Signalment:

Gross Description:

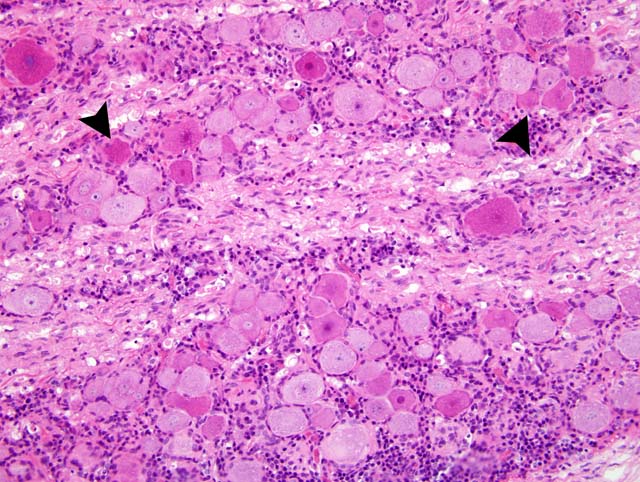

Histopathologic Description:

Immunohistochemically, PTV antigens were detected in the cytoplasm of large nerve cells and glial cells in the cerebellar nuclei, the gray matter of the brain stem, and the ventral horn of the spinal cord of all examined pigs. In the spinal ganglia, PTV antigen was strongly detected in the cytoplasm of ganglion cells. In the nervous system, the distribution of PTV antigen was consistent with the lesion distribution. In the lesion, no antigens were seen in the central severe area. Antigens were mainly seen in the periphery of the severe lesions and, especially, in minimal to mild lesions around areas of perivascular cuffing.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Dorsal root ganglia: nonsuppurative, ganglionitis

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In the present cases, the morbidity and mortality were low and the characteristic clinical signs were flaccid paralysis of the hind limbs. The nonsuppurative lesions were distributed mainly in the gray matter of the brainstem and the spinal cord. These clinical and histological features of the present disease are similar to those of the disease produced by less virulent PTV strains, especially those of Talfan disease.(3,4) In previous reports of experimental Talfan disease, axonal degeneration was seen in the ventral root and sciatic nerves.(1) In the white matter of the spinal cord, slight degenerative changes were seen only in the dorsal funiculus.(1) In contrast, demyelination and axonal degeneration in the present cases, which resulted from a natural outbreak in Japan, appeared in the whole white matter, and in either the ventral or dorsal root.

Immunohistochemically, anti-PTV monoclonal antibody (no.9, IgM) (National Institute of Animal Health, Japan) 6 was used as the primary antibody. PTV antigens were detected in cytoplasm of nerve cells, glial cells and endothelial cells in the cerebellar nuclei, the gray matter of the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata and the ventral horn of the spinal cord and of ganglion cells in the spinal ganglion corresponding to those lesions characterized as nonsuppurative encephalomyelitis and ganglionitis in the pigs. The results suggest that nerve cells of the brainstem and spinal cord, and ganglion cells of the spinal ganglion permit PTV replication and represent the main target cell population of PTV.

