Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 9

23 October 2019

Frederic Hoerr, DVM, MS, PhD

Veterinary Diagnostic Pathology, LLC

638 South Fort

Valley Road

Fort Valley, Virginia, 22652 USA

CASE III: 2018A (JPC 4135750).

Signalment: 9-month-old, Ancona hen, Gallus gallus domesticus

History: One hen in a flock of 12 was euthanized following a 7-days history of ataxia progressing to unilateral paresis.

Gross Pathology: The bone marrow, spleen and kidney were pale. The thymus was atrophied. The liver was enlarged.

Laboratory results: None performed.

Microscopic Description:

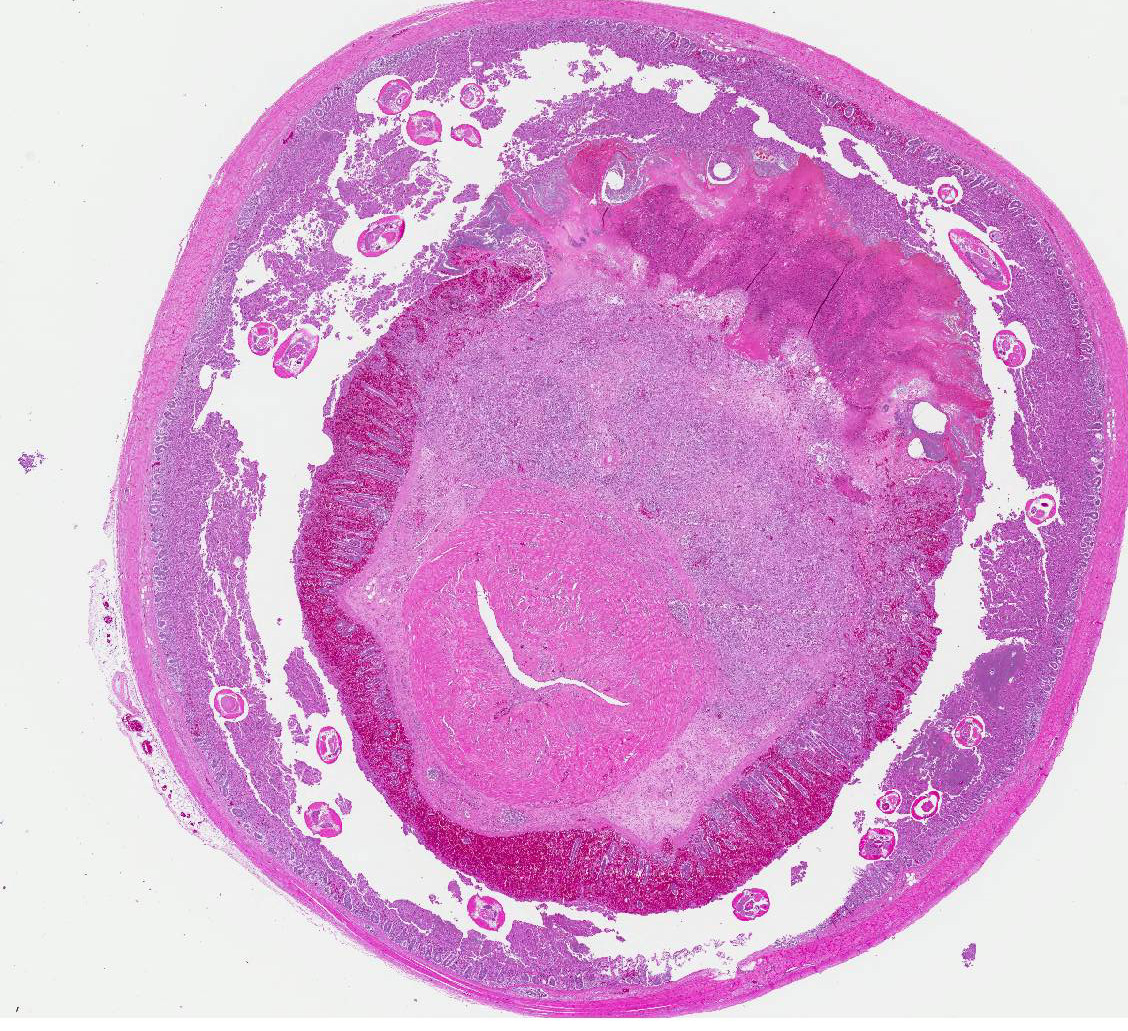

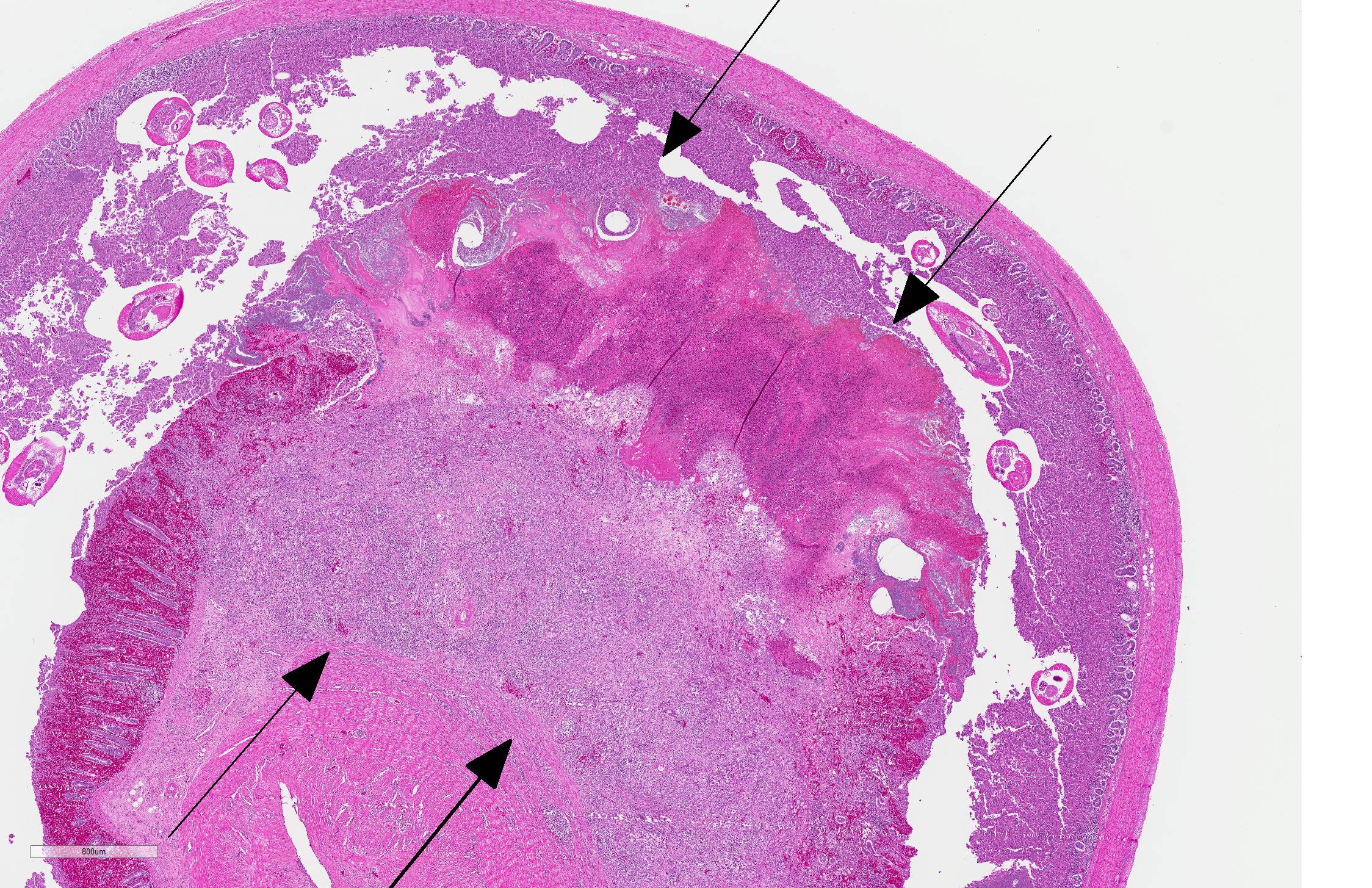

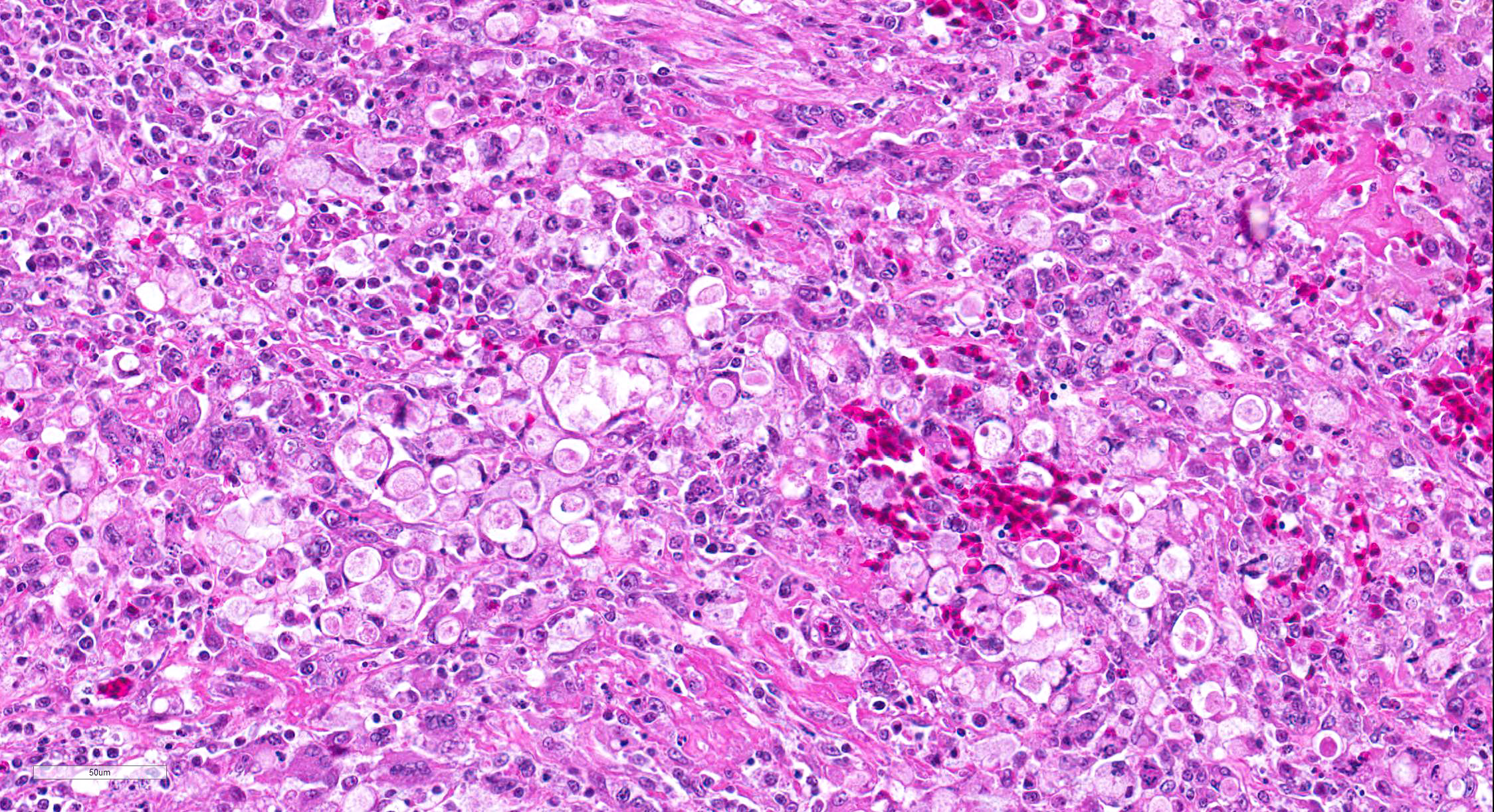

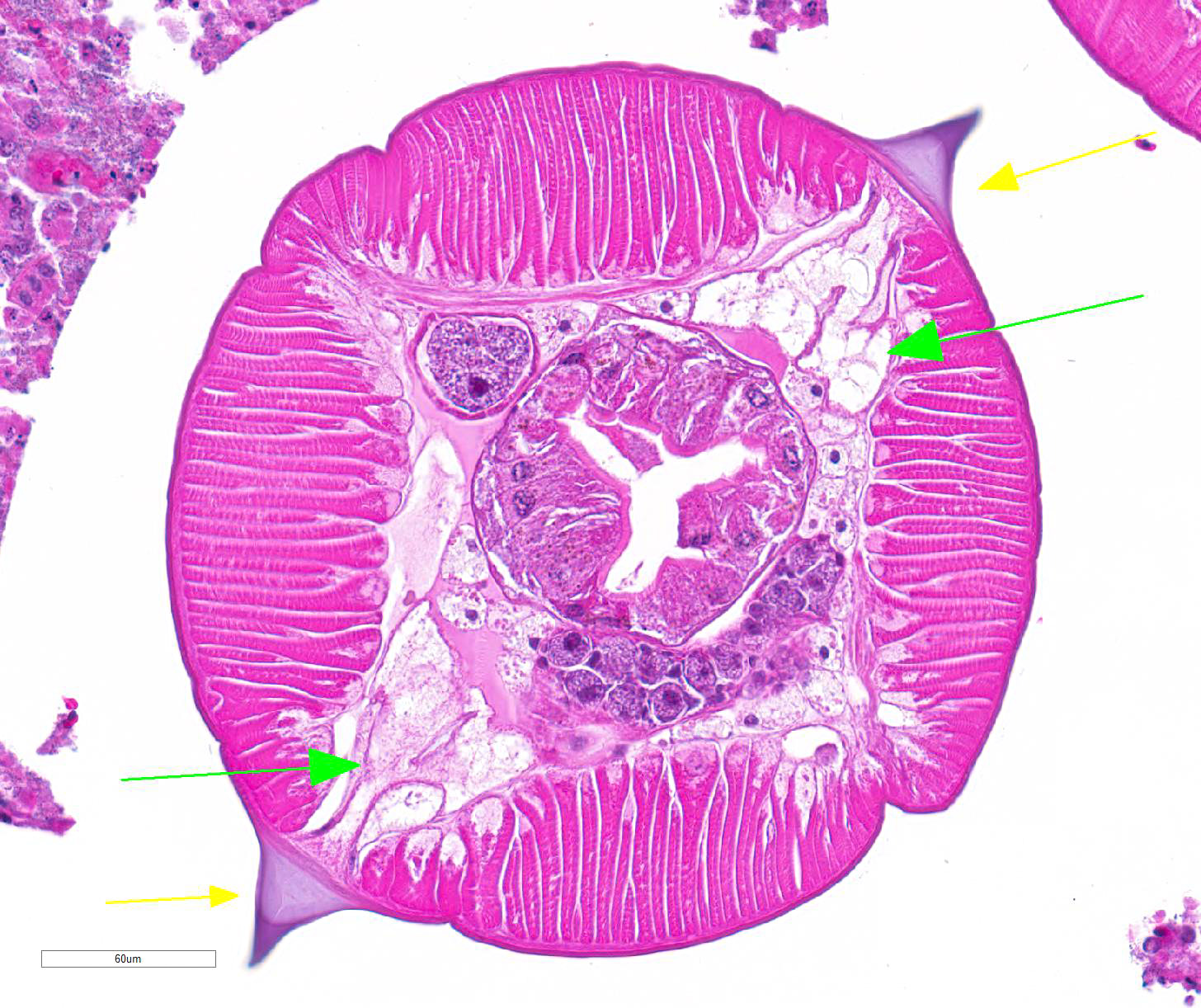

At the level of the grossly identified cecal intussusception, the mucosa and submucosa of the intussusceptum are segmentally disrupted by lytic necrosis and granulomatous inflammation. In the areas of necrosis, the mucosa is replaced by a large aggregate of cellular and nuclear debris, fibrin, myriad mixed bacteria, hemorrhage and several weakly eosinophilic protozoal trophozoites (histomonads). Trophozoites are round, 7-17 µm diameter, with a single, central, 3 µm diameter nucleus. The underlying lamina propria