Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 24

29 April, 2020

CASE I: S62/16 (JPC 4084944). Tissue from a horse (Equus caballus).

Signalment: Horse, pony, adult.

History: Incidental finding during scheduled euthanasia of several ponies in the course of a parasitological study.

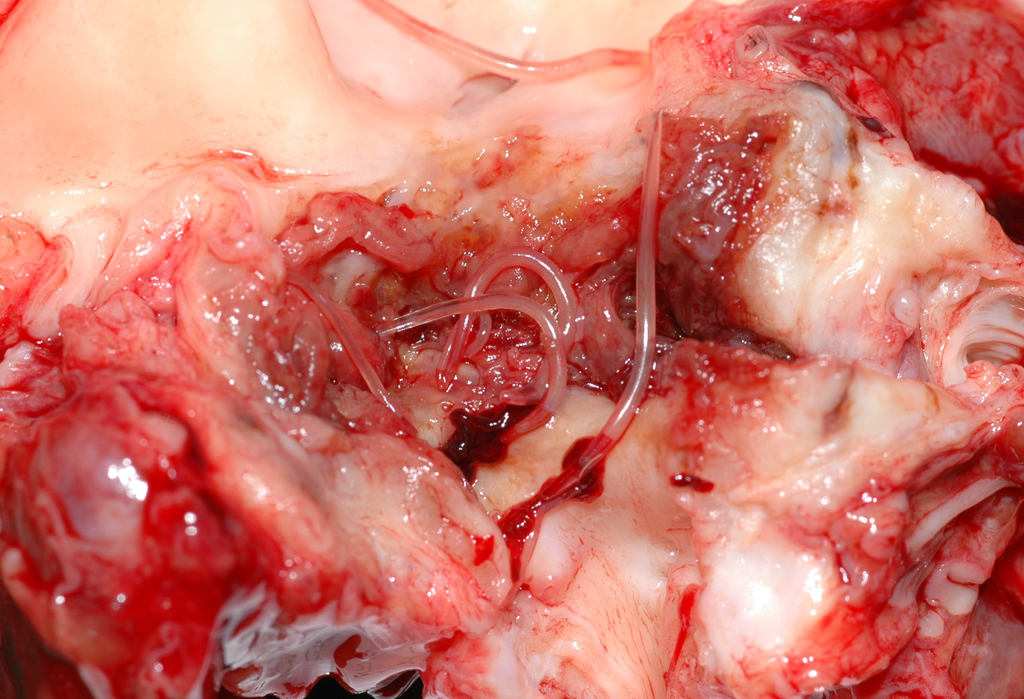

Gross Pathology: Mesenteric arteries of several ponies were thickened and stiffened. After opening of the vessels luminal larval nematodes were present in some animals. On cross sections the vessel lumina were narrowed and filled by thrombi with numerous entrapped grayish to white or transparent nematode larvae of approximately 1 to 2 cm in length and 1 mm in thickness.

Laboratory results: None.

