Signalment:

Adult male chinchilla,

Chinchilla lanigera.The chinchilla was found dead with no reported premonitory signs. This animal was one of seven chinchillas submitted for necropsy during an approximately 3-week period that were either noted to exhibit respiratory distress and tachypnea or found dead without premonitory signs.

Gross Description:

The caudal portion of the right cranial lung lobe was firm and mottled red to tan. Small amounts of soft to gelatinous, pale tan material were adhered to the pleural surface of the affected lung lobe. All lung lobes oozed a small volume of clear fluid on section.Â

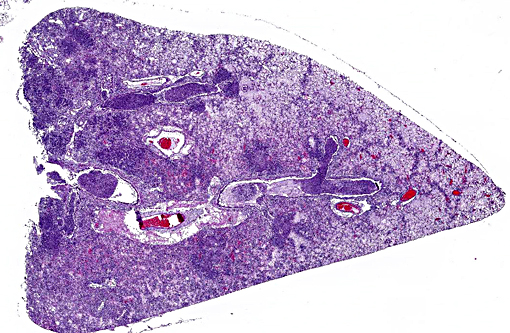

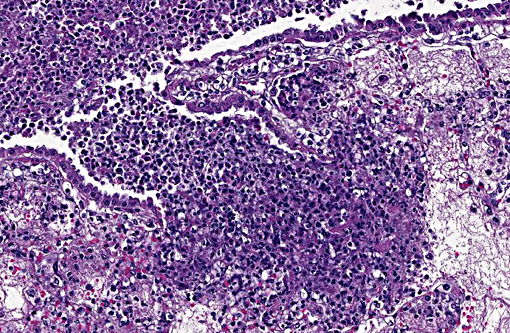

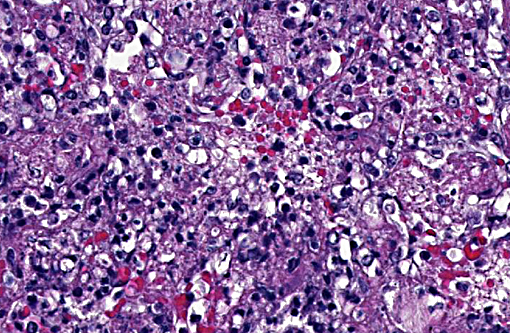

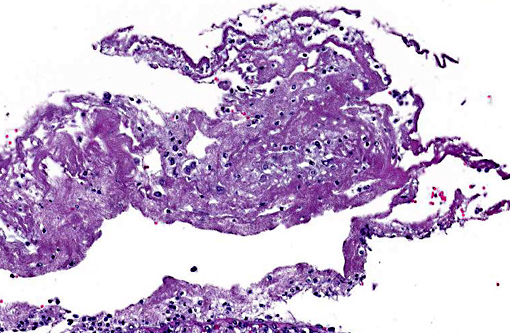

Histopathologic Description:

In the most severely affected sections, 50-75% of airways and alveolar spaces are multifocally obscured and expanded by large numbers of heterophils that are often degenerate with poorly demarcated, round to streaming nuclei (oat cells), macrophages, small numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells, aggregates of homogenous, eosinophilic material (fibrin), wispy to granular eosinophilic material (fibrin and proteinaceous fluid), and variable amounts of cellular and karyorrhectic debris (necrosis). Large numbers of small, <1 x 2 μm coccobacilli form dense intra- and extracellular colonies. Similar inflammation and necrosis also obscures and replaces alveolar septa. Bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial cells are often hypertrophic (reactive) with occasional areas of attenuation and infrequent piling of cells (hyperplasia). There are multifocal areas of acute alveolar hemorrhage and erythrophagocytosis. The adventitia surrounding pulmonary vessels and airways is often expanded by clear space with wispy, eosinophilic material and small numbers of heterophils, macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells. The alveolar spaces surrounding areas of intense inflammation contain copious amounts of wispy, eosinophilic material (edema) and moderate numbers of macrophages with foamy cytoplasm and fewer heterophils and lymphocytes. Moderate amounts of fibrin with small numbers of associated heterophils, macrophages and lymphocytes are adhered to the pleural surface multifocally; the underlying pleura is lined by plump, reactive mesothelial cells. In less severely affected sections, small to moderate numbers of heterophils infiltrate the bronchial and bronchiolar mucosa and are associated with small amounts of fibrin and edema. Alveolar septa are multifocally fragmented with the formation of large alveolar spaces (emphysema). Small numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells and heterophils mildly expand perivascular spaces.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: Bronchopneumonia, necrosuppurative, fibrinous, acute, severe with oat cells, pulmonary edema, alveolar hemorrhage, fibrinous pleuritis and intralesional, intra- and extracellular coccobacilli colonies.

