Conference 15, Case 1:

Signalment:

29 week old, intact female, C57BL/6NCrl mouse (Mus musculus)

History:

This animal was utilized in a study of chronic kidney disease and was euthanized at a pre-defined study endpoint.

Gross Pathology:

The body weight was 14 g and the mouse had decreased fat stores. Bilaterally the kidneys were diffusely pale-tan and shrunken with a pitted appearance and miliary white depressed foci.

Laboratory Results:

Serum chemistry demonstrated elevated BUN (94 mg/dL; ref 5-28), creatinine (0.54 mg/dL; ref 0.20-0.50), globulin (2.9 g/dL; ref 1.7-2.2), and phosphorous (15.4 mg/dL; ref 7.3-14.5).

Complete blood count demonstrated a microcytic, hypochromic, regenerative anemia (HCT 33.2%, ref 37.2-62.0; MCV 36.1 fL, ref 42.6-56.0; MCH 11.3 pg, ref 13-16.8; RET 603.8 K/uL, ref 294-444).

Automated leukocyte differential demonstrated leukopenia (3.26 K/uL, ref 3.9-13.96) characterized by a lymphopenia (0.82 K/uL, ref 2.88-10.92).

Urine specific gravity was low (1.015, ref 1.050-1.093).

Microscopic Description:

