Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 6

October 4th, 2017

CASE IV: T17-14880 (JPC 4101090).

Signalment: Adult, peacock, Pavo cristatus, avian.

History: The bird and others in the same flock had respiratory symptoms with rapid breathing and purulent ocular discharge.

Gross Pathology: Pasty to dry exudate was present on the conjunctiva of the eyes. Upon opening the carcass, the bird was found in a fair body condition. The oropharynx was rough and crusty. The crop was empty. Liver, kidney and lungs were congested. There was no other grossly visible lesion.

Laboratory results: Oropharyngeal/tracheal tissues were positive for herpesvirus by PCR. The sequenced amplicon showed identity to Gallid herpesvirus-1.

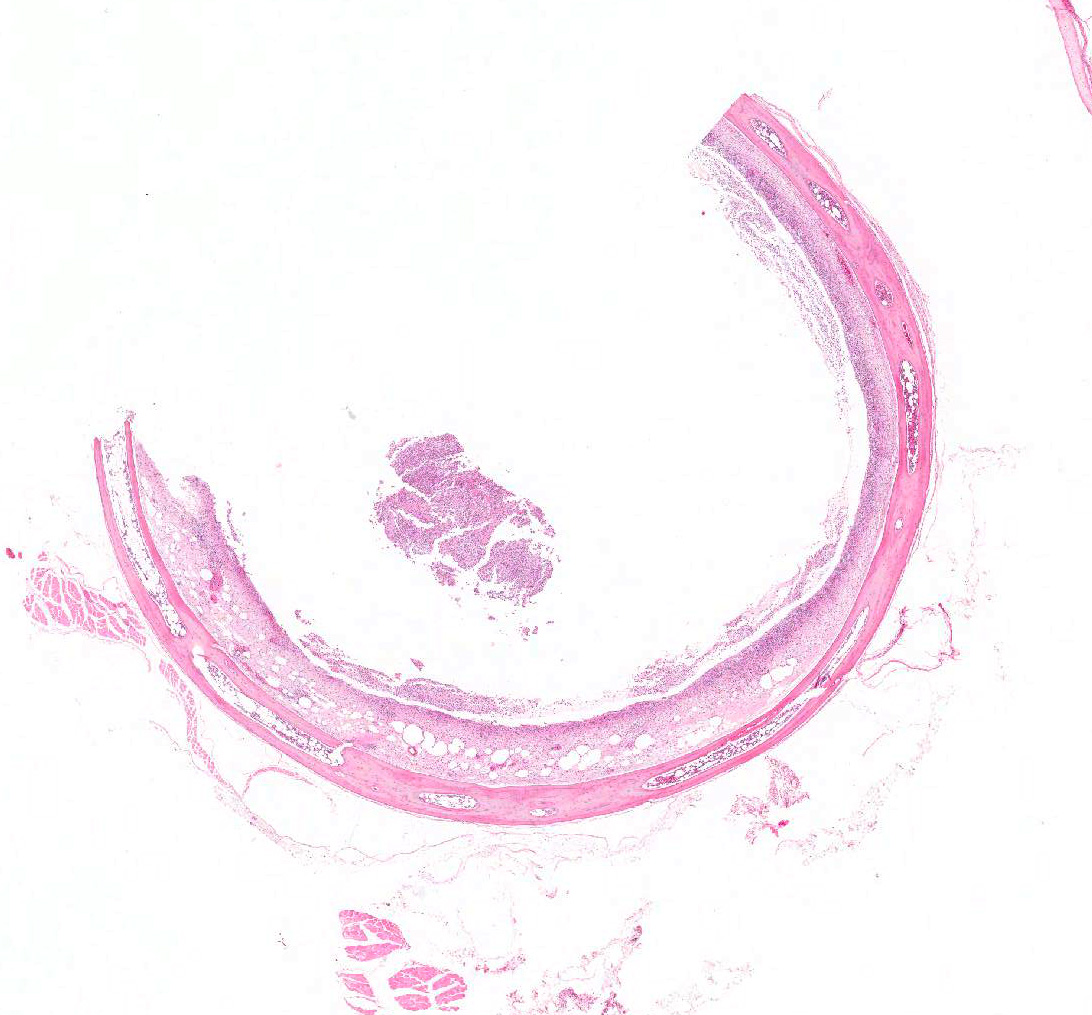

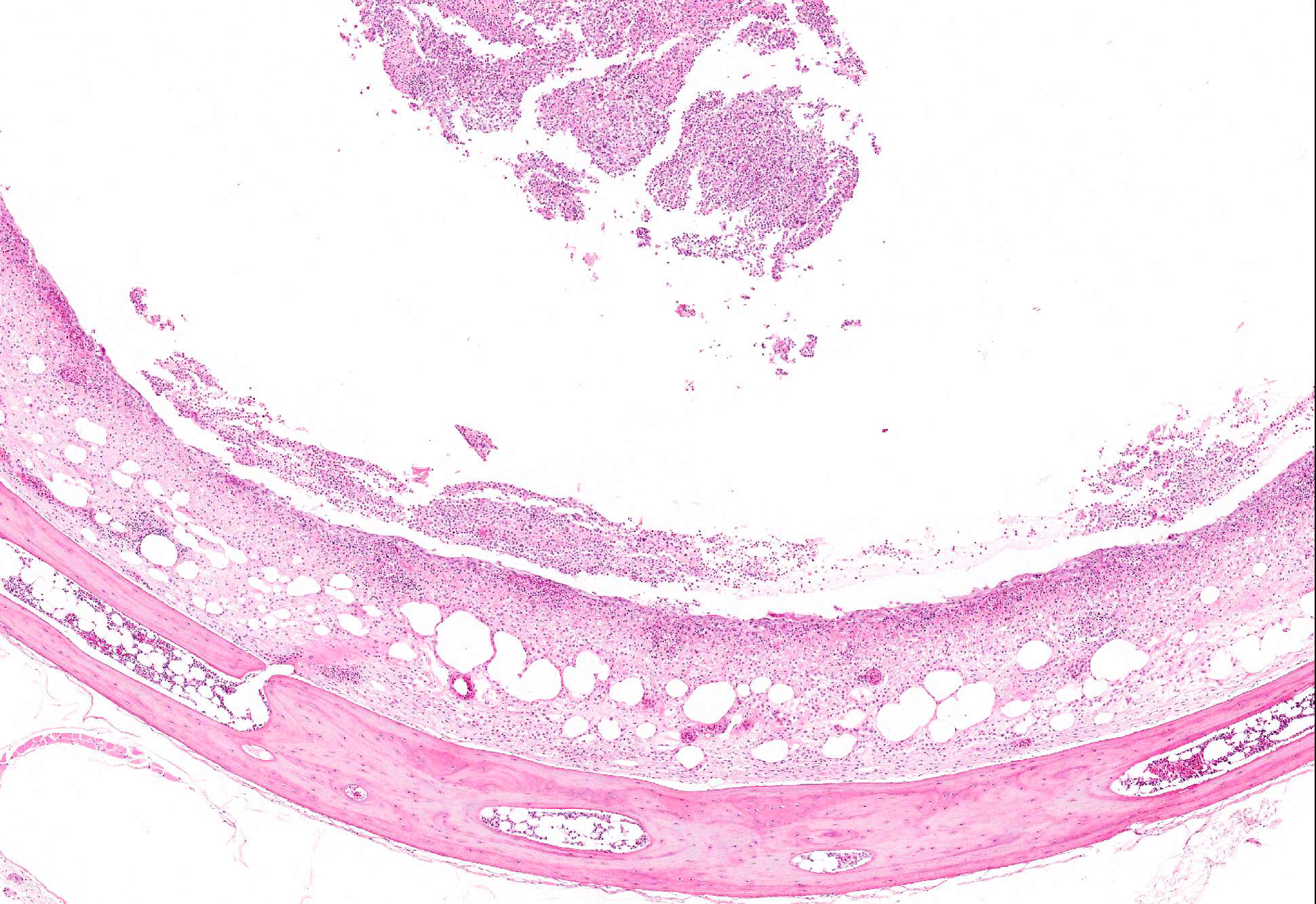

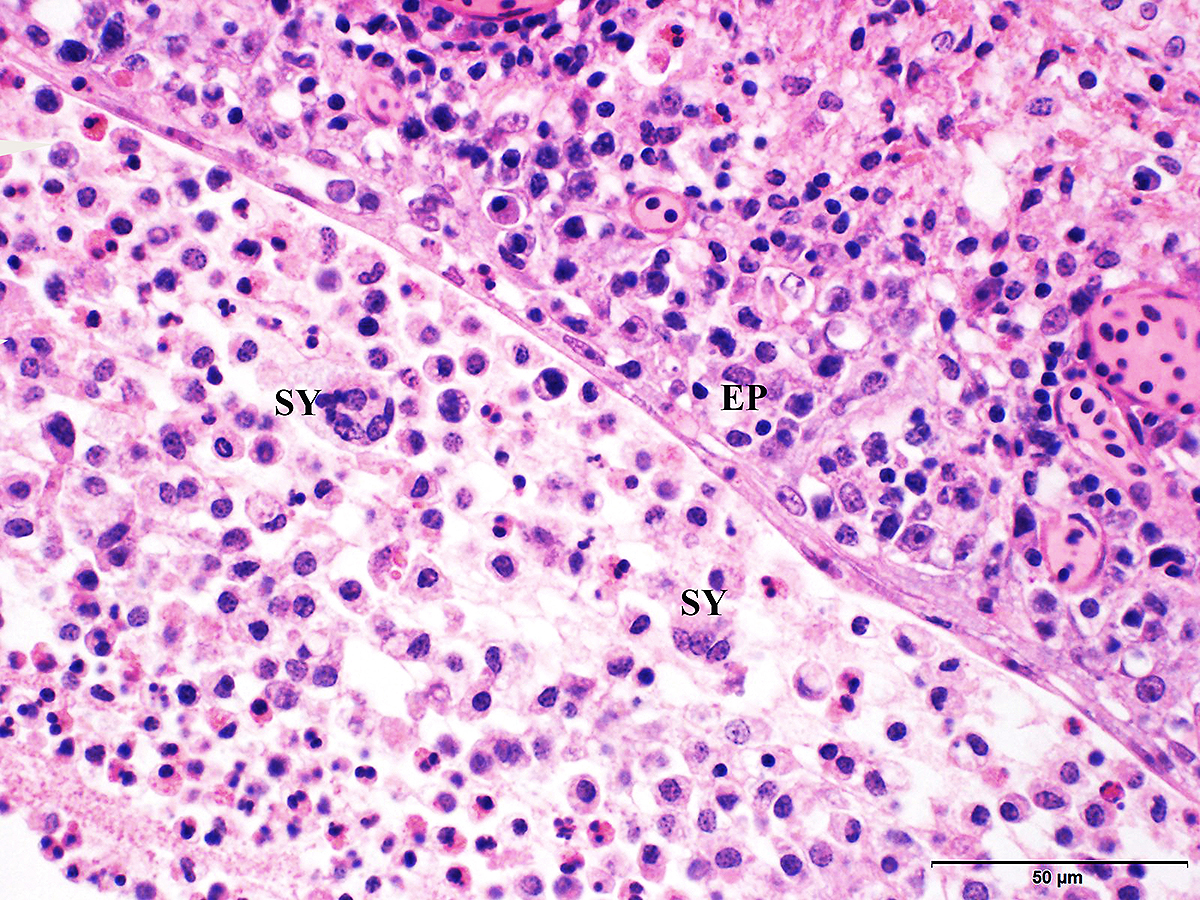

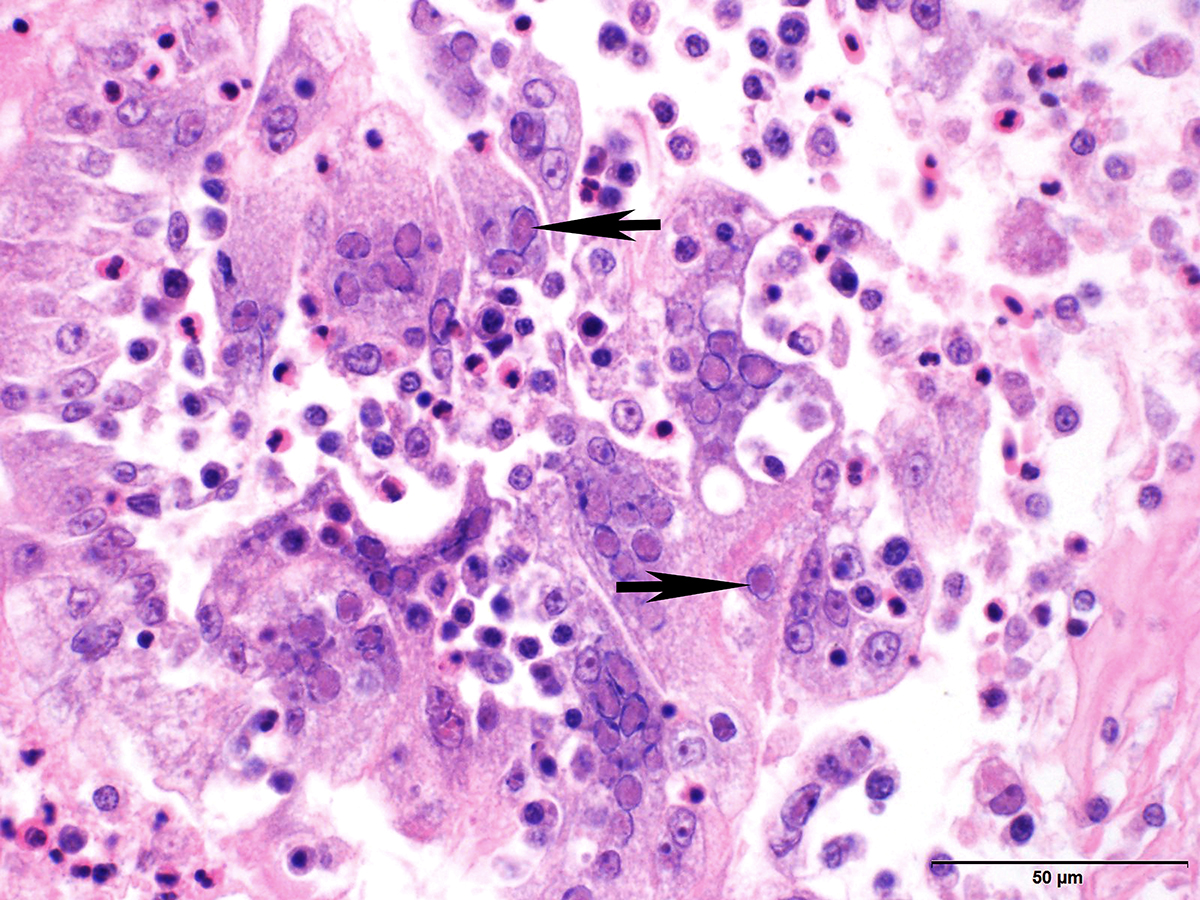

Microscopic Description: Trachea and larynx: The lesions vary from section to section. In all sections the tracheal mucosa is variably infiltrated with abundant lymphocytes, macrophages, scattered multinucleated syncytial cells and heterophils. The inflammatory cells transmigrate