The isolation of PTV from CNS is important for diagnosing enterovirus encephalomyelitis.(1) However, it has been reported that isolation of virus from CNS is quite difficult, and virus isolation is not always possible using routine techniques in the cases of enterovirus encephalomyelitis of pigs.(4) The optimum conditions for virus isolation from CNS, including the relationship of clinical signs to the presence of infectious virus and anatomic site where the virus is present in high density, have not been clarified in this disease. In the present cases, PTV was isolated from cerebellum and/or brainstem in the pigs slaughtered about three weeks after the onset of neural signs, but not from the cerebrum. These results suggest that sampling for virus isolation should be from the cerebellum or brainstem for the successful diagnoses enterovirus encephalomyelitis.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Conference participants discussed other viruses affecting the nervous system of pigs. Pseudorabies (suid herpesvirus 1) causes nonsuppurative encephalitis primarily affecting the gray matter, neuronal necrosis and ganglioneuritis in the paravertebral ganglia.(7) Eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies are present in the neurons and astroglia. Lesions are most severe in the cerebral cortex (differentiating it from porcine teschovirus), brain stem, spinal ganglia and basal ganglia.(7) Very young and aborted pigs typically have small areas of necrosis with eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions in the liver, tonsils, lung, spleen, placenta and adrenal glands.(7) Porcine hemagglutinating encephalitis virus (HEV) is a coronavirus that causes two clinical syndromes in young pigs: neurological signs occur in 4-7-day-old piglets and vomiting and wasting disease occurs in 4-14-day-old piglets.(7) Neurological lesions include nonsuppurative encephalomyelitis affecting the gray matter of the medulla and brain stem, and inflammation within the trigeminal, paravertebral and autonomic ganglia, and the gastric myenteric plexus.(7) Classical swine fever (porcine pestivirus) causes vascular lesions that result in hemorrhage, infarction, necrosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation.(6) Common lesions include hemorrhages in various organs (especially the lymph nodes), renal petechiae and splenic infarction.(6) Neural lesions occur in the gray and white matter, and primarily affect the medulla oblongata, pons, colliculi and thalamus.(10) There is endothelial swelling, proliferation and necrosis; perivascular lymphocytic cuffing; hemorrhage and thrombosis; gliosis; and neuronal degeneration.(10) In utero infections result in cerebellar hypoplasia and spinal cord hypomyelinoogenesis.(7) Two paramyxoviral diseases of pigs include porcine rubulavirus encephalomyelitis (Blue eye disease) and Nipah virus. Porcine rubulavirus causes encephalomyelitis, reproductive failure and corneal opacity primarily in Mexico. There is nonsuppurative polioencephalomyelitis affecting the thalamus, midbrain and cortex. Additional lesions include anterior uveitis, corneal edema, epididymitis, orchitis and interstitial pneumonia.(7) Nipah encephalitis is an emerging disease causing severe and rapidly progressive encephalitis and pneumonia in pigs, other animals and humans.(7) Fruit bats are the natural reservoir. There is necrotizing vasculitis and fibrinoid necrosis of arterioles, venules and capillaries with endothelial syncytial cells resulting in large areas of hemorrhage and infarction. Eosinophilic intracytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusions are occasionally found in neurons and endothelial syncytia. Blood vessels in the lung, brain, glomeruli and lymphoid organs are most commonly affected.(7) Additional lesions include bronchointerstitial pneumonia with necrotizing bronchiolitis, lymphocytic and neutrophilic meningitis, nonsuppurative encephalitis and gliosis.(7)

References:

2. Harding JDJ, Done JT, Kershaw GF: A transmissible polio-encephalomyelitis of pigs (Talfan disease). Vet Rec 69:824-832, 1957

3. Jubb KVF, Huxtable CR: The nervous system. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, eds. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC and Palmer N, 4th ed., vol. 1, pp. 267-439. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 1993

4. La Rosa G, Muscillo M, Di Grazia A, Fontana S, Iaconelli M, Tollis M: Validation of RT-PCR assays for molecular characterization of porcine teschoviruses and enteroviruses. J Vet Med B 53:257-265, 2007

5. M+�-�dr V: Enterovirus encephalomyelitis (previously Teschen/Talfan disease). In: Manual of standards for diagnostic tests and vaccines, 4th ed., pp. 630-637. Office International des Epizooties, Paris, 2000

6. Maxie MG, Robinson WF: Cardiovascular system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 3, pp. 78-82. Saunders Elsevier, London, UK, 2007

7. Maxie MG, Youssef S: Nervous system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 321-433. Saunders Elsevier, London, UK, 2007

8. Yamada M, Kaku Y, Nakamura K, Yoshii M, Yamamoto Y, Miyazaki A, Tsunemitsu H, Narita M: Immunohistochemical detection of porcine teschovirus antigen in the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens from pigs experimentally infected with porcine teschovirus. J Vet Med A 54:571-574, 2007

9. Yamada M, et al. Al.: Immunohistochemical distribution of viral antigens in pigs naturally infected with porcine teschovirus. J Vet Med Sci 70:305-308, 2008

10. Zachary JF: Nervous system. In: Pathological Basis of Veterinary Disease, eds. McGavin MD, Zachary JF, 4th ed., p. 967. Mosby Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2007