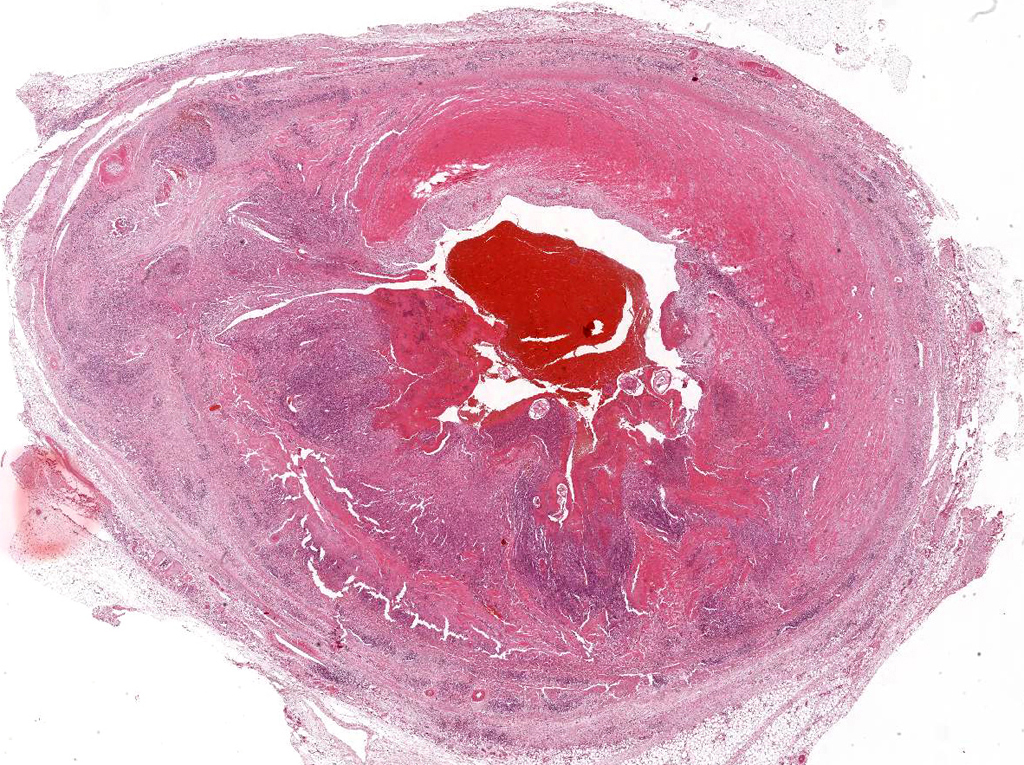

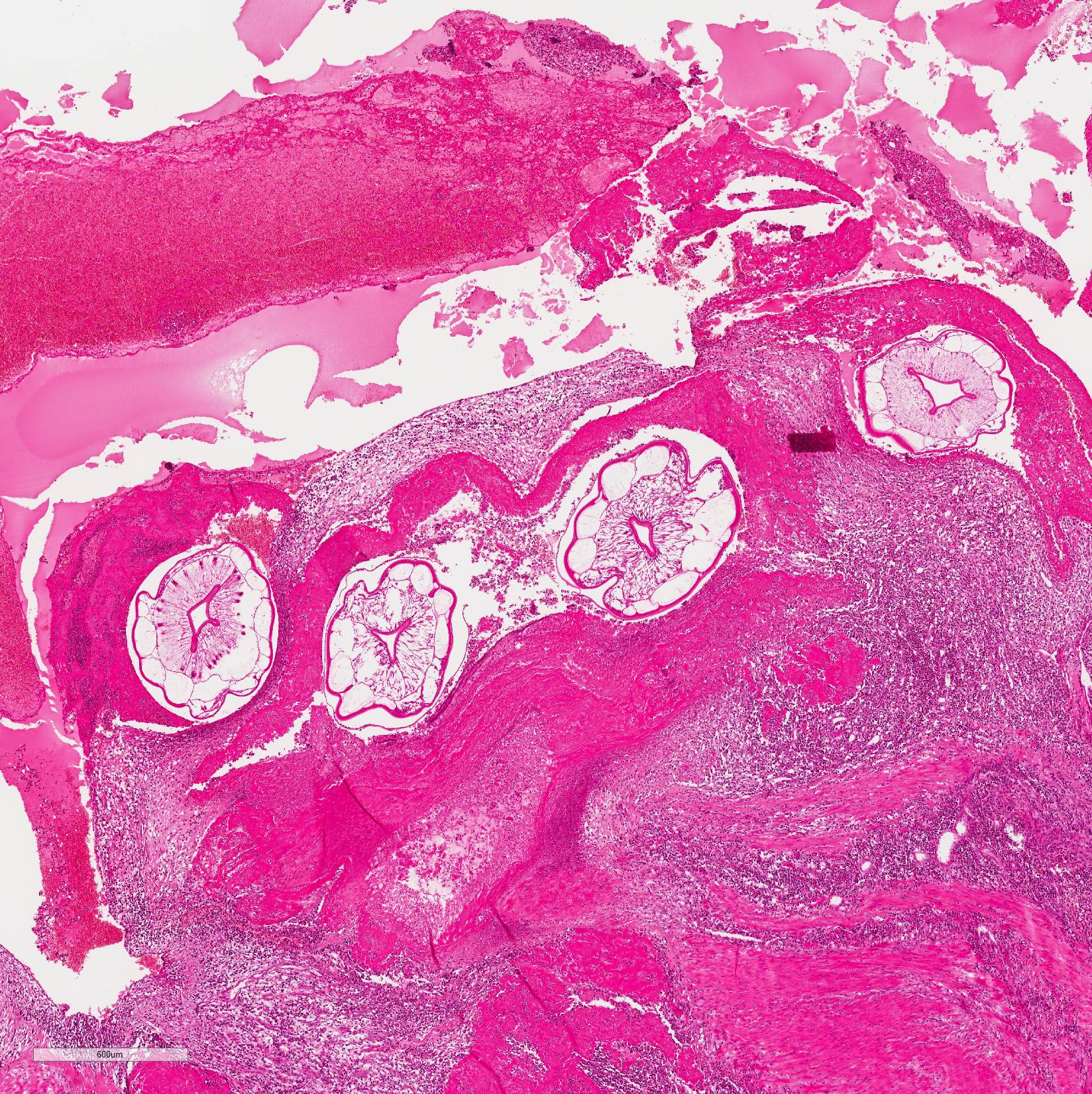

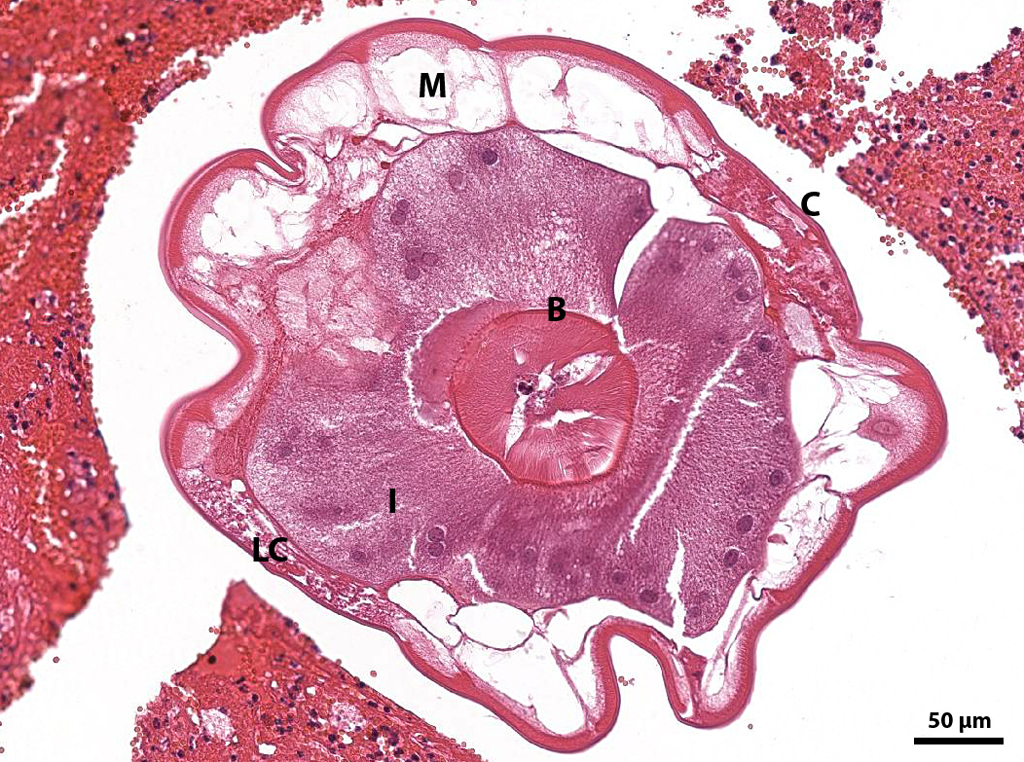

Microscopic Description: Mesenteric artery: The endothelium, tunicae interna and media are widely replaced and expanded by abundant granulation tissue and massive inflammatory infiltrate. The infiltrate is composed of mainly macrophages, viable and degenerate neutrophils, eosinophils and few lymphocytes. Numerous thin walled small caliber blood vessels, lined by plump endothelial cells and oriented perpendicular to the vascular lumen as well as increased numbers of mostly circular arranged fibroblasts and fibrocytes delineate the inflammation in the periphery. The arterial lumen is partially occluded by an eosinophilic, amorphous material (fibrin thrombus) containing alternating layers of erythrocytes, viable and degenerate neutrophils, and fibrin (lines of zahn) with multiple cross sections of nematode larvae. Larvae are up to 250 µm in diameter with a smooth cuticle, a pseudocoelom, platymyarian-meromyarian muscles, prominent lateral cords, and a large central intestine, lined by few multinucleated cells with a prominent brush border.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Mesenteric artery: arteritis, severe, chronic-active, segmental, granulomatous and eosinophilic with (white) thrombus-formation and intralesional larval nematodes consistent with Strongylus vulgaris