the epithelium and also extend to the submucosa. Scattered epithelial cells contain eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions. The laryngeal mucosa (sections not included) is ulcerated and large numbers of lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells and occasional heterophils infiltrate the submucosa. Large numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells and scattered heterophils are also observed in the submucosa of palpebral conjunctiva (sections not included). In a focally extensive area, abundant lymphocytes, macrophages and several multinucleated giant (syncytial) cells infiltrate a section of bronchus (sections not included), extend to the adjacent pulmonary parenchyma and variably fill the parabronchus and air capillaries. Scattered epithelial cells contained eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis:

Trachea and larynx: Lymphoplasmacytic and heterophilic to pyogranulomatous tracheitis and laryngitis (laryngotracheitis) with syncytial cells and intranuclear inclusion bodies.

Contributors Comment: The lesion is consistent with infectious laryngotracheitis due to gallid herpesvirus-1. Infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT) is a highly contagious respiratory disease of poultry reported in most countries around the world and causes significant economic losses in the poultry industry worldwide.1, 4, 7 ILT virus (ILTV) belongs to alphaherpesviridae and the Gallid herpesvirus-1 species.7 Different strains of the virus are recognized. In US infectious laryngotracheitis virus (ILTV) strains and field isolates were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) into nine different genotypes.5

Natural transmission of ILTV is via respiratory and ocular routes. All ages of chickens including pheasants, pheasant-bantam crosses, and peafowl are affected, but chickens older than 3 weeks are most susceptible. The sources of ILTV are clinically affected chickens, latent infected carriers, contaminated dust, litter, beetles, drinking water and fomites.7 The ILT virus can be spread by the transportation of animals, personnel, and equipment. In one study it was indicated that one of the critical points identified as a potential source of virus transmission was roads that were frequently used by the poultry industry within the outbreak area.6