Nasal cavity (tissue not submitted): Rhinitis, mucopurulent, diffuse, moderate, subacute with intralesional, intra- and extracellular coccobacilli colonies and multifocal, mild mucosal erosion and ulceration.

Lab Results:

Aerobic bacterial culture of the lung yielded the growth of many

Bordetella bronchiseptica; B. bronchiseptica was also identified in three additional chinchillas with similar gross and histologic lesions.Â

Mycoplasma culture and pneumovirus PCR were negative.

Condition:

Bordetella bronchiseptica

Contributor Comment:

Gross, histologic and ancillary findings were consistent with a diagnosis of pulmonary and upper respiratory bordetellosis.Â

Bordetella bronchiseptica was isolated from samples of lung for all chinchillas (n=4) that were submitted for aerobic bacterial culture, and all 7 chinchillas showed similar gross and histologic features. While

B. bronchiseptica can commonly be a secondary, opportunistic pathogen, as lung samples were negative for consistent growth of other significant bacteria,

Bordetella is believed to be the primary cause of disease in these chinchillas. Other significant associated findings in the affected chinchillas included rhinitis (n=3), tracheitis (n=2) and otitis media (n=1). Though not present in the submitted case, affected chinchillas with a more prolonged disease period demonstrated marked pneumocyte hyperplasia and hypertrophy; lung samples were negative for pneumovirus by quantitative PCR.

In small mammals, respiratory bordetellosis is most commonly reported in guinea pigs and rabbits; however, outbreaks in commercial chinchilla operations have been documented.(2) The contributor has also observed similar histologic changes, including the presence of prominent colonies of coccobacilli, in wild eastern gray squirrels (

Sciureus carolinensis) with pulmonary bordetellosis. Other species in which

B. bronchiseptica can be a significant pathogen include dogs (infectious tracheobronchitis), cats (tracheitis and bronchopneumonia) and pigs (atrophic rhinitis and neonatal pneumonia).

Like

Mannheimia and

Actinobacillus spp.,

Bordetella bronchiseptica encodes a pore-forming, repeat in toxin (RTX) family virulence factor, adenylate cyclase toxin (ACT). ACT is an essential virulence factor that can: i) disable innate immunoprotective functions, including phagocytosis, chemotaxis, and superoxide production, ii) modulate immune responses through alterations in cytokine secretions, and iii) trigger apoptosis in macrophages.(5) Other important virulence factors of

B. bronchiseptica include filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), dermonecrotic toxin (DNT), tracheal cytotoxin, osteotoxin, fimbriae and a Type-III secretion system.(5)

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Pleuropneumonia, necrotizing and fibrinosuppurative, acute, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with numerous bacilli.

Conference Comment:

This is a great descriptive case with an impressive abundance of fibrin within most alveolar airways and, in some sections, causing a thickening of the pleura.

Bordetella bronchiseptica has an array of virulence factors as explained by the contributor, yet in many domestic animal species it is a known commensal organism of the upper respiratory tract. Its presence is not typically equitable with clinical disease unless an immune compromising event takes place in the host.(1) Of particular importance in laboratory species is its ability to take refuge within clinically normal rabbits, and subsequently spread to and wreak havoc in guinea pigs if housed in close proximity.(4) Pulmonary lesions are typically suppurative in most species, though fibrinous exudation within alveoli has been described in acute cases.(4) Fibrinous bronchopneumonias or pleuropneumonias are the result of severe pulmonary injury and, thus cause death earlier in the sequence of the inflammatory process than suppurative pneumonias.(3) Dramatic clinical signs and death can occur even in cases involving only 30% or less of the total pulmonary surface area.(3) Although lesions in this case had areas of suppurative inflammation, fibrin predominated and this finding correlates with the rapid onset and death provided in the case history.Â

References:

1. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:638-639.

2. Lazzari AM, de Vargas AC, Dutra V, et al. Infectious agents isolated from Chinchilla laniger. Ci+�-�ncia Rural. 2001;31:337-340.

3. Lopez A. Respiratory system, mediastinum, and pleurae. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012:499-500.

4. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008:226-228, 267-268.

5. Register K, Harvill E. Bordetella. In: Gyles CL, Prescott JF, Songer G, Thoen CO, eds. Pathogenesis of Bacterial Infections in Animals. 4th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:411-427.