Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

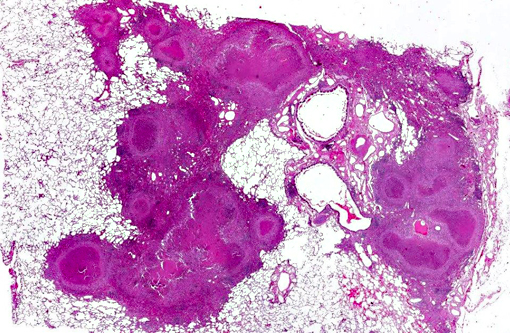

The primary lesion of simian tuberculosis is the typical tubercle. Lesions can vary from non-detectable lesions to widely disseminated characteristic granulomas. The granulomas are firm yellow-white or greyish nodules of different size. Palpable firm nodules may affect all major organs, but the lung is the most commonly affected organ system. Gross lesions also include large cavernous and coalescing lesions within the lung and tubercles may extend into the thoracic pleura or trachea. Alterations can be accompanied by enlarged tracheobronchial lymph nodes with focal or multifocal granulomas and loss of nodal architecture to various degrees. Advanced stages of the disease are characterized by secondary spread to spleen, kidney, liver and different lymph nodes.(4) Dissemination to spleen, liver, and other organs varies among monkeys and does not necessarily correlate with the severity of lung involvement.

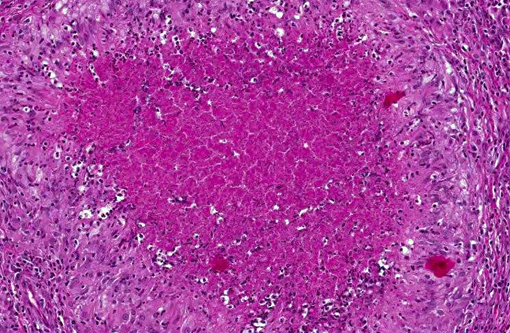

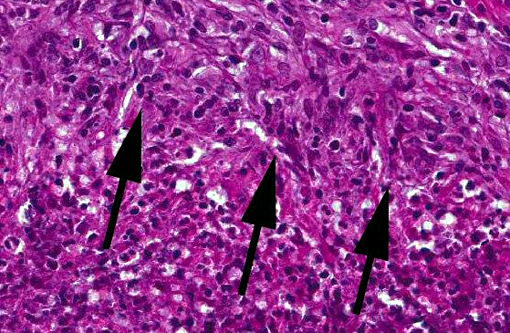

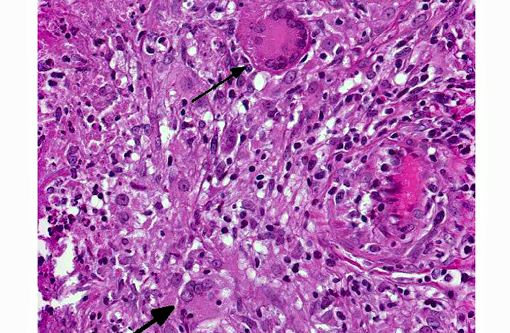

Microscopic findings are dependent on duration and extension of the disease. The histopathological hallmark is the granuloma. In experimental studies, a wide spectrum of different granuloma types can be seen depending on the stage of disease.(6) Early stages of the disease are characterized by small granulomas consisting of circumscribed accumulations of epithelioid cells and few Langhans-type giant cells confined to the lung or the intestinal tract. Advanced stages of the disease are characterized by the classic tubercle formation. Tubercles are typical caseous granulomas of varying size containing a caseous center consisting of acellular necrotic debris or proteinaceous material. The central cores are surrounded by a mantle zone of epithelioid cells and a band of plasmacytic and lymphocytic cells interspersed with only a few Langhans-type giant cells. In contrast to other animal species, a fibrous capsule is usually not found in nonhuman primates. Non-necrotizing granulomas are merely composed of epithelioid macrophages and Langhans-giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes. These solid granulomas exclusively occur in active TB. Fibrocalcific granulomas are composed of various combinations of fibrous connective tissue and mineral deposition. These lesions are generally observed in monkeys with latent infection. However, calcification is usually rare or lacking. Experimental studies show that only long-term non-progressive lesions tend to calcify.(3) The number of acid-fast bacilli within granulomatous lesions can vary considerably. Hence, it can be difficult to demonstrate the bacteria within histologic slides, like in the present cases. Therefore, the microscopic examination alone is not sufficient for the diagnosis of simian tuberculosis. A combination of different test methods based on serology, x-ray, histology and microbiology is advisable to accurately diagnose simian TB.(2)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Along with the contributor, we also performed acid-fast stains on these sections and did not identify a single organism. This is often typical of tuberculoid granulomas, which are TH1-driven lymphocytic responses to infection of Mycobacterium spp. The macrophages in these lesions are actually utilized by the bacteria to facilitate its spread, as their cellular uptake is promoted by the recognition of multiple membrane pathogen receptors including complement, mannose, surfactant protein, and CD14. Within the macrophage, they disrupt phagosome-lysosome fusion and are able to grow, replicate, and subsequently disseminate.(8)

Following this period of bacterial proliferation, typically about 3 weeks after infection in humans, TH1 lymphocytes are produced following stimulation of TLR2 by mycobacterial ligands which ramp up production of IL-12. TH1 cells produce IFN-γ in abundance, which are the critical mediators enabling macrophages to contain the infection. Additionally, IFN-γ orchestrates the formation of granulomas by inducing differentiation of macrophages into their epithelioid versions which aggregate and often fuse to form giant cells. The immune response, while effective as evidenced by the lack of bacteria present in the current case, comes at the cost of tissue destruction.(7)

Interestingly, a von Kossa stain demonstrated no mineral within the granulomas in this case. Central mineralization occurs commonly in stage III of granuloma formation (which occurs several weeks to a month following infection) and is characterized by a mineralized necrotic center with more organized zones of lymphocytes, fibroblasts and a fibrous connective tissue capsule.(1) Mineralization is not usually present in active infections. The lesions in this case also lack prominent fibrous capsules and the abundant neutrophils present with lack of mineralization suggest an earlier form of disease such as stage I or II. As the contributor mentioned, this presentation may be more common in primates, as mineralization is less often described in contrast to its common occurrence in cattle.(1)

References:

1. Ackermann MR. Inflammation and healing. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012:122-124.

2. Bushmitz M, Lecu A, Verreck F, Preussing E, Rensing S, M+â-ñtz-Rensing K. Guidelines for the prevention and control of tuberculosis in non-human primates: recommendations of the European Primate Veterinary Association Working Group on Tuberculosis. J Med Primatol. 2009;38(1):59-69.

3. Capuano SV 3rd, Croix DA, Pawar S, et al. Experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of cynomolgus macaques closely resembles the various manifestations of human M. tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2003;71(10):58315844.

4. Garcia MA, Bouley DM, Larson MJ, et al. Outbreak of Mycobacterium bovis in a conditioned colony of rhesus (Macaca mulatta) and cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) macaques. Comp Med. 2004a; 54(5):578-584.

5. Garcia MA, Yee J, Bouley DM, Moorhead R, Lerche NW. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in macaques using whole-blood in vitro interferon-gamma (PRIMAGAM) testing. Comp Med. 2004b;54(1):86-92.

6. Lin PL, Rodgers M, Smith L, et al. Quantitative comparison of active and latent tuberculosis in the cynomolgus macaque model. Infect Immun. 2009;77(10):4631-42.

7. McAdam AJ, Milner DA, Sharpe AH. Infectious diseases. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:371-378.

8. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012:181-182.