CASE 3: AB968/9 (JPC 4121062-00)

Signalment:

1-month old, male, German Shepherd, Canis lupus familiaris, dog.

History:

This animal belongs to a litter of 12 puppies. Eight of them unexpectedly died with no evident clinical signs. The owner submitted only one of them for necropsy.

Gross Pathology:

The animal was in moderate body condition and good preservation status. Oral and ocular mucosae were moderately pale and there were multifocal areas of subcutaneous edema in the thoracic and abdominal regions. Mild amount of foam was present within the trachea and major bronchi. Within the thoracic cavity, there was a mild amount of serous fluid. White-grey, irregularly shaped, multifocal to coalescing areas were present on the epicardium, most prominent in the ventricles. On cut surface, many of these foci extended and affected the myocardium. Multifocal reddish areas were present on the mucosa of esophagus, stomach, and intestine. The stomach was full of digested milk. The liver was moderately and diffusely congested.

Laboratory results:

None.

Microscopic description:

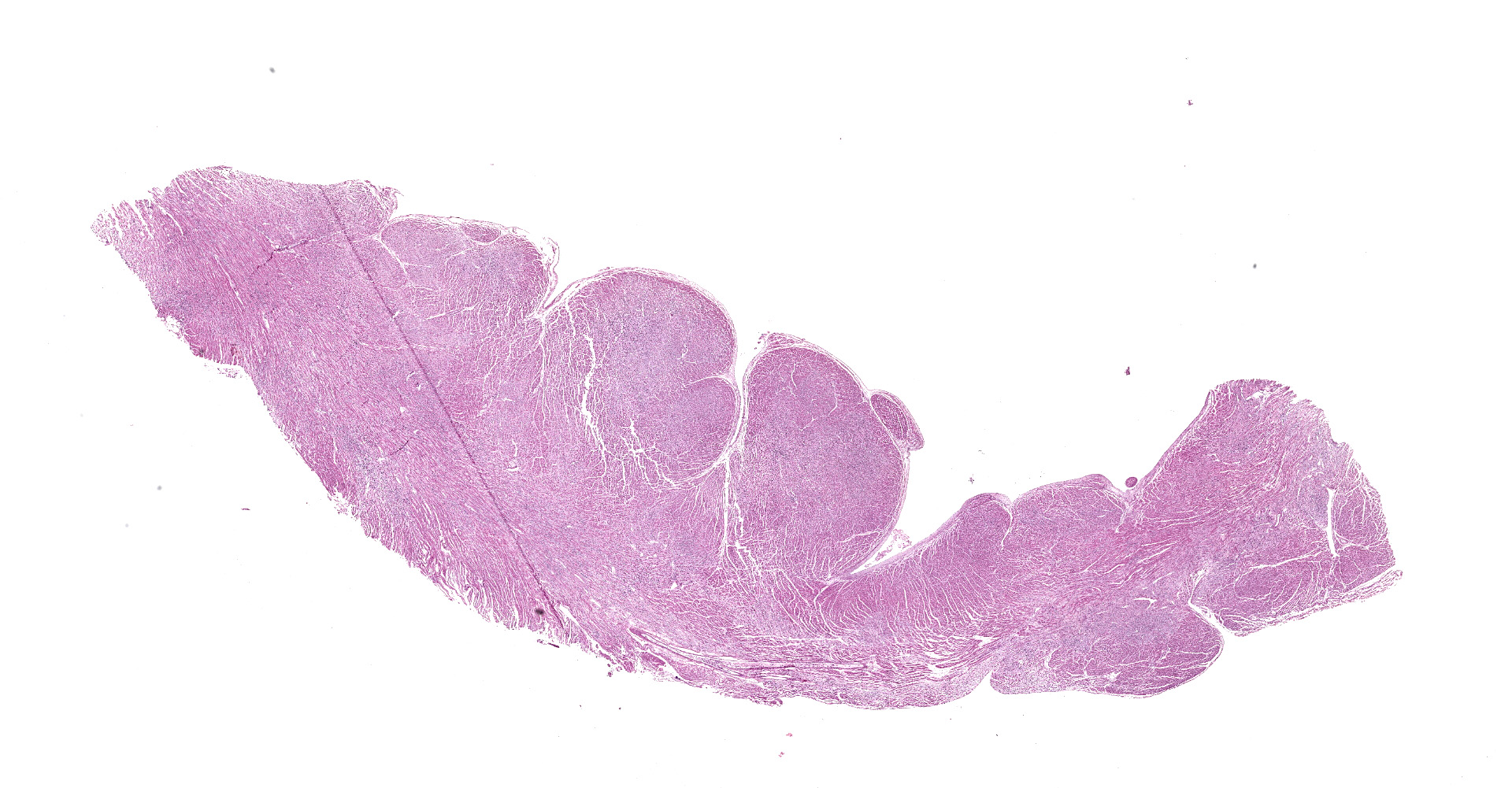

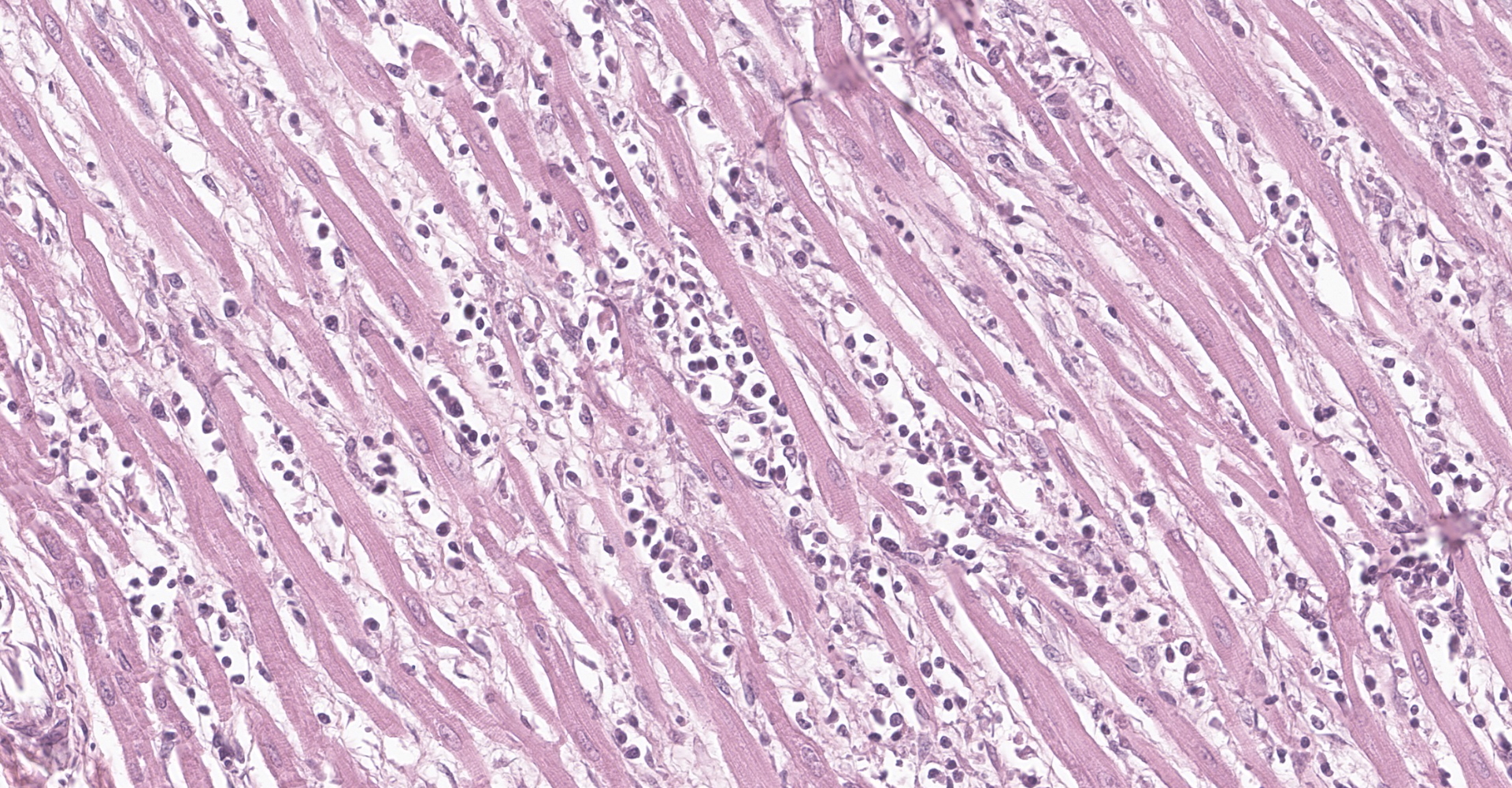

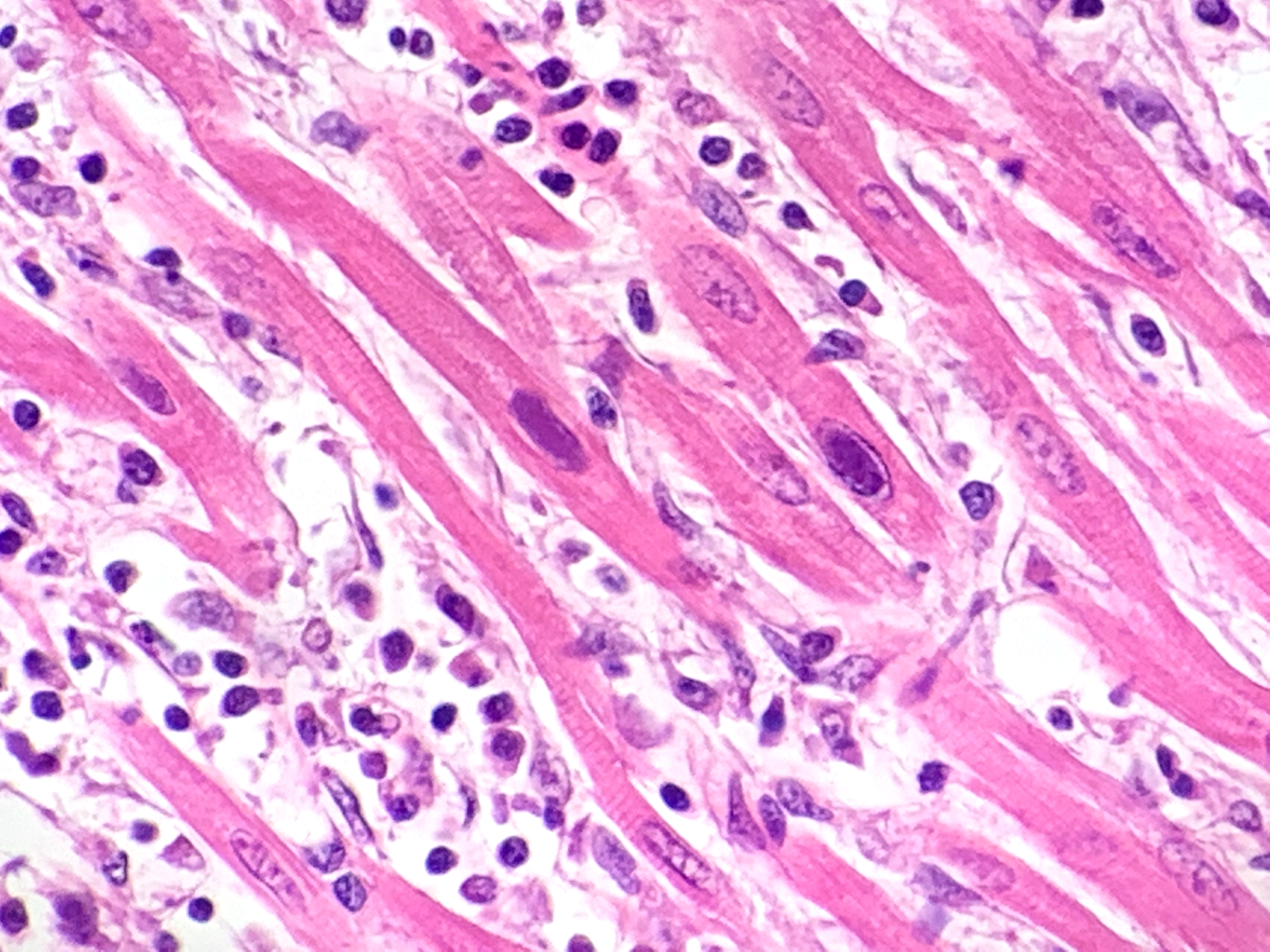

Heart: multifocal to coalescing areas of the myocardium, affecting more than 50% of the tissue, are characterized by moderate to severe fiber loss. In these areas, at transverse section, myocytes are often atrophic showing rounding ?up, irregular size (up to less than 3-4micron), and loose arrangement with peripheral large empty spaces. Occasionally they show also sarcoplasm fragmentation, rare splitting and rare sarcoplasmic vacuolation. At longitudinal section, they manifest abrupt interruption and fragmentation of sarcoplasm (disruption of microfilaments). In the affected areas, within the space between the myocytes there is moderate interstitial slightly eosinophilic and fibrillar material (loosely arranged collagen - fibrosis) with minimal amorphous mildly eosinophilic material (proteinaceous fluid, edema) associated with the presence of numerous mostly individually disseminated lymphocytes and plasma cells and rare neutrophils