Contributor Comment: Virtually all horses are affected by strongylid infections, of which the most damaging to the host is the infection with the large strongyle Strongylus vulgaris4. Infectious 3rd larvae of S. vulgaris are ingested and exsheath in the small intestine. After penetrating the intestinal mucosa they molt to the 4th stage of 1 mm length and migrate in or along the intima to the cranial mesenteric artery. These larvae can cause large subserosal haemorrhages called hemomelasma ilei. After a maturation period of 3 to 4 months the 10 to 18 mm long 5th larvae (immature adult) returns to the wall of the cecum or colon via arterial lumen and encapsulate in the subserosa forming 5 to 8 mm large nodules. After rupture of the nodules with release into the intestinal lumen and another 1 to 2 months of maturation the adult nematodes produce eggs that are shed with the faeces and develop outside the horse to the 3rd larvae.6,7

The two other common large strongyles affecting horses are S. edentatus and S. equinus. S. edentatus travels via the portal system to the liver, molts to the 4th stage and re-enters the cecum via the hepatic ligaments. S. equinus molts in the walls of the ileum, caecum and colon, travels via the peritoneal cavity to the liver and later also the pancreas, molts to the 5th stage and return into the cecal lumen probably by direct penetration.7

Gross lesions can range from small visible tracts to thrombotic lesions as in this case. Thrombembolic intestinal infarction, especially of the large bowel and the colon can be the consequence.7 Chronic infections may lead to thickening or even scarring of the affected vessels. Another possible