Signalment:

14-year-old, intact female, Thoroughbred, equine (

Equus caballus)The horse had a two day history of colic. Exploratory surgery revealed a 12 cm in diameter mass cranial to the left kidney which was not surgically respectable. Euthanasia was elected after a rapid decline in health post surgically that was unresponsive to medical management.

Gross Description:

10 cm of the cranial mesenteric artery, immediately distal to the ostium, was dilated 3 cm and thickened (6 mm). The vessel was partially occluded by a 3.5 cm long red to purple, friable coagulum (thrombus) that was tenaciously adhered to the intimal surface. The intima was diffusely rough and granular.

Histopathologic Description:

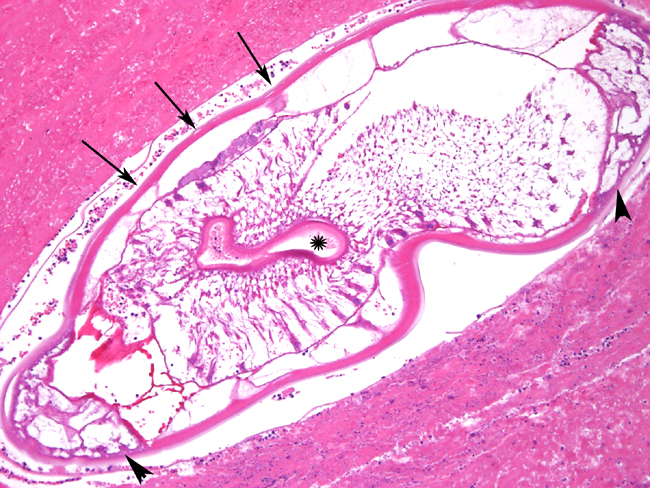

The arterial lumen is occluded by an eosinophilic, amorphous coagulum (thrombus) containing alternating layers of free erythrocytes, intact and degenerate neutrophils, and necrotic debris (lines of Zahn) and multiple 1-2 mm cross sections of nematodes. The nematodes have a bright eosinophilic, thick, smooth, cuticle with lateral cords and platymyarian musculature surrounding a central digestive tract. The thrombus adheres to and blends in with the vessel wall. The endothelium is mostly absent and the internal elastic lamina is disrupted, fragmented, and coiled. The tunica intima is diffusely thickened by proliferative immature fibrous connective tissue which also penetrates the tunica media and extends to and expands the adventitia, with separation and individualization of smooth muscle fibers. The intima is diffusely infiltrated by many neutrophils and relatively fewer eosinophils extending in from the lumen in declining numbers to the subjacent tunica media. The deep tunica media and adventitia is punctuated by variably sized aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells admixed with foamy and hemosiderin-laden macrophages and rare clusters of neutrophils.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cranial mesenteric artery: Arteritis, chronic, severe, suppurative and lymphoplasmacytic.Â

Cranial mesenteric artery: Thrombus, acute with intralesional nematodes.

Lab Results:

Clinical pathology abnormalities at surgery:

Neutrophils = 16.1X10

3/ul (5.5-12.0) Lymphocytes = 0.79X10

3/ul (1.5-5.0)

Total protein = 8.1 g/dL (5.5-7.5) Serum globulin = 4.9 g/dL (2.6-4.0)

Sodium = 133 mEq/L (137-148) Chloride = 90 mEq/L (98-110)

Potassium = 1.9 mEq/L (2.9-5.3) Sodium/Potasium ratio = 70 (28-36)

Glucose = 133 mg/dL (71-100) Alk phos = 262 U/L (45-239)

Total bilirubin = 2.7 mg/dL (0.6-2.6) CPK = 1507 U/L (120-350)

SDH = 15.9 U/L (0.2-7.0)

All other values were within normal limits.