Clinical signs can be severe or mild. Dyspnea and bloody mucus and high morbidity and mortality could be seen in severe forms. In the mild form depression, reduced egg production and weight gain, conjunctivitis, swelling of the infraorbital sinuses (almond shaped eyes), and nasal discharge are observed. The mild form is the most commonly seen type in the US and is called silent, vaccinal, or almond-shape eye ILT.7 Clinical cases with the history of the pump handle type of respiration, conjunctivitis, coughing up of blood and mortality up to 80% is often reported by poultry farmers and veterinarians in India.2

Gross lesions are observed in the larynx and trachea. With the severe form, the mucosa of the respiratory tract shows inflammation and necrosis with hemorrhage. A characteristic feature is intranuclear inclusion bodies in epithelial cells. Inclusion bodies are generally present for a few days at the early stage of infection before epithelial cells die. Epithelial cells also form multinucleated cells (syncytia). Laboratory diagnosis (virus isolation and DNA detection) is required to confirm ILT, and rule out other diseases such as infectious bronchitis, Newcastle disease, avian influenza, infectious coryza, and mycoplasmosis that may have similar clinical signs and lesions.

Vaccination is effective to prevent ILTV infection. However, vaccine viruses can create latent infected carrier, which could be a source for spread of virus to non-vaccinated flocks. Therefore, it is recommended that ILT vaccines be used only in endemic areas. It is important to avoid contact between vaccinated or recovered field virus infected birds with non-vaccinated chickens. It is also critical to remove contaminated fomites for prevention and control of ILTV infection. To control ILTV outbreaks, improved biosecurity and management practice are necessary.7 Previous studies have demonstrated that the most effective way to prevent or control an ILT outbreak is through enhanced biosecurity, and implementation of an appropriate vaccination program.6 However, although vaccination may have an important role in controlling ILT in outbreak areas, problems may occur when vaccine is administered incorrectly, vaccination fails to provide immunity to most birds in a flock, and biosecurity measures fail to prevent spread of vaccine virus to unvaccinated flocks.3