and submucosa are expanded by abundant macrophages, multinucleated giant cells (foreign body and Langhans-type), lymphocytes, plasma cells, few heterophils, plump fibroblasts (fibrosis), tortuous capillaries (neovascularization), and extracellular and intrahistiocytic trophozoites. The remaining mucosa of the intussusceptum is diffusely expanded by hemorrhage and superficial enterocytes are sloughed. The cecal lumen contains numerous cross and tangential sections of adult, female nematodes and few nematode eggs. The adult nematodes have a thin smooth cuticle, lateral alae, lateral cords, coelomyarian musculature, and a psuedocoelom containing a digestive tract lined by columnar cells with a brush border, a simple esophagus, an ovary, a muscular vagina and a uterus containing ova in various stages of development and few sperm. Intraluminal nematode eggs are oval and ~40 x 60 µm, with a thick smooth shell surrounding a uninucleate zygote. The mucosa of the intussuscipiens is multifocally attenuated, disrupted by autolysis, and the lamina propria is infiltrated by moderate to abundant lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Other findings: Lymphocytic meningitis and peripheral neuritis, consistent with Marekâs disease.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cecal intussusception and typhlitis, granulomatous and necrotizing, segmental, subacute to chronic, severe, with adult nematodes (consistent with Heterakis gallinarum) and protozoal trophozoites (consistent with Histomonas meleagridis)

Contributor Comment: Blackhead disease (histomoniasis) is caused by the protozoan flagellate Histomonas meleagridis. Classically this parasite is transmitted when susceptible species (i.e. gallinaceous birds, ducks, geese, game birds, and zoo birds) ingest H. meleagridis-infected ova or adults of the intermediate host, Heterakis gallinarum (cecal worm of poultry). In addition to this mode of transmission, turkeys can acquire infection through cloacal contact with contaminated feces and retrograde transport of histomonads to the ceca; a process known as cloacal drinking.2 Once in the ceca, H. meleagridis can invade the cecal mucosa and cause local inflammation and necrosis, as seen in this case. However, lesions only develop if the ceca are co-colonized by certain types of bacteria (e.g. E. coli, Clostridium perfringens, Bacillus subtilis, Salmonella sp.). The importance of bacteria in the pathogenesis of histomoniasis has been demonstrated in studies showing that H. meleagridis is avirulent in germ-free ceca6 