and macrophages. In the affected areas, frequently to occasionally (depending on the section) intranuclear amphophilic-basophilic oval sometime with blunted ends inclusion bodies entirely filling the nucleus are present within the myocytes. The lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is mildly and multifocally extending into the epicardium and endocardium.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Heart: Myocarditis, multifocal to coalescing, lymphoplasmacytic, moderate to severe, with fiber loss, fibrosis and edema, and with intramyocytes intranuclear amphophilic-basophilic viral inclusion bodies (Parvovirus spp.), Canis lupus familiaris, dog.

Contributor's comment:

Canine myocarditis is associated with disastrous effects that lead the animal either to death or to permanent cardiac damage.9 Typically, lymphoplasmacytic myocarditis is a lesion of viral infections.10 Canine parvovirus (CPV) is a well-known cause of myocarditis in young puppies.5 CPV is a member of the Parvoviridae family, whose viruses are small (23-26 nm in diameter), non-enveloped, and icosahedral with linear single-stranded DNA, that infect rapidly dividing cells, such as hematopoietic precursors in bone marrow and the gastrointestinal crypt cells.2 Parvovirus-1 (CPV-1), the first subtype of Parvovirus affecting dogs, was identified in 1967 as a cause of gastrointestinal and respiratory tract diseases in dogs.1 A few years later, in 1978, a new strain of this virus, Parvovirus-2 (CPV-2), was discovered. After infection through fecal-oral route, the virus replicates primarily in the lymphoid tissue of the oropharynx.9 The virus spreads hematogenously to infect epithelial cells present in the gastrointestinal crypts, 3-to-4 days after infection.5 This tropism is called radiomimetic.10 Because the villous basement membrane is exposed, villous fusion occurs, resulting in lack of scaffold for enterocytes replacement once the crypts recover. As a result, ulceration, permanent atrophy and, in severe cases, necrosis of the crypt epithelial cells cause an effusive and malabsorptive diarrhea that leads to severe dehydration and often death.9