Recombinant viruses which possess significantly higher virulence and replication capacity were found to emerge as a result of recombination between live vaccine strains (SA2 and A20), and another live vaccine strain (Serva) introduced into Australia in 2007. Interestingly, many of the ILT outbreaks occurred in vaccinated flocks. It is possible that these cases resulted from an inadequate vaccine dose or improper vaccine handling or administration.1 Replication and spread of vaccine viruses is potentiated by vaccine administration that fails to provide immunity to all the birds in a flock (e.g., via drinking water) and when biosecurity measures fail to prevent spread to unvaccinated flocks.3

JPC Diagnosis: Trachea: Tracheitis, necrotizing and lymphohistiocytic, circumferential, severe with multinucleated viral syncytia and intranuclear eosinophilic viral inclusions, Pavo cristatus, avian.

Conference Comment: Several gross differentials were discussed in the conference, including: infectious bronchitis, Newcastle disease, avian influenza, infectious coryza, and mycoplasmosis.

Infectious bronchitis (IBV), caused by a coronavirus, occurs naturally in chickens of all ages. IBV has many different serotypes and with the current vaccine there is little cross-protection between serotypes compounding that with a high mutation rate makes this disease difficult to control and diagnose. Gross lesions include upper respiratory tract infections with or without airsacculitis. Some serotypes affect the kidneys (nephrotropic strains) and can result in swollen kidneys (interstitial nephritis histologically) with uric acid crystals in renal tubules and ureters. Microscopically, the tracheitis is characterized by mucosal edema, cilia loss, degeneration and necrosis of mucosal epithelial cells, and inflammation.6

Exotic Newcastle disease (ND), caused by avian paramyxovirus-1 (APMV-1), occurs most commonly in chickens and less often in turkeys (although most poultry are susceptible) of all ages. There are three main strains of APMV-1: (1) Lentogenic strains which are mildly pathogenic strains; (2) Mesogenic strains which are moderately pathogenic; and (3) Velogenic strains which are markedly pathogenic strains. Usually, enzootic strains of ND are lentogenic or mesogenic and result in mild respiratory infections with occasional nervous signs (abnormal positions of the head and neck, AKA star gazers, paralysis, prostration). Velogenic strains cause two main pathotypes: (1) Neurotropic velogenic which cause respiratory and nervous signs with high mortality and (2) Viscerotropic velogenic which cause hemorrhagic intestinal lesions with high mortality. With velogenic strains, gross lesions can be diverse and may consist of one or more of the following: diphtheritic laryngotracheitis; conjunctival hemorrhage; air sacculitis; facial edema with hemorrhage of the comb and wattles; hemorrhages on the mucosa of the proventriculus or gizzard, Peyers patches, cecal tonsils, and large intestine; multifocal splenic necrosis; egg yolk in the abdominal cavity; and deformed eggs.6

Avian influenza (AIV) is caused by a type A influenza virus in the Orthomyxoviridae family which has two important surface antigens which help in identification and subtyping of the virus: hemagglutinin (H) which aids in viral attachment and neuraminidase (N) which cleaves sialic acid residues on host cells and mediates virion release. There are many different strains of influenza that are classified into two categories: low pathogenic (LPAI, cause little to no clinical signs) and high pathogenic (HPAI, which cause severe clinical signs and high mortality). Additionally, HPAI is subcategorized if they are highly pathogenic and notifiable strains (HPNAI). Wild reservoirs are waterfowl and shorebirds that are commonly asymptomatic and excrete the virus in their feces for many years. Once introduced into a farm, AIV is transmitted by direct and indirect contact through respiratory secretions and excrement and can be transferred from farm to farm on fomites. Gross lesions associated with LPAI outbreaks include: mild tracheitis, sinusitis, air sacculitis, and conjunctivitis and fibrinopurulent bronchopneumonia can occur with secondary bacterial infections. With HPNAI outbreaks, gross lesions are generally more severe to include: fibrinous exudates on airsacs, in the peritoneum, or pericardial sac; multifocal areas of necrosis externally on the skin, comb, and wattles or internally on the liver, kidney, spleen, or lungs, blotchy, red discoloration of the shanks, hemorrhage and petechiae on mucosal and serosal surfaces of the proventriculus and gizzard. In turkeys, encephalitis and pancreatitis have been reported as well.6

