Signalment:

Gross Description:

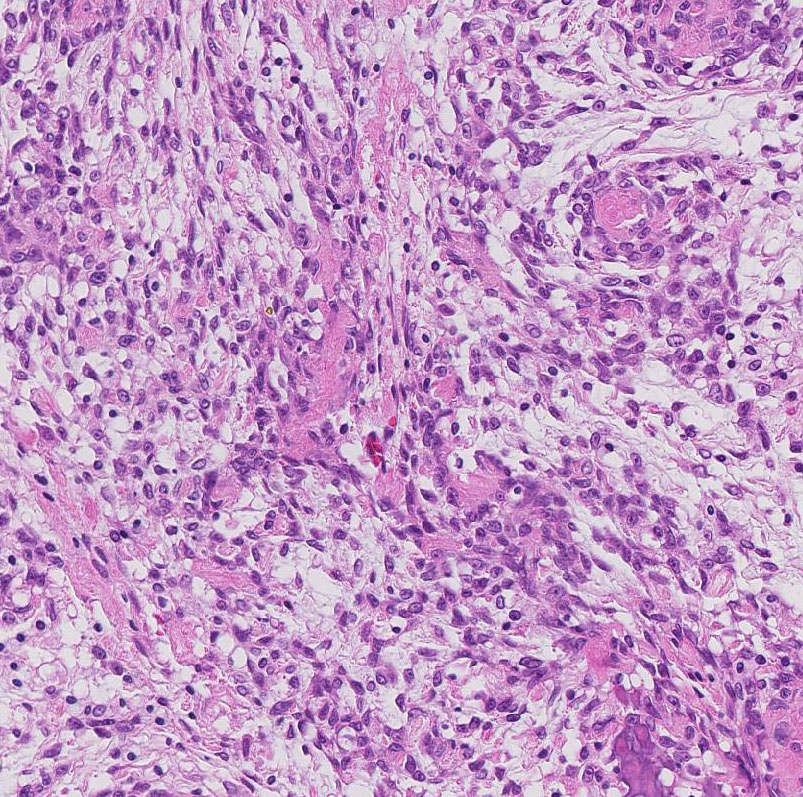

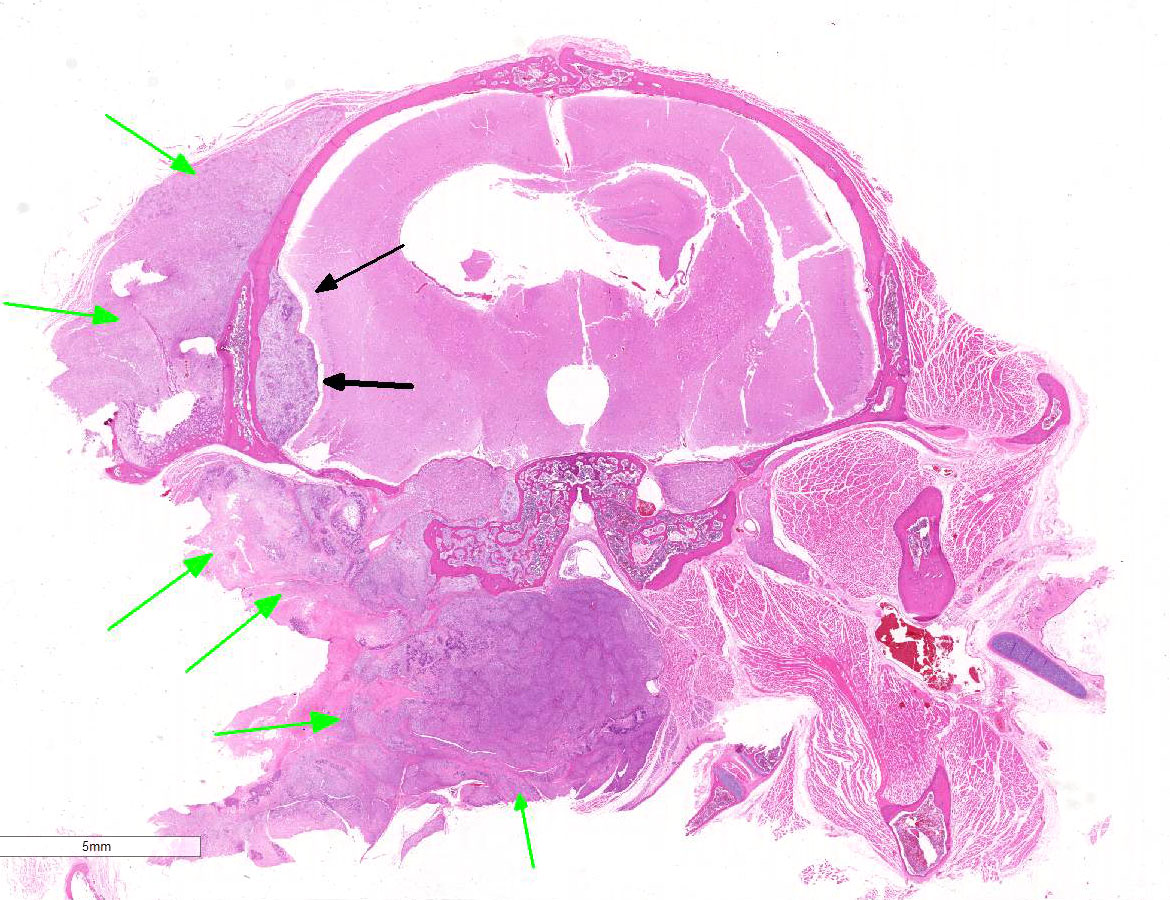

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Although osteosarcoma accounts for up to 85% of malignant bone tumors in dogs and 70% in cats,2 the occurrence in African hedgehogs is unusual. In dogs, osteosarcomas can be subclassified according to the predominant histologic pattern into six different categories: poorly differentiated, osteoblastic, chondroblastic, fibroblastic, teleangiectatic and giant-cell rich osteosarcoma. This classification scheme is an adaptation of a system developed for use in human medicine. Osteoblastic osteosarcoma is the most common subtype, and it can be further sub-classified into nonproductive and productive, based on the tumor bone produced. According to this classification, this osteosarcoma would be classified as a productive osteoblastic osteosarcoma. 2

Additionally, intracranial, extracranial, and skull base neoplasms often compress the facial nerve and may result in facial paralysis.5 In this case, cranial nerve involvement can be seen in some slides. Nerves are clearly compressed and surrounded by the neoplastic tissue, leading to Wallerian degeneration. Wallerian degeneration is a process that occurs when a nerve fiber is cut or crushed, leading to axonal separation from the neuronal cell body which degenerates distal to the injury. 9

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

As mentioned by the contributor, neoplasia is an extremely common antemortem and postmortem finding in the African hedgehog. However, mesenchymal neoplasms, such as in this case, are relatively uncommon with an incidence of only about 4% at necropsy.1,3,8 Epithelial neoplasms of the integument are the most common type, followed by round cell tumors. Osteosarcoma is the most common mesenchymal neoplasm reported in African hedgehogs.3

In dogs and cats, osteosarcoma is characterized by rapid progression and early metastasis to the lungs, resulting in short survival times and high mortality rate.2 This aggressive biologic behavior is similar in reported cases of osteosarcoma in African hedgehogs.1,3,8 The contributor describes six different categories of osteosarcoma in dogs based on the predominant histologic pattern. These include:

1. Poorly differentiated:

- o Variation in cell size from small primitive mesenchymal to large and pleomorphic undifferentiated cells

- o Identification depends on presence of unequivocal tumor osteoid

- o Highly aggressive and associated with pathological fractures.

- o Anaplastic osteoblasts; variable amounts of basophilic cytoplasm, and hyperchromatic, eccentric nuclei

- o Further subclassified as nonproductive or productive based on presence or absence of tumor bone production

- o Productive osteoblastic OSA is the most common subtype in dogs