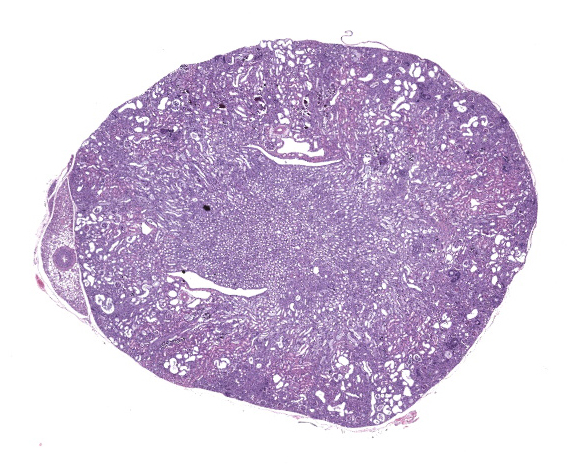

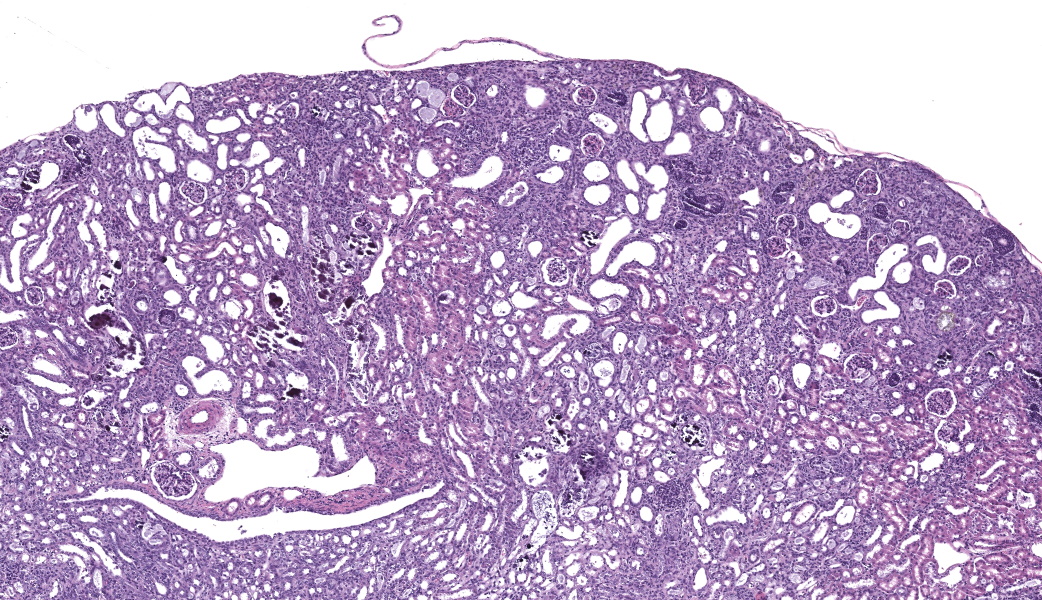

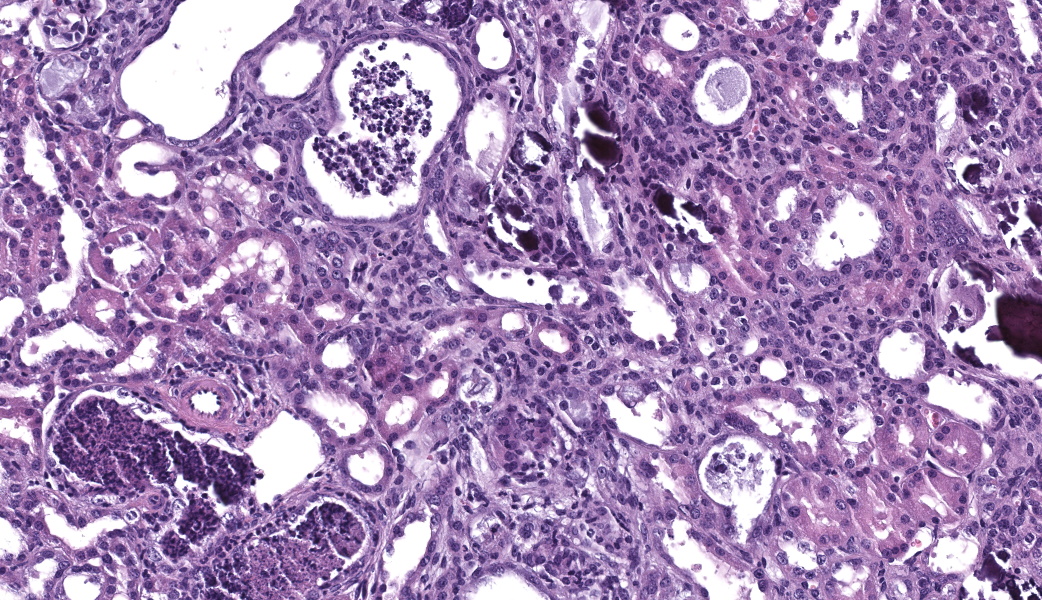

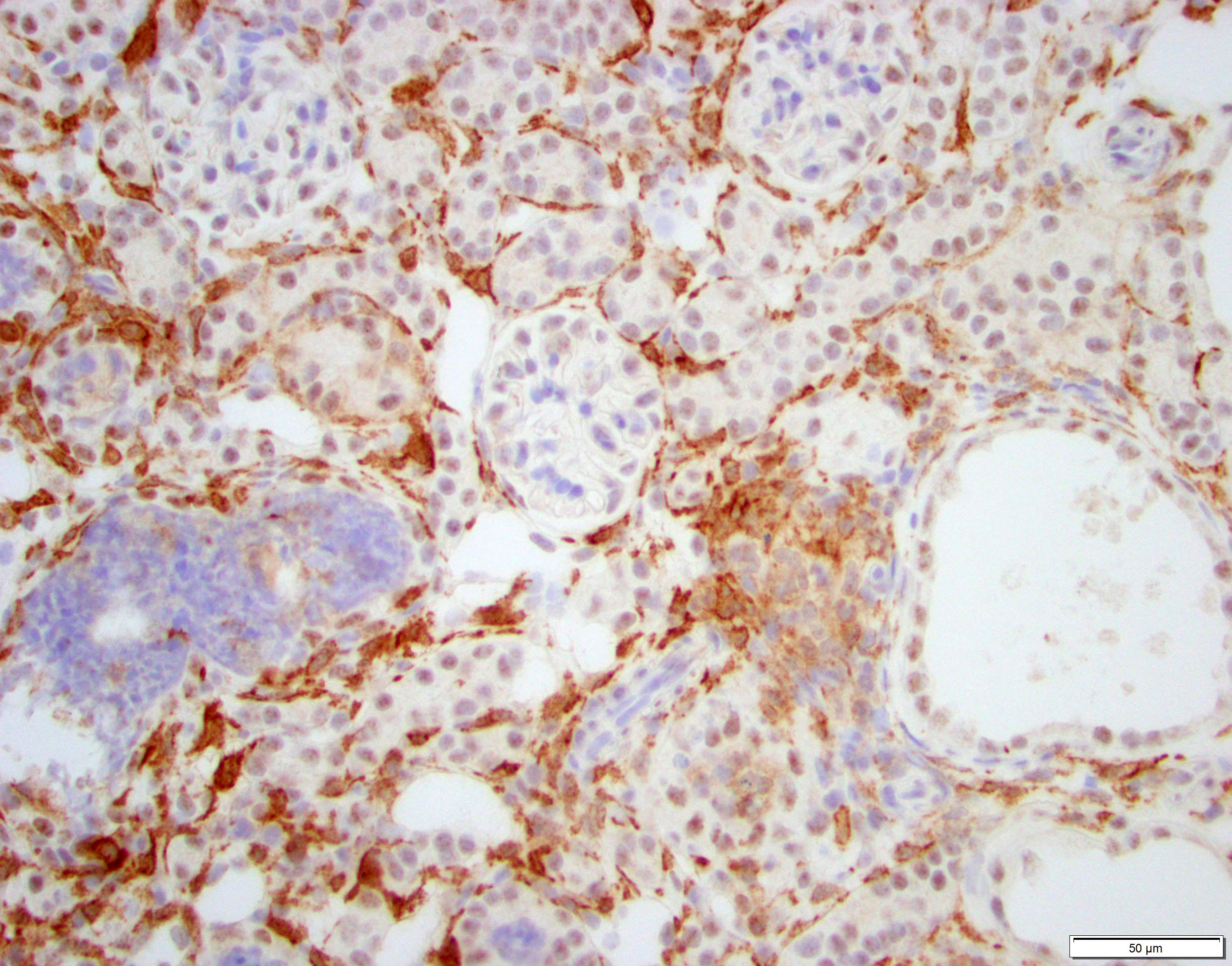

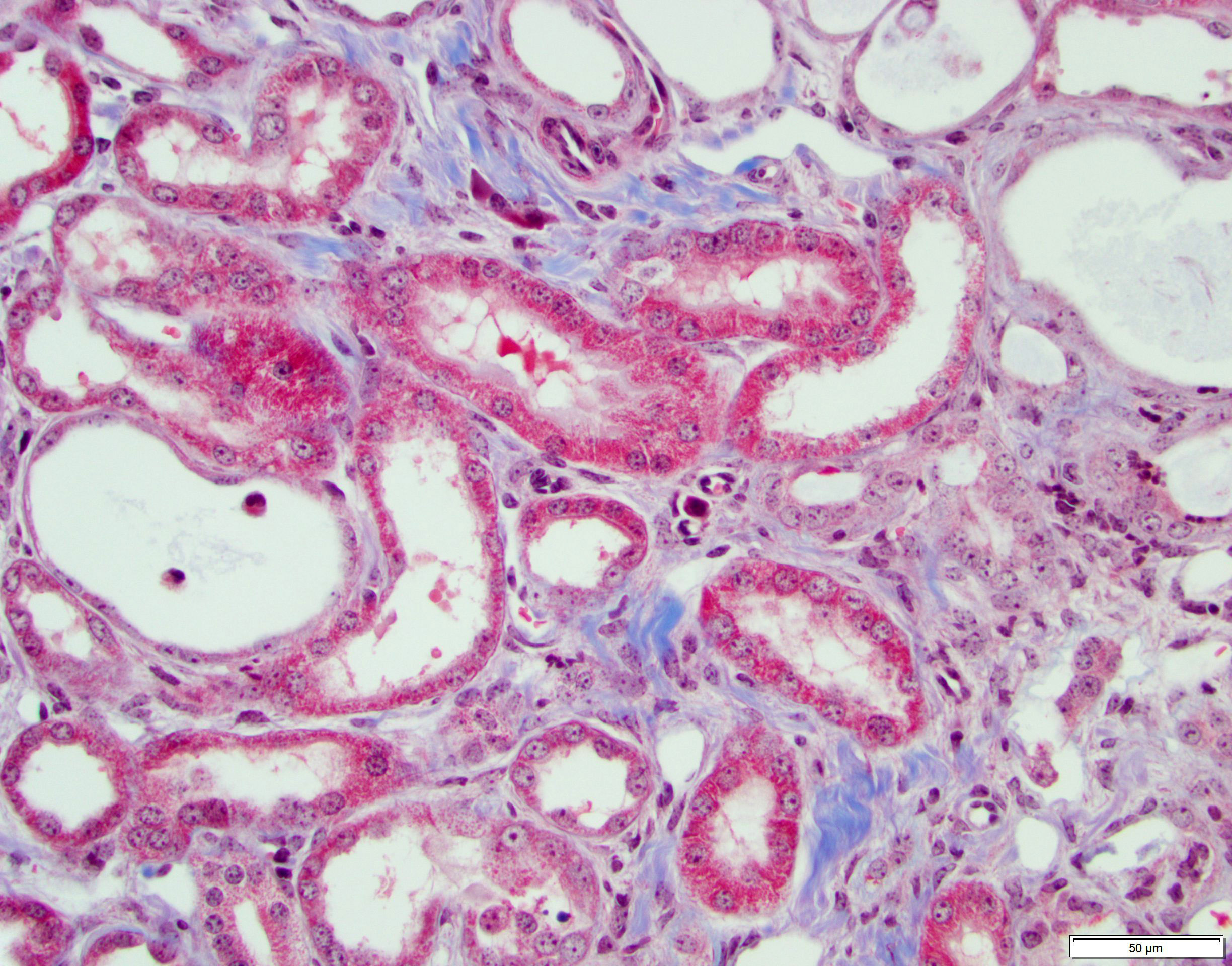

Kidney. The surface of the renal cortex is undulating with an irregular, scalloped appearance. Multifocally, renal tubules are dilated and have an attenuated epithelium. Dilated tubules are variably filled with an amorphous, pale basophilic material or abundant degenerate neutrophils, and less commonly contain brown to pale basophilic, spiculated, radiating birefringent crystalline material (2,8-dihydroxyadenine crystals) or dark basophilic coarsely granular material. Occasionally, crystal-filled tubules are surrounded by neutrophils, macrophages, and multinucleated giant cells. Often, Bowman’s spaces are mild to moderately dilated. Throughout the renal parenchyma, between tubules are streams of fibroblasts and collagen.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Liver: Microvesicular hepatopathy, moderate, acute, diffuse, with mild centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis.

Contributor’s Comment:

This mouse was administered 0.2% adenine in the diet for six weeks as part of a study on CKD. The animal was part of the control group and received no experimental manipulations except for adenine administration. The adenine diet model is a commonly utilized, well-established model of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in mice and rats.9 This diet induces a tubulointerstitial nephritis secondary to the metabolism of adenine in the kidneys. Adenine is metabolized by the enzyme xanthine dehydrogenase into 2,8-dihydroxyadenine (DHA), which precipitates in renal tubules, resulting in crystal formation.16 Injury of the tubules leads to tubulointerstitial inflammation which progresses over time to interstitial fibrosis.15 The model mirrors some of the clinicopathologic findings observed in human and animal CKD, including azotemia, hyperphosphatemia, elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH), and anemia.4,13,16 This model is well-established and reproducible in rodents, and while it has also been described in rabbits it is not well characterized in this species.5