Infectious coryza, caused by Avibacterium paragallinarium, primarily affects chickens but has been rarely reported in pheasants and guinea fowl with upper respiratory tract infections often complicated by other agents like Mycoplasma gallisepticum which leads to chronic respiratory disease. Transmission of infectious coryza probably occurs through inhalation of infectious droplets or ingestion of infected feed materials. A. paragallinarium cannot exist long outside the host and is easily eliminated by disinfectants or environmental extremes. Typical gross lesions are catarrhal inflammation in the sinuses with nasal discharge, conjunctivitis with caseous exudate, edema of the face and wattles, and tracheitis, pneumonia, or air sacculitis in cases complicated by secondary pathogens.2

Mycoplasma gallisepticum is the causative agent of chronic respiratory disease in chickens and infectious sinusitis in turkeys. It is initially transmitted transovarially and can then be spread by aerosol transmission to other chicks or through contaminated feed. As with all mycoplasma infections, clinical signs take time to develop and show more profound lesions in broilers 4-8 weeks old. Gross lesions are similar to the other diseases listed above and include: catarrhal inflammation of the sinuses and upper airways, airsacculitis with hyperplastic lymphoid follicles, fibrinous perihepatitis, and adhesive pericarditis.2

Due to the similarities in gross and microscopic findings among the diseases discussed above, laboratory diagnosis (virus isolation and DNA detection) is required for definitive diagnosis.

The University of Georgia

College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Pathology

Tifton Veterinary Diagnostic & Investigational Laboratory

Tifton, GA 31793

http://www.vet.uga.edu/dlab/tifton/index.php

References:

1. Agnew-Crumpton R, Vaz PK, Devlin JM, et al. Spread of the newly emerging infectious laryngotracheitis viruses in Australia. Infect Genet Evol. 2016; 43:67-73.

2. Fulton RM. Bacterial diseases. In: Boulianne M, ed. Avian Disease Manual. 7th ed. Jacksonville, FL: American Association of Avian Pathologists, Inc.; 2013:103-108.

3. Gowthaman V, Koul M, Kumar S. Avian infectious laryngotracheitis: a neglected poultry health threat in India. Vaccine. 2016; 34:4276-4277.

4. Guy JS, Barnes HJ, Morgan LM. Virulence of infectious laryngotracheitis viruses: comparison of modified-live vaccine viruses and North Carolina field isolates. Avian Dis. 1990; 34(1):106-113.

5. Lee SW, Hartley CA, Coppo MJ, et al. Growth kinetics and transmission potential of existing and emerging field strains of infectious laryngotracheitis virus. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0120282.

6. Ojkic D, Brash ML, Jackwood MW, Shivaprasad HL. Viral diseases. In: Boulianne M, ed. Avian Disease Manual. 7th ed. Jacksonville, FL: American Association of Avian Pathologists, Inc.; 2013:52-53, 62-66.

7. Oldoni I, Rodríguez-Avila A, Riblet SM, et al. Pathogenicity and growth characteristics of selected infectious laryngotracheitis virus strains from the United States. Avian Pathol. 2009; 38(1):47-53.

8. Pitesky M, Chin RP, Carnaccini S, et al. Spatial and temporal epidemiology of infectious laryngotracheitis in central California: 20002012. Avian Diseases. 2014; 58 (4):558-565.

9. Shan-Chia Ou, Giambrone JJ. Infectious laryngotracheitis virus in chickens. World J Virol. 2012; 1(5): 142149.