Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 2, Case 3

Signalment:

Cat (Felis vulgaris) – 5 months – female castrated

History:

Presented with clinical complaints of vomiting and lethargy. Huge amount of fluid in peritoneal cavity (ascites). No abnormalities found on echocardiac examination and blood examination. Laparascopy performed: suspicion of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Died at night.

Gross Pathology:

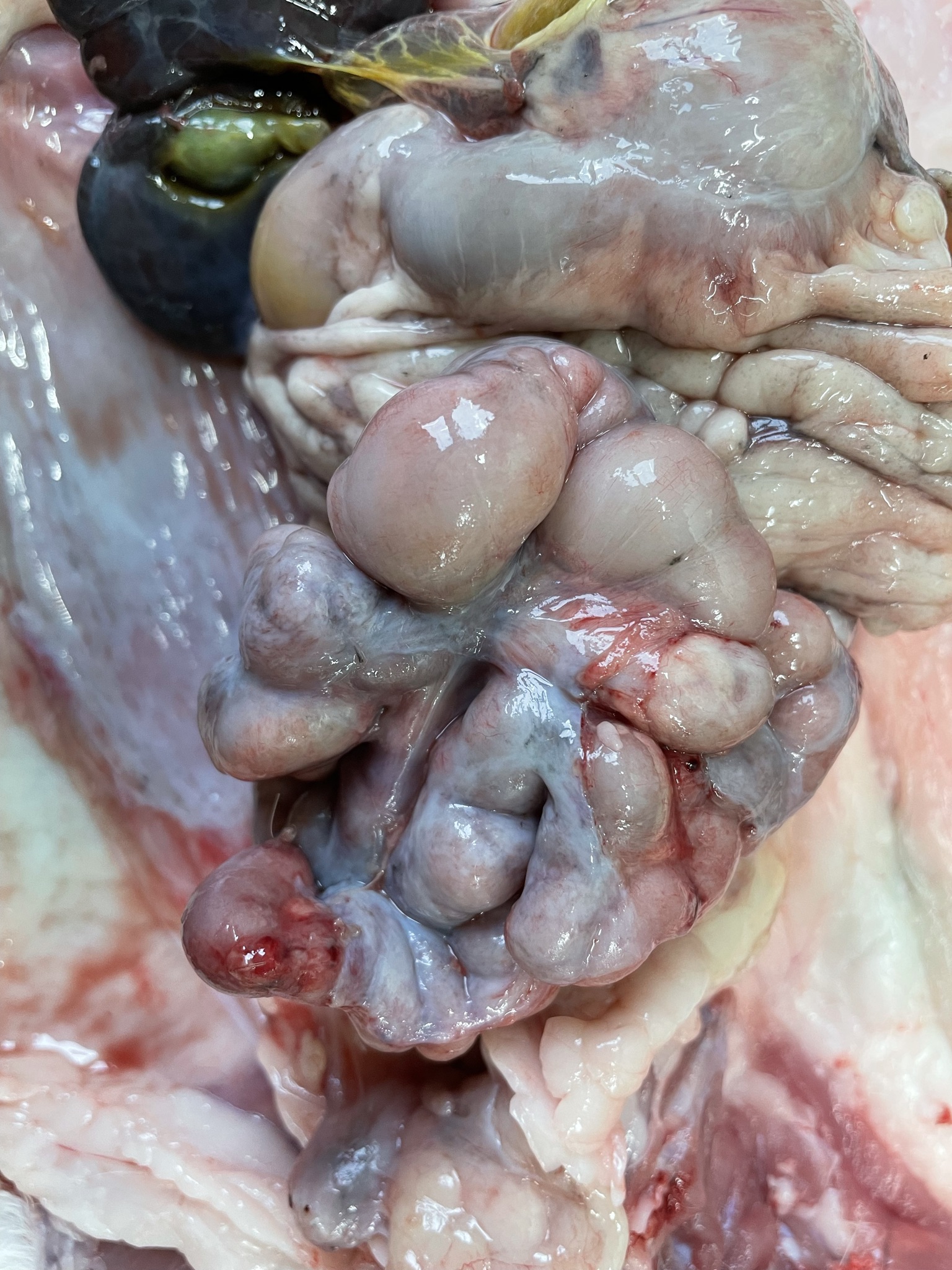

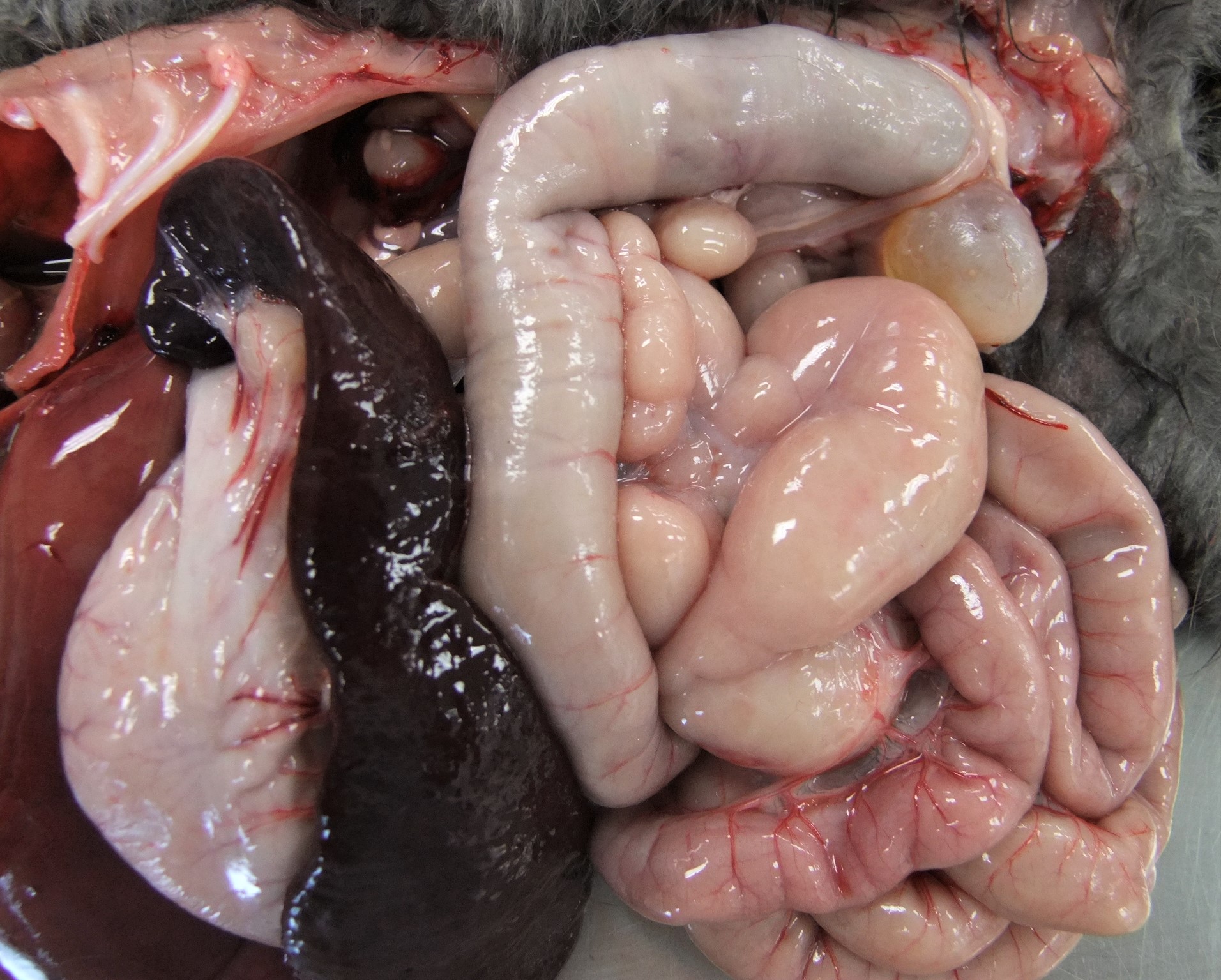

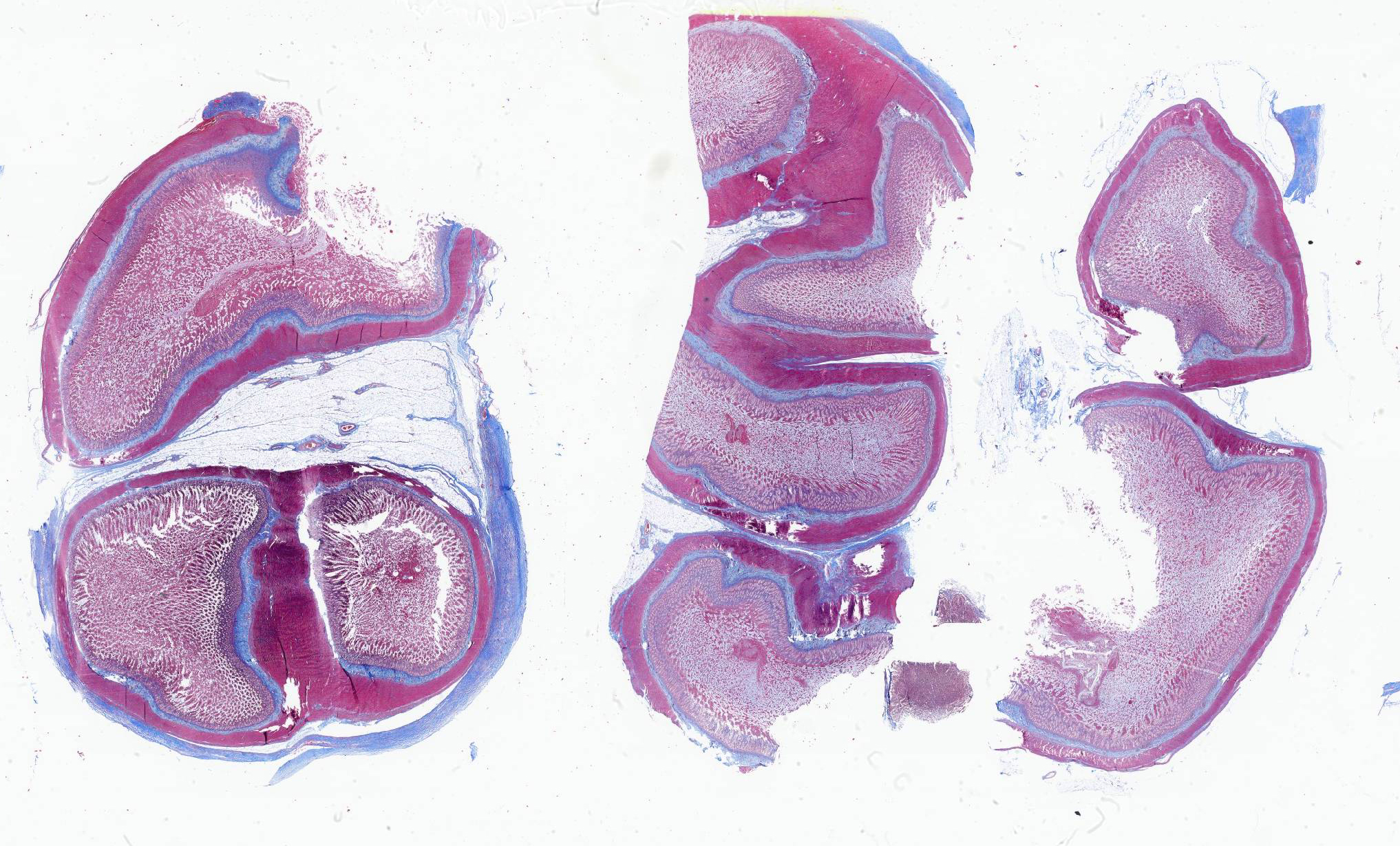

Most peritoneal organs show an abnormal morphology and are surrounded by a thick, glistening, white layer of peritoneum (figure 1 peritoneal organs in situ and figure 2 peritoneal organs removed from body).

- Small intestines are severely attached to each other. Duodenum shows a normal wall thickness but is moderately dilated. Jejunum shows a very tortuous appearance (figures 3 and 4), with a diffusely moderately to severely thickened intestinal wall and a moderate amount of yellow, granular content. The rest of the small intestine does not contain any content.

- Large intestine proximally shows the same appearance as the jejunum, more distally it has a normal appearance and contains a moderate amount of normally formed brown feces. Mucosa of all the intestinal segments is normal. There is no obvious mesentery visible.

- Liver is small with ventrally enlarged rounded edges (figure 5). It has a diffuse dark red black color with multifocal sharply delineated linear grey strikes (fibrosis, figure 6).

- Spleen is severely shrunken with absence of the normal architecture (figure 7). It is surrounded by a thick layer of connective tissue and fat (figure 8).

Laboratory Results:

Blood examination normal.

Microscopic Description:

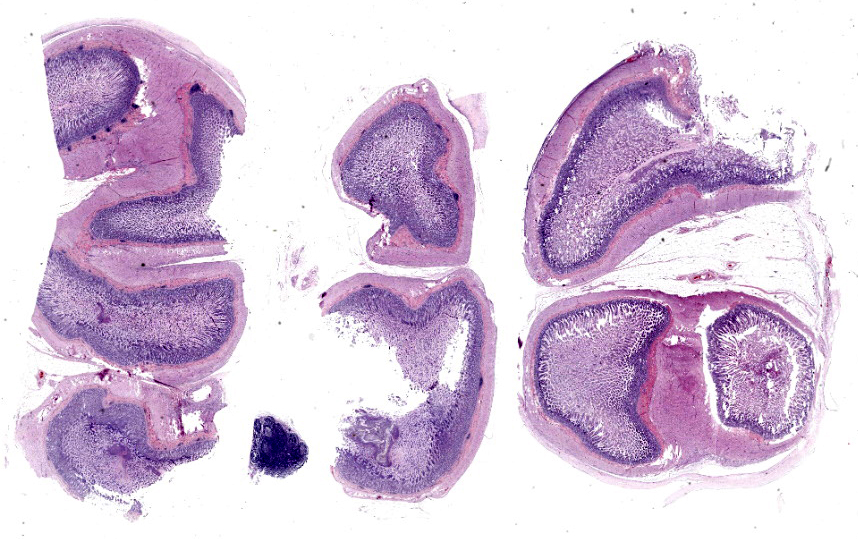

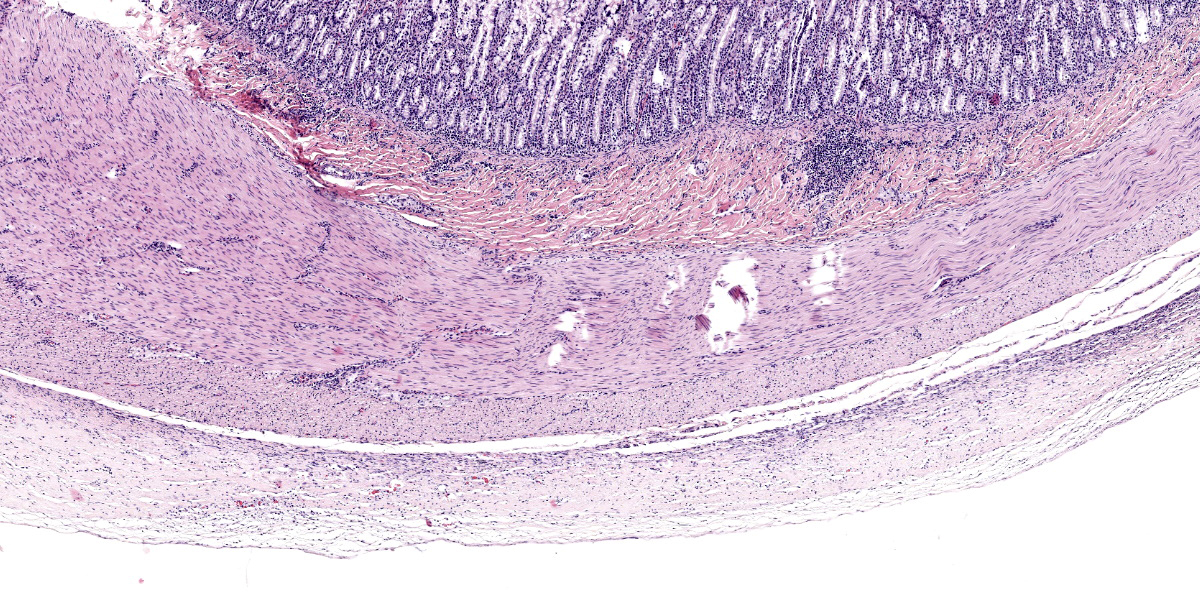

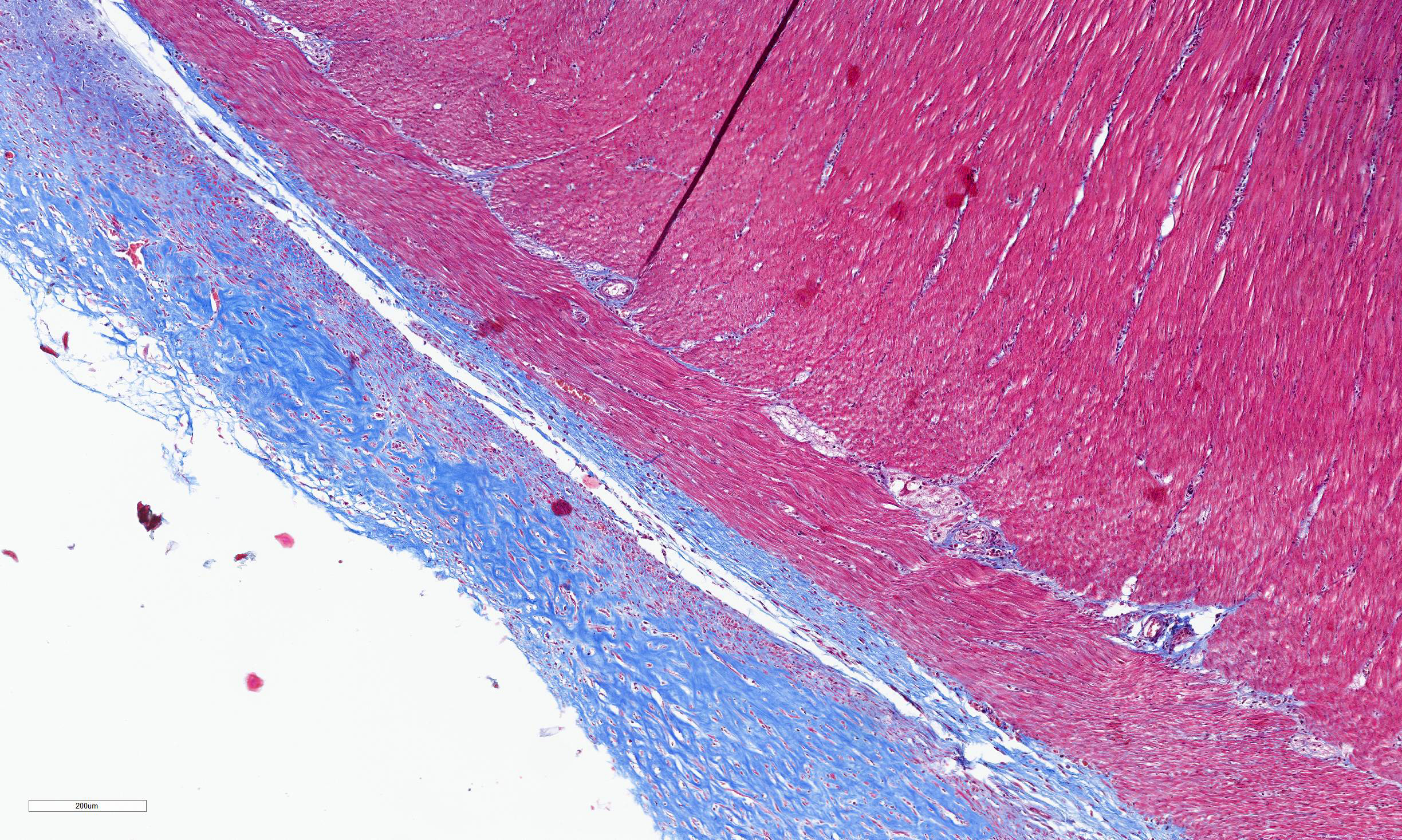

Transections of multiple intestinal segments are present. All intestines are clustered together and surrounded by a diffusely severely thickened peritoneal layer, on top of their normal thin peritoneum. The thickened peritoneal layer contains large amounts of linearly arranged collagen fibers. The connective tissue differs in maturity dependent on the location. Multifocal areas have a more mature appearance with accumulation of amorphous eosinophilic material, interspersed with small amounts of spindloid fibroblasts and densely packed connective tissue fibers, while other areas have a less mature appearance with a higher cellularity of more plump fibroblasts, a loose collagenous stroma, and moderate amounts of small tortuous blood vessels lined by plump endothelial cells (granulation tissue). Multifocal there are areas with diffuse linear translucency between the connective tissue fibers (edema). The inner part of the peritoneum shows multifocal mild mixed inflammation, mainly containing neutrophils and lymphocytes, and a mild to moderate amount of small tortuous blood vessels with plump endothelial cells. Mild to moderate lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is also seen in the tunica muscularis, tunica submucosa and the lamina propria of the tunica mucosa.

Trichrome Masson stain performed: severely thickened peritoneum

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Diffuse severe chronic encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis of the intestines.

Contributor’s Comment:

Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP), also known as ‘encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis’, is a very rare disease described in humans as well as in animals. Up until 2022, it is described in only 13 canine cases10 and 2 feline cases.6,8 It is characterized by a chronic, diffuse, fibrocollagenous thickening of parietal and visceral peritoneum with secondary encapsulation of abdominal organs, mostly small intestines.1-11,13 In human medicine, it is classified into 4 different types depending on the extent of involved abdominal organs;2,4,7 type 1 involves small intestines partially, type 2 involves small intestines completely, type 3 involves small intestines and other organs, such as stomach, cecum, colon, liver and/or ovaries, and type 4 involves the entire peritoneal cavity.