Naturally occurring chronic renal disease in mammals typically results in non-regenerative anemia due to decreased production of erythropoietin, increased hepcidin, suppression of erythropoiesis, and decreased red blood cell lifespan.11 Studies of the adenine diet model of chronic kidney disease in rodents have demonstrated variation in the nature of the resulting anemia. Some studies employing the adenine diet model to study anemia of CKD have demonstrated no difference in absolute reticulocyte count between anemic and non-anemic animals, consistent with a non-regenerative response that is expected in a model of CKD-associated anemia.2, 17 However, others have demonstrated anemia with an increase in absolute reticulocyte count in rodents consuming a high-adenine diet.1 In the course of this study, we have observed an apparent regenerative response characterized by increased reticulocytes in adenine-treated mice. The mechanism for reticulocytosis in the face of overt renal insufficiency is not yet understood.

Rodents consuming a high-adenine diet begin to demonstrate evidence of renal injury, including reduction in creatinine clearance and intraluminal crystals, starting on day 3 after diet initiation.10 DHA crystals are brown, spiculated spheres which are birefringent in polarized light microscopy. Kidney lesions progresses as the diet is maintained, with tubular damage as the primary lesion. Crystals are primarily localized to proximal tubules and ascending limbs of the loops of Henle.10 Glomeruli are not directly injured by DHA nephropathy; however, dilation of the Bowman’s space is reported as a histologic finding of the adenine diet model.9 Direct tubular injury is accompanied by inflammation characterized primarily by macrophages which accumulate around injured tubules.10,15 Over time, tubular injury and inflammation progresses to interstitial fibrosis.

In humans, an inherited defect in purine metabolism leads to the accumulation of DHA and subsequent DHA nephrolithiasis. This autosomal recessive disorder results from a mutation of the gene encoding the enzyme adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (APRT), which normally catalyzes the formation of 5’-adenosine monophosphate (AMP) from adenine.3 Without this enzyme, adenine is instead metabolized to DHA which, as in the mouse model, precipitates within renal tubules and causes crystalline nephropathy. The mechanisms of the adenine diet in rodents closely recapitulate this human disease, making the adenine diet model a suitable preclinical model APRT deficiency.10 While the currently reported prevalence of APRT deficiency in human populations is quite low, this may represent an under-reporting of disease frequency.3 Biochemical stone analysis fails to differentiate DHA from uric acid, so stereomicroscopic analysis of urinary stones and infrared spectroscopy are preferable.3

DHA nephrolithiasis, likely caused by a similar genetic mutation, has been reported rarely in dogs.6, 8 There is a breed predisposition for primitive-type breeds such as malamutes and Native American Indian dogs. The genetic mutation identified in affected dogs is a missense mutation of the APRT gene.6 Clinically, affected animals have been documented to develop uroliths throughout the upper and lower urinary tract, which in some cases progress to obstructive renal failure. Treatment, as in humans, is administration of xanthine dehydrogenase inhibitors such as allopurinol.

Multiple drugs and toxins are capable of causing renal intratubular crystallization and subsequent damage. Ethylene glycol and melamine/cyanuric acid toxicosis are two examples of crystal nephropathy of veterinary importance. In contrast to DHA precipitation in the adenine diet model, ethylene glycol (EG) and melamine/cyanuric acid ingestion result in calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals or melamine-containing crystals, respectively. In EG toxicosis, EG metabolism results in the production of several end products, including oxalic acid. Oxalic acid binds to calcium within renal tubules and forms calcium oxalate crystals, which are directly cytotoxic and results in renal tubular epithelial cell death.12 The mechanism of melamine renal toxicity is less clearly elucidated, but co-administration of melamine and cyanuric acid appears necessary to induce crystal formation.14 Presence of melamine/cyanuric acid crystals within renal tubules is associated with tubular epithelial necrosis.7

Contributing Institution:

Laboratory of Comparative Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, The Rockefeller University, Weill Cornell Medicine. https://www.mskcc.org/research/ski/core-facilities/comparative-medicine-pathology-0

JPC Diagnoses:

Kidney, cortex: Tubular degeneration, necrosis, and regeneration, chronic, diffuse, marked, with intratubular and interstitial crystals, granular and hyaline casts, mineralization, and interstitial fibrosis.