A less common consequence of parvoviral infection in dogs is myocarditis often associated with necrosis of myocytes. The myocardial cells are susceptible in puppies until 15 days of age, when they stop dividing.5 A peracute and acute forms of myocarditis are described. The peracute form affects puppies at 3 to 8 weeks of age or, in case of in utero infection, even younger with sudden death a few days after parturition. The acute form typically develops in puppies ³ 8 weeks of age and causes severe dyspnea, signs of depression, eventually leading the animal to death. For both forms, myocarditis is associated with necrosis of myocytes. In the peracute form, sudden death is caused by severe necrosis, whereas in the acute form the affected areas are replaced by fibrosis. In the latter case, death is caused by the severe damage. As a result of both forms, circulatory changes affect lungs and liver causing edema and congestion.5,6 Unfortunately, no treatments are available, and prognosis is poor.9

Macroscopically, mottled pale patches and bands in the left ventricular wall are evident. If the dogs have also the enteric signs, other findings include hemorrhagic enteritis of the small intestine, enlargement of enteric lymph nodes, and reddening of Peyer patches.6 Microscopically, lymphoplasmacytic myocarditis often associated with necrosis and subsequent fibrosis, with amphophilic-basophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies are the most characteristic findings of this disease. Macrophages and fibroblasts might be present within the interstitium.6

The most effective way to control Parvovirus infection is vaccination and environmental control. Proper vaccination of female dogs prior to parturition provides passive immunity to puppies through transfer of maternal antibodies.9

Contributing Institution:

Dept. of Comparative Biomedicine and Food Science (BCA)

Veterinary Medicine ? University of Padua

AGRIPOLIS ? Viale dell'Università, 16

35020 Legnaro (PD) ? Italy

JPC diagnosis:

Heart: Myocarditis, lymphohistiocytic, diffuse, marked, with cardiomyocyte necrosis, loss, and atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and cardiomyocyte intranuclear inclusion bodies.

JPC comment:

The contributor provides a succinct summary of canine parvoviral myocarditis. A number of other viruses, in addition to other causes, are implicated in myocarditis in domestic species, including canine distemper virus, canine herpesvirus, and pseudorabies, porcine circovirus 2, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus, encephalomyocarditis virus, West Nile Virus, and the novel Bungowannah pestivirus.7 In humans, enteroviruses, including coxsackievirus, parvovirus B-19, and human herpesvirus 6 are frequent causes of myocarditis.3

The parvovirus genome encodes a major nonstructural protein 1 (NS1), and two structural proteins, VP1 and VP2. NS1 is responsible for most steps of viral replication, while the VP2 protein is the primary component of the viral capsid. VP1 is similar to VP2 but differs by having an additional 226 amino acids at its amino terminal end.4

Viral myocarditis has received additional attention recently, as there have been numerous reports of COVID-19 associated myocarditis in humans and has even been recognized as the cause of death in some patients. The lesions of COVID-19 myocarditis are usually focal, but some patients progress to arrhythmia, fulminant heart failure, and cardiogenic shock. This disease manifestation occurs as a result of both direct cell injury, as well as T-cell mediated cytotoxicity; both mechanisms can be exacerbated by an associated cytokine storm. IL-6 is currently identified as the key mediator of the cytokine storm, which mediates the pro-inflammatory responses from immune cells.8