Condition:

Strongylus vulgaris

Contributor Comment:

Strongylus vulgaris is one of three species of the genus Strongylus which occur the horse and is considered to be the most damaging to the host

6. The life cycle involves the ingestion of third-stage larvae which penetrate the mucosa and submucosa of the small and large intestines. Seven days after ingestion most of the larvae have molted to become fourth-stage larvae which then penetrate the submucosal intestinal arterioles and migrate along the intima, eventually reaching the mesenteric artery. Migrations during the fourth stage of development lead to the gross lesions which range from tortuous intimal tracts to thrombotic lesions, often referred to as verminous aneurisms, and arteritis

6 . The small bulging tracks containing larvae, and the associated endothelial damage serves as a nidus for the development of thrombi. The arteritis and fibrosis of the arterial wall is attributed to both the disruption of the internal elastic lamina and the inflammatory response induced by the larvae. Larvae are generally found in intimal thrombi of the artery and rarely in the tunica media and adventitia

7. Research has shown that the curvature of the vessels, not the direction of blood flow, influences migration patterns and larva prefer to migrate longitudinally along vessels

1, which accounts for the localization of the larvae in the mesenteric artery. Migration into the aorta is very infrequent, presumably because the cranial mesenteric artery branches at a right angle from the aorta. The larvae molt to the fifth stage after 3-4 months and return to the cecum and colon, where they develop into adults in two months and begin reproduction.Â

S. vulgaris is thought to cause colic via thromboembolic obstruction of the cranial mesenteric artery (with secondary infarction of the bowel), reduced blood flow to the branches off the cranial mesenteric artery, interference with innervation due to pressure on abdominal autonomic plexuses, or disruption of ileal motility by toxic products generated from degenerating larvae

3.Â

The prevalence of cranial mesenteric arteritis due to

S. vulgaris in horses has ranged from 80% in 1937 to 98% in 1991

2 with a dramatic decline to 6% in the late 1990s

5 The drastic decrease in incidence has been attributed to the instigation of effective anthelmentic programs.

JPC Diagnosis:

Artery: Arteritis, chronic-active, multifocal to coalescing, moderate with marked diffuse transmural fibrosis, mural fibrin thrombus and intraluminal larval strongyles, Thoroughbred (

Equus caballus), equine.

Conference Comment:

Strongylus vulgaris is the only large strongyle that is known to undergo portions of its development within the equine arterial system.

6 The other two large strongyles that are known to commonly affect horses are

S. edentates and

S. equines. S. edentates normally migrates via the portal system to the liver, molts to L

4 within the liver parenchyma, and then returns to the cecum via hepatic ligaments.Â

S. equines migrates through the peritoneal cavity to the liver then the pancreas and re-enters the cecum and right ventral colon via direct penetration.

2

Other vascular parasites include:

- Blood flukes of mammals and birds Schistosoma sp., Heterobilharzia sp., Orientobilharzia sp.

- Onchocerca sp. within the walls of the aorta of cattle, buffalo and goats

- Dirofilaria immitis heartworm of dogs, cats, sea lions, muskrats

- Brugia sp. tropical parasite of dogs and cats

References:

1. Aref S: A random walk model for the migration of

Strongylus vulgaris in the intestinal arteries of the horse. The Cornell Veterinarian 72:64-75, 1982

2. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK: Alimentary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 4th ed., vol. 2, pp. 247-248. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007

3. Drudge JH, Lyons ET: Large strongyles. recent advances. Veterinary Clinics of North America. Equine Practice 2:263-280, 1986

4. Gelberg HB: Alimentary system. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, eds. McGavin MD, Zachary JF, 4th ed., pp. 356-357. Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2007

5. Lyons ET, Swerczek TW, Tolliver SC, Bair HD, Drudge JH, Ennis LE: Prevalence of selected species of internal parasites in equids at necropsy in central kentucky (1995-1999). Vet Parasitol 92:51-62, 2000

6. Maxie, MG, Robinson WF: Cardiovascular system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 4th ed., vol. 3, pp. 89-91. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007

7. Morgan SJ, Stromberg PC, Storts RW, Sowa BA, Lay JC. Histology and morphometry of

Strongylus vulgaris-mediated equine mesenteric arteritis. J Comp Pathol 104:89-99, 1991