Etiopathogenesis remains incompletely understood.1,2,7 SEP can be divided in primary, idiopathic forms and secondary forms, which can be caused by lots of different underlying disorders that cause chronic low-grade inflammation of the peritoneum.1,2,8 In human medicine, peritoneal dialysis is the most common one, while other possible causes are infectious peritonitis, administration of certain medications and intra-abdominal surgery.2-11,13

SEP can give a wide variety of vague symptoms in humans, such as intermittent and recurrent, moderate to severe abdominal pain, caused by intestinal obstruction and necrosis.1,2,3,7,9,11,13 This is mostly in combination with a malnourished appearance, abdominal distention, palpable abdominal mass, nausea and vomiting.4,6,7,9,11,13. Common clinical symptoms in canine cases are also vague, and can include vomiting, diarrhea, soft feces, anorexia, depression or lethargy, enlarged abdomen and abdominal pain.1,3,5,6,10 Chronic cases can show moderate to severe low body condition and low muscle score,3,5,6 combined with symptoms specific for the underlying etiology.6 Cats show similar symptoms as seen in dogs: anorexia, intermittent vomiting, rare diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal distention and sensitivity are all described.6,7

SEP in humans and animals gives a very typical gross thick collagenous encapsulation of the small intestines with secondary adhesions between the intestinal loops, giving them a very tortuous and mass-like appearance in the central abdomen.1-3,5-7,9-11,13 Depending on the type of the disease, other organs can be additionally involved, such as stomach, cecum, colon, liver or ovaries.2,7-9 In humans, an important consequence of SEP is intestinal obstruction with necrosis,1,2,4,6,13 something that is not described in dogs and cats.1,5,6 An explanation for this lies in the very active fibrinolytic system of these species. Ascites is seen typically in dogs, while it is not common in humans.1,3,5,6,10,11,13

SEP causes very characteristic histopathological lesions: visceral and parietal peritoneum have an uneven, diffusely, moderately to severely thickened appearance.1,2,5-11,13 Different layers can be seen in the thickened peritoneum of animals. The deepest layer show mature collagenous connective tissue with densely packed collagen fibers, while the more superficial layers are built up of granulation tissue, characterized by loose collagenous stroma with presence of numerous fibroblasts, mixed with abundant, small, tortuous blood vessels lined by plump endothelium (neovascularization), and a mild mucinous deposition.5,6,8,11 Both in humans and animals, mild to moderate, mostly mononuclear, inflammation can be seen in the thickened peritoneum.4-6,8-11,13

Diagnosis of SEP remains difficult due to its vague clinical symptoms, therefore in most of the cases, there is need for a combination of history, pre-existing predisposing factors, clinical symptoms and abdominal imaging before SEP will be suspected.7 For definitive diagnosis, surgery with histopathology is necessary.

Treatment is not easy, and both surgery, medicinal therapy, nutritional support and treatment of underlying disorders are used. Surgery mostly consists of adhesiolysis with ablation of the fibrous capsule and intestinal adhesions.1,2,6,9,13 It is very important to realize the dangers of these surgeries, and complicated and fatal results are not uncommon.1,2,4 Most commonly used medicines are corticosteroids, which work anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive, and tamoxifen, which has an anti-fibrotic function.3,4,7-9,11,13

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathobiology, Pharmacology and Zoological Medicine

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ghent

Salisburylaan 133, 9820 Merelbeke, Belgium

+3292647741 - Veterinaire.pathologie@ugent.be

https://www.ugent.be/di/di05/nl

JPC Diagnosis:

Visceral peritoneum, small intestine: Fibrosis, diffuse, moderate with adhesions and scant granulation tissue.

JPC Comment:

