Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 10, Case 1

Signalment:

8-year-old female spayed Wire-Haired Terrier (Canis familiaris)History:

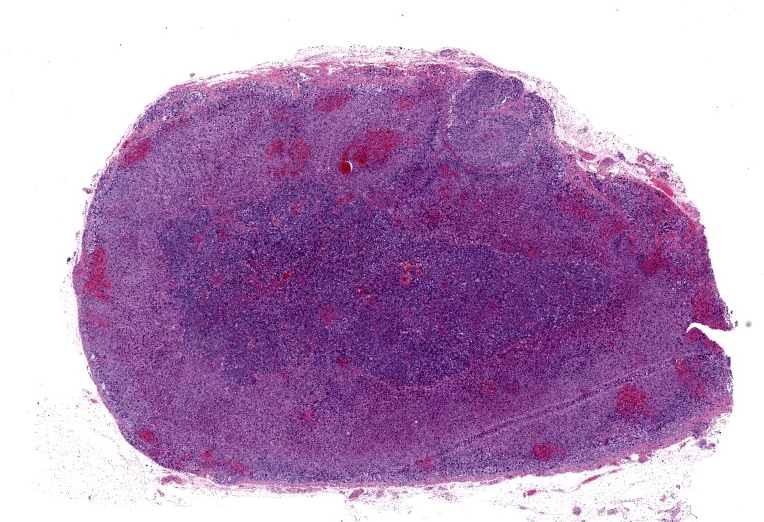

Gross Pathology: The dog had moderate amounts of body fat stores and normal muscle mass. The thoracic cavity contained approximately 40 ml of red-tinged, watery fluid. The lungs were mottled dark and bright red, heavy, wet, and non-collapsed; abundant pink foamy fluid oozed from the cut surface. The heart was rounded; the left ventricular free wall was 22 mm thick, and the right ventricular free wall was 5 mm thick (left ventricular hypertrophy). The left atrium was mildly dilated. The leaflets of the mitral valve were shrunken, thickened, and nodular (myxomatous valvular degeneration or endocardiosis). The right ventricle had multifocal, slightly raised, areas of subendocardial hemorrhage. In the abdominal cavity, the stomach contained moderate amounts of clear mucoid material. The intestinal tract showed multifocal areas of mucosal congestion. The pancreas had a diffuse nodular surface (nodular hyperplasia). The spleen had multifocal, small, dark-red nodules scattered throughout the surface. Multifocal areas of mucosal hemorrhage were noted in the trigone of the urinary bladder. The brain showed multifocal areas of meningeal hemorrhage over the occipital lobes. No gross abnormalities were observed in the rest of the carcass.Laboratory Results:

N/A>Microscopic Description:

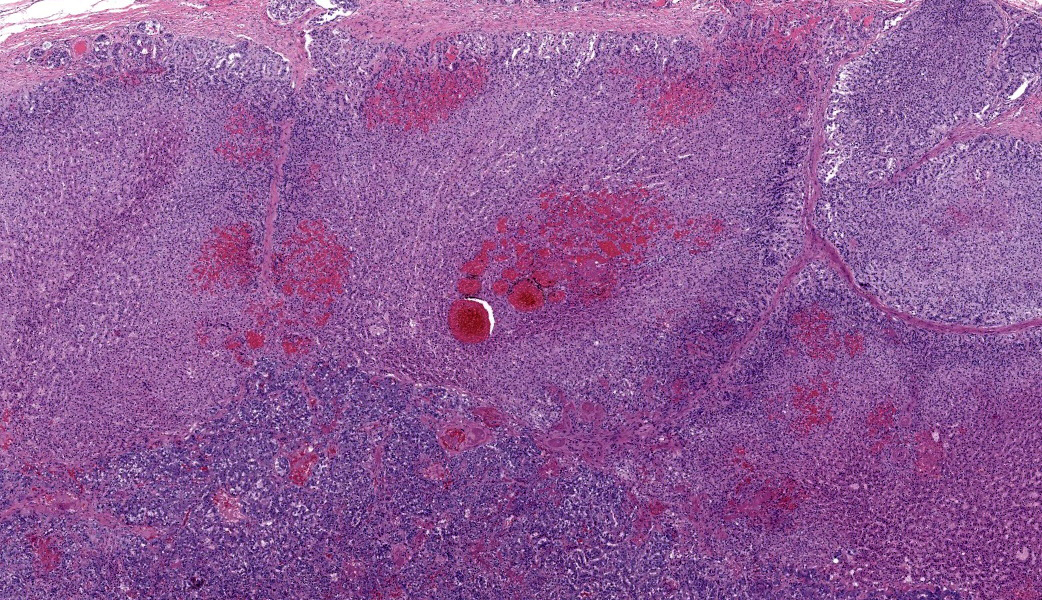

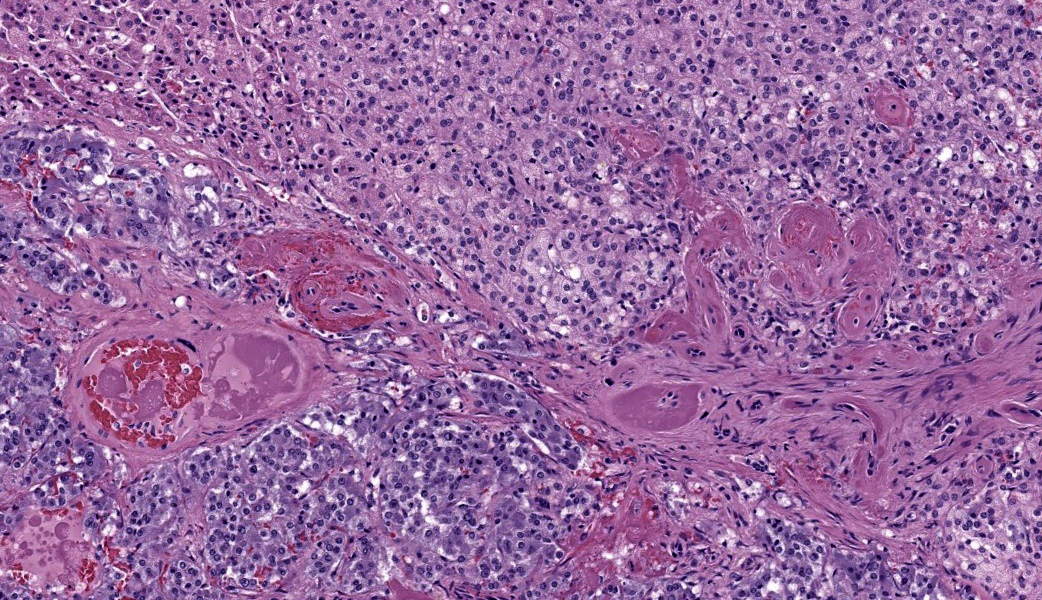

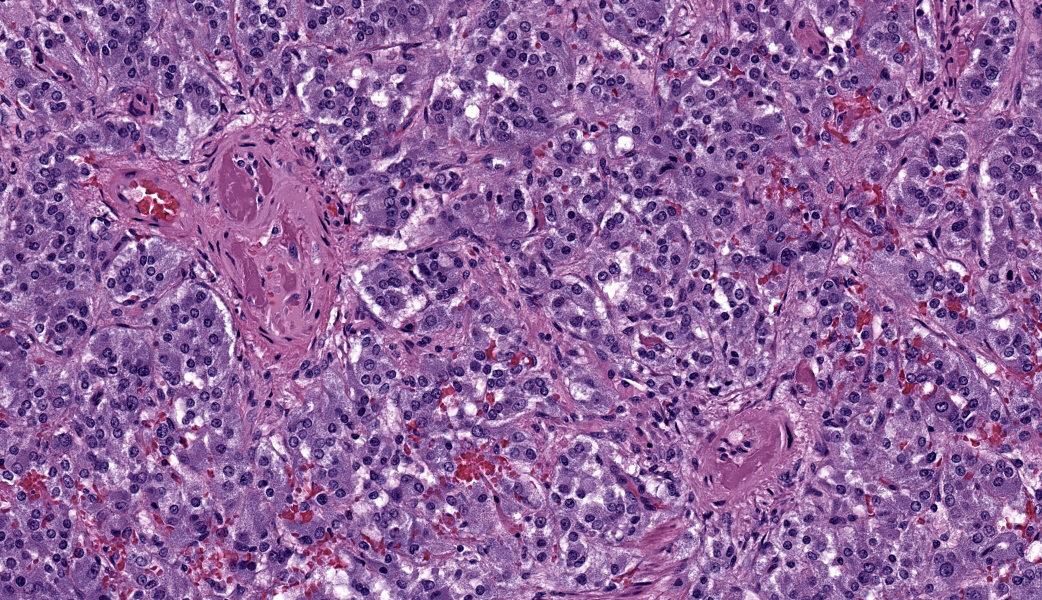

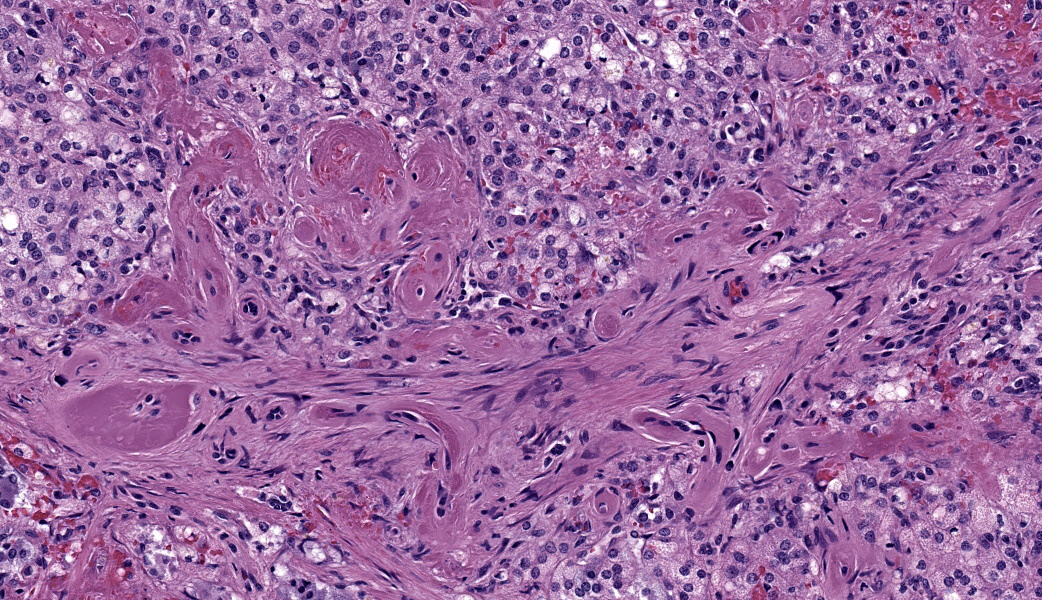

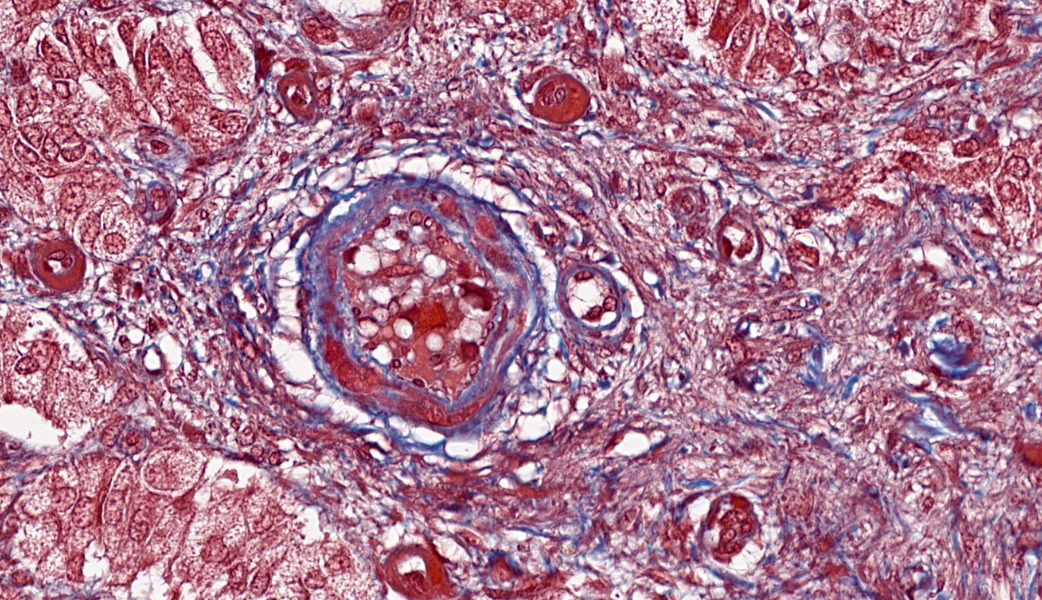

Adrenal glands: Multifocally, the small arteries and arterioles within the cortex and medulla show marked thickening of their walls, and narrowing or obliteration of their lumen, by intramural deposition of plasma proteins (consistent with hyaline arteriolosclerosis). Some vessels show intramural laminar deposits of plasma proteins (onion-skinning). Many sinusoidal vessels in the medulla are occluded by fibrin thrombi and are frequently effaced by hyaline material.Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Adrenal glands: Multifocal hyaline arteriolosclerosis.Condition: Hypertensive vasculopathy. Other diagnoses (tissues not included in the submission):

Kidneys: Glomerulonephritis, diffuse, global, severe, subacute to chronic.