JPC Comment:

Conference 15 was moderated by the globally renowned Dr. Cory Brayton, a top expert in mouse pathology from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. This first case is one that has never been seen before in the WSC, and the contributor provided an outstanding write-up to accompany it.

Conference discussion covered multiple topics, some of which are covered in the provided write-up. Dr. Brayton spoke on numerous important features in the evaluation of a case such as this. These included knowing the history of the affected animal, understanding common background lesions in particular mice strains, and where the discerning pathologist should look for mineral in the kidneys (within tubules, in tubular basement membranes, and within vascular tunics). Additionally, emphasis was placed on ensuring one takes the time to evaluate the presence or absence of tubular degeneration, regeneration, and/or atrophy (all of which were present in this case as tubular damage is the primary lesion of adenine nephritis), and the histologic appearance of crystals. There was some speculation amongst participants on the presence of tubular regeneration in this slide, which is typically characterized by hypercellular, more basophilic tubules with a high N:C ratio in their epithelial cells. Ultimately, the presence of regenerative tubules was agreed upon, although it took the more experienced eyes in the room to point them out to less experienced participants. The Non-Neoplastic Lesion Atlas and Mouse INHAND guide both have excellent examples of tubular regeneration for those that may be unfamiliar.6,16 There was discussion on how to discern atrophy of brown fat after one participant questioned if the adipose tissue in the slide was atrophic or just brown fat (it was brown fat), which is challenging, but best assessed around the salivary gland in mice. Atrophic brown fat has the appearance of being its own unidentifiable organ due to the degree of consolidation; don’t be fooled!

There was significant discussion on the complete blood count (CBC) of this case, which demonstrated a microcytic, hypochromic, regenerative anemia. This struck conference participants as odd since most chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients have a normochromic, non-regenerative anemia due to the lack of erythropoietin production from the damaged kidneys. Additionally, the reticulocyte count was reportedly elevated, which should have resulted in macrocytosis rather than microcytosis. The blood chemistry profile of this animal also revealed an elevated BUN, mildly elevated creatinine, mildly elevated globulin, and mild hyperphosphatemia. While these findings indicate an azotemia was present, the elevated globulin and phosphorus levels may suggest that this animal was dehydrated and had a pre-renal azotemia rather than renal azotemia. Urine specific gravity (USG) and total protein (TP) measurements would have helped tease this out further, but conference participants acknowledge that there are limitations in some cases. Additionally, most laboratories have their own reference ranges for different strains of mice that often differ from those used in other labs, so conference participants assumed that this contributor’s lab knows their reference ranges in this particular mouse strain and deferred to their data in drawing these conclusions. It certainly made for excellent discussion!

While the history of an adenine diet in this mouse made for a straightforward diagnosis, other possible causes of brown crystals in kidneys include melamine cyanuric acid, bilirubin, calcium carbonate, and ammonium biurate, to name the most pertinent. Additional causes of proximal convoluted tubular (PCT) damage in other species that win honorable mentions from conference discussion include aminoglycosides (foals and humans), oxalates (ruminants), monensin (horses and poultry), and ethylene glycol (dogs, cats, and humans).

Lastly, wrapping up discussion was a quick mention by Dr. Brayton on the potential for Mouse Kidney Parvovirus (MKPV) to confound CKD studies in mice. In a recent study, it was found that MKPV-infected mice on an adenine diet for CKD study had more interstitial nephritis at one month and two months of diet consumption compared to those that did not have MKPV.15 They also had less interstitial fibrosis at 2 months comparatively.15 This virus, which makes for some stunning histologic images, by the way (please see the cover of the new Barthold book), can complicate grading and evaluation of CKD-associated lesions in mice that are infected during the study period and, as such, lesions should be interpreted with caution and contexts.