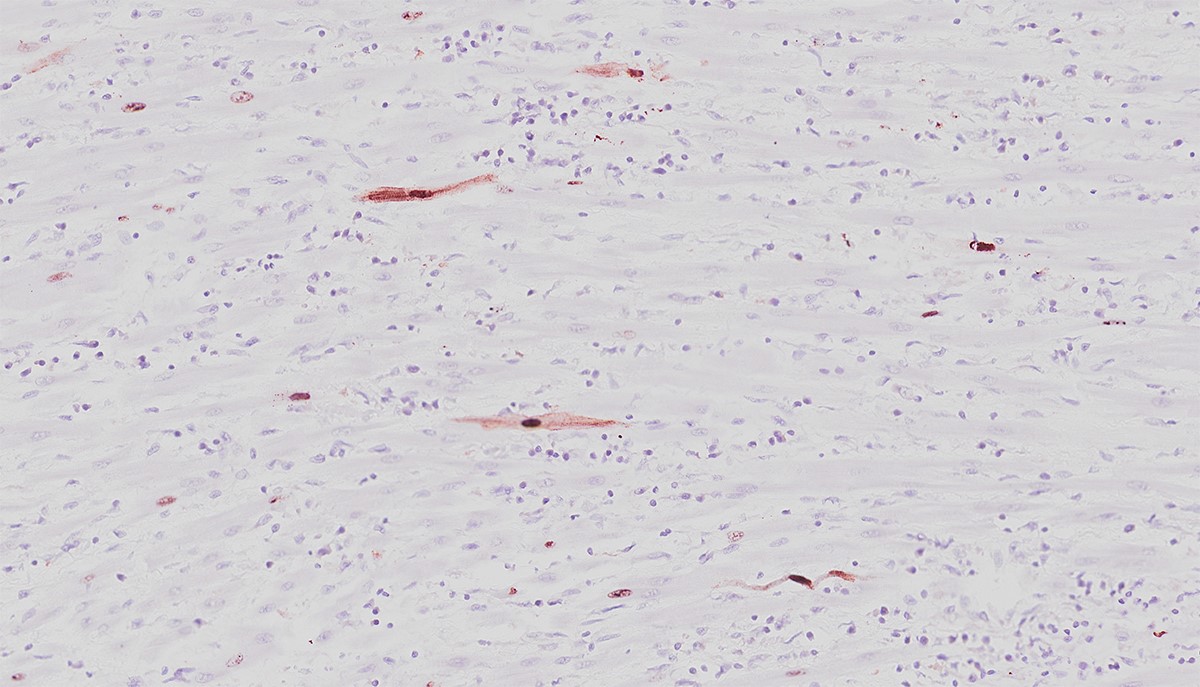

The moderator was able to demonstrate cardiomyocytes with and without intranuclear inclusions were positive for anti-CPV2 antibodies.

References:

- Binn LN, Lazar EC, Eddy GA, et al. Recovery and characterization of a minute virus of canines. Infect Immun 1970;1:503-8.

- Ford J, McEndaffer L, Renshaw R, Molesan A, Kelly K. Parvovirus infection is associated with myocarditis and myocardial fibrosis in young dogs. Vet Pathol. 2017;54(6):964-71.

3. Kang M, An J. Viral Myocarditis. [Updated 2020 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459259/

4. Landry ML. Parvovirus B19. Microbiol Spectrum. 2016;4(3): DMIH2-0008-2015. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.DMIH2-0008-2015

- Parrish CR, Have P, Foreyt WJ, et al., The global spread and replacement of canine parvovirus strain. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:1111-6.

- Robinson WF, Huxtable CR, Pass DA. Canine parvoviral myocarditis: a morphologic description of the natural disease. Vet Pathol. 1980;17:282-93.

- Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, 6th Ed, Vol 3. St. Louis, MO:Elsevier. 2016:42-43.

- Siripanthong B, Nazarian S, Muser D, et al. Recognizing COVID-19-related myocarditis: The possible pathophysiology and proposed guideline for diagnosis and management. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):1463-1471.

- Strom LM, Reis JL, Brown CC. Pathology in practice. Parvoviral myocarditis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2015; 246(8):853-5.

- Zachary JF. Cardiovascular System and Lymphatic Vessels in: Pathologic Bases of Veterinary Disease. Sixth Edition. Elsevier: St. Louis, Missouri, USA. 2017:609.