consequence is weakening of the vessel walls with subsequent aneurysm-formation and rupture.6 Debilitating disease with pyrexia, anorexia, depression, diarrhea and colic are more common in foals with high larval burden and consequence to toxic products from decaying larvae. A degree of host resistance can be slowly acquired under natural conditions, but all ages remain susceptible.6 In addition to the aortic-iliac thrombosis S. vulgaris may also cause cerebrospinal nematodiasis.7

The number of infections decreased with improvement of anthelmintics but increase again due to upcoming resistances, especially in cases of infestation with small strongyles (cyathostominosis).5 That?s why the European Union made anthelmintics available on prescription-only basis1. This in turn led to an increased need of intra vitam diagnosis of nematosis. Especially the ?traditional? egg count methods may be misleading as studies indicated that horses with counts below 100 eggs per gram can harbor cyathostomes burdens in the order of 100,000 luminal worms.4 However until now no reliable alternative method has been found.1,5,6 That?s why the number of strongylid infections seen in necropsy will possibly increase in near future.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Pathology, Freie Universitaet Berlin

http://www.vetmed.fu-berlin.de/en/einrichtungen/institute/we12/index.html

JPC Diagnosis: Mesenteric artery: Arteritis, granulomatous and eosinophilic, transmural chronic, diffuse, severe, with thrombosis and luminal larval strongyles.

