Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

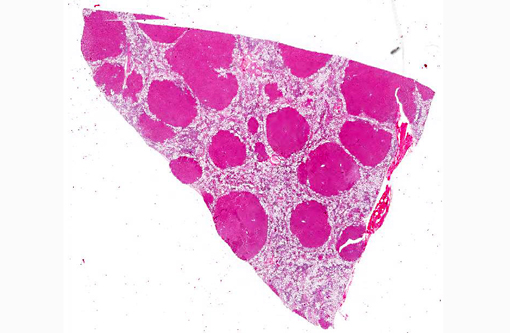

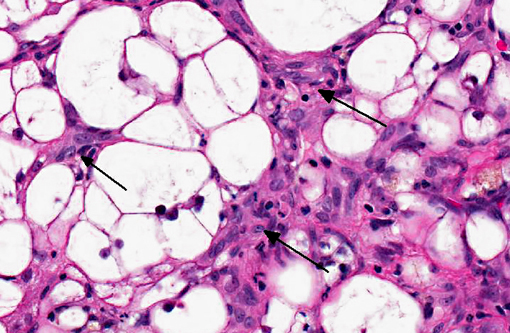

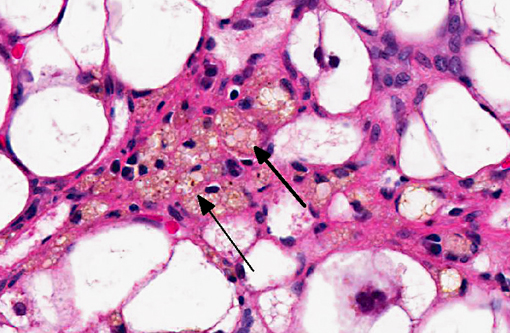

The liver sections show extensive, interconnecting areas of parenchymal collapse and hepatocellular vacuolation, usually surrounding and isolating variably sized nodules of hepatocytes (nodular regeneration). The vacuolated hepatocytes are often markedly enlarged with large amounts of clear to occasionally granular cytoplasm and peripheralized dense nuclei. The areas of vacuolar change also contain multifocal clusters of bile ducts and scant bundles of fibrous tissue. Small collections of band and segmented neutrophils (consistent with extramedullary myelopoiesis) and small numbers of plasma cells and lipid-laden macrophages infiltrate the portal spaces in these areas. Small aggregates of pigment (ceroid and/or iron)-laden macrophages are often seen within the nodules of parenchymal cells (pigment granulomas); scant neutrophils and plasma cells also infiltrate these nodules.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

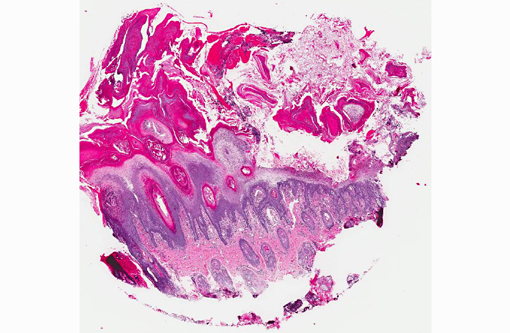

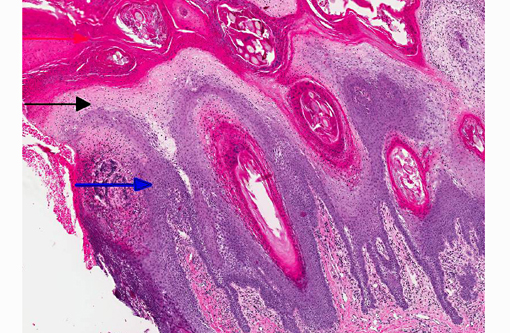

1. Haired skin, bilateral, metatarsal areas: Laminar epidermal edema, degeneration and necrosis, severe, with marked basal cell hyperplasia, parakeratotic hyperkeratosis (ie. superficial necrolytic dermatitis), and pustules/neutrophilic crusts containing bacterial colonies and budding yeast (Malassezia sp.).