Eye globes: Bilateral retinal detachment with hyaline arteriolosclerosis, subretinal hemorrhage, and retinal atrophy (secondary glaucoma).

Heart, brain (choroid plexus), and spleen: Multifocal hyaline arteriolosclerosis.

Heart, right ventricle: Myocardial infarction, multifocal, acute.

Heart, mitral valve: Myxomatous valvular degeneration (endocardiosis).

Heart: Left ventricular hypertrophy.

Stomach: Mucosal necrosis and mineralization (uremic gastropathy).

Contributor's Comment:

Arteriolosclerosis is defined as ?hardening of small arterial vessels? and consists of a group of arteriolar lesions often characterized as either predominantly hyaline or predominantly hyperplastic.4 Hyaline degeneration (intimal hyalinosis), such as that seen in this case, refers to the histologic observation of amorphous, brightly eosinophilic material in vessel walls. This material stains magenta with periodic acid-Shiff (PAS) and often appears glassy.4,5 It is a common vascular lesion resulting from accumulation of various serum plasma components in the subendothelial space and often extends into the media.5 This lesion can be seen in various conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS).5 Thickening of the arteriolar wall due to accumulation of plasma proteins may lead to luminal narrowing and local ischemia.4In humans, the most common inciting cause is hypertension. The pathogenesis in domestic animals is often not confirmed; most of the postmortem findings in the present case were consistent with systemic hypertension secondary to renal disease.4 Although both primary and secondary hypertension have been reported in dogs, the latter is more common.4

Renal disease, such as in this case, is likely the most common cause of hypertension in dogs; however, since renal disease can be both the cause and consequence of systemic hypertension, it can be challenging to discern whether hypertensive vascular lesions are the result of primary or secondary hypertension.4 Primary hypertensive lesions can lead to renal hypoperfusion, which activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, leading to more hypertension.4 On the other hand, chronic renal disease often results in unbalanced excretion/retention of sodium and water, which leads to blood volume expansion and secondary hypertension.4 Regardless of the initial inciting cause, hypertension becomes self-perpetuating as medial hypertrophy and hyalinization of arteries lead to hypoperfusion of organs, such as the kidney, and promotes additional hypertension and vascular damage.4 Other lesions associated with secondary hypertension include hypertensive retinopathy with retinal detachment and left ventricular hypertrophy, which were also seen in this case.

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Pathology ? Western College of Veterinary Medicine (https://wcvm.usask.ca/departments/vet-pathology.php)JPC Diagnoses:

Adrenal gland, arterioles: Fibrinoid necrosis, chronic, diffuse, moderate, with fibrin thrombi and hemorrhage.JPC Comment:

Conference 10 was moderated by the steadfast former Training Officer (and former WSC Coordinator) of the JPC, LTC Sarah Cudd! She chose to focus her conference cases on board-worthy entities and critical concept discussions for residents. This first case was challenging for participants and served as an excellent segway into a review of hypertension and atherosclerosis.Discussion began with the differences between arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, meaning ?hardening of arteries?, is characterized as a proliferative and degenerative arterial change in the absence of inflammation with thickening of the tunicas media and intima. Smooth muscle cells from the tunica media migrate to the tunica intima under the influence of platelet-derived growth factor PDGF), which stimulates smooth muscle cell migration and growth by binding to its receptors on the muscle cell surface. This triggers a series of internal signaling pathways that promote cell proliferation and migration, such as the PI3K/Akt/mTOR cascade. This pathway ultimately activates transcription factors that cause changes in gene expression and cell cycle progression via the activation of receptor tyrosine kinases. Atherosclerosis, on the other hand, is a subset of arteriosclerosis and is characterized histologically by degenerative fatty changes with cholesterol clefts, foam cells (which can be either macrophages or smooth muscle cells), and extra cellular lipid within arterial walls. Atherosclerosis is the most common type of arteriosclerosis in humans and is rarely seen in dogs except in cases of hypothyroidism or diabetes mellitus that contribute to hyperlipidemia. Miniature Schnauzers are genetically predisposed to atherosclerosis due to idiopathic hyperlipoproteinemia. Watanabe rabbits are also predisposed to and used as a research model for atherosclerosis due to a genetic mutation in their LDL receptors.