JPC Comment: Even with

the widespread use of ivermectin among horse owners, the classic lesion of Strongylus

vulgaris have turned up in the WSC twice in the last 6 years (WSC 2013-2014

Conference 24 Case 4, and WSC 2017-2018 Conference 21 Case 4, 2017-2018.)

Before the widespread use of ivermectin, up to 90% of equine colic was

attributed to strongyle infection (as 90% of horses with colic without obvious

signs of obstruction had lesions associated with infection.

Arterial infarctions of the colon in animals with S. vulgaris infections have been well-documented in association with S. vulgaris infection and a source of puzzlement for veterinarians for many years. The lesion occurs in a small number of animals with remodeled mesenteric arteries, while the vast majority of infected do not show evidence of infarction. Several theories have been put forth about their cause, but none proven. It is compelling to think that pieces of the large thrombus in mesenteric arteries might break off and embolize to the affected regions, but it occurrence has never been documented. Another theory is vasospasm of the colonic arteries due to vasoactive substances liberated by the larvae or components of the thrombus (similar to the enhancement of ischemia induced in human myocardial infarcts by the thromboxane liberated by platelets.) Yet another theory is that the thickened arterial walls place pressure on the autonomic plexi, interfering with gut innervation.7

As mentioned by the contributor, reliable antemortem diagnosis of S. vulgaris infection is a continuing problem. Within the last few years, several potential antemortem diagnostic techniques have been proposed. Real-time identification of S. vulgaris antigens in fecal samples have been shown to be more effective in identifying infected animals than larval isolation techniques.3 Recently an ELISA test measuring antibodies to recombinant S. vulgaris SXP protein was shown to be 73.3% sensitive and 81.1% specific for S. vulgaris infection.2

References:

1. Andersen UV, Howe DK, Olsen SN, Nielsen MK: Recent advances in diagnosing pathogenic equine gastrointestinal helminths: the challenge of prepatent detection. Vet Parasitol 2013; 192: 1-9.

2. Anderson UV, Howe DK, Dangoudoubiyam S, Toft N, Reinemeyer CR, Lyons ET, Olsen SN, Monrad J, Nejsum P, Nielsen MK. SvSXP: a Strongylus vulgaris antigen with potential for prepatent diagnosis. Parasit Vect 2013; 6:84.

3. Kaspra A, Pfister K, Nielsen MK, Silaghi C, Fink H, Scheuerle MC. Detection of Strongylus vulgaris in quine faecal samples by real-time PCR and larval culture - method comparison and occurrence assessment. BMC Vet Res 2017; 13:19, doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0918-y.

4. Nielsen MK, Baptiste KE, Tolliver SC, Collins SS, Lyons ET: Analysis of multiyear studies in horses in Kentucky to ascertain whether counts of eggs and larvae per gram of feces are reliable indicators of numbers of strongyles and ascarids present. Vet Parasitol 2010; 174: 77-84.

5. Nielsen MK, Pfister K, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G: Selective therapy in equine parasite control--application and limitations. Vet Parasito 2014; l 202: 95-103.

6. Robinson WF, Robinson NA: Cardiovascular System. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals: Sixth Edition, pp. 1-101.e101. 2015

7. Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM: Alimentary System. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals: Sixth Edition, pp. 1-257.e252. 2015.

8. White NA: Thromboembolic colic in horses. Comp Contin Educ 1985; 7: S156-S163.