- o Neoplastic cells produce both chondroid and osteoid matrices

- o Interlacing bundles of spindle cells resembling fibrosarcoma that produce osteoid or bone

- o Solid areas and large bloodfilled spaces lined by malignant osteoblasts that occasionally form spicules of osteoid

- o Resembles hemangiosarcoma, but is immunonegative for factor VIII and CD31

- o Most malignant classification with least favorable prognosis.

- o Tumor giant cells predominate with nuclear atypia and a high mitotic rate

- o Must be differentiated from the benign giant cell tumor of bone2

The conference moderator cautioned participants that histologic classification of osteosarcoma is often complicated by their heterogeneous nature, as several microscopic patterns are often evident within a single neoplasm. Regardless of classification, the prognosis for all subtypes of canine central osteosarcoma is considered poor. The conference moderator also mentioned different grading systems for osteosarcoma based on nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic index, necrosis, multinucleated cells, the amount of tumor matrix, and vascular invasion. Unfortunately, no histologic grading system has gained widespread acceptance by veterinary pathologists due to marked variation in histomorphology of the neoplastic cells within different regions of the same tumor.2

References:

2. Craig LE, Dittmer KE, Thompson KG. Bones and joints. In: Maxie MG ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:110-116.

3. Heatley J, Mauldin G, Cho D. A Review of Neoplasia in the Captive African Hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris). Semin Avian Exot Pet. 2005; 14:182192.

4. London C, Dubilzeig R, Vail D, Ogilvie G, Hahn K, Brewer W, DVM; Hammer A, O'Keefe D, Chun R, McEntee M, McCaw D, Fox L, Norris A, Klausner J. Evaluation of dogs and cats with tumors of the ear canal: 145 cases (1978-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996; 208: 1413-18.

5. Marzo S, Leonetti J, Petruzzelli G. Facial paralysis caused by malignant skull base neoplasms. Neurosurg Focus. 2002; 12 (5): 1-4.

6. Peauroi J, Lowenstine L, Mun R, D. Wilson. Multicentric Skeletal Sarcomas Associated with Probable Retrovirus Particles in Two African Hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris). Vet Pathol. 1994; 31:481-484.

7. Phair K, Carpenter J, Marrow J, Andrew, G, Bawa. Management of an Extraskeletal Osteosarcoma in an African Hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris). Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 2011; 20 (2): 15115.

8. Rhody J, Schiller C. Spinal Osteosarcoma in a Hedgehog with Pedal Self-Mutilation. Vet Clin Exot Anim. 2006; 9: 625631.

9. Zachary JF. Nervous System. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary 6 Disease. 5th ed. p.p. 959 St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012.