2. Liver: Hepatocellular vacuolar change (vacuolar hepatopathy), severe, diffuse, with parenchymal collapse, moderate bile duct proliferation and nodular regeneration.

Lab Results:

| Parameter | Value | Reference Interval |

| Albumin | 23 G/L | 24-55 |

| ALP | 1632 U/L | 20-150 |

| ALT | 442 U/L | 10-118 |

| Glucose | 9.2 mmol/L | 3.3-6.1 |

| WBC | 19.1 x 103/mm3 | 6.0-17.0 |

| segmented | 94% | |

| lymphocytes | 3% | |

| monocytes | 2% | |

| bands | 1% | |

| RBC | 4.12 x 106/mm3 | 5.50-8.50 |

| urine glucose | 3+ |

Liver cytology performed approximately one week before euthanasia revealed cholestasis, low numbers of attenuated and rarefied hepatocytes and possible neutrophilic inflammation.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Hepatocutaneous syndrome is a rare necrotizing skin disorder of dogs that is most often associated with metabolic hepatic disease (often idiopathic vacuolar hepatopathy),(2,8) although it has also been described in diabetes mellitus, glucagon-secreting tumors (glucagonomas)(2-4,9) and prolonged phenobarbital administration.(5) It is thought that hepatic dysfunction may result in hypoaminoacidema, preventing essential amino acids from reaching the skin, leading to nutritional deprivation and subsequent necrosis. The proposed pathogenesis involves increased hepatic catabolism of amino acids (from increased gluconeogenesis),(2,7) elevated glucagon levels (due to decreased hepatic metabolism or glucagonsecreting tumors), or disturbance of zinc metabolism (possibly a result of malabsorption).(4,9) A report of superficial necrolytic dermatitis (SND) in dogs receiving phenobarbital suggested that drug induction of hepatic microsomal enzymes may result in excessive utilization of amino acids by the liver leading to deficiency.(5)

Affected animals typically develop alopecia, erythema, crusting, exudation, and ulceration of the skin. The lesions are generally distributed over the ventral aspect of the abdomen, mucocutaneous junctions, ears, periorbital region, and distal portions of the extremities. Probably the most common clinical dermatologic lesion is hyperkeratosis and deep fissuring of the footpads. Secondary skin infections with bacteria, yeasts, and dermatophytes are common. Pruritus and signs of pain are often apparent.(2-4,9) Anorexia, weight loss and lethargy may also be present.(3,4,9) Circulating liver enzyme activities are frequently high and plasma amino acid concentrations are severely low.(2,7) Results of a study of 36 dogs with histologically confirmed SND indicated that older small-breed dogs (including Shetland Sheepdogs) were primarily affected. The median age was 10 years, and 27 (75%) dogs were male.(7) Superficial necrolytic dermatitis has also been reported in cats(4) and captive black rhinoceroses.(6)

In skin sections, the histopathologic finding of parakeratosis with crusting, hydropic degeneration of keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum, and hyperplasia of the basal cell layer, imparts the characteristic red, white, and blue appearance (referred to by some as the French flag) that is diagnostic for the disease.(2) Livers of dogs with hepatocutaneous syndrome are grossly nodular. Histologically, there is severe vacuolation of hepatocytes, with parenchymal collapse and condensation of the reticulin fiber network accompanied by nodular regeneration.(8) This combination of liver features has been confused with hepatic cirrhosis by many authors. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the liver of affected dogs reveals an almost pathognomonic honeycomb pattern or Swiss cheese-like appearance consisting of a hyperechoic network surrounding hypoechoic areas of parenchyma.(2,3) The underlying cause of these hepatic changes is often undetermined; however, they have been suggested to support an underlying metabolic, hormonal, or toxic cause.(3) The cause for the hepatopathy in this dog was not determined.