and gnotobiotic turkeys.1 In some birds, histomonads subsequently invade the portal circulation and spreads to the liver to cause necrotizing and fatal hepatitis. This was not observed in the present case and the clinical signs that led to euthanasia were attributed to concurrent Marekâs disease.

Turkeys are highly susceptible to developing systemic histomoniasis, with mortality rates reaching 100% in some flocks.8 Conversely, in chickens, H. meleagridis causes relatively low mortality (10-20%) and high to low morbidity characterized by decreased egg production, and decreased weight gain.1,8 This difference in susceptibility is not fully understood, but current data indicate that innate and adaptive immune responses play an important role.9 In chickens, histomonads elicit an innate immune response (i.e. increased expression of IL-1β, CXCLi2, and IL-6) in the cecal tonsils within the first 24 hours of infection.10 Turkeys, however, do not upregulate these pro-inflammatory cytokines until the organism is detectable in the liver.10 In addition, one study of the adaptive immune response demonstrated that chickens have a higher percentage of IFN-ɣ mRNA expressing cells in the cecum prior to infection, suggesting these cells may play a protective role in histomoniasis.7 In contrast, the number of IFN-ɣ positive cells in the ceca of unvaccinated turkeys initially decrease following infection and then increase coincident with cecal inflammation and necrosis. It is thought that the intensity of these delayed immune responses is an important contributor to the severity of disease in turkeys.7,10

Management of histomoniasis in commercial and backyard flocks has become more difficult in recent years because the last drug approved for the prevention of blackhead disease was disallowed in the U.S. in 2016.1 Several alternative therapies are currently being investigated, but none have been proven to be sufficiently efficacious for broad application and a protective vaccine is not available.1 Therefore, traditional environmental management practices (e.g. biosecurity, management of soil and litter, avoid comingling highly susceptible species with chickens, etc.) are of increasing importance in the prevention of this disease.

Contributing Institution:

Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (WADDL); Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology, Washington State University. https://waddl.vetmed.wsu.edu/ https://vmp.vetmed.wsu.edu/

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Cecum: Intussuception.