So, what about arteriolosclerosis? How does that compare to arteriosclerosis? Arteriosclerosis usually affects large arteries, such as the abdominal aorta in horses, ruminants, and carnivores, and is an aging change. Arteriolosclerosis affects small arterioles and is largely due to endothelial damage secondary to hypertension. There are two types of arteriolosclerosis: hyaline and hyperplastic. The hyaline form is considered the acute stage. In the hyperplastic form, proliferation of smooth muscle cells within the tunica intima, coupled with concentric fibrosis, can lead to a characteristic ?onion-skinning? appearance of the affected vessels with chronicity.

Wrapping up conference discussion was a review of primary vs. secondary hypertension, which the contributor did an excellent job of covering in their comment. Hypertension causes hyaline arteriolosclerosis by causing endothelial damage, which then forces serum proteins from the blood out into the arteriolar walls where they accumulate and form deposits. This is traditionally referred to as ?fibrinoid necrosis?, and conference participants elected to use this term for the morphologic diagnosis. Additionally, the damage to the vessel walls from the increased pressure causes them to become tortuous and stimulates them to thicken and harden via smooth muscle proliferation and fibrosis as previously mentioned, reducing their elasticity and narrowing the lumen. This impairs blood flow and may result in thrombosis.3 In cases of hypertension, the most common presenting clinical sign in affected animals is acute blindness secondary to hypertensive retinopathy.

With renal disease being one of the key drivers of hypertension in many species, a quick review of this pathogenesis is warranted. Renal disease causes secondary hypertension primarily through fluid retention. Injured kidneys are less able to remove excess fluid and sodium, which leads to an increased blood volume and, subsequently, an increased blood pressure. In primary hypertension leading to renal hypoperfusion, there is activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), which unfortunately only exacerbates the problem.

The RAAS first came under study in 1898 with the discovery of renin by Drs. Tigerstedt and Bergman when they found that renal extracts produced a vasopressor effect on tissue.1 It wasn?t until many years later that angiotensin and aldosterone were discovered and described, ultimately resulting in the RAAS we understand today.1 RAAS becomes activated following an initial drop in blood pressure, during which less sodium is flowing through the kidneys.1,2,3 The macula densa cells within the juxtaglomerular apparatus of the kidneys detect lower sodium levels within the proximal convoluted tubules and subsequently release prostaglandin E2 (PGE2).2 PGE2 then acts on juxtaglomerular cells within the afferent arterioles of the kidneys and causes them to release renin. From there, renin stimulates conversion of liver-produced angiotensinogen in the blood to angiotensin I within the kidneys.2 Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) then converts angiotensin I to active angiotensin II, which is a potent vasoconstrictor. Constriction of blood vessels subsequently stimulates the adrenal cortices to synthesize and release aldosterone, which then signals the kidneys to retain water and sodium from the distal convoluted tubules and collecting ducts, thereby increasing both blood volume and blood pressure.2,3

Angiotensin II also stimulates secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the posterior pituitary, which increases the glomerular filtration rate by increasing water resorption from the kidneys.2 It does this via the insertion of aquaporin-2 channels in the collecting duct.2,3 It?s not difficult to see from here how activation of RAAS makes a hypertensive problem worse. When coupled with a chronic arteriolosclerosis, it has been suggested that autoregulation of these systems becomes even further impaired and may result in additional increased systemic pressure to the glomerulus, further perpetuating renal disease and contributing to the vicious cycle of hypertension.2

References:

- Basso N, Terragno NA. History about the discovery of the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension. 2001;38(6):1246-9.

- Manrique C, Lastra G, Gardner M, Sowers JR. The renin angiotensin aldosterone system in hypertension: roles of insulin resistance and oxidative stress. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(3):569-82.

- Nair R, Vaqar S. Renovascular Hypertension. [Updated 2023 May 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. ? 6th Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016: 59-60.

- Olson JL. Hyaline arteriolosclerosis: New meaning for an old lesion. Kidney International. 2009;63:1162?1163.