Hepatocutaneous syndrome in dogs often has a poor prognosis, and survival times are often less than one year. Treatment generally includes parenteral and oral administration of amino acids, zinc, and essential fatty acids.(7) If the disease is caused by a glucagon-secreting pancreatic neoplasm, surgical removal of the neoplasm can lead to resolution of skin lesions.(2)

Differential diagnosis for canine SND includes other parakeratotic diseases such as zinc-responsive dermatosis and generic dog food-associated dermatosis. Clinical differential diagnoses include chronic erythema multiforme of older dogs, drug eruption, pemphigus foliaceous and systemic lupus erythematosus. Most of these can be ruled out by appropriate clinical history, physical examination, clinical laboratory, and histopathologic findings.(2)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Hepatocellular vacuolar degeneration, diffuse, marked with hepatocellular loss, nodular regeneration and ductular reaction.

2. Haired skin: Epidermal edema, degeneration, and necrosis, superficial, diffuse, marked, with basal cell hyperplasia, parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, and subacute dermatitis.

Conference Comment:

The distinctive gross and histological appearance of nodular regeneration occurs as a result of its contrast with adjacent expanses of parenchymal atrophy and loss, which typically occur due to reduced blood flow and bile drainage. Macro/micronodular hepatic regeneration is classically associated with cirrhosis, where bridging fibrosis is also a characteristic lesion; however, the liver in this case is striking in its relative lack of fibrosis. Instead, foci of regeneration are bound by extensive areas of parenchymal collapse, hepatocellular vacuolation and bile ductular proliferation, which is a consistent finding in superficial necrolytic dermatitis.(9)

Participants further noted the prominent hepatocellular vacuolar degeneration within submitted sections of liver, which prompted a focused exploration of the distinction between hydropic, glycogen and lipid-type vacuolar degeneration. Hydropic degeneration often follows hypoxic incidents, toxic/metabolic insults or cholestasis, while intracellular accumulation of lipid is a response to physiologic or pathologic increases in lipid mobilization or derangements in lipid metabolism. Hepatocellular glycogen accumulation, otherwise known as steroid-induced hepatopathy or hepatic glycogenosis, is typically induced by exogenous or endogenous corticosteroids. Histologically, lipid-type vacuolar degeneration produces hepatocytes with discrete globules which may coalesce into a single large vacuole that peripheralizes the nucleus, while glycogen or hydropic-type vacuolar degeneration causes significant cell swelling with indistinct vacuolar boundaries and fine, feathery cytoplasm. In severe cases of glycogenosis, nuclei and organelles may be displaced to the periphery of the cell, which complicates differentiation from lipid-vacuoles.(9) In this situation, histochemical stains may be helpful; glycogen stains strongly with PAS, while lipid stains with oil-red-O.

References:

2. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 2nd ed. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing; 2005:86-91.

3. Jacobson LS, Kirberger RM, Nesbit JW. Hepatic ultrasonography and pathological findings in dogs with hepatocutaneous syndrome: new concepts. J Vet Intern Med. 1995;9(6):399-404.

4. Kimmel SE, Christiansen W, Byrne KP. Clinicopathological, ultrasonographic, and histopathologic findings of superficial necrolytic dermatitis with hepatopathy in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2003;39:23-27.

5. March PA, Hillier A, Weisbrode SE, Mattoon JS, Johnson SE, DiBartola SP, et al. Superficial necrolytic dermatitis in 11 dogs with history of phenobarbital administration (1995-2002). J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:65-74.

6. Munson L, Koehler JW, Wilkinson JE, Miller RE. Vesicular and ulcerative dermatopathy resembling superficial necrolytic dermatitis in captive black rhinoceroses (Diceros bicornis). Vet Pathol. 1998;35:31-42.

7. Outerbridge CA, Marks SL, Rogers QR. Plasma amino acid concentrations in 36 dogs with histologically confirmed superficial necrolytic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2002;13:177-186.

8. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Limited; 2007:297-388.

9. Turek MM. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes in dogs and cats: a review of the literature. Vet Dermatol. 2003;14(6):279-296.

10. Wanless IR, Huang WY. Vascular disorders. In: Burt AD, Portmann BC, Ferrell LD, eds. MacSweens Pathology of the Liver. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012:627-629.