Signalment:

Gross Description:

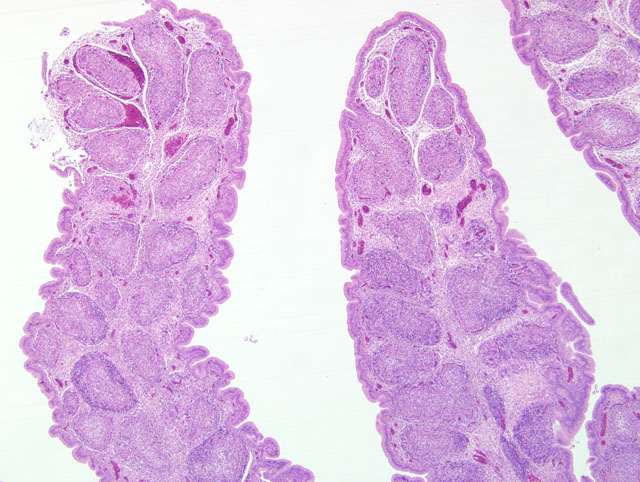

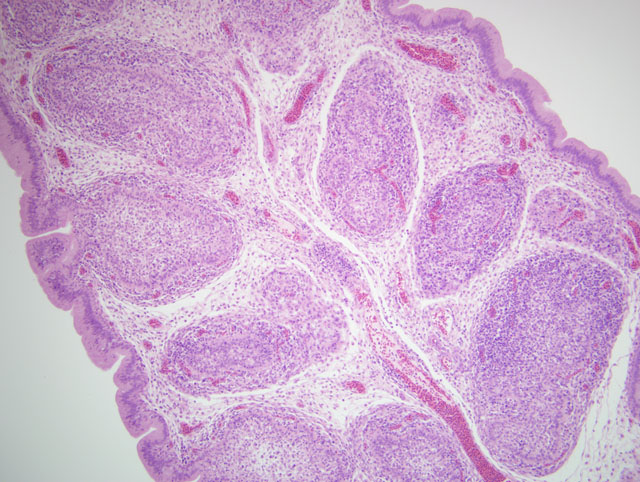

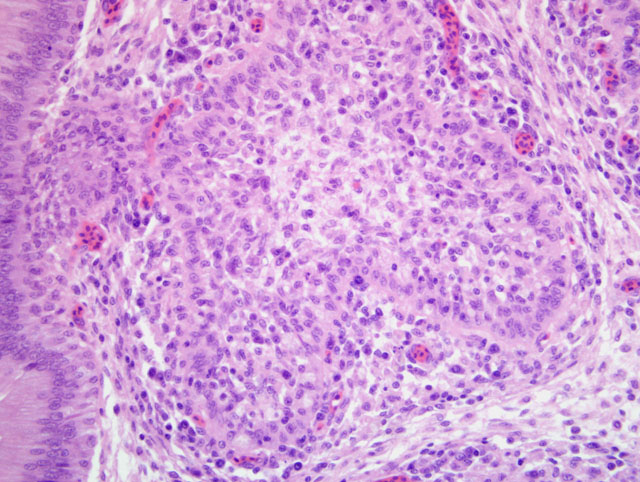

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

There are two serotypes: type 1 and type 2. The type 1 serotype is further divided into the standard (or classic) strain and variant strains. In Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America highly pathogenic serotype 1 strains have been identified and are termed very virulent infectious bursal disease (vvIBD).(2) Experimental inoculation elicits different responses depending on the strain of virus. Both the very virulent and classic strains induce typical clinical signs and gross lesions with mortality rates of 10-50% for classical strains and up to 50-100% during infections with vvIBDV.(2) Variant strains such as the type E strain used to infect this chicken typically cause bursal lesions to develop but rarely induce acute clinical signs or mortality.(5) In general, serotype 2 virus is not pathogenic and does not protect against challenge with serotype 1 viruses.(2)

Grossly the bursa initially increases in size due to edema and hyperemia, but then begins to atrophy due to lymphoid depletion and eventually decreases in size to one-third of its original weight.(1) The bursa may have necrotic foci with mild to extensive hemorrhage and the spleen may be mildly enlarged with uniform small gray foci on the surface.(2) Hemorrhages of the thigh and pectoral muscles are frequently present and severely dehydrated chickens commonly develop non-specific renal lesions.(2)

Microscopically the cloacal bursa is the most severely affected organ, but other lymphatic tissues, such as the spleen, thymus, and Harderian gland, have similar but milder lesions than the bursa.(3) Initially there is degeneration and necrosis of lymphocytes in the bursal medulla as early as 36 hours after infection.(1) As the disease progresses, heterophils, macrophages, and eventually fibroblasts accumulate in the follicular and interfollicular areas. In the spleen there may be hyperplasia of splenic reticuloendothelial cells along with lymphoid necrosis and the Harderian gland can have areas of necrosis.(1,3)

