserre- Bigot D. Unilateral Renal Agenesis/ Dysplasia associated with Contralateral End-Stage Kidney Disease in Two Wistar Rats. Eur J Vet Pathol. 2001;7(3):127-134.

- The Joint Pathology Center (JPC). JPC Wednesday Slide Conference 2023-2024, Conference 5, Case 04. Published 2023.

- Yoshida K, Takezawa S, Itoh M, et al. Renal Dysplasia with Hydronephrosis and Congenital Ureteral Stricture in Two Holstein-Friesian Calves. J Comp Pathol. 2022;193:20-24.