Conference 2 concludes with a case of yet another rare entity in a cat. While we suspect some readers may not know of this particular disease, we are confident that a good description of histologic features gets one pretty close (and the search engine of choice does the rest). The large bundles of immature collagen and granulation tissue that encircle the serosal tunic (figures 4-4 and 4-5) and extend between loops of intestine is bizarre yet distinct. For this case, we ran IHCs for desmin and smooth muscle actin (SMA) to delineate fibrosis from muscle as well as special stains (Masson’s trichrome, Movat’s pentachrome) to highlight tissue architecture overall. Both desmin and SMA are strongly cytoplasmically immunoreactive within the multiple (thick and thin) layers of smooth muscle that surrounds each loop of intestine, but the chromatic stains are particularly helpful for appreciating the degree of fibrosis and adhesions between adjacent loops of bowel that are not simply a function of cut of the microtome (figures 4-7 and 4-8). Granulation tissue in particular was largely immature collagen (non-polarizing) with fewer small caliber blood vessels, though this aspect may not be consistent between all cases of SEP. Dr. Williams emphasized that the submucosa of this cat, while fairly thick, was likely normal and it was easy to be fooled unless reading feline intestinal biopsies on a consistent basis.

A recent case report from Japan describes a rare successful treatment of SEP in a cat.12 In that particular case, clinical findings were somewhat similar to the ones described by the contributor, though the cat in conference was only 5 months old at the time of presentation vice being a mature adult as the cat in Japan was. As such, our case may reflect a primary idiopathic cause rather than a chronic inflammatory one. Notably, the cat from Japan also lacked ascites and was intestinally obstructed at the time of presentation. The treatment described for the Japanese cat included multiple surgical adhesiolyses along with tapering courses of prednisolone. During surgery, placement of a hyaluronate-carboxymethylcellulose membrane around the intestine was intended to prevent recurrence of adhesions. The authors reported that the cat was symptom-free over 3 years after the second surgery. Possible factors that they considered included prevention of fibrin deposition both chemically (via anti-inflammatory doses of steroids) and physically through the use of a bioresorbable barrier.12 From a general pathology perspective, this multipronged attempt to thwart conversion of fibrin to collagen by decreasing synthesis and avenues for cross-linking was successful in this case but may prove challenging in severe and/or advanced cases of SEP.

References:

- Adamama-Moraitou LL, Prassinos NN, Patsikas MN, Psychas V, Tsioli B, Rallis TS. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in a dog with leishmaniasis. JSAP. 2004;45:117-121.

- Alshomimi S, Hassan A, Faisal Z, Mohammed A, Dandan OA, Alsaid HS. Sclerosing Encapsulating Carcinomatous Peritonitis: A Case Report. Saudi J Med Med. 2021;9:63-6.

- Barnes K. Vet Med Today: What Is Your Diagnosis? JAVMA. 2015;247(1): 43-45

- Danford CJ, Lin SC, Smith MP, Wolf JL. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(28):3101-3111.

- Etchepareborde E, Heimann M, Cohen-Solal A, Hamaide A. Use of tamoxifen in a German shepherd dog with sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51:649-53.

- Hardie EM, Rottman JB, Levy JK. Sclerosing Encapsulating Peritonitis in Four Dogs and a Cat. Vet Surg. 1994;23:107-114.

- Machado NO. Sclerosing Encapsulating Peritonitis: Review. Sultan Qaboos University Med J. 2016;16(2): 142–151.

- Sonck L, Chiers K, Ducatelle R, Van Brantegem L. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in a young cat. Vet Rec Case Rep. 2018;6:1-4.

- Tannoury JN, Abboud BN. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: Abdominal cocoon. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;18(17):1999-2004.

- Tsukada Y, Park YT, Mitsui I, Murakami M, Tsukamoto A. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in a dog with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. BMC Veterinary Research. 2022;18:383-391.

- Veiga-Parga T, Hecht S, Craig L. Imaging Diagnosis: Sclerosis encapsulating peritonitis in a dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2015;56(6):65–69.

- Yokoyama N, Kinoshita R, Ohta H, Okada K, Shimbo G, Sasaoka K, Nagata N, et al. Successful treatment of sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in a cat using bioresorbable hyaluronate-carboxymethylcellulose membrane after surgical adhesiolysis and long-term prednisolone. JFMS Open Rep. 2023 Nov 24;9(2):20551169231209917.

- Zhang Z, Zhang M, Li L. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: three case reports and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(8):1-6.