CASE 1: WSC Case 2 (4153750-00)

Signalment:

2-year-old, female spayed, ferret, Mustela putorius furo

History:

The ferret presented four months of history of hindlimb weakness with evidence of diarrhea. Blood examination revealed slight anemia and hyperglobulinemia and elevated creatinine. Urine protein electrophoresis was unremarkable, and the blood protein electrophoresis showed a polyclonal spike. CT scan of the spinal cord showed no abnormalities. The animal became acutely paraplegic one night, and euthanasia and post-mortem examination were elected.

Gross Pathology:

The right adrenal gland was moderately enlarged and had multiple variably sized, discrete, white to tan nodules, near the termination of the right limb of the pancreas with adhesions to the mesentery and duodenum, and a single nodule within the right renal cortex. Significant abdominal lymphadenomegaly and splenomegaly were present.

Laboratory results:

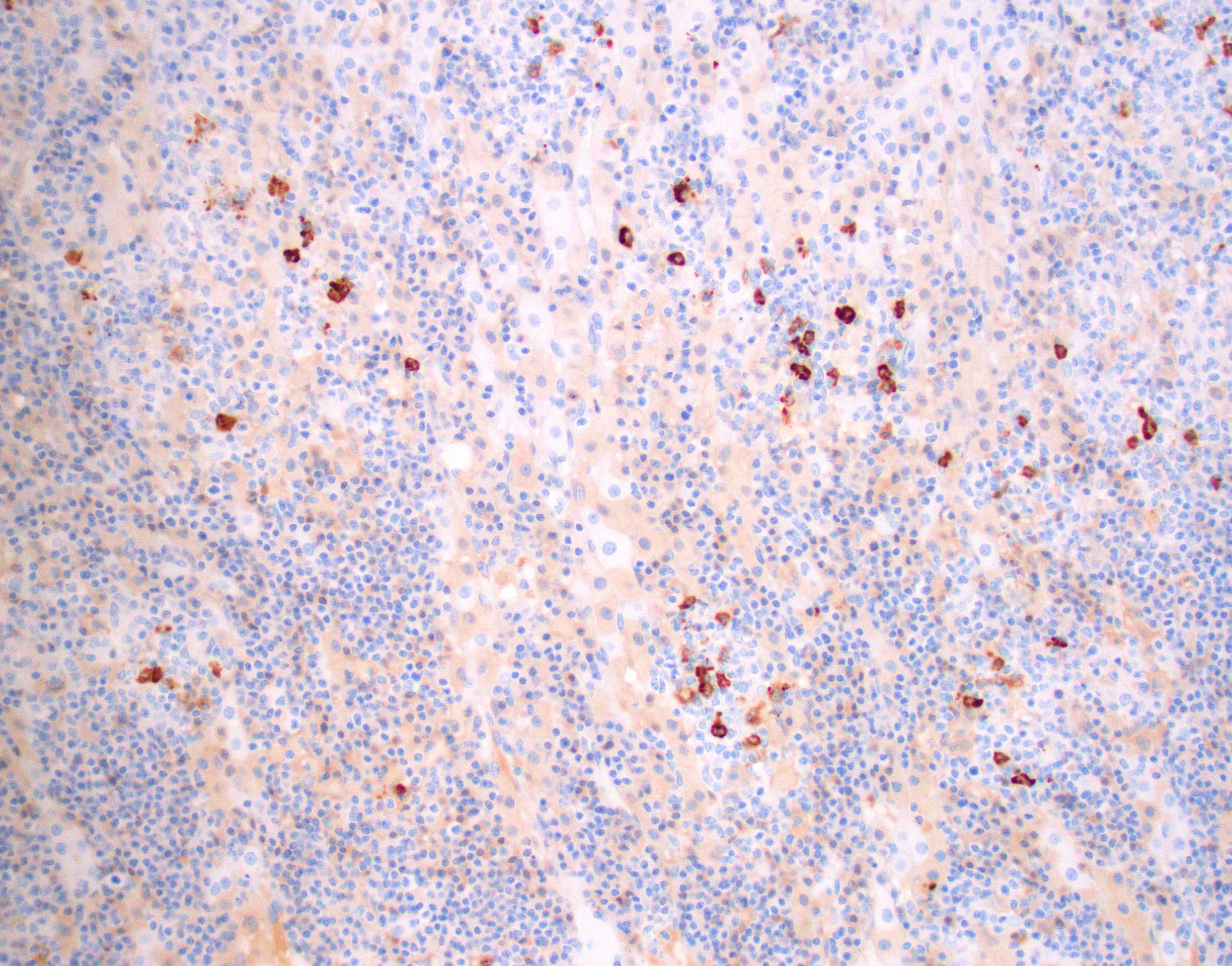

Lesions in the brain and adrenal glands reacted strongly positive for coronavirus gp70 antigen