2. Cecum: Typhlitis, necrohemorrhagic and granulomatous, transmural,

multifocal to coalescing, marked with numerous amebic trophozoites.

3. Cecum, lumen: Adult ascarids, multiple.

JPC Comment: With the recent removal of nitarsone, the last remaining feed additive targeting flagellates, the economic importance of Histomonas meleagridis is greater than ever before. A recent retrospective of the disease in commercial turkeys was published in 20184, in concert with similar retrospective studies in France and Germany. In the California study, most cases occurred in warmer months from April to October, likely due to the longer survival of trophozoites outside the host during these months. Affected birds ranged from 2 weeks to 15 months; and the disease is less frequent, but no less severe in older birds. In most autopsied birds, histomoniasis was considered the primary cause of death. Histomonads were observed outside of the cecum and liver in 12/66 cases; other affected organs included spleen kidney, bursa, proventriculus, pancreas, lung, and crop. In five out of the 66 cases, the infection spread to all houses in the facility but cecal worms were only seen in 2 out of 66 cases, suggesting other forms of spread and the possibility of more resistant forms.4

H. meleagridis has recently been characterized in peafowl.2 They may be experimentally infected with H. meleagridis, but natural infections are rare. In a recent retrospective of infected peafowl, characteristic gross and histologic lesions associated with H. meleagridis (necrotizing typhlitis and hepatitis) were noted in each case, however, no birds had concurrent H. gallinarum infection. One bird had a concurrent infection with Tetratrichomonas gallinarum; the significance of this infection in facilitating the histomonad infection (seen with a number of other bacteria as mentioned by the contributor) is yet unclear.2

Interestingly, in a retrospective of common mortality in commercial egg-laying chickens, intussusception (classified along with volvulus under "twisted intestine") ranked seventh in the top fifteen causes of normal mortality at 3.5% of 3337 necropsies. Intussusception is reported to occur frequently secondarily to coccidiosis, necrotic enteritis, or intestinal parasitism, although in that particular study, intestinal parasites were not found. Affected birds demonstrate emaciation and atrophy of the reproductive tract, suggesting that the lesions are generally chronic in nature.3 The moderator discussed the possibility of a number of cases of intussusception seen in non-parasitized birds perhaps being the result of skipping a feeding day in pullets, similar to the so-called "re-feeding syndrome" seen in humans.

References:

1. Clark S, Kimminau E. Critical Review: Future Control of Blackhead Disease (Histomoniasis) in Poultry. Avian Dis. 2017;61: 281-288.

2. Clarke LL, Beckstead BM, Hayes JR, Rissi D. Patholoic and molicular charcterization of histomoniasis in peafowl (Pavo cristatus). J Vet Diagn Investig 2017; 29(2):237-241.

3. Fulton RM. Causes of normal mortality in commercial egg-laying chickens. Avian Dis 2017; 61(3): 289-295.

4. Hauck R, Stoute S, Chin RP, Senties-Cue CG, Shivaprasad HL. Retrospective sutdy of histomoniasis (blackhead) in California turkey flocks 2000-2014.

5. Hu J, Fuller L, McDougald LR. Infection of turkeys with Histomonas meleagridis by the cloacal drop method. Avian Dis. 2004;48: 746-750.

6. Kemp RL. The failure of Histomonas meleagridis to establish in germ-free ceca in normal poults. Avian Dis. 1974;18: 452-455.

7. Kidane FA, Mitra T, Wernsdorf P, Hess M, Liebhart D. Allocation of Interferon Gamma mRNA Positive Cells in Caecum Hallmarks a Protective Trait Against Histomonosis. Front Immunol. 2018;9: 1164.

8. McDougald LR. Blackhead disease (histomoniasis) in poultry: a critical review. Avian Dis. 2005;49: 462-476.

9. Mitra T, Kidane FA, Hess M, Liebhart D. Unravelling the Immunity of Poultry Against the Extracellular Protozoan Parasite Histomonas meleagridis Is a Cornerstone for Vaccine Development: A Review. Front Immunol. 2018;9: 2518.

10. Powell FL, Rothwell L, Clarkson MJ, Kaiser P. The turkey, compared to the chicken, fails to mount an effective early immune response to Histomonas meleagridis in the gut. Parasite Immunol. 2009;31: 312-327.