References:

- Akchurin O, Patino E, Dalal V, et al. Interleukin-6 contributes to the development of anemia in juvenile CKD. Kidney International Reports. 2019;4:470-483.

- Akchurin O, Sureshbabu A, Doty SB, et al. Lack of hepcidin ameliorates anemia and improves growth in an adenine-induced mouse model of chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(5):F877-F889.

- Bollee G, Harambat J, Bensman A, Knebelmann B, Daudon M, Ceballos-Picot I. Adenine Phosphoribosyltransferase Deficiency. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1521-1527.

- deFrutos S, Luengo A, Garcia-Jerez A, et al. Chronic kidney disease induced by an adenine rich diet upregulates integrin linked kinase (ILK) and its depletion prevents the disease progression. BBA Molecular Basis of Disease. 2019;1865:1284-1297.

- Florens N, Lemoine S, Pelletier CC, Rabeyrin M, Juillard L, Soulage CO. Adenine Rich Diet Is Not a Surrogate of 5/6 Nephrectomy in Rabbits. Nephron. 2017;135:307-314.

- Frazier KS, Seely JC, Hard GC, et al. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse urinary system. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40(4 Suppl):14S-86S.

- Furrow E, Pfeifer RJ, Osborne CA, Lulich JP. An APRT mutation is strongly associated with and likely causative for 2,8-dihydroxyadenine urolithiasis in dogs. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;111(3):399-403.

- Hau AK, Kwan TH, Li PK. Melamine Toxicity and the Kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:145-250.

- Houston DM, Moore AE, Mendonca SZ, Taylor JA: 2,8-Dihydroxyadenine uroliths in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;241:1348–1352.

- Jia T, Olauson H, Lindberg K, et al. A novel model of adenine-induced tubulointerstitial nephropathy in mice. BMC Nephrology. 2013;14:116.

- Klinkhammer BM, Djudjaj S, Kunter U, et al. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Kidney Injury in 2,8-Dihydroxyadenine Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:799-816.

- Lippi I, Perondi F, Lubas G, et al. Erythrogram patterns in dogs with chronic kidney disease. Vet Sci. 2021;8(7):123.

- McMartin K. Are calcium oxalate crystals involved in the mechanism of acute renal failure in ethylene glycol poisoning? Clinical Toxicology. 2009;47(9):859-869.

- Rahman A, Yamazaki D, Sufiun A, et al. A novel approach to adenine-induced chronic kidney disease associated anemia in rodents. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2): e0192531.

- Ritter AC, Arbona RRJ, Livingston RS, Monette S, Lipman NS. Effects of Mouse Kidney Parvovirus on Pharmacokinetics of Chemotherapeutics and the Adenine Model of Chronic Kidney Disease. Comp Med. 2023;73(2):153-172.

- Sands JM, Verlander JW. Anatomy and physiology of the kidneys. In: Toxicology of the Kidney, 3rd ed (Tarloff JB, Lash LH, eds). CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 2005;3-56.

- Son JY, Kang YJ, Kim KS, et al. Evaluation of Renal Toxicity by Combination Exposure to Melamine and Cyanuric Acid in Male Sprague-Dawley Rats. Toxicol. Res. 2014;30(2):99-107.

- Tamura M, Aizawa R, Hori M, Ozaki H. Progressive renal dysfunction and macrophage infiltration in interstitial fibrosis in an adenine-induced tubulointerstitial nephritis mouse model. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;131:483-490.

- Tani T, Orimo H, Shimizu A, Tsuruoka S. Development of a novel chronic kidney disease mouse model to evaluate the progression of hyperphosphatemia and associated mineral bone disease. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:2233.Thibodeau JF, Simard JC, Holterman CE, et al. PBI-4050 via GPR40 activation improves adenine-induced kidney injury in mice. Clin Sci (Lond). 2019;133(14):1587-1602.