Multiple virus and host variables, including strain of virus, age and breed of chicken, and maternal immunity and vaccine status affect the development of infection/disease.(4) The pathogenesis of oral infection results in an initial viremia within five hours and a second massive viremia may occur following infection of the bursa.(2) The virus targets immature dividing B lymphocytes resulting in necrosis and apoptosis of B cells with activation of macrophages, T cells, and NK cells.(2,4) Recovery from complete immunosuppression can occur if large follicles capable of replenishing the B cell population are reconstituted from endogenous stem cells that survived the initial infection.(2,9) The long-term effect of IBD is frequently immunosuppression due to decreased humoral immunity, and to a much lesser degree, cellular immunity resulting in increased susceptibility to disease and poor immune response to vaccination.(7)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Based on the histomorphologic findings of lymphoid necrosis and depletion, conference participants were evenly divided between infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) and chicken anemia virus (CAV) (Circoviridae, Gyrovirus) as the underlying etiology. Chicken anemia virus infects hemocytoblasts in the bone marrow and lymphoblasts in the cortex of the thymus, resulting in anemia with a hematocrit of 6-27% and pancytopenia. Gross lesions of CAV include thymic atrophy; bone marrow atrophy; hemorrhage in the proventricular mucosa, subcutaneous tissue, and skeletal muscle; and, less commonly, bursal atrophy. Panmyelophthisis and generalized lymphoid atrophy are commonly observed in chickens infected with CAV, with the thymus exhibiting the most severe lesions. When present, bursal lesions caused by CAV are less severe than those induced by IBDV, and include lymphofollicular atropy, few areas of necrosis, and infolding of the epithelium with hydropic degeneration and proliferation of reticular cells. In contrast, infection with IBDV frequently results in marked to severe lymphofollicular bursal atrophy, hemorrhage, edema, heterophilic inflammation, and hyperplasia of the bursal epithelium, sometimes resulting in a pseudoglandular appearance.(2,6)

The contributor discusses immunosuppression and decreased humoral immunity caused by IBDV infection, which renders infected chicks more susceptible to disease. Immunosuppression is most severe in chicks exposed to the virus within 2-3 weeks of hatch, and manifests clinically as impaired protective response to vaccination, increased incidence of secondary infections, poor feed conversion, and increased rates of carcass condemnation at processing. Interestingly, although T lymphocytes are resistant to infection with IBDV, the virus does cause thymic atrophy, thymocyte apoptosis, and impaired cell-mediated immunity, in addition to the expected impairment of humoral immunity that results from depletion of IgM+ B lymphocytes in the cloacal bursa, spleen, and cecal tonsils. Infection with IBDV is also thought to impair innate immunity, compromising the phagocytic activity of macrophages.(7) The Harderian gland is a component of the local immune system of the upper respiratory tract, and its function is also impaired by IBDV infection.(2)

The United States was considered free of the very velogenic (vvIBD) form of the disease; however, an outbreak of vvIBD was recently reported in 2009.(8) The source of the most recent disease outbreak has not been determined. Field veterinarians and diagnosticians should be aware of this report and consider vvIBD in the differential diagnosis when clinical signs, epidemiologic evidence, and diagnostic data indicate it as a potential etiology.

References:

2. Eterradossi N, Saif YM: Infectious bursal disease. In: Diseases of Poultry, ed. Saif YM, 12th ed., pp. 185-208. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA, 2008

3. Ley DH, Yamamoto R, Bickford AA: The pathogenesis of infectious bursal disease: serologic, histopathologic, and clinical chemical observations. Avian Dis 27:1060-1085, 1983

4. M+�-+ller H, Islam MR, Raue R: Research on infectious bursal disease-the past, the present and the future. Vet Microbiol 97:153-165, 2003

5. Rodriguez-Chavez IR, Rosenberger JK, Cloud SS, Pope CR: Characterization of the antigenic, immunogenic, and pathogenic variation of infectious bursal disease virus due to propagation in different host systems (bursa, embryo, and cell culture). III. Pathogenicity. Avian Pathol 31:485 - 492, 2002

6. Schat KA, van Santen VL: Chicken infectious anemia. In: Diseases of Poultry, ed. Saif YM, 12th ed., pp. 211-249. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA, 2008

7. Sharma JM, Kim I-J, Rautenschlein S, Yeh H-Y: Infectious bursal disease virus of chickens: pathogenesis and immunosuppression. Dev Comp Immunol 24:223-235, 2000

8. Stoute ST, Jackwood DJ, Sommer-Wagner SE, Cooper GL, Anderson ML, Woolcock PR, BickfordAA, Senties- Cue CG, Charlton BR: The diagnosis of very virulent infectious bursal disease in California pullets 53:321-326, 2009

9. Withers DR, Young JR, Davison TF: Infectious bursal disease virus-induced immunosuppression in the chick is associated with the presence of undifferentiated follicles in the recovering bursa. Viral Immunol 18:127-137, 2005