Fecal PCR for Aleutian Disease Virus and Ferret Coronavirus Genotype 1 and Genotype 2: All were negative

Hematology:

|

|

Result |

Reference |

Units |

|

WBC |

4.40 |

4.3-10.7 |

x103/ul |

|

RBC |

7.23 |

7.01-9.65 |

x106/ul |

|

Hemoglobin |

11.7 |

12.2-16.5 |

gm/dl |

|

Hematocrit |

33.0 |

36-48 |

% |

|

MCV |

45.7 |

50-54 |

fl |

|

MCH |

16.2 |

15-18 |

pg |

|

MCHC |

35.4 |

32-35 |

gm/dl |

|

RDW |

12.8 |

|

% |

|

Platelet-Auto |

220 |

200-459 |

x103/ul |

|

MPV |

7.2 |

|

fl |

Chemistry:

|

|

Result |

Reference |

Units |

|

BUN |

25 |

12-43 |

mg/dl |

|

Creat |

0.9 |

0.2-0.6 |

mg/dl |

|

Glucose |

205 |

62.5-134 |

mg/dl |

|

Total Protein |

9.1 |

5.3-7.2 |

gm/dl |

|

Albumin |

2.9 |

2.5-4.0 |

gm/dl |

|

Alk Phos |

45 |

25-60 |

IU/L |

|

ALT |

42 |

14-80 |

IU/L |

|

Hemolytic Indice |

15.0 |

|

|

|

Icteric Indice |

2.0 |

|

|

|

Lipemic Indice |

20.0 |

|

|

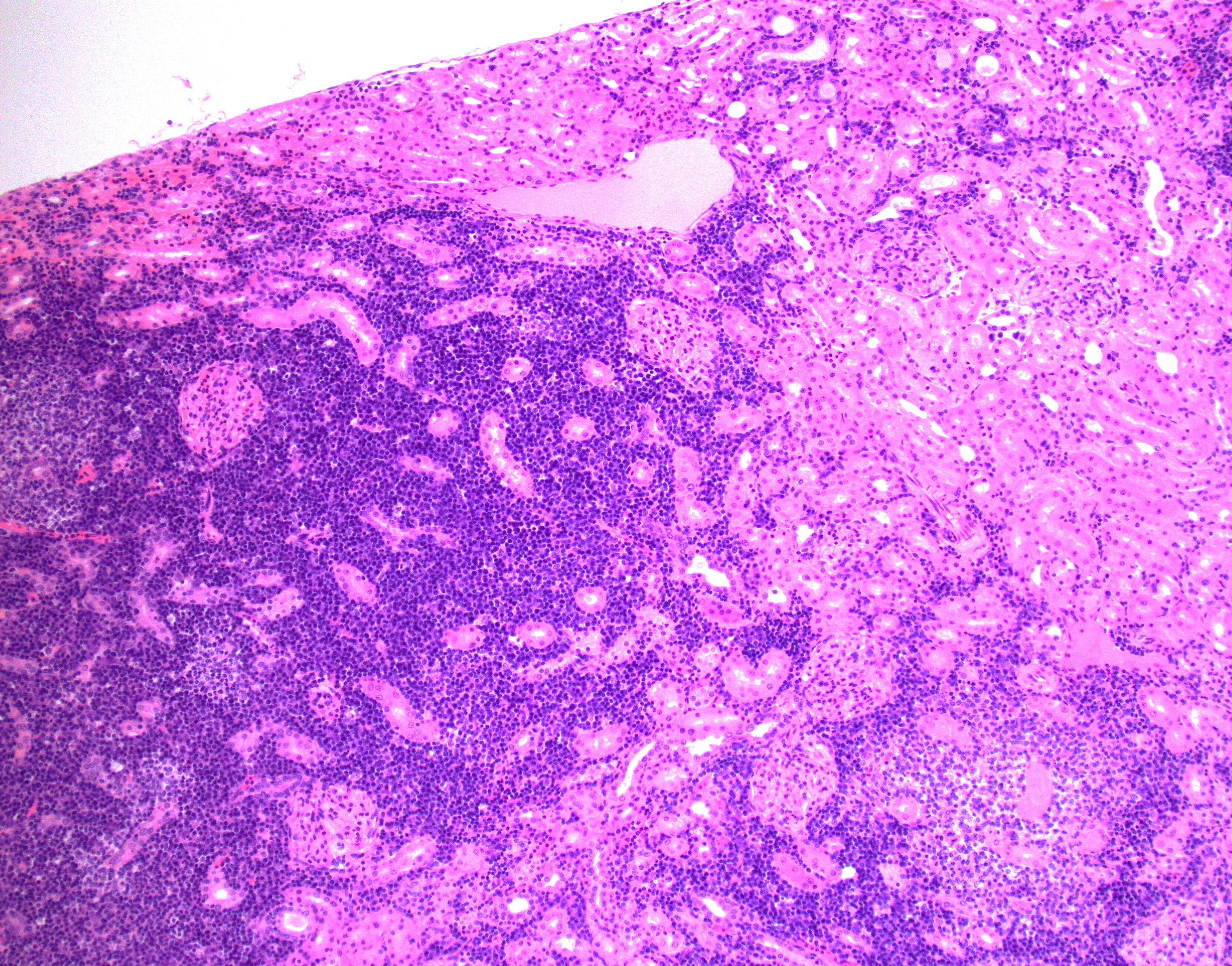

Microscopic description:

Cerebrum, diencephalon, cerebellum, and brainstem: A parasagittal section of the brain is examined. Multifocally and extensively expanding the leptomeninges, Virchow-Robin space, 3rd and 4th ventricle subependyma, choroid plexus, and infiltrating the perivascular and periventricular neuroparenchyma are infiltrates of moderate numbers of lymphocytes, epithelioid macrophages, some plasma cells, and few viable and degenerate neutrophils. The infiltrates usually surround and obscure vessel walls (predominantly veins/phlebitis). Periventricular and meningeal blood vessel walls are often lined by prominent plump, hypertrophic endothelial cells (reactive) and there are circumferential infiltrates of 5-6 layers of lymphocytes and plasma cells expanding Virchow Robbins space. Multifocally, the tunic media and adventitia are expanded and obscured by accumulation of eosinophilic fibrillar material (fibrin). The inflammatory infiltrates multifocally extend beyond Virchow-Robin space into the brainstem and periventricular neuroparenchyma resulting in rarefication and malacia of the neuropil. The adjacent neuropil is expanded by mild to moderate gliosis composed of gemistocytic astrocytes, gitter cells, and microglia.

Adrenal gland: The adrenal architecture of the cortex and medulla is almost completely effaced and severely infiltrated by marked infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells surrounding small aggregates of epithelioid macrophages and occasionally oriented around a central hypereosinophilic and karyorrhectic cellular debris (granuloma). There are similar granulomas with inflammatory infiltrates that extends into the capsule, tunica adventitia and tunica media of the overlying vena cava lined by undulating plump endothelial cells.

(Note: There are slide variation in the submission. A few slides contain section of the adrenal gland)

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Cerebrum, cerebellum and brainstem: Meningoencephalitis, perivascular and periventricular, multifocal, pyogranulomatous and lymphoplasmacytic, with phlebitis, periventriculitis, and chorioependymitis, chronic, marked

Adrenal gland: Adrenalitis, multifocal to coalescing, pyogranulomatous and lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, marked

Contributor's comment:

This was a case with morphological findings that were compatible with the infection of ferret systemic coronavirus (FRSCV) and was confirmed by immunohistochemical staining with feline coronavirus anti-gp70 antibody that often cross-reacts with ferret coronavirus. FRSCV-associated disease has been reported in Europe and the USA in the last two decades as a novel and fatal ferret disease remarkably similar to the dry form of feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) in cats.4,9,10,14 This disease was found associated with an alphacoronavirus that is closely related to ferret enteric coronavirus (FRECV), the cause of epizootic catarrhal enteritis.10,18 However, sequence data from a limited number of enteric and systemic strains showed that FRSCV differs more from FRECV than feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) does from FCoV.19 The speculation that FRSCV has similar pathogenesis as FIP has not been confirmed experimentally.12,19,20 Based on the lower similarity of their S proteins amino acid sequence (79.6%), two ferret coronavirus genotype-specific real-time RT-PCR assays have been developed and remains the gold standard for differentiating between the two viruses.12,19 Immunohistochemistry using a monoclonal antibody against alphacoronavirus antigen can detect either FRECV or FRSCV but cannot distinguish them.5,18

The clinical and pathologic findings in ferrets with FRSCV resemble the non-effusive form of FIPV-induced diseases. FRSCV typically affects ferrets younger than 18 months of age and has common clinical signs of diarrhea, weight loss, lethargy, hyporexia/anorexia, and vomiting.4,12,14 Ferrets sometimes present primarily neurological symptoms, including hind limb paresis or paraparesis, ataxia, tremors, head tilt, and seizures.4,12 These clinical signs and hematology findings of nonregenerative anemia, hyperglobulinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and thrombocytopenia are strongly suggestive of the disease but not definite. Serum protein electrophoretograms of FRSCV usually present a polyclonal gammopathy.4,11-12,14 The histologic evaluation of biopsied or necropsied tissues with demonstrations of intralesional coronaviral nucleic acid remains the definite diagnosis.1,11

Predominant gross findings in ferrets with FRSCV include mesenteric lymphadenomegaly and multifocal to coalescing, white to tan irregular nodules of various sizes dispersed along serosal surfaces and mesenteric vessels.4,12 The inflammation commonly encompasses the small intestines with focal expansion or may completely destroy the muscularis and serosa. Nodules can be found in numerous other organs with the liver, kidneys, spleen, and lung being the commonly affected sites.4,14 These granulomas are histologically similar to those described in FIP,2,4 comprising pyogranulomatous to granulomatous inflammation with a central area of necrosis and degenerative neutrophils surrounded by epithelioid macrophages with occasional multinucleated giant cells, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, and a variable degree of fibrosis.1,4,12 Granulomatous inflammation is often centered on vessels and frequently involved the adventitia; thus vasculitis of small arterioles and venules are also common findings.1,4,12 In ferrets with neurological signs, lesions may be found primarily within the brain with severe pyogranulomatous leptomeningitis, choroiditis, ependymitis, and encephalomyelitis. The inflammation is mainly perivascularly with extension into the underlying parenchyma.12

Gross findings in this case with enlarged adrenal gland, multiple nodules, abdominal lymphadenomegaly, and splenomegaly initially led to the diagnosis of neoplastic diseases. Common primary neoplasms in ferrets include pancreatic islet cell tumors, adrenocortical tumors, and lymphomas.3 The development of multiple neoplasms, especially islet tumors and adrenal tumors, is not uncommon.3 Other differential diagnoses of nodules in ferrets include other granulomatous diseases such as mycobacteriosis and infection with Pseudomonas luteola.8,15 It is thus noteworthy that when seeing nodular lesions in ferrets, FRSCV should be considered a potential diagnosis.

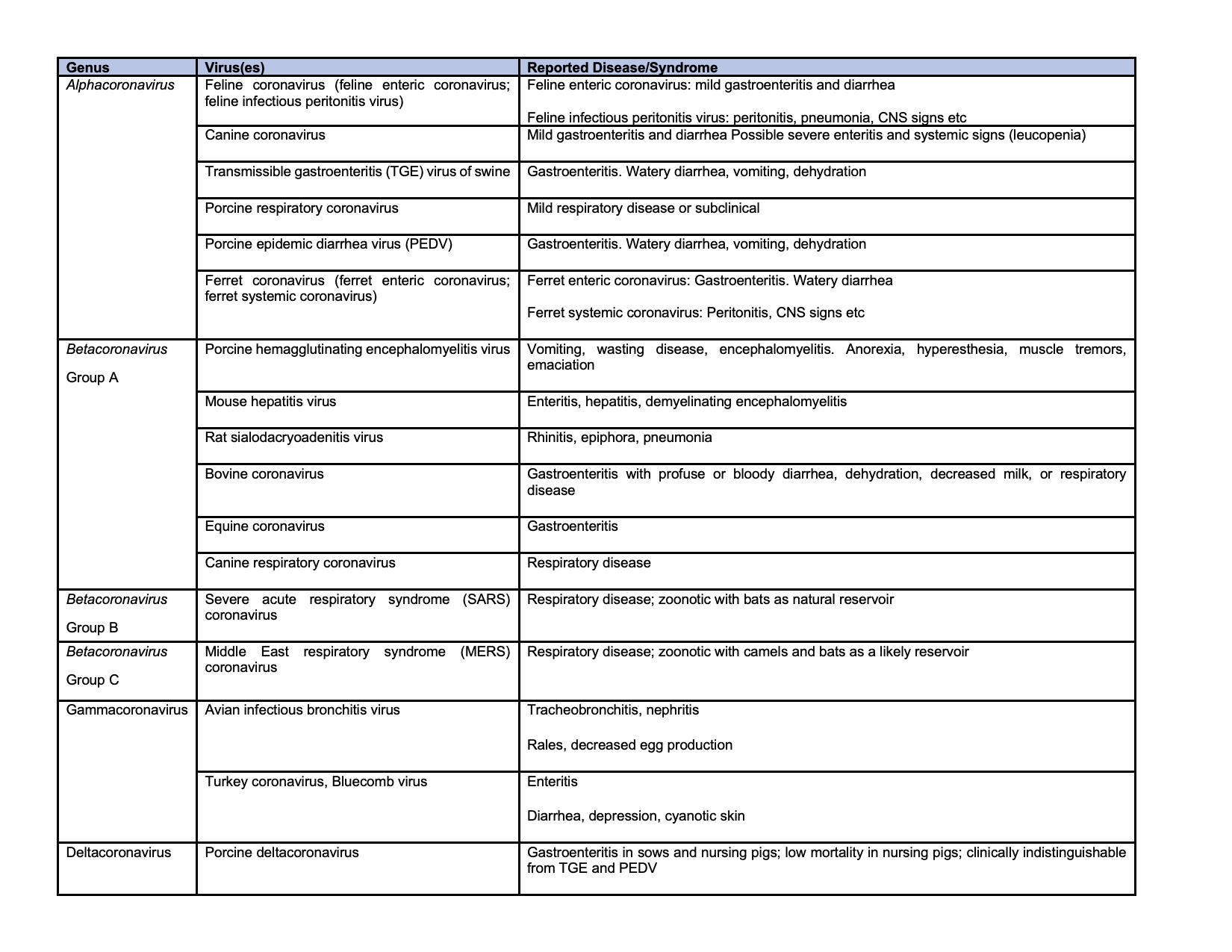

Coronaviruses are large, enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses constitute the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae of the Coronaviridae family, in the order Nirdovirales (http://www.ictvonline.org).7 The subfamily can be classified into four genera: Alphacoronavirus (alphaCoV), Betacoronavirus (betaCoV), Deltacoronavirus (deltaCoV), and Gammacoronavirus (gammaCoV).7 The former two genera are known to infect mammals, while deltaCoV and gammaCoV mainly infect wild birds.7 Numerous important enteric diseases in animals are caused by alphacoronavirus, formerly classified as group 1 coronaviruses, including porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus, canine coronavirus, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, feline coronavirus (FCoV), and ferret enteric coronavirus (FRECV).7,20 The recent outbreaks of viral pneumonia in human, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) were all caused by betaCoV.6,7,21 Coronaviruses of veterinary importance are summarized in the chart.4,7

Contributing Institution:

Iowa State University

College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Ames, IA 50010-1250

https://vetmed.iastate.edu/vpath

JPC diagnosis:

Brain: Phlebitis, histiocytic and lymphocytic, multifocal, severe, with histiocytic and lymphocytic meningoencephalitis, choroiditis, and ventriculitis.

JPC comment:

The contributor provides an excellent review of ferret systemic coronavirus, as well as a concise summary of coronaviruses of veterinary importance. As previously mentioned, the clinical signs of ferret systemic coronavirus infection are non-specific, and often include lethargy, diarrhea, vomiting, hyporexia or anorexia, and weight loss. These patients may have non-regenerative anemia, neutrophilia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphopenia. In addition to these signs, a recent case report may expand the list of pathologic changes due to infection. A 1 year old spayed female ferret initially presented for lethargy, inappetence, sneezing, and vomiting, but ultimately progressed to a state with non-regenerative anemia, severe pancytopenia, and hyperglobulinemia. This case detected the virus in bone marrow, which had abundant hemorrhage and necrosis throughout the medullary cavity, novel findings to date for FRSCV.17

With recent world events bringing attention to mink farms and the spread of SARS-CoV-2 within farmed populations, attention turned to the ferret as a potential animal model of the COVID-19. The ferret remains susceptible to SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, but is not susceptible to MERS-CoV through experimental infection. Ferrets are also capable of efficient transmission of the SARS viruses to naïve animals, making them candidates for pathogenicity and transmission studies.16

Recent therapeutic interventions for feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) have included protease inhibitors, which have met with moderate success. Coronaviruses encode two viral proteases, 3C-like protease and papain-like protease. Previous research has shown antiviral therapeutics targeting 3C-like protease has had efficacy against SARS coronavirus, MERS coronavirus, and murine and feline coronaviruses, and now ferret and mink coronaviruses as well. Challenges remain in the development of these antiviral therapeutics, but this may represent a future option for ferrets and minks in the future.13

References:

1. Autieri CR, Miller CL, Scott KE, et al. Systemic coronaviral disease in 5 ferrets. Comp Med. 2015; 65: 508-516.

2. Doria-Torra G, Vidana B, Ramis A, Amarilla SP, Martinez J. Coronavirus infection in ferrets: Antigen distribution and inflammatory response. Vet Pathol. 2016; 53: 1180-1186.

3. Fox JG, Muthupalani S, Kiupel M, Williams B. Neoplastic diseases. In: Fox JG, Marini RP ed. Biology and Diseases of the Ferret. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Wiley; 2014: 587-626.

4. Garner MM, Ramsell K, Morera N, et al. Clinicopathologic features of a systemic coronavirus-associated disease resembling feline infectious peritonitis in the domestic ferret (Mustela putorius). Vet Pathol. 2008; 45: 236-246.

5. Kiupel M, Perpiñán D. Viral diseases of ferrets. In: Fox JG, Marini RP ed. Biology and Diseases of the Ferret. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Wiley; 2014: 439-517.

6. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early Transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382: 1199-1207.

7. MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ. Chapter 24 - Coronaviridae. In: MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ ed. Fenner's Veterinary Virology 5th ed. Boston, MA: Academic Press, 2017: 435-461.

8. Martinez J, Martorell J, Abarca ML, et al. Pyogranulomatous pleuropneumonia and mediastinitis in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) associated with Pseudomonas luteola Infection. J Comp Pathol. 2012; 146: 4-10.

9. Martinez J, Ramis AJ, Reinacher M, Perpinan D. Detection of feline infectious peritonitis virus-like antigen in ferrets. Vet Rec. 2006; 158: 523.

10. Martinez J, Reinacher M, Perpinan D, Ramis A. Identification of group 1 coronavirus antigen in multisystemic granulomatous lesions in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). J Comp Pathol. 2008; 138: 54-58.

11. Mayer J, Marini RP, Fox JG. Chapter 14 - Biology and diseases of ferrets. In: Fox JG, Anderson LC, Otto GM, Pritchett-Corning KR, Whary MT ed. Laboratory Animal Medicine 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Academic Press; 2015: 577-622.

12. Murray J, Kiupel M, Maes RK. Ferret coronavirus-associated diseases. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2010; 13: 543-560.

13. Perera KD, Kankanamalage ACG, Rathnayake AD, et al. Protease inhibitors broadly effective against feline, ferret and mink coronaviruses. Antiviral Research. 2018;160:79-86.

14. Perpinan D, Lopez C. Clinical aspects of systemic granulomatous inflammatory syndrome in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). Vet Rec. 2008; 162: 180-184.

15. Pollock C. Mycobacterial infection in the ferret. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2012; 15: 121-129, vii.

16. Stout AE, Guo Q, Millet JK, de Matos R, Whittaker GR. Coronaviruses associated with the Superfamily Musteloidea. mBio. 2021;12(1):e02873-20.

17. Tarbert DK, Bolin LL, Stout AE, et al. Persistent infection and pancytopenia associated with ferret systemic coronaviral disease in a domestic ferret. J Vet Diag Invest. 2020;32(4):616-620.

18. Williams BH, Kiupel M, West KH, Raymond JT, Grant CK, Glickman LT. Coronavirus-associated epizootic catarrhal enteritis in ferrets. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000; 217: 526-530.

19. Wise AG, Kiupel M, Garner MM, Clark AK, Maes RK. Comparative sequence analysis of the distal one-third of the genomes of a systemic and an enteric ferret coronavirus. Virus Res. 2010; 149: 42-50.

20. Wise AG, Kiupel M, Maes RK. Molecular characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE) in ferrets. Virology. 2006; 349: 164-174.

21. Xu X, Chen P, Wang J, et al. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci China Life Sci